Developing a Model to Measure Business Performance for Private Business Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accredited Business Schools in South Africa Offering MBA Degrees: 2020

Accredited Business Schools in South Africa offering MBA Degrees: 2020 PMR.africa has completed its annual national ACCREDITED BUSINESS SCHOOLS survey on Accredited Business Schools offering MBA degrees OFFERING MBA/MBL DEGREES MeaN score in South Africa. (out of A possible 10.00) Henley Business School – Africa 8.19 The respondents (employers) rated the MBA graduates and students in the workplace representing accredited Milpark Business School (MBS) 8.06 Business Schools across 20 attributes/criteria (on a scale of Graduate School of Business & Leadership (GSB&L) – 0.00 – 10.00; where 0.00 = poor, 5.00 = average and 10.00 = University of KwaZulu-Natal 8.00 outstanding), namely: Wits Business School – University of the Witwatersrand 7.95 ● Academic knowledge ● Application of knowledge in the workplace The University of Pretoria’s Gordon Institute ● Communication skills/abilities of Business Science (GIBS) 7.90 ● Emotional intelligence University of Cape Town Graduate School ● Entrepreneurial skills/capacity/abilities of Business (GSB) 7.90 ● Environmental awareness Rhodes Business School 7.87 ● Ethical business conduct ● Financial management NWU School of Business & Governance 7.84 ● Future oriented (able to make long-term decisions) University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB) 7.82 ● Human resource management ● Implementation of corporate governance Tshwane School for Business & Society (TSB) 7.72 ● Information management Regenesys Business School 7.70 ● Innovation ● Insight into sound sustainable development Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Business School 7.69 ● International perspective University of South Africa (UNISA) Graduate School ● Leadership skills/abilities of Business Leadership (SBL) – MBL 7.65 ● Marketing management ● Operational management School of Management – University of the Free State 7.60 ● Quantitative abilities/skills Turfloop Graduate School of Leadership – ● Strategic management University of Limpopo 7.50 The ratings are based on the perceptions of the respondents. -

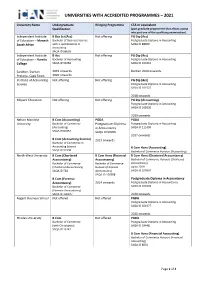

Universities with Accredited Programmes – 2021

UNIVERSITIES WITH ACCREDITED PROGRAMMES – 2021 University Name Undergraduate Bridging Programme CTA or equivalent Qualification (post graduate programme that allows access into part one of the qualifying examination) Independent Institute B Bus Sci (Acc) Not offering PG Dip (Acc) of Education – Monash Bachelor of Business Science Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting South Africa with a specialisation in SAQA ID 88609 Accounting SAQA ID 88603 Independent Institute B Acc Not offering PG Dip (Acc) of Education – Varsity Bachelor of Accounting Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting College SAQA ID 99284 SAQA ID 109416 Sandton, Durban 2019 onwards Durban 2020 onwards Pretoria, Cape Town 2020 onwards Institute of Accounting Not offering Not offering PG Dip (Acc) Science Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting SAQA ID 101527 2018 onwards Milpark Education Not offering Not offering PG Dip (Accounting) Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting SAQA ID 108930 2019 onwards Nelson Mandela B Com (Accounting) PGDA PGDA University Bachelor of Commerce Postgraduate Diploma Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting (Accounting) in Accountancy SAQA ID 115399 SAQA ID 87057 SAQA ID 90906 2017 onwards B Com (Accounting Science) 2013 onwards Bachelor of Commerce in Accounting Science B Com Hons (Accounting) SAQA ID 91998 Bachelor of Commerce Honours (Accounting) North-West University B Com (Chartered B Com Hons (Financial B Com Hons (Chartered Accountancy) Accountancy) Accountancy) Bachelor of Commerce Honours (Chartered Bachelor of Commerce Bachelor of Commerce Accountancy) (Chartered -

Access the Repository

REGENT BUSINESS SCHOOL Data Base of all Research and Research Presentations and Allied Research Activities conducted by the REGENT Business School’s Directorate of Research and Innovation for the period 2002 to December 2016: A REPOSITORY OF ALL RESEARCH CONDUCTED AND UNDERTAKEN 1. INTRODUCTION Humble beginnings by REGENT Business School in Respect to Research: Advancing the South African Research Agenda Against all Odds in a Sustained, Coordinated and Professional Manner. It is our pleasure to document all of the research and allied activities including journal articles published and, undertaken by the REGENT Business School for the period 2002 to December 2016 (A period of 14 Years). It was a difficult task to assemble the data because, this exercise was conducted for the first time and, some of the data was not easily accessible going back to the year 2002, or was not on record within the school. The initial years saw the school finding its feet and, it was a period when research was at a very rudimentary stage and level of development and engagement. i In spite of the difficulties encountered in assembling the data, it was an exercise and, effort that achieved the desired effect of obtaining the maximum data of most of the research conducted by the institution, including allied research activities, over a period of nearly two decades. It was a grueling exercise and we are happy with our efforts of creating a more than adequate data base for scrutiny by management, staff, and outside organizations and formations, including the regulatory authority in the form of the Council on Higher Education (CHE) and the Department of Higher Education. -

MBA Rankings

Global MBA Rankings MBA RANKINGS The benefits attached to an MBA qualification are significant. Career progression, networking opportunities and salary increases are just some of the reasons why application volumes have been increasing. » aving made the decision to pursue an MBA, deciding upon a school is not easy. Many factors need to be considered, including location, reputation and teaching H methods. However, preparing a shortlist of schools is perhaps the most difficult task, given the plethora of schools offering an MBA option. Therefore, in order to simplify the decision-making process, CEO Magazine has assessed the performance of MBA providers based upon certain key performance indicators: Key Performance Indicators EMERGING MARKETS MBA School ❯ FACULTY Rankings: ‘The Rising Stars’ ❯ TUITION FEES (Tier One) ❯ INTERNATIONAL REACH SOUTH AND CENTRAL AMERICA EGP University of Porto Business School ❯ INNOVATION ESAN University ENPC School of International Management ❯ DELIVERY METHODS FIA Business School EOI - Escuela de Organización Industrial ❯ CAREER PROGRESSION Florida Atlantic University Erasmus University: RSM (where possible) IAE Business School ESADE HEC Lausanne Those schools, which have been identified IESE Universidad de La Sabana HEC Paris for inclusion into the tables below, are Universidad de los Andes Henley Business School considered by the CEO Review Panel Universidad Torcuato Di Tella ICN (CRP) to be of tier-one status. Typically, University of the West Indies Cave Hill Institute for Management (IfM) these schools demonstrate a high level of IMD innovation and thought leadership; class EASTERN EUROPE INSEAD ISCTE sizes tend to be moderate, senior faculty are Aalto University of Economics ISEG used and the make up of students is diverse. -

1000 Best Business Schools EDUNIVERSAL OFFICIAL SELECTION - 1,000 BEST BUSINESS SCHOOLS YOUR RECOMMENDATIONS

2021 Eduniversal Official Selection - 1000 Best Business Schools EDUNIVERSAL OFFICIAL SELECTION - 1,000 BEST BUSINESS SCHOOLS YOUR RECOMMENDATIONS Country School Name Palm Vote Albania Universiteti I Tiranës Faculty of Economics 2 Algeria Ecole Supérieure Algérienne des Affaires - ESAA 3 Algeria ESC Alger 2 Algeria MDI Alger Business School 3 Algeria Université d'Alger - Faculté des Sciences Economiques et de Gestion 2 Angola Universidade Agostinho Neto - Faculdade de Economia 1 Argentina IAE Business School - UNIVERSIDAD AUSTRAL 4 Argentina ITBA - Instituto Tecnologico de Buenos Aires 2 Argentina Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina (UCA) - Facultad de Ciencias Economicas 4 Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa - UADE Business School 3 Argentina Universidad Católica de Córdoba - ICDA ESCUELA DE NEGOCIOS 4 Argentina Universidad de San Andrés Escuela de Administración y Negocios 3 Argentina Universidad Del Cema (UCEMA) - Departamento De Dirección De Empresas 3 Argentina Universidad Nacional de Córdoba - Facultad de Ciencias Economicas 3 Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario - Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Estadística 2 Argentina Universidad Nacional del Litoral ? Facultad de Ciencias Económicas 1 Argentina Universidad Torcuato Di Tella (UTDT) - Escuela de Negocios 3 Argentina university of buenos aires school of economic sciences 4 Armenia American University of Armenia - Manoogian Simone College of Business & Economics 2 Armenia Russian Armenian University ? Institute of Economics and Business 2 Australia Bond University -

Business Schools

Unpacking COVID-19 in an African illuminated in purple for the entire month, leading the Nadia Krige, 17 Dec 2020 NWU into a new year. Demonstrating the NWU’s ethic of care, this symbolic gesture is in remembrance of the Despite the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic has left no sacrifices that were made and challenges that were country unaffected, it is important to understand that its overcome, and the resilience and excellence displayed impacts have hardly been uniform. Professor Ralph despite the various challenges posed by the Covid-19 Hamann from the University of Cape Town Graduate pandemic. School of Business (UCT GSB) is among a group of researchers analysing the initial impacts of COVID-19 in Link: https://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/499/211327.html Africa. They recently published a paper identifying five SOUTH AFRICAN contextual features that need to be considered in ongoing Regent Business School’s rebalancing act BUSINESS SCHOOLS efforts to limit the spread of the disease and mitigate its 13 October 2020 - 10:00 David Furlonger MEDIA COVERAGE AND COMMENTARY 2020 impacts on the continent. Financial Mail Link: https://www.news.uct.ac.za/news/research-office/-article%20/2020-12-17-unpacking-covid-19-in-an-african-context Skills will be more important than paper qualifications, says Regent’s Ahmed Shaikh Regenesys Foundation pledges millions to-wards education initiative Higher education, including MBAs, will undergo a ENCA, 16 June 2020 “rebalancing” to meet the needs of a market fundamentally changed by the Covid-19 pandemic, says Regent Business The Regenesys Foundation is pledging a R100m towards a School MD Ahmed Shaikh. -

Title Initials Surname Qualification Type Qualification Name Institution

Title Initials Surname Qualification Type Qualification Name Institution Mr A Abdul Latiff Bachelor Honours Degree Accounting University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Mr CJ Abrahams Bachelor Honours Degree Education Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) Mr G Abrahams Masters Degree Law University of South Africa (UNISA) Ms W Abrahams Bachelor Honours Degree Education Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) Mr E Adam Masters Degree Commerce University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Mr BL Ah-Why Advanced Diploma Information Technology and Computer Science Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) Ms KR Aires Bachelor Honours Degree Marketing The IIE Mr PE Alvarez Masters Degree Administration Technikon Natal Dr F Amoah Doctoral Degree Marketing Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) Mrs CH Anderson General Certificate Computing Institution to be Confirmed Mrs FS Anderson Bachelor Honours Degree Accounting University of South Africa (UNISA) Mr MJ Andrew Masters Degree Business Administration De Montfort University Mrs PL Andrew Degree/ Bachelor’s Degree Education University of the Witwatersrand (WITS) Mrs C Andrews Masters Degree Business Management Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) Mrs JS Appalsami Bachelor Honours Degree Education Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) Mr M Appalsami Postgraduate Diploma Education University of South Africa (UNISA) Mr G Appiah-Baiden Bachelor Honours Degree Accounting University of the Witwatersrand (WITS) Mrs S Arbee Bachelor Honours Degree Education University of Durban-Westville -

Articulation Possibilities for Community Development Workers

2015 CENTRE FOR INTEGRATED POST SCHOOL EDUCATION AND TRAINING Ivor Baatjes and Sheri Hamilton, with Lucky Maluleke, Anthony Sibiya & Sonya Leurquain-Steyn Articulation Possibilities for Community Development Workers [A final report prepared for the South African Qualifications Authority.] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 4 Part One: Introduction and background .................................................................................................... 6 Part 2: Research design ........................................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Desktop review ........................................................................................................................8 2.2 Case study ................................................................................................................................8 2.3 Focus groups ............................................................................................................................8 2.4 Interviews ................................................................................................................................9 2.5 Limitations and constraints .......................................................................................................9 Part 3 - Literature review and data ........................................................................................................ -

Accredited Business Schools in South Africa Offering MBA Degrees: 2020

Accredited Business Schools in South Africa offering MBA Degrees: 2020 PMR.africa has completed its annual national ACCREDITED BUSINESS SCHOOLS survey on Accredited Business Schools offering MBA degrees OFFERING MBA/MBL DEGREES MeaN scoRE in South Africa. (OUT of A Possible 10.00) Henley Business School – Africa 8.19 The respondents (employers) rated the MBA graduates and students in the workplace representing accredited Milpark Business School (MBS) 8.06 Business Schools across 20 attributes/criteria (on a scale of Graduate School of Business & Leadership (GSB&L) – 0.00 – 10.00; where 0.00 = poor, 5.00 = average and 10.00 = University of KwaZulu-Natal 8.00 outstanding), namely: Wits Business School – University of the Witwatersrand 7.95 ● Academic knowledge ● Application of knowledge in the workplace The University of Pretoria’s Gordon Institute ● Communication skills/abilities of Business Science (GIBS) 7.90 ● Emotional intelligence University of Cape Town Graduate School ● Entrepreneurial skills/capacity/abilities of Business (GSB) 7.90 ● Environmental awareness Rhodes Business School 7.87 ● Ethical business conduct ● Financial management NWU School of Business & Governance 7.84 ● Future oriented (able to make long-term decisions) University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB) 7.82 ● Human resource management ● Implementation of corporate governance Tshwane School for Business & Society (TSB) 7.72 ● Information management Regenesys Business School 7.70 ● Innovation ● Insight into sound sustainable development Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Business School 7.69 ● International perspective University of South Africa (UNISA) Graduate School ● Leadership skills/abilities of Business Leadership (SBL) 7.65 ● Marketing management ● Operational management School of Management – University of the Free State 7.60 ● Quantitative abilities/skills Turfloop Graduate School of Leadership – ● Strategic management University of Limpopo 7.50 The ratings are based on the perceptions of the respondents. -

Accredited Business Schools in South Africa Offering MBA Degrees: 2016

Accredited Business Schools in South Africa offering MBA Degrees: 2016 PMR.africa has completed its annual national ACCREDITED BUSINESS SCHOOLS OFFERING survey on Accredited Business Schools offering MBA degrees MBA/MBL DEGREES Mean score in South Africa. (out of A possible 10.00) University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB) 8.22 The respondents (employers) rated the MBA graduates and Milpark Business School 8.10 students in the workplace representing accredited Business Henley Business School, Africa 8.00 Schools across 19 attributes/criteria (on a scale of 0.00 – 10.00; The University of Pretoria’s Gordon where 0.00 = poor, 5.00 = average and 10.00 = outstanding), Institute of Business Science (GIBS) 8.00 namely: Regenesys Business School 7.90 Graduate School of Business & Leadership – ● Academic knowledge University of KwaZulu-Natal 7.80 ● Application of knowledge in the workplace University of Cape Town Graduate ● Communication skills/abilities School of Business (GSB) 7.80 ● Emotional intelligence Rhodes Business School 7.72 ● Entrepreneurial skills/capacity/abilities NWU School of Business & Governance 7.65 ● Environmental awareness Wits Business School – University of the Witwatersrand 7.30 ● Ethical business conduct University of South Africa (UNISA) ● Financial management Graduate School of Business Leadership (SBL) 7.16 ● Human resource management Tshwane University of Technology Business School 7.12 ● Implementation of corporate governance Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Business School 7.00 ● Information management -

A Pilot Study of MBA Programmes in South Africa’

Muposhi, A., Dhurup, M., Martin, R.L. and Bhadury, J. (2019) ‘A pilot study of MBA programmes in South Africa’. London Review of Education, 17 (3): 406–428. DOI https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.17.3.14 A pilot study of MBA programmes in South Africa Asphat Muposhi – Midlands State University, Zimbabwe Manilall Dhurup – Vaal University of Technology, South Africa Robert L. Martin – University of Venda, South Africa Joyendu Bhadury* – Radford University, USA Abstract In recent years, Master of Business Administration (MBA) programmes and their curricula have been subjected to substantial scrutiny. However, the majority of studies have been confined to business schools in Western countries. By comparison, much less research is available on MBA programmes in developing countries, particularly those in Africa. In an effort to address this gap, this article examines MBA programmes in South Africa by first situating them within the global MBA curriculum debate. It then notes the need to move away from a generalist MBA programme to a specialized MBA in line with emerging global trends. Finally, it suggests a multidisciplinary approach to the redesign of the MBA curriculum. Keywords: Master of Business Administration, curriculum, business schools, South Africa Introduction There is general consensus that the Master of Business Administration (MBA) is the flagship degree programme in the discipline of business and management education (Blackburn, 2011; Lundstrom, 2011; Rubin and Dierdorff, 2013). While precise data about the number of MBA degrees awarded -

Qualifications Approved for Registration on the NQF on 17 February 2016 Source: National Learners' Records Database Page 1 of 2

Qualifications approved for registration on the NQF on 17 February 2016 NQF Sub- Originator Qual ID Qualification Title NQF Level Min Registration Registration Framework Credits Status End Date HEQSF Durban University of Technology 97709 Diploma in Information and Communications Technology in Business NQF Level 06 360 Registered 17-Feb-2019 Applications HEQSF Durban University of Technology 97687 Diploma in Shipping and Logistics NQF Level 06 360 Registered 17-Feb-2019 HEQSF Durban University of Technology 97751 Higher Certificate in Public Administration NQF Level 05 128 Registered 17-Feb-2019 HEQSF Independent Institute of Education 97601 Bachelor of Commerce Honours in Management NQF Level 08 120 Registered 17-Feb-2019 HEQSF Independent Institute of Education 97600 Bachelor of Computer and Information Sciences in Application NQF Level 07 365 Registered 17-Feb-2019 Development HEQSF Milpark Business School 97754 Higher Certificate in Financial Products NQF Level 05 120 Registered 17-Feb-2019 HEQSF Nelson Mandela Metropolitan 97589 Bachelor of Education Honours in Language Education NQF Level 08 120 Registered 17-Feb-2019 University HEQSF Nelson Mandela Metropolitan 97682 Bachelor of Education Honours in Mathematics Education NQF Level 08 120 Registered 17-Feb-2019 University HEQSF Nelson Mandela Metropolitan 97599 Bachelor of Education Honours in Science Education NQF Level 08 120 Registered 17-Feb-2019 University HEQSF Nelson Mandela Metropolitan 97665 Master of Philosophy in Information Technology Governance NQF Level 09 180 Registered