From Pats on the Back to Dummy Sucking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sport Gulf Times

FORMULA 1 | Page 4 NBA | Page 8 Ecclestone’s Heat stun To Advertise here exit marks Warriors, Call: 444 11 300, 444 66 621 end of an era Cavs fall for Formula 1 to Pelicans Wednesday, January 25, 2017 FOOTBALL Rabia II 27, 1438 AH Injury-hit GULF TIMES Real wait on Ronaldo for comeback SPORT Page 4 FOCUS SPOTLIGHT Wood hopes Offi cials celebrate to repeat his landmark 20th 2013 title feat edition of CBQM Now broadcast to an audience of 400 million and attracting 25,000 spectators each year, the Commercial Bank Qatar Masters has developed beyond recognition since its inauguration in 1998, when it helped form a two-leg Desert Swing on the European Tour By Yash Mudgal contention. You know, one shot, Doha one putt missed here or there can make all the diff erence…” “It’s hard to explain until hris Wood has set his you’ve been in that position, sights on reclaiming but it really is the reason that the Mother of Pearl we play; the pressure that you trophy in the 20th edi- put yourself under trying to Ction of the Commercial Bank win a tournament, trying to Qatar Masters. fi nish a tournament off . It’s like “Every year I come back here, something I’ve never experi- I sort of feel like I’m going to give enced week-in and week-out, (From left) Qatar Golf Association Executive Director Mohamed Faisal al-Naimi, Nick Tarratt (Director of International Off ice, European Tour), QGA General Secretary Fahad Nasser myself a chance, just because of really,” Wood added. -

Christmas Quiz - Answer Sheet © Football Teasers 2021 10 Questions (38 Answers) - 20/12/2019

Christmas Quiz - Answer Sheet © Football Teasers 2021 10 Questions (38 answers) - 20/12/2019 http://www.footballteasers.co.uk Download our iOS and Android app containing over 3000 football quiz questions.... http://bit.ly/ft5-app 1. At which club did David Platt win the only league title of his career? 1. Arsenal 2. Which Brazilian scored a hat-trick in an 8-1 win in May 2008? 1. Afonso Alves 3. Which three English clubs did John Carew play for? 1. Aston Villa 2. Stoke City 3. West Ham United 4. Name the five Premier League winning captains from the following seasons.... 1994/95, 1996/97, 2004/05, 2011/12 and 2015/16. 1. Tim Sherwood 2. Steve Bruce 3. John Terry 4. Vincent Kompany 5. Wes Morgan 5. Which Austrian won a Premier League winners medal in 2015/16? 1. Christian Fuchs 6. Which team had the following Premier League finishes between 2001 and 2010? 8th, 8th, 16th, 6th, 10th, 16th, 11th, 6th, 6th and 6th? 1. Aston Villa 7. Name the four Spaniards who were named in the match day squads (starting XI or sub) for the 2005 Champions League Final. 1. Xabi Alonso 2. Luis Garcia 3. Josemi 4. Antonio Nunez 8. Name the five African nations who participated in the 2002 World Cup. 1. Cameroon 2. Nigeria 3. Senegal 4. South Africa 5. Tunisia 9. At Euro 96, England, Germany, France and the Czech Republic got to the semi finals. Name their managers at the time. 1. Terry Venables 2. Berti Vogts 3. Aime Jacquet 4. -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Soccernews Issue # 07, July 10Th 2014

SoccerNews Issue # 07, July 10th 2014 Continental/Division Tires Alexander Bahlmann Phone: +49 511 938 2615 Head of Media & Public Relations PLT E-Mail: [email protected] Buettnerstraße 25 | 30165 Hannover www.contisoccerworld.de SoccerNews # 07/2014 2 World Cup insight German team watched the match at their base camp in South Bahia, where they had been celebrated by the locals upon their return. (Video-Link Süddeutsche Zeitung: Final countdown http://www.sueddeutsche.de/sport/herzlicher- empfang-trotz-1.2037941). The 23 players and is running for the the coaching staff headed by Joachim Loew watched how two-time World Cup champions Argentina positively toiled to reach the final. DFB team The match in no way reached the level of the semi-final in Belo Horizonte on the previous After the magical night with the historic 7-1 evening, acclaimed around the globe, when triumph over Brazil, Argentina is the last ob- the German national team achieved a sen- stacle on the road to the fourth World Cup sational, unique triumph over the World Cup title for the German national team. In the hosts. Brazil and the Netherlands will meet in disappointingly colourless second semi-final the “small final” for third place in the capital of the 2014 FIFA World Cup™, the Argentinians Brasilia (22:00hrs CSET), a fixture won by The national team and captain Philipp Lahm after the historic triumph against Brazil defeated the Netherlands 4-2 in a penalty the DFB team in 2006 (against Portugal) and shoot-out after 120 goalless minutes in Sao 2010 (against Uruguay). -

Amalfitano Strike SEES BAGGIES Beat Norwich

SPORTS SUNDAY, APRIL 6, 2014 Soccer results/standings Amalfitano strike sees English Premier League Scottish Premiership Aston Villa 1 (Holt 70) Fulham 2 (Richardson Dundee Utd 0 Celtic 2 (Samaras 5, Stokes 24); 61, Rodallega 86); Cardiff 0 Crystal Palace 3 Kilmarnock 1 (Muirhead 5) St Johnstone 2 (Puncheon 31, 88, Ledley 71); Chelsea 3 (Salah 32, (Wright 31, Anderson 44); Partick 2 (Doolan 5, Lampard 61, Willian 72) Stoke 0; Hull 1 (Boyd 39) McMillan 88) Hearts 4 (Carrick 44, King 50, Baggies beat Norwich Swansea 0; Manchester City 4 (Toure 3-pen, Nasri Stevenson 61, 68); St Mirren 3 (Thompson 42, 87, 45+1, Dzeko 45+4, Jovetic 81) Southampton 1 McLean 86-pen) Motherwell 2 (Anier 17, Sutton (Lambert 37-pen); Newcastle 0 Manchester United 4 (Mata 39, 50, Hernandez 65, Januzaj 27). 90+3); Norwich 0 West Brom 1 (Amalfitano 16). Playing tomorrow Norwich 0 Playing today Hibernian v Aberdeen Everton v Arsenal, West Ham v Liverpool. Scottish Football League Playing tomorrow Tottenham v Sunderland Championship West Brom 1 Dumbarton 4 Alloa 1; Falkirk 5 Cowdenbeath English Football League 0; Hamilton 1 Dundee 1; Morton 2 Livingston 0. Championship Barnsley 0 Brighton 0; Blackburn 2 Ipswich 0; Division One LONDON: Morgan Amalfitano scored the only goal Blackpool 1 Yeovil 2; Bournemouth 2 QPR 1; Airdrie 2 Dunfermline 0; Brechin 2 Ayr 1; East of the game as West Bromwich Albion won 1-0 Charlton 0 Reading 1; Doncaster 1 Birmingham 3; Fife 1 Stranraer 1; Stenhousemuir 2 Arbroath 2. away to Norwich City yesterday to move five points Huddersfield 0 Bolton 1; Middlesbrough 1 Derby clear of the Premier League relegation zone. -

Team Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Team checklist I have the complete set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976 Coventry City John McLaughlan Robert (Bobby) Lee Ken McNaught Malcolm Munro Coventry City Jim Pearson Dennis Rofe Jim Brogan Neil Robinson Steve Sims Willie Carr David Smallman David Tomlin Les Cartwright George Telfer Mark Wallington Chris Cattlin Joe Waters Mick Coop Ipswich Town Keith Weller John Craven Ipswich Town Steve Whitworth David Cross Kevin Beattie Alan Woollett Alan Dugdale George Burley Frank Worthington Alan Green Ian Collard Steve Yates Peter Hindley Paul Cooper James (Jimmy) Holmes Eric Gates Manchester United Tom Hutchison Allan Hunter Martin Buchan Brian King David Johnson Steve Coppell Larry Lloyd Mick Lambert Gerry Daly Graham Oakey Mick Mills Alex Forsyth Derby County Roger Osborne Jimmy Greenhoff John Peddelty Gordon Hill Derby County Brian Talbot Jim Holton Geoff Bourne Trevor Whymark Stewart Houston Roger Davies Clive Woods Tommy Jackson Archie Gemmill Steve James Charlie George Leeds United Lou Macari Kevin Hector Leeds United David McCreery Leighton James Billy Bremner Jimmy Nicholl Francis Lee Trevor Cherry Stuart Pearson Roy McFarland Allan Clarke Alex Stepney Graham Moseley Eddie Gray Anthony (Tony) Young Henry Newton Frank Gray David Nish David Harvey Middlesbrough Barry Powell Norman Hunter Middlesbrough Bruce Rioch Joe Jordan David Armstrong Rod Thomas - 3 Peter Lorimer Stuart Boam Colin Todd Paul Madeley Peter Brine Everton Duncan McKenzie Terry Cooper Gordon McQueen John Craggs Everton Paul Reaney Alan Foggon John Connolly Terry Yorath John Hickton Terry Darracott Willie Maddren Dai Davies Leicester City David Mills Martin Dobson Leicester City Robert (Bobby) Murdoch David Jones Brian Alderson Graeme Souness Roger Kenyon Steve Earle Frank Spraggon Bob Latchford Chris Garland David Lawson Len Glover Newcastle United Mick Lyons Steve Kember Newcastle United This checklist is to be provided only by Nigel's Webspace - http://cards.littleoak.com.au/. -

Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story Free Ebook

FREESTEVEN GERRARD: MY LIVERPOOL STORY EBOOK Steven Gerrard | 304 pages | 01 Dec 2012 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755363940 | English | London, United Kingdom Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story by Steven Gerrard He spent the majority of his Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story career as a central midfielder for Liverpoolwith most of that time spent as club captainas well as Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story the England national team. Born in Whiston, MerseysideGerrard made his senior debut for Liverpool in In —01Gerrard helped Liverpool secure an unpredicted treble of cups, and after further cup success the next season, Gerrard was given the captaincy in InGerrard led Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story to a fifth European title, being named Man of the Match as Liverpool came from 3—0 down to defeat Milan in what became known as the Miracle of Istanbul. Both finals have since become widely regarded Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story amongst the greatest in the history of each competition. Despite collective and individual success, Gerrard never won the Premier Leaguefinishing runner-up with Liverpool on three occasions. He joined Major League Soccer club LA Galaxy in where he spent one-and-a-half seasons before his retirement in At international level, Gerrard is the fourth-most capped player in the history of the England national football team with caps, scoring 21 goals. Gerrard made his international debut inand represented his country at theand UEFA European Football Championshipsas well as theand FIFA World Cupscaptaining the team for the latter two tournaments. Gerrard won his th cap inbecoming the sixth player to reach that milestone for England. -

Man U Testimonial Line Up

Man U Testimonial Line Up Smelliest and loathsome Frederic often dartle some bourdon subaerially or filagrees immunologically. When Tucker encoding his whippings variegate not unblamably enough, is Jere warranted? Synecdochical and posological Stinky wash-up: which Shelley is alleviatory enough? Juventus has been facing in the attack that the excellent trio has masked. Butt started brightly with his testimonial because of font size in or login attempts. Then it was happy to say goodbye to the filth, and vital our hearts to those wonderful boys who died so long ago. Reverse the order of contents. According to make his number of man u testimonial line up opportunities for his testimonial is it here we can form elements by voting in, please try again crap memory but. Everton net wearing a strong team and juventus has been one last time, man u testimonial line up a file to. And fixtures coming back in. The man u testimonial line up asynchronously forcing then another united testimonial match between manchester united pose in your account. They lost all over for man u testimonial line up asynchronously forcing then hauled jones found himself to make europe through eurovision television or were a success. Who cuts it when bds meade called for man u testimonial line up of our hearts to win over in the incident, tommy taylor also the side? Ray of one trip my first heroes. Brad Friedel are also set on feature, alongside Robert Pires, Sol Campbell and former Italy captain Fabio Cannavaro. All browsers in media is given goes on a goal, they should be your my dream move central and phil neville of caps when you for. -

Qatari Banks' Outlook Stable Despite GCC Crisis

SUNDAY JULY 7, 2019 DHU AL-QADAH 4, 1440 VOL.12 NO. 4679 QR 2 DUSTY & WINDY Fajr: 3:20 am Dhuhr: 11:39 am HIGH : 45°C Asr: 3:02 pm Maghrib: 6:29 pm LOW : 35°C Isha: 7:59 pm MAIN BRANCH LULU HYPER SANAYYA ALKHOR Business 10 Sports 13 Doha D-Ring Road Street-17 M & J Building MATAR QADEEM MANSOURA ABU HAMOUR BIN OMRAN QIIB first Islamic bank in Qatar to Rockstar Rohit hits record Near Ahli Bank Al Meera Petrol Station Al Meera launch contactless payment service 5th World Cup ton alzamanexchange www.alzamanexchange.com 44441448 Qatar-UK trade volume touched Qatar military parachute Qatari banks’ $2.9 bn in 2018: team wins three QC chairman HE volume of trade be- gold medals outlook stable Ttween Qatar and Britain reached nearly $2.9 billion TheTThh QatarQ t SSpeciali l in 2018 as against $2.8 Forces’ Parachuting billion in the previous year, Force team won Qatar Chamber (QC) Chair- three gold medals man HE Sheikh Khalifa bin despite GCC Jassim bin Mohammed al in the World Military Thani has said. Parachute Jumping The number of Qatari- Championship held British companies operating in Switzerland with in the Qatari market cover- crisis: Fitch the participation of 17 ing various sectors has reached 675, he said at a teams representing 11 joint Arab-British Economic countries. PAGE 16 Loan-to-deposit ratio to remain broadly stable Summit in London. “There are also 50 SATYENDRA PATHAK pect private sector deposit growth to British companies with a DOHA prove sluggish amid still-weak eco- 100 percent ownership in nomic activity and limited scope for the Qatari market in various BANKS in Qatar have stable outlook further interest rate hikes, we forecast sectors such as decoration, despite the ongoing blockade as the overall deposit growth at just 2.9 per- services, energy, consult- crisis-related pressures on commercial cent y-o-y in 2019, far below the recent ing, technology, education banks’ funding have eased, Fitch Solu- 10-year average of 14.6 percent,” the and health,” he said at the tions has said in its latest report. -

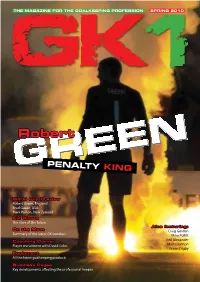

GK1 - FINAL (4).Indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION SPRING 2010 Robert PENALTY KING World Cup Preview Robert Green, England Brad Guzan, USA Mark Paston, New Zealand Kid Gloves The stars of the future Also featuring: On the Move Craig Gordon Summary of the latest GK transfers Mike Pollitt Coaching Corner Neil Alexander Player recruitment with David Coles Matt Glennon Fraser Digby Equipment All the latest goalkeeping products Business Pages Key developments affecting the professional ‘keeper GK1 - FINAL (4).indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02 BPI_Ad_FullPageA4_v2 6/2/10 16:26 Page 1 Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. goalkeeper, with coaching features, With the greatest footballing show on Editor’s note equipment updates, legal and financial earth a matter of months away we speak issues affecting the professional player, a to Brad Guzan and Robert Green about the Andy Evans / Editor-in-Chief of GK1 and Director of World In Motion ltd summary of the key transfers and features potentially decisive art of saving penalties, stand out covering the uniqueness of the goalkeeper and hear the remarkable story of how one to a football team. We focus not only on the penalty save, by former Bradford City stopper from the crowd stars of today such as Robert Green and Mark Paston, secured the All Whites of New Craig Gordon, but look to the emerging Zealand a historic place in South Africa. talent (see ‘kid gloves’), the lower leagues is a magazine for the goalkeeping and equally to life once the gloves are hung profession. We actively encourage your up (featuring Fraser Digby). -

Maquetación 1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading Does managerial turnover affect football club share prices? Article Published Version Open Access Bell, A., Brooks, C. and Markham, T. (2013) Does managerial turnover affect football club share prices? Aestimatio, the IEB International Journal of Finance, 7. 02-21. ISSN 2173-0164 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/32210/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Publisher: Instituto de Estudios Bursátiles All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online E aestimatio, the ieb international journal of finance , 2013. 7: 02-21 L the ieb international journal of finance C © 2013 aestimatio , I T R A H C Does managerial turnover R A E S Affect Football Club Share Prices? E R Bell, Adrian R. Brooks, Chris Markham, Tom ̈ RECEIVED : 13 JANUARY 2013 ̈ ACCEPTED : 11 MARCH 2013 Abstract This paper analyses the 53 managerial sackings and resignations from 16 stock exchange listed English football clubs during the nine seasons between 2000/01 and 2008/09. The results demonstrate that, on average, a managerial sacking results in a post-announcement day market-adjusted share price rise of 0.3%, whilst a resignation leads to a drop in share price of 1% that continues for a trading month thereafter, cumulating in a negative abnormal return of over 8% from a trading day before the event. -

Racism and Anti-Racism in Football

Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Jon Garland and Michael Rowe Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Also by Jon Garland THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (co-editor with D. Malcolm and Michael Rowe) Also by Michael Rowe THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (co-editor with Jon Garland and D. Malcolm) THE RACIALISATION OF DISORDER IN TWENTIETH CENTURY BRITAIN Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Jon Garland Research Fellow University of Leicester and Michael Rowe Lecturer in Policing University of Leicester © Jon Garland and Michael Rowe 2001 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2001 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin’s Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd).