Addressing the Needs of the Homeless: a San José Library Partnership Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Jose Public Library California Room Silicon Valley History Online Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7k4023tp Online items available Guide to the San Jose Public Library California Room Silicon Valley History Online Collection San Jose Public Library California Room staff San Jose Public Library California Room Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library University of California 150 E. San Fernando St. San Jose, California 95112 Phone: (408) 808-2167 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.sjlibrary.org/research/special/ca/ © 2005 San Jose Public Library Guide to the San Jose Public Consult repository 1 Library California Room Silicon Valley History Online Collection Descriptive Summary Title: San Jose Public Library California Room Silicon Valley History Online collection Dates: 1859-1991 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1890-1940) Collection number: Consult repository Collector: San Jose Public Library California Room Collection Size: 119 items119 online items Repository: San Jose Public Library California Room. San Jose, California 95112 Abstract: The San Jose Public Library California Room collection includes books, photographs, maps, periodicals, clippings and ephemera. The collection covers all of California with special emphasis on San Jose and Santa Clara County. The majority of images chosen for this project were photographs selected from the California Room Photograph collection and the Arbuckle Photograph collection. Also included are ephemera and postcards. The images document businesses, street scenes, agriculture, government, transportation, buildings and special events located in San Jose and Santa Clara County. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt7k4023tp Access Collection open for research. Publication Rights The San Jose Public Library California Room can only claim physical ownership of the collection. -

HONORABLE MAYOR FROM: Jill Bourne and CITY COUNCIL

TO: HONORABLE MAYOR FROM: Jill Bourne AND CITY COUNCIL SUBJECT: SJ ACCESS – STUDENT HOTSPOT DATE: April 29, 2021 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Approved Date 4/29/2021 INFORMATION This memorandum provides a detailed overview of the SJ Access – Student Hotspot program, which has provided 12,800 student households with a hotspot and a high-speed unlimited data plan for the main purpose of connecting to distance learning. As noted in the Rules and Open Government Committee Meeting on April 7, 2021, an Informational Memorandum was requested to provide an overview of the Student Hotspot program, in lieu of the deferred Annual Report of the Education and Digital Literacy Strategy, to be heard by the Neighborhood Services and Education Committee in Fall 2021. A single page overview of the program is provided as Attachment A. School Closures On March 13, 2020, the Santa Clara County Office of Education (SCCOE) announced that beginning on Monday, March 16, 2020, schools in Santa Clara County would shift to distance learning in response to growing cases of COVID-19 in the community. This closure was originally announced for a three-week duration and preceded the March 16 announcement of a regional Shelter-in-Place order. With few exceptions, schools remained closed and relied on distance learning programs through June 2020, and remained closed for the majority of the 2020- 2021 school year until April 2021, when Local Education Agencies (LEAs) began large-scale reopening plans, many of which include a hybrid learning approach (leveraging both distance and in-person learning). Addressing Insufficient Connectivity On April 21, 2020, staff provided the City Council with an update on digital access and inclusion efforts, specifically related to the need to assist schools and students during the COVID-19 pandemic. -

![National Register of Historic Places I ] §Gp Registration Form I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1130/national-register-of-historic-places-i-%C2%A7gp-registration-form-i-881130.webp)

National Register of Historic Places I ] §Gp Registration Form I

(Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places I ] §gp Registration Form i • _ _„_....—•- This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. ?See instructions in Hovy to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete eaihJtem by marking"x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicaole." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________RELt^Fn/r''!^ historic name Alviso, Jose Maria, Adob°—————————————— other names/site number CA-SC1 -15? ___________________ 2. Location street & number Q? P-jprfmnnt- Pnari ___________________________ G not for publication city or town Mi Ip-it-ac;_____________________________________ D vicinity state ______rj=n -ifn-rnia code CA county fianivi ria-ra_____ code ngc; zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, 1 hereby certify that this^Q nomination Q request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S3 meetdlO does not meet the National Register criteria 1 recommend that this property be considered significant d nationally £H stat§wid^ Q/tocally. -

SJSU Top Employers and Industries 2017 - 2018 Graduates

SJSU Top Employers and Industries 2017 - 2018 Graduates SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY EMPLOYERS (6 or more hires) INDUSTRIES (21 or more hires) Adobe Systems P,E Accounting Amazon P,E Automotive Apple P,E Biotech & Life Sciences Cisco P,E Civil Engineering City of San José P,E Commercial Banking & Credit County of Santa Clara P,E Computer Networking EY P Construction Facebook P Electronic & Computer Hardware Google, Inc. P,E Food & Beverage Grant Thornton P,E Government - Local, State & Federal Intel Corporation P,E Healthcare Kaiser Permanente P,E Higher Education KPMG LLP P Internet & Software Lockheed Martin P,E K-12 Education Oracle P,E Legal & Law Enforcement San José State University P,E Manufacturing - Other San José Unified School District Management Consulting SAP Center P Non-Profit - Other Self-Employed Research Stanford University P,E Restaurants & Food Service Starbucks Coffee Company P Retail Stores Target Corporation P,E Social Assistance Tesla P,E Sports & Leisure Uplift Family Services P,E Transportation & Logistics Valley Medical Center Foundation P Western Digital P,E P = Employer posts opportunities in SJSU Handshake, the campus' digital career resources platform E = Employer participates in on-campus recruiting activities offered by the SJSU Career Center 1 SJSU Top Employers and Industries 2017 - 2018 Graduates CHARLES W.DAVIDSON COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING EMPLOYERS (2 or more hires) INDUSTRIES (5 or more hires) Amazon P,E Aerospace Apple P,E Automotive Cisco P,E Civil Engineering eBay P Commercial Banking & Credit Facebook P Computer Networking Google, Inc. P,E Construction Granite River Labs P Defense IBM P,E Electronic & Computer Hardware Integrated Device Technology P Government - Local, State & Federal Intel Corporation P,E Healthcare Intuit, Inc. -

Education and Digital Literacy Annual Report Page 2

TO: LIBRARY AND EDUCATION FROM: Jill Bourne COMMISSION SUBJECT: Education and Digital Literacy DATE: March 10, 2021 Annual Report Approved Date RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Library and Education Commission take the following actions related to the Education and Digital Literacy Strategy Update: • Review the annual report on the implementation of the Education and Digital Literacy Strategy including the implementation of the Quality Standards, relationships with schools and school districts, and the evolution of City programs; • Review and provide feedback regarding program plans for Fiscal Year 2020-21; • Direct staff to return to the Library and Education Commission annually to report on progress implementing the Education and Digital Literacy Strategy. OUTCOME The Library and Education Commission (LEC) will be informed and provide feedback to staff on the annual report of the implementation of the Education and Digital Literacy Strategy, including implementation of program Quality Standards, relationships with schools and school districts, and the evolution of City programs. BACKGROUND On May 7, 2018, City Council unanimously approved the Education & Digital Literacy (EDL) Strategy1, and designated San José Public Library (“SJPL”, “Library”) as lead department, with direction to devise and implement a comprehensive educational policy and workplan for the following educational development areas: • Early Education - Entering School Ready to Learn and Succeed; 1 Education and Digital Literacy Strategy.pdf Library and Education -

Annual Report

Metropolitan Education District ANNU A L REPO R T 2009-2010 May 2010 CCOC Awards Night Career Fashion June 2010 MAEP Graduates Show - Electrical Maintenance Students We are ALL about student success! MetroED is fully accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC). Welcome to MetroED! SUPERINTENDENt’S MESSAGE BOARD PRESIDENt’S MESSAGE 2009-10 was the first year that MetroED felt As President of the MetroED Board it is my the full impact of 20% state cuts to ROC/P and pleasure to present the 2009-10 annual Adult Education funding. Steps taken during report. MetroED serves the community with 2008-09 and 2009-10 to reduce our costs were schools in Campbell Union High School effective in bringing our on-going expenses in District, East Side Union High School District, line with reduced funding. Los Gatos-Saratoga Joint Union High School District, Milpitas Unified School District, San I would like to acknowledge and thank the San Jose Unified School District and Santa Clara Jose Job Corps for helping MetroED balance its Unified School District. budget during this funding crisis. Job Corps has long been a partner with MetroED, sending students to CCOC On behalf of the MetroED Governing Board, we want to thank and MAEP, running ROP classes on their San Jose campus and the students, staff and community for a great year. The six sending students to the MAEP GED Testing Center. Job Corps, participating school district representatives to the Governing which is federally funded, has stepped up to help MetroED during Board of MetroED provide a diversity of knowledge and these difficult budget times by directly hiring the ROP teachers on experience to provide an exceptional learning environment their San Jose Campus, paying class fees for their students and for the juniors and seniors from our high schools at CCOC. -

SVR 2013 Calendar of Events

Silicon Valley Reads 2013 “Invisible Wounds of War” Calendar of 100+ Events January-April, 2013 Authors • Panels • Films • Art Exhibit • Discussions Free events for all ages throughout Santa Clara County PRESENTED BY: SiliconValleyReads.org Welcome to Silicon Valley Reads 2013 After the Civil War, men returning from combat in Santa Clara County to read and think about 2013 Companion Books suffered from “soldier’s heart.” In World War I, this important topic. Through our selected for Children & Teens some experienced “Shell Shock” and in World books and more than 100 free public events for War II it was labeled “Battle Fatigue.” Since all ages, Silicon Valley Reads hopes to engage Night Catch [PreK-Gr 2] by Brenda Ehrmantraut Vietnam, veterans have been diagnosed the community in apolitical discussions about Nubs: The True Story of a Mutt, a Marine and a with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) the after effects of war on soldiers and their Miracle [Gr 2-5] by Brian Dennis, Kirby Larson or Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Every war is families. and Mary Nethery different, but all leave indelible psychological, Back Home [Gr 5-8] by Julia Keller emotional and spiritual scars on those who 2013 Featured Books serve and those who wait at home. The Long Walk: A Story of War and the Life That Purple Heart [Teens] by Patricia McCormick Follows by Brian Castner In 2013, Silicon Valley Reads explores the theme of “Invisible Wounds of War” and asks everyone Minefields of the Heart: A Mother’s Stories of a Son at War by Sue Diaz Kick Off of Silicon Valley Reads 2013 Wednesday, Jan. -

End Local Hunger Welcome

CELEBRATING YOUR COMMITMENT TO END LOCAL HUNGER WELCOME Welcome to Second Harvest Food Bank’s Make Hunger History Awards! In Silicon Valley, we’re incredibly fortunate to live Working adults can keep a roof over their heads and in a land of opportunity and innovation. But when we food in their refrigerators. look past the start-ups and self-driving cars, we see Because of your continued support, we can make the faces of people in need who struggle everyday. a tangible difference for our neighbors in need. Your Those faces might surprise you. They are employed, commitment and passion for this work enabled us educated, and hard working. The face of hunger is a to provide more than 56 million meals to hungry mother with two jobs who has to sell her television families last year, and distribute more fresh produce to put food on the table, or a sixth grader eating than any food bank in the country. With your help expired food. we launched an innovative client managed pantry at Sacred Heart Nativity School in San Jose, and Hunger is all consuming. Our clients are forced to added quality protein and dairy items to improve make intense choices about their basic needs each the nutritious ‘mix’ of foods we distribute. day. In fact, we know that 35% of our clients water down their food and drinks to stretch meals, and Thank you for serving as ambassadors, leaders, 23% sell or pawn their personal property so that and champions in the community that we treasure they can eat. -

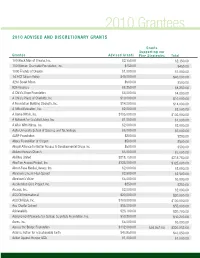

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

GOSBGF SPPE Application Appendices

DOCKETED Docket Number: 20-SPPE-01 Great Oaks South Backup Generating Facility Small Power Project Title: Plant Exemption TN #: 232467-3 Document Title: GOSBGF SPPE Application Appendices H-K Description: N/A Filer: Scott Galati Organization: DayZenLLC Submitter Role: Applicant Representative Submission Date: 3/19/2020 2:29:29 PM Docketed Date: 3/19/2020 Appendix H Noise Report EQUINIX SV12, SV18, AND SV19 PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL NOISE AND VIBRATION ASSESSMENT San José, California December 23, 2019 Prepared for: Julie Wright David J. Powers & Associates, Inc. 1871 The Alameda, Suite 200 San José, CA 95126 Prepared by: Steve J. Deines Dana M. Lodico, PE, INCE Bd. Cert. 429 E. Cotati Avenue Cotati, CA 94931 (707) 794-0400 Project: 19-176 INTRODUCTION This report assesses the noise and vibration impacts resulting from the construction and operation of the Equinix SV12, SV18, and SV19 Data Centers project proposed to the north of Santa Teresa Boulevard, between San Ignacio Avenue and Great Oaks Boulevard in San José, California. The project would develop the northeastern 18-acres of the 34-acre site with three (3) three-to-four- story data center buildings totaling approximately 564,000 square feet (sf). A total of 36 3.25-MW diesel-fueled generators would be located within generator yards located adjacent to the north and south sides of each building. The 36 generators would provide 117 MW of backup power generation capacity. The report is divided into three sections: 1) the Setting Section provides a brief description of the fundamentals of -

Research Files

McKay Research Files - Folder Listing: Agnews Airport & Jim Nissen Airport Airport noise & airport expansion San Jose airport: talk at Rotary The Alameda and Hester Park The Alameda: Living History Day, 1998-10-04 Alexian brothers: hospital rename Alma Alum Rock carousel Alum Rock mineral springs Alum Rock park & railroad Adkins, Walt: Chief of Police Alviso's: Vahl, Amelia American Revolution - men of/disasters Antique printing equipment: Lindner Press Architects - San Jose & Santa Clara County Kort Arada family/ Haenlen Orange Mill Clyde Arbuckle memorial - 2000-01-10 Clyde Arbuckle commemoration - grant form Clyde and Helen Arbuckle Clyde Arbuckle's History of San Jose Jim Arbuckle (Redding) San Jose sewage disposal plant - Alviso San Joseans - Joseph Aram 1906 aerial photo of San Jose - by George Lawrence Notes on Pioneer talk - San Jose artists - 1998-07-03 Bossack - art restorer, Capitola Argonauts - Donner Trail Audio/video TV tapes - Local history Austin Corners - Los Gatos, Saratoga Rd. Award nominations Backesto Park People of San Jose - John Ball Richard Barrett Bancroft Library, Berkeley - Peralta and early Pueblo Bascom Monument - Oak Hill - dedicated 2000-09-09 - donations, etc. Grandma Bascom's Story, 1887 - interview in Overland Monthly, 1887 Grandma Bascom - script Battle of Santa Clara - speech to campers - 1978-10-14 Jack Bean book - sticker info Bear Flag Republic Bees, Honey - introduced to California - Clyde Arbuckle story Begonias - Antonelli Brothers Bellarmine - history, 1922-1934 Benech (?) - El Pirul migrant -

Memorandum CAPITAL of SILICON VALLEY

CED COMMITTEE: 1/27/20 ITEM: D (2) CITY OF SAN JOSE Memorandum CAPITAL OF SILICON VALLEY TO: HONORABLE MAYOR FROM: Chris Burton AND CITY COUNCIL SUBJECT: BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT DATE: January 13, 2020 AND SMALL BUSINESS UPDATE Approved ^ ■ /( RECOMMENDATION Accept staffs report on services provided by the City and its partners to support the startup, growth, and retention of businesses in San Jose. BACKGROUND Businesses play a key role in ensuring the fiscal, social, and cultural health of nearly all cities. Whether large or small, businesses may provide jobs, generate tax revenue and contribute to a sense of place for a community. In San Jose, a business ecosystem of roughly 53,000 establishments employs approximately 438,000 people. Businesses are expected to contribute $258 million to the City just in sales tax alone for FY2019-20, which is equivalent to nearly 20 percent of the City’s general fund. Less quantifiable benefits include the activation of neighborhood business corridors, wealth creation within disadvantaged communities, and the pride that comes with hosting a strong commercial enterprise or unique company. San Jose’s unemployment rate in November of 2019 was just 2.4 percent, which is among the lowest rates in at least 10 years in San Jose. That equates to about 13,500 unemployed people who are actively looking for work. Five years ago, there were 30,400 unemployed people in San Jose looking for work, an unemployment rate of 5.8 percent. San Jose’s largest industries are, in order, manufacturing; government; professional, scientific and technical services (PSTS); health care; and retail trade.