Why Expert Testimony on the Reliability of Eyewitness Testimony Is Unwarranted in Alabama State Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Circuit Court of Walker County, Alabama

ELECTRONICALLY FILED 10/30/2009 6:18 PM CV-2007-000400.00 CIRCUIT COURT OF WALKER COUNTY, ALABAMA SUSAN ODOM, CLERK IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF WALKER COUNTY, ALABAMA CHARLES BAKER, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. CV-07-400 ) WALKER COUNTY BINGO, et al., ) ORAL ARGUMENT SET: ) November 2, 2009 – 2:00 p.m. Defendants. ) ) DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL COME NOW Agape Ministries, Building Fund of Nauvoo; Capers Chapel CME Church; Carbon Hill High School; Church Upon the Rocks; Cordova Fire Department; Court of Calanthe; Curry High Athletics; Curry High School; Farmstead Athletic Association; Granny’s Closet; Ladies Auxiliary of Nauvoo; Minnie’s Helping Hands; Mt. Carmel Cemetery Organization, Inc.; Mr. Zion ME Church; Mr. Park @ Yerkwood, AL; Nauvoo Beautification Committee; Nauvoo Park & Recreation; Old Country Thrift Store; Parrish High School; Sipsey Church of God Ladies Auxiliary; Sipsey Community Center; Sipsey Fire Department; Sipsey Food Bank; Sipsey Recreation Center; Sipsey School; Sipsey Volunteer Fire & Rescue Department; St. Cecilia’s Church Youth Group; The Portal Student Center; TS Boyd School; Walker County Cruisers; Walker County Honor Guard, Inc.; Walker County Women’s Bowling Association; Wrights Chapel AME Church; Yerkwood Youth Club, Inc.; House of Prayer; Farmstead Toybowl Cheerleaders; Lupton Little League; Walker Independent Theater; Mathis Creek Cemetery; Barney Volunteer Fire Department; Pineywoods Fire Department; Files Cemetery; Farmstead Athletic Association; Manchester Community Center; -

Compelling and Staying Arbitration in Alabama

Resource ID: w-010-6758 Compelling and Staying Arbitration in Alabama MICHAEL P. TAUNTON AND GREGORY CARL COOK, BALCH & BINGHAM, LLP, WITH PRACTICAL LAW ARBITRATION Search the Resource ID numbers in blue on Westlaw for more. A Practice Note explaining how to request DETERMINE THE APPLICABLE LAW judicial assistance in Alabama state court to When evaluating a request for judicial assistance in arbitration proceedings, the court must determine whether the arbitration compel or stay arbitration. This Note describes agreement is enforceable under the FAA or Alabama state law. what issues counsel must consider before The FAA seeking judicial assistance and explains the An arbitration agreement falls under the FAA if the agreement: steps counsel must take to obtain a court order Is in writing. compelling or staying arbitration in Alabama. Relates to: za commercial transaction; or za maritime matter. SCOPE OF THIS NOTE States the parties’ agreement to arbitrate a dispute. (9 U.S.C. § 2.) When a party commences a lawsuit in defiance of an arbitration agreement, the opposing party may need to seek a court order to The FAA applies to all arbitrations arising from maritime transactions stay the litigation and compel arbitration. Likewise, when a party or to any other contract involving “commerce,” a term the courts starts an arbitration proceeding in the absence of an arbitration define broadly. However, even if the arbitration agreements agreement, the opposing party may need to seek a court order falls under the FAA, parties may contemplate enforcement of staying the arbitration. This Note describes the key issues counsel their arbitration agreement under state law (see Hall St. -

Between Fraud Heaven and Tort Hell: the Business, Politics, and Law of Lawsuits

Between Fraud Heaven and Tort Hell: The Business, Politics, and Law of Lawsuits by Anna Johns Hrom Department of History Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Supervisor ___________________________ Sarah Jane Deutsch ___________________________ Philip J. Stern ___________________________ Melissa B. Jacoby ___________________________ Benjamin Waterhouse Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Between Fraud Heaven and Tort Hell: The Business, Politics, and Law of Lawsuits By Anna Johns Hrom Department of History Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Supervisor ___________________________ Sarah Jane Deutsch ___________________________ Philip J. Stern ___________________________ Melissa B. Jacoby ___________________________ Benjamin Waterhouse An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Anna Johns Hrom 2018 Abstract In the 1970s, consumer advocates worried that Alabama’s weak regulatory structure around consumer fraud made it a kind of “con man’s heaven.” But by the 1990s, the battle cry of regulatory reformers had reversed, as businesspeople mourned the state’s decline into “tort hell.” Debates -

Supreme Court of Alabama

REL: 05/08/2015 Notice: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the advance sheets of Southern Reporter. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Alabama Appellate Courts, 300 Dexter Avenue, Montgomery, Alabama 36104-3741 ((334) 229-0649), of any typographical or other errors, in order that corrections may be made before the opinion is printed in Southern Reporter. SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA OCTOBER TERM, 2014-2015 _________________________ 1120666 _________________________ Kevin Geeslin v. On-Line Information Services, Inc., and Chief Justice Roy S. Moore Appeal from Montgomery Circuit Court (CV-12-901574) MURDOCK, Justice. Kevin Geeslin filed this action challenging a "convenience fee" and "token fee" charged in connection with his on-line electronic filing of a civil action –- fees 1120666 assessed in addition to the statutorily defined filing fee that were mandated by a September 6, 2012, administrative order issued by then Chief Justice Charles Malone. That order purported to make mandatory the on-line, or electronic, filing of all documents filed in civil actions in Alabama circuit courts and district courts by parties represented by an attorney. Alabama's on-line document-filing system, known as "AlaFile," requires credit-card payment of filing fees and charges users a "convenience fee" in addition to the filing fees. Geeslin filed this putative class action in the Montgomery Circuit Court, naming as defendants Chief Justice Malone in his official capacity1 and On-Line Information Services, Inc. ("On-Line"), the company that manages and maintains the electronic-filing system for the Alabama Administrative Office of Courts ("AOC"). -

May 1994/ 129 in BRIEF Theafl'yer Alabama

One malpractice insurer is dedicated to continually serving only Alabama Attorneys and remaining in the Alabama marketplace! AIM: For the Diff ere nee! Attorn eys In sur ance Mutu al of Alabama. Inc ."' 22 ln11ornoss Contor Parkway Te lephone (205) 980-0009 Sul1o 525 Toll Free (800) 526·12 4 6 ClBirmingham, A labama 35242 -4 889 FAX(205)980 - 9009 ·CHA RTER MEMBE R: NATION AL ASSOC IATION OF BAR-RELATED INSURANCE COMPAN IES. Two Special Offers From When it comes to bar association member Th e Employee-Own ers of Avis benefits, Avis always rules in yo ur favor. ·we try Exclusive ly For Members or harder" by o fferin g you low. co mpetitive daily Alabam a State Bar business rates along wi th special d.iscounts for both business and leisure rentals. And just for the record, now you can enjoy valuable offers like a fr ee upgrade and $10 off a CaseClosed! weekl y rental. See the coupons below for details. As a bar association member, you 'II also appreciate our many co nvenie nt airport It'sAvis locations and tim e-saving services that make renting and returning an Avis car fa~Land easy. With an Avis Wizard" Number and an advance reservation. Avis Express• leis you bypass busy ForGreat renta I counters at over 70 U.S. and Canada •t airpo rt locat ions. And du ring peak periods at major airpo rts, ~oving RaJ)id ~eturn" lets.you MemberB ene f I S• depart with a prmted receip t m seconds 1f you are a credit card customer and requ ire no modifications to your rental cha rges. -

Alabama NAACP V Alabama.DCT Opinion

Case 2:16-cv-00731-WKW-SMD Document 181 Filed 02/05/20 Page 1 of 210 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA NORTHERN DIVISION ALABAMA STATE CONFERENCE ) OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION ) FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF ) COLORED PEOPLE, SHERMAN ) NORFLEET, CLARENCE ) MUHAMMAD, CURTIS TRAVIS, ) and JOHN HARRIS, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) CASE NO. 2:16-CV-731-WKW ) [WO] STATE OF ALABAMA and JOHN H. ) MERRILL, in his official capacity as ) Alabama Secretary of State, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION — 4 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE —10 III. BACKGROUND — 11 IV. STANDARD OF REVIEW FOR BENCH TRIALS —19 V. DISCUSSION — 20 A. Section 2 Vote Dilution — 20 1. Section 2: The Statute — 20 Case 2:16-cv-00731-WKW-SMD Document 181 Filed 02/05/20 Page 2 of 210 2. Burden of Proof — 21 3. The Meaning of Section 2 — 23 a. Legislative History — 23 b. Gingles Preconditions and Totality-of-Circumstances Test — 25 4. Section 2 and At-Large Judicial Elections — 29 a. Nipper v. Smith and Later Eleventh Circuit Caselaw Developments — 35 i. The Importance of a State’s Interests — 36 ii. Nipper’s Applicability to Appellate Judicial Elections — 40 iii. The Role of Causation in the § 2 Vote Dilution Analysis — 41 b. Summary — 44 5. Analysis of the Gingles Preconditions — 45 a. Introduction — 45 b. The First Gingles Precondition — 46 i. The Inextricably Intertwined Nature of Liability and Remedy in the Eleventh Circuit — 47 ii. Factors Governing the First Gingles Precondition — 48 iii. Plaintiffs’ Illustrative Plans for Alabama’s Appellate Courts — 54 iv. -

Student Handbook 2013-2014

Student Handbook Fall 2013 Table of Contents Introduction Signature Page ...................................................................................................................................4 First Year Student Class Schedule .....................................................................................................5 New Student Orientation Schedule 2013 ...........................................................................................9 Campus Map ......................................................................................................................................12 Purpose & Philosophy .......................................................................................................................13 Accreditation Statement ....................................................................................................................14 Mission Statement Mission Statement .............................................................................................................................15 Academic Calendar Academic Calendar ...........................................................................................................................16 Orientation Materials Primer on Plagiarism .........................................................................................................................17 What to Expect in Law School ..........................................................................................................20 Setting Your Course & -

PARCA Court Cost Study

PARCA Court Cost Study August 2014 Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama P.O. Box 293931 Birmingham, AL 35229 UNIFIED BUT NOT UNIFORM: JUDICIAL FUNDING ISSUES IN ALABAMA Introduction and Statement of the Case for Reform In 1973, Alabama voters approved a new judicial article in what is widely considered the 20th Century’s most successful effort at overcoming the flaws in Alabama’s 1901 Constitution. Alabama became one of the first states to establish a unified judicial system, replacing what was little more than a collection of local and state courts that preceded it. It is worth remembering what that pre-1973 “system” of judicial administration was like. As originally adopted, Article VI of the Constitution placed the Legislature in primary control of the judicial branch and its development. The Legislature held complete authority to create local courts, subject only to minimum demographic standards. Local and state court funding were completely separate and not even mentioned in the Constitution. While the Supreme Court had conditional authority to establish rules of procedure, its decisions were subject to legislative approval. The result was a very loose, and not very independent, confederation of courts. The Constitution of 1901 did contain a Declaration of Rights that follows standard rules of judicial administration. These include an “open court” provision prohibiting the sale, denial, or delay of justice (Section 13) as well as sections prohibiting excessive fines (Section 15) and imprisonment for debt (Section 20). These provisions remain in the document. The Constitution also contained provisions to control local variations in court procedures. Section 96 prohibited local court costs and charges, stating that any fees must be “applicable to all the counties in the state.” Section 104 prohibited the Legislature from passing special, private, or local laws granting divorces, fixing the punishment for crimes, remitting fines, and regulating the timing of court proceedings or changes of venue. -

Community Preferences and Trial Court Decision-Making: the Influence of Political, Social, and Economic Conditions on Litigation Outcomes" (2011)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Community preferences and trial court decision- making: the influence of political, social, and economic conditions on litigation outcomes Tao Lotus Dumas Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dumas, Tao Lotus, "Community preferences and trial court decision-making: the influence of political, social, and economic conditions on litigation outcomes" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3421. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3421 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. COMMUNITY PREFERENCES AND TRIAL COURT DECISION-MAKING: THE INFLUENCE OF POLITICAL, SOCIAL, AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS ON LITIGATION OUTCOMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Tao Lotus Dumas B.A., Lamar University, 2005 M.A. Louisiana State University, 2009 December 2011 ---“[Juries] will introduce into their verdicts a certain amount--a very large amount, so far as I have observed--of popular prejudice, and thus keep the administration of the law in accord with the wishes and the feelings of the community.” Oliver Wendell Holmes (238, 1920) ii Acknowledgements As anyone who has written a dissertation knows, the lonely hours and emotional struggle of completing the project provide as much of a hurdle as the research itself. -

Alabama Law Institute

Alabama Law Institute REPORT TO THE ALABAMA LEGISLATURE AND INSTITUTE MEMBERSHIP 2020-2021 HONORABLE CAM WARD, PRESIDENT REPORT TO THE ALABAMA LEGISLATURE AND INSTITUTE MEMBERSHIP 2020-2021 Alabama Law Institute The Law Revision Division of Legislative Services Agency www.lsa.state.al.us Alabama State House Law Center Suite 207 Room 326 11 South Union Street P.O. Box 861425 Montgomery, AL 36130 Tuscaloosa, AL 35486 (334) 261-0680 (205) 348-7411 Alabama Law Institute ROOM 326 LAW CENTER SUITE 207, STATE HOUSE TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA PHONE (205) 348-7411 PHONE (334) 261-0680 WWW.LSA.STATE.AL.US FAX (334) 242-8411 February 2021 TO: The Alabama Legislature and Alabama Law Institute Membership It is my pleasure to submit the Alabama Law Institute’s Annual Report to the Alabama Legislature and ALI Membership. The Alabama Law Institute is the official law revision and reform agency for the State of Alabama. Its purpose is to aid the Legislature in proposing and drafting clearer, simpler, and more up-to-date laws. This year, the Legislature will be asked to consider a number of ALI bills that were unable to receive consideration last year due to the 2020 session being cut short by COVID-19. The Business Entities Revisions Act was the singular major piece of ALI legislation that had an opportunity to become law. Therefore, ALI bills on subjects such as government procurement, court costs, subdivisions, non-disparagement obligations, trusts, subdivisions, and child custody will once again be presented. Also, the Business Entities and Trust standing committees of the ALI are proposing some non-substantive, technical changes to the Business Entities Act and the Decanting Act. -

No. 15-14586 United States Court

Case: 15-14586 Date Filed: 07/07/2016 Page: 1 of 33 NO. 15-14586 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT CORY R. MAPLES, Petitioner-Appellant, v. JEFFERSON S. DUNN, COMMISSIONER OF THE ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, Respondent-Appellee. APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA Case No. 5:03-cv-02399-SLB-MHH BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE CONSTITUTION PROJECT IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER CORY R. MAPLES William D. Coston Sarah E. Turberville Martin L. Saad Director, Justice Programs Meaghan H. Kent THE CONSTITUTION PROJECT Christopher S. Crook 1200 18th Street, N.W., Suite 1000 VENABLE LLP Washington, D.C. 20036 575 Seventh Street, N.W. 202-580-6920 (Tel.) Washington, D.C. 20004 202-580-6929 (Fax) 202-344-4000 (Tel.) 202-344-8300 (Fax) Counsel for The Constitution Project July 7, 2016 Case: 15-14586 Date Filed: 07/07/2016 Page: 2 of 33 CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 and 11th Cir. R. 28-1, The Constitution Project hereby states that it is a non-profit organization. The Constitution Project does not have a corporate parent and no publicly traded corporation owns stock in The Constitution Project. Case: 15-14586 Date Filed: 07/07/2016 Page: 3 of 33 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF INTEREST..................................................................................1 STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE.................................................................................5 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................................................................6 -

Rec for Dismissal .Wpd

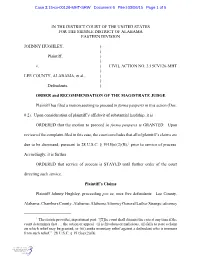

Case 3:15-cv-00126-MHT-SRW Document 6 Filed 03/06/15 Page 1 of 9 IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA EASTERN DIVISION JOHNNY HUGHLEY, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 3:15CV126-MHT ) LEE COUNTY, ALABAMA, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ORDER and RECOMMENDATION OF THE MAGISTRATE JUDGE Plaintiff has filed a motion seeking to proceed in forma pauperis in this action (Doc. # 2). Upon consideration of plaintiff’s affidavit of substantial hardship, it is ORDERED that the motion to proceed in forma pauperis is GRANTED. Upon review of the complaint filed in this case, the court concludes that all of plaintiff’s claims are due to be dismissed, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B),1 prior to service of process. Accordingly, it is further ORDERED that service of process is STAYED until further order of the court directing such service. Plaintiff’s Claims Plaintiff Johnny Hughley, proceeding pro se, sues five defendants: Lee County, Alabama; Chambers County, Alabama; Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange; attorney 1 The statute provides, in pertinent part: “[T]he court shall dismiss the case at any time if the court determines that . the action or appeal– (i) is frivolous or malicious, (ii) fails to state a claim on which relief may be granted; or (iii) seeks monetary relief against a defendant who is immune from such relief.” 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B). Case 3:15-cv-00126-MHT-SRW Document 6 Filed 03/06/15 Page 2 of 9 John Tinney of Roanoke, Alabama; and U.S.