Performing 'Madness' in Major London and Rsc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Cineplex Store

Creative & Production Services, 100 Yonge St., 5th Floor, Toronto ON, M5C 2W1 File: AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920 Publication: Cineplex Mag Trim: 8” x 10.5” Deadline: September 2020 Bleed: 0.125” Safety: 7.5” x 10” Colours: CMYK In Market: September 2020 Notes: Designer: KB A simple conversation plus a tailored plan. Introducing Advice+ is an easier way to create a plan together that keeps you heading in the right direction. Talk to an Advisor about Advice+ today, only from Scotiabank. ® Registered trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920.indd 1 2020-09-17 12:48 PM HOLIDAY 2020 CONTENTS VOLUME 21 #5 ↑ 2021 Movie Preview’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife COVER STORY 16 20 26 31 PLUS HOLIDAY SPECIAL GUY ALL THE 2021 MOVIE GIFT GUIDE We catch up with KING’S MEN PREVIEW Stressed about Canada’s most Writer-director Bring on 2021! It’s going 04 EDITOR’S Holiday gift-giving? lovable action star Matthew Vaughn and to be an epic year of NOTE Relax, whether you’re Ryan Reynolds to find star Ralph Fiennes moviegoing jam-packed shopping online or out how he’s spending tell us about making with 2020 holdovers 06 CLICK! in stores we’ve got his downtime. Hint: their action-packed and exciting new titles. you covered with an It includes spreading spy pic The King’s Man, Here we put the spotlight 12 SPOTLIGHT awesome collection of goodwill and talking a more dramatic on must-see pics like CANADA last-minute presents about next year’s prequel to the super- Top Gun: Maverick, sure to please action-comedy Free Guy fun Kingsman films F9, Black Widow -

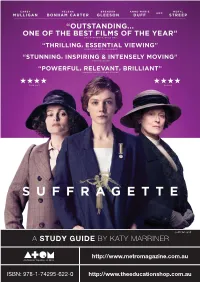

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

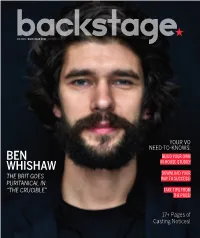

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

NOMINATIONS in 2016 LEADING ACTOR BEN WHISHAW London Spy – BBC Two IDRIS ELBA Luther – BBC One MARK RYLANCE Wolf Hall

NOMINATIONS IN 2016 LEADING ACTOR BEN WHISHAW London Spy – BBC Two IDRIS ELBA Luther – BBC One MARK RYLANCE Wolf Hall – BBC Two STEPHEN GRAHAM This is England ’90 – Channel 4 LEADING ACTRESS CLAIRE FOY Wolf Hall – BBC Two RUTH MADELEY Don’t Take My Baby – BBC Three SHERIDAN SMITH The C Word – BBC One SURANNE JONES Doctor Foster – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTOR ANTON LESSER Wolf Hall – BBC Two CYRIL NRI Cucumber – Channel 4 IAN MCKELLEN The Dresser – BBC Two TOM COURTENAY Unforgotten - ITV SUPPORTING ACTRESS CHANEL CRESSWELL This is England ’90 – Channel 4 ELEANOR WORTHINGTON-COX The Enfield Haunting LESLEY MANVILLE River – BBC One MICHELLE GOMEZ Doctor Who – BBC One ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One LEIGH FRANCIS Celebrity Juice – ITV2 ROMESH RANGANATHAN Asian Provocateur – BBC Three STEPHEN FRY QI – BBC Two FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME MICHAELA COEL Chewing Gum – E4 MIRANDA HART Miranda – BBC One SIAN GIBSON Peter Kay’s Car Share – BBC iPlayer SHARON HORGAN Catastrophe – Channel 4 MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME HUGH BONNEVILLE W1A – BBC Two JAVONE PRINCE The Javone Prince Show – BBC Two PETER KAY Peter Kay’s Car Share –BBC iPlayer TOBY JONES Detectorists – BBC Four House of Fraser British Academy Television Awards – Nominations Page 1 SINGLE DRAMA THE C WORD Susan Hogg, Simon Lewis, Nicole Taylor, Tim Kirkby – BBC Drama Production London/BBC One CYBERBULLY Richard Bond, Ben Chanan, David Lobatto, Leah Cooper – Raw TV/Channel 4 DON’T TAKE MY BABY Jack Thorne, Ben Anthony, Pier Wilkie, -

Royal Shakespeare Company Returns to London's Roundhouse.Pdf

Royal Shakespeare Company returns to London’s Roundhouse from November 2010 with 10 week season • One company of 44 actors playing 228 roles • Six full-scale Shakespeare productions • Two Young People’s Shakespeares – innovative, distilled productions adapted for young people • Education projects across London and at the Roundhouse • One specially constructed 750-seat thrust stage auditorium – bringing audiences closer to the action – in one iconic venue Following its hugely successful, Olivier award-winning Histories Season in 2008, the RSC returns to London’s Roundhouse in November 2010 to present a ten-week repertoire of eight plays by Shakespeare – six full-scale productions and two specially adapted for children and families. This is the first chance London audiences will have to see the RSC’s current 44-strong ensemble, who have been working together in Stratford-upon-Avon since January 2009. The RSC Ensemble is generously supported by The Gatsby Charitable Foundation and The Kovner Foundation. The season opens with Rupert Goold’s production of Romeo and Juliet and runs in repertoire to 5 February next year, with Michael Boyd’s production of Antony and Cleopatra; The Winter’s Tale directed by David Farr; Julius Caesar directed by Lucy Bailey; As You Like It, directed by Michael Boyd; and David Farr’s King Lear (see end of release for production details at a glance). All six productions have been developed throughout their time in the repertoire and are revised and re-rehearsed with each revival in Stratford, Newcastle, London and finally for next year’s residency in New York. The season also includes the RSC’s two recent Young People’s Shakespeare (YPS) productions created especially for children and families, and inspired by the Stand Up For Shakespeare campaign which calls for more children and young people to See Shakespeare Live, Start Shakespeare Earlier and Do Shakespeare on their Feet – Hamlet, directed by Tarell Alvin McCraney, and The Comedy of Errors (in association with Told by an Idiot), directed by Paul Hunter. -

0844 800 1110

www.rsc.org.uk 0844 800 1110 The RSC Ensemble is generously supported by THE GATSBY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION TICKETS and THE KOVNER FOUNDATION from Charles Aitken Joseph Arkley Adam Burton David Carr Brian Doherty Darrell D’Silva This is where the company’s work really begins to cook. By the time we return to Stratford in 2010 these actors will have been working together for over a year, and equipped to bring you a rich repertoire of eight Shakespeare productions as well as our new dramatisation of Morte D’Arthur, directed by Gregory Doran. As last year’s work grows and deepens with the investment of time, so new productions arrive from our exciting new Noma Dumezweni Dyfan Dwyfor Associate Directors David Farr and Rupert Goold, who open the Phillip Edgerley Christine Entwisle season with King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. Later, our new Artistic Associate Kathryn Hunter plays her first Shakespearean title role with the RSC in my production of Antony and Cleopatra, and we follow the success of our Young People’s The Comedy of Errors with a Hamlet conceived and directed by our award winning playwright in residence, Tarell Alvin McCraney. I hope that you will come and see our work as we continue to explore just how potent a long term community of wonderfully talented artists can be. Michael Boyd Artistic Director Geoffrey Freshwater James Gale Mariah Gale Gruffudd Glyn Paul Hamilton Greg Hicks James Howard Kathryn Hunter Kelly Hunter Ansu Kabia Tunji Kasim Richard Katz Debbie Korley John Mackay Forbes Masson Sandy Neilson Jonjo O’Neill Dharmesh Patel Peter Peverley Patrick Romer David Rubin Sophie Russell Oliver Ryan Simone Saunders Peter Shorey Clarence Smith Katy Stephens James Traherne Sam Troughton James Tucker Larrington Walker Kirsty Woodward Hannah Young Samantha Young TOPPLED BY PRIDE AND STRIPPED OF ALL STATUS, King Lear heads into the wilderness with a fool and a madman for company. -

I Can't Recall As Exciting a Revival Sincezeffirelli Stunned Us with His

Royal Shakespeare Company The Courtyard Theatre Southern Lane Stratford-upon-Avon Warwickshire CV37 6BB Tel: +44 1789 296655 Fax: +44 1789 294810 www.rsc.org.uk ★★★★★ Zeffirelli stunned us with his verismo in1960 uswithhisverismo stunned Zeffirelli since arevival asexciting recall I can’t The Guardian on Romeo andJuliet 2009/2010 134th report Chairman’s report 3 of the Board Artistic Director’s report 4 To be submitted to the Annual Executive Director’s report 7 General Meeting of the Governors convened for Friday 10 September 2010. To the Governors of the Voices 8 – 27 Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon, notice is hereby given that the Annual Review of the decade 28 – 31 General Meeting of the Governors will be held in The Courtyard Transforming our Theatres 32 – 35 Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 10 September 2010 commencing at 4.00pm, to Finance Director’s report 36 – 41 consider the report of the Board and the Statement of Financial Activities and the Balance Sheet Summary accounts 42 – 43 of the Corporation at 31 March 2010, to elect the Board for the Supporting our work 44 – 45 ensuing year, and to transact such business as may be transacted at the Annual General Meetings of Year in performance 46 – 49 the Royal Shakespeare Company. By order of the Board Acting companies 50 – 51 The Company 52 – 53 Vikki Heywood Secretary to the Governors Corporate Governance 54 Associate Artists/Advisors 55 Constitution 57 Front cover: Sam Troughton and Mariah Gale in Romeo and Juliet Making prop chairs at our workshops in Stratford-upon-Avon Photo: Ellie Kurttz Great work • Extending reach • Strong business performance • Long term investment in our home • Inspiring our audiences • first Shakespearean rank Shakespearean first Hicks tobeanactorinthe Greg Proves Chairman’s Report A belief in the power of collaboration has always been at the heart of the Royal Shakespeare Company. -

Shakespeare Newsletter

Do you have five minutes, even three? That’s all you need to read one article in this newsletter. If you like it, there’s more, read on. If ways that Bill still matters not, well you get the idea what we’re up to here. an occasional newsletter, Fall 2012 Incorporating Friends into Shakespeare By Blair Warner Shakespeare. The greatest playwright ever, whom many fear, including myself. But I am here to tell you that Bill is not so bad. Reading Shakespeare is less dif- ficult if you think of the plays as people you know. Not the plays, of course, but the characters in the plays. Just envision people that you know as you read the scenes—pretend they are the ones on stage. It might sound silly, but it really helped me while reading Taming of the Shrew. I imagined one of my close friends Ashley playing the role of Bianca and her younger sister Nicole playing the role of Katherina. Both sisters have personalities that can be compared to the two sisters in the play. Ashley, who is soft-spoken at times, is very nice and peaceful, like Bianca. She gets along with everyone that she meets. Nicole is much more like Katherina. She is strong-willed, says whatever happens to be on her mind, and at times can be angry. People tend to be intimidated by her mannerisms. Just like Kate in Taming. Imagining the similarities between these pairs of sisters as I read made me laugh at times, enjoying Taming more and more as I read. -

PARTICIPATION and COOPERATION in ARTS EDUCATION « ELTE TERMÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KAR BUDAPEST in Focus: Drama and Theatre Education

| | » PARTICIPATION AND COOPERATION IN ARTS EDUCATION « ELTE TERMÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KAR BUDAPEST in focus: Drama and Theatre Education BOOK OF PROCEEDINGS SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME COMMITTEE Gábor BODNÁR, ELTE University, Faculty of Humanities, Music Department Andrea KÁRPÁTI, MTA-ELTE Visual Culture Research Group and Corvinus University of Budapest Katalin KISMARTONY, ELTE University, Faculty of Primary and Early Childhood Education, Department of Classroom Music Virág KISS, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education, Eszterházy Károly University Nedda KOLOSAI, ELTE University, Faculty of Primary and Early Childhood Education, Department of Education Géza Máté NOVÁK, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education, Conference Chair László TRENCSÉNYI, ELTE University, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Institute of Education ORGANISING COMMITTEE Tibor DARVAI, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Tímea JUHÁSZ, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Virág KISS, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education EDITOR Mária LOSONCZ, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Patrick MULLOWNEY, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Géza Máté NOVÁK Krausz Éva PÓTHNÉ, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Katalin SÁNDOR, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education REVIEWERS Gyula SZAFFNER, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Gábor BODNÁR Katalin TAMÁS, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education Emil GAUL -

TEACHING SHAKESPEARE 12 Summer 2017 TEACHING SHAKESPEARE in HANOI

ISSUE 12 FIRST EVER ðSUMMERð ISSUE POLICY • PEDAGOGY • PRACTICE Summer 2017 ISSN 2049-3568 (Print) • ISSN 2049-3576 (Online) TAILOR TEACHING TO ASD STUDENTS WITH SUSIE FLINTHAM AND CHARLOTTE ROBERTS TALK BACK TO OTHELLO WITH AMY SMITH, HER STUDENTS AND JUVENILE OFFENDERS TOUR THE FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY PROMPT BOOKS WITH ADAM MATTHEW Find this magazine and more at the BSA Education Network’s webpage www.britishshakespeare.ws/education/ NOTICEBOARD Photograph © Claudio Divizia / Shutterstock.com © Photograph THE BSA CONFERENCE The BSA is proud to announce the locations, institutional partners and themes of its next three conferences: • SHAKESPEARE STUDIES TODAY 14–17 June 2018, Queen’s University, Belfast • SHAKESPEARE: RACE AND NATION July 2019, Swansea University • SHAKESPEARE IN ACTION July 2020, University of Surrey The BSA conference is the largest regular Shakespeare conference in the United Kingdom, bringing together researchers, teachers, and theatre practitioners from all SHARE YOUR VIEWS over the world to share the latest work on Shakespeare With Teaching Shakespeare now firmly in double figures, and his contemporaries. From 2018, the BSA conference we thought this would be a good time to check in with our will become an annual event, having previously been held readers and ask for your views on and experiences with us. every two years. The BSA is delighted that high demand A ten-question survey which should take no more than ten has enabled us to increase the frequency of this, our minutes of your time to answer, to help us serve the BSA flagship event. BSA conferences include a wide range community even better, can be found at: of sessions and events, including academic lectures by www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/JRDLVHL internationally renowned Shakespeare critics, talks by celebrated practitioners and practical workshops. -

The Theatre Royal Bristol

.. THE THEATRE ROYAL BRISTOL DECLINE AND REBIRTH 1834-1943 KATHLEEN BARKER, M.A. ISSUED BY 11HE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE IDSTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE UNIVERSITY, BRISTOL Price Two Shillings and Six Pence Prmted by F. Bailey & Son I.Jtd., Du.rsley, Glos. 1966 � J- l (-{ :J) BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE THEATRE ROYAL, BRISTOL LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS DECLINE AND REBIRTH (1834 - 1943) Hon. General Editor: PATRICK McGRATH Assistant General Editor: PETER HARRIS by Kathleen Barker, M.A. The Theatre Royal, Bristol: Decline and Rebirth (1834-1943) is The Victorian age is not one on which the theatre historian the fourteenth in a series of pamphlets issued by the Bristol Branch looks back with any great pleasure, although it is one of consider of the Historical Association through its standing Committee able interest. The London theatrical scene was initially dominated on Local History (Hon. Secretary. Miss Ilfra Pidgeon). In an earlier by the two great Patent theatres of Covent Garden and Drury pamphlet. first published in 1961, Miss Barker dealt with the Lane, both. rebuilt on a scale too large to suit "legitimate" drama. history of the Theatre Royal during the first seventy years of its Around them had sprung up a myriad Minor Theatres, legally existence. Her work attracted great interest. and a second edition able only to offer spectacle and burletta: a character in which they was published in 1963. She now brings up to modem times the were too well established for the passing of the Act for Regulating largely untold and fascinating story of the oldest provincial theatre the Theatres, which ended the monopoly of the Patent theatres in with a continuous working history.