Literary Reviews - 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Béal an Átha Móir Co

Béal an Átha Móir Co. Leitrim, Ireland the heart of hidden Ireland www.ballinamore.ie BALLINAMORE WELCOME TO BALLINAMORE …the Heart of Hidden Ireland, ideally located in an area steeped in history, natural beauty and culture. Ballinamore makes a great touring base for a range of interesting outings. Sample some of the constantly changing landscape through walking and cycling tours or spend the day fishing in one of many premier fishing locations. Discover your family history, view historical items or learn more about some of our famous local ancestors at the Leitrim Genealogy Centre. Arts, crafts and music are a specialty as the area is home to many artists and craftspeople, studios and galleries. Enjoy family time at impressive activity parks and tourist areas. The options are more varied than you might imagine. Ballinamore offers a variety of accommodation and dining to suit all budgets. So come and let us exceed your expectations! www.Ballinamore.ie The abundance of natural reserves in and around Ballinamore make it the perfect place for your outdoor adventures. Fishing Ballinamore is widely acknowledged as an angler’s paradise - with 28 lakes within a 5 mile radius and some 17km of riverbank, Ballinamore has hosted numerous national and international angling competitions. The area is also a premier location for game and coarse fishing and has some of the cleanest and most lightly fished fresh waters in Europe. Access to the waters is well developed with fishing stands, stiles, lakeshore drives, and car parks. Boats, detailed maps and bait stocklists are locally available. Forge Tackle Shop, Tel: 071-9644051. -

The Novel and the Short Story in Ireland

The Novel and the Short Story in Ireland: Readership, Society and Fiction, 1922-1965. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Anthony Halpen April 2016 Anthony Halpen Institute of Irish Studies The University of Liverpool 27.03.2016 i ABSTRACT The Novel and the Short Story in Ireland: Readership, Society and Fiction, 1922-1965. Anthony Halpen, The Institute of Irish Studies, The University of Liverpool. This thesis considers the novel and the short story in the decades following the achievement of Irish independence from Britain in 1922. During these years, many Irish practitioners of the short story achieved both national and international acclaim, such that 'the Irish Short Story' was recognised as virtually a discrete genre. Writers and critics debated why Irish fiction-writers could have such success in the short story, but not similar success with their novels. Henry James had noticed a similar situation in the United States of America in the early nineteenth century. James decided the problem was that America's society was still forming - that the society was too 'thin' to support successful novel-writing. Irish writers and critics applied his arguments to the newly-independent Ireland, concluding that Irish society was indeed the explanation. Irish society was depicted as so unstructured and fragmented that it was inimical to the novel but nurtured the short story. Ireland was described variously: "broken and insecure" (Colm Tóibín), "often bigoted, cowardly, philistine and spiritually crippled" (John McGahern) and marked by "inward-looking stagnation" (Dermot Bolger). -

John Mcgahern : His Time and His Places

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Articles School of Business and Humanities 2016 John McGahern : his Time and his Places Eamon Maher Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Paul Butler [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ittbus Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Maher, E. & Butler, P. (2016) John McGahern : his Time and his Places, Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 39, no. 2 (2016), pp.27-54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Business and Humanities at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License A Treasury of Resources Eamon Maher and Paul Butler John McGahern: His Time and His Places John McGahern was a writer who always demonstrated a keen sense of place. Readers of his fiction inevitably note strong similarities between the figures and landscapes it evokes and the people and places the writer knew in real life. He was acutely aware of how important it was to write from personal knowledge, from everyday experience, in order to capture the beauty that can be found in the ordinary experiences of people going about their daily lives in small rural communities, mostly located in the Leitrim/Roscommon area where McGahern spent the majority of his life. His characters and settings are at times painfully real, whether it be the stoical Elizabeth Reegan in The Barracks (1963), who, on the threshold of a painful death from cancer, really “sees” the beauty of nature for the first time; or the uncertain groping towards adulthood of young Mahoney in The Dark (1965); the tyrannical actions of the patriarch Moran in Amongst Women (1990); or the unrelenting womanizing John Quinn in That They May Face the Rising Sun (2002). -

Leitrim County Development Plan 2022-2028 Strategic Issues Paper

LLeeiittrriimm CCoouunnttyy DDeevveellooppmmeenntt PPllaann 22002222--22002288 SSttrraatteeggiicc IIssssuueess PPaappeerr Preparation of new Leitrim County Development Plan Strategic Issues Paper TABLE OF CONTENTS 8.2 Public Rights-Of-Way ........................................................ 21 8.3 Green Infrastructure ........................................................ 21 1. Introduction ............................................................................... 3 9. Heritage .................................................................................... 22 2. Leitrim’s Vision ........................................................................... 4 9.1 Leitrim Heritage Plan 2020-2025 ..................................... 22 3. Strategic Planning – What has happened since the last County 9.2 Built Heritage ................................................................... 23 Development Plan? ............................................................................ 6 9.3 Natural Heritage ............................................................... 23 3.1 Project Ireland 2040: National Planning Framework ......... 6 9.4 Views and Prospects ........................................................ 23 3.2 Regional Spatial and Economic Strategy for the Northern 9.5 Cultural Heritage .............................................................. 24 and Western Region....................................................................... 6 10. Regeneration and Placemaking ........................................... -

Anglo-Irish “Distortion”: Double Exposure in Francis Bacon’S Portraits and Beckett’S the Old Tune

Anglo-Irish “Distortion”: Double Exposure in Francis Bacon’s Portraits and Beckett’s The Old Tune David Clare New Hibernia Review, Volume 22, Number 1, Spring/Earrach 2018, pp. 102-119 (Article) Published by Center for Irish Studies at the University of St. Thomas DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/nhr.2018.0007 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/699174 Access provided by University of Limerick (10 Oct 2018 14:57 GMT) David Clare • Anglo-Irish “Distortion”: Double Exposure in Francis Bacon’s Portraits and Beckett’s The Old Tune Many critics—most notably Michael Billington, James Knowlson, Jane A lison Hale, Erik Tonning, and Peter Fifield—have discussed the painter Francis Bacon’s probable influence on the visual images in Samuel Beckett’s work for the stage, particularly the disembodied mouth in the 1972 play Not I.1 This, however, is not the only way in which the work of these two artists is connected. Both men, each from an Anglican family residing in Leinster, shared an interest in depicting their exile from Ireland by superimposing two images on top of one another in their work.2 Bacon depicted the “fragmentation of self” that results from exile by superimposing two faces on one another in his portraits.3 “Distor- tion, or contortion, in Bacon’s pictures sometimes occurs by his superimposing one image on another,” and the resulting obscured faces, especially those in his 1. See: Michael Billington, One Night Stand: A Critic’s View of Modern British Theatre (London: Nick Hern Books, 2002), 23; James Knowlson, Images of Beckett (Cambridge: Cambridge Univer- sity Press, 2003), 83; Jane Alison Hale, “The Impossible Art of Francis Bacon and Samuel Beckett,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 111 (1988), 268–74; Erik Tonning, Samuel Beckett’s Abstract Drama: Works for Stage and Screen 1962–1985 (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2007), 120; Peter Fifield, “Gaping Mouths and Bulging Bodies: Beckett and Francis Bacon,” Journal of Beckett Studies 1–2 (September, 2009), 57–71. -

Remembered Light: Constants in the Fiction of John Mcgahern

Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 5 (1992): 93-105 Remembered Light: Constants in the Fiction of John McGahern Brian Hughes University of Alicante Art is, after the failure of love, an attempt to créate a world in which we might be able to Uve: maybe that world wouldn't last very long; it probably wouldn't last for ever; but it would be a world of the imagination over which we might rule ... We cannot live, we can only rule, although we have no reason and no right to rule, except our own instinctive need. Thus we rule in the illusory permanence of our false gods. (John NfGahern)1 For a people long condemned to labour on the earth for their subsistence, the Irish are unusually apt to view the human body with contempt, in the light of a potential corpse rather than as a living source of pride and pleasure. To see in this the effect of a strict strain of Catholicism on a subdued northern people is to overlook both the Celtic reputation for wildness and the fact that some of the most thoroughgoing revilers of the flesh in the canon of world literature are Irish Protestants. The greatest of the mortifiers of the body and deniers of its privileges is, of course, the Anglican cleric Swift, the satirist who noticed that fundamentalist inspiration derived both logically and etymologically from wind issuing from the fundament, the inventor of the trade in Yahoo hide and the fascinated observer of the considerable difference flaying made to the back of a Dublin whore. -

Introducing John Mcgahern

INTRODUCING JOHN MCGAHERN Art is an attempt to create a world in which we can live: if not for long or forever, still a world of the imagination over which we can reign, and by reign I mean to reflect purely on our situation through this created world of ours, this Medusa’s mirror, allowing us to see and to celebrate even the totally intolerable. John McGahern It seems appropriate to allow John McGahern himself to begin this brief account of his life and work with his own views on the role of art, for few other writers have managed to realise as effectively the realities of their life experience in literature, or as Denis Sampson has written "to sift through the familiar material and the established fictional modes in order to "see" the essence of his own experience in his given place and time that the ordinary life of farmers and policemen and teachers become the exotic, the mysterious. Born in Dublin in 1934 McGahern grew up in Ballinamore county Leitrim and Cootehall, county Roscommon. While his early years were spent with his mother, a national school teacher in Ballinamore, McGahern was raised by his father, who was sergeant of Cootehall Garda station, after his mother’s death in 1945. He was educated at the Presentation Brothers college in Carrick-on- Shannon before attending St. Patrick’s teacher training college in Drumcondra where he graduated in 1954. He began teaching the following year at the highly regarded St. John the Baptist Boys National school in Clontarf. In 1957 he graduated with a BA from University College Dublin. -

Spring 2015 13

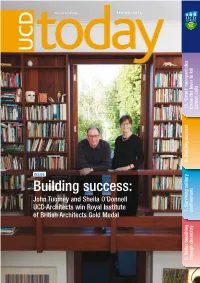

www.ucd.ie/ucdtoday SPRING 2015 13. ‘Smart’ nanoparticles the lever to kill throw cancer cells 9. Building success INSIDE Building success: John Tuomey and Sheila O’Donnell UCD Architects win Royal Institute 7. Surviving solitary confinement of British Architects Gold Medal 5. Better breathing through chemistry Contents Features Better breathing Surviving solitary Building success ‘Smart’ 5 through 7 confinement 9 13 nanoparticles chemistry throw the lever to kill cancer cells Students want to wait To those of us involved in student recruitment activities, this year’s CAO first preferences are no surprise. Overall, our first preferences are down – from 9,218 to 8,856 but this 2015 figure still exceeds every other previous year and UCD retains its position as university of first choice among applicants by a considerable margin. In general, the UCD figures follow the national trends: up in business, law, economics, architecture and engineering; down in science, agriculture, physiotherapy and nursing. The upward trend in science and agriculture over the previous EILIS O’BRIEN eight years has been meteoric. Arts and medicine have not fared so well, Director of Communication for different reasons. and Marketing Certainly, the reduction in entry routes to our degrees – down from 86 to 43 (not including mature and graduate entry), has not seen a corresponding fall in first preferences and the recent announcement by Maynooth University that it will reduce entry codes to 20 will reinforce the argument that students don’t need to select narrow disciplines before they even leave school. Far better for the majority of students to specialise later in their studies, when they have experienced various subjects and disciplines. -

John Mcgahern, Post-Revival Literature, and Irish Cultural Criticism

John McGahern, Post-Revival Literature, and Irish Cultural Criticism Stanley van der Ziel New Hibernia Review, Volume 21, Number 1, Spring/Earrach 2017, pp. 123-142 (Article) Published by Center for Irish Studies at the University of St. Thomas DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/nhr.2017.0008 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/660982 Access provided by Maynooth University (19 Dec 2017 18:57 GMT) Stanley van der Ziel John McGahern, Post-Revival Literature, and Irish Cultural Criticism John McGahern’s attitude to many Irish writers from the first half of the twen- tieth century was often ambivalent. He instinctively disliked and distrusted the overt polemical stance adopted by many writers in the decades immediately fol- lowing Independence, even if he could find in those same writers qualities of style or vision that he admired and, on occasion, even echoed in his own fiction. His relationship with the poet Patrick Kavanagh is a case in point. As early as 1959 he wrote to Michael McLaverty that, “Kavanagh is an irresponsible critic and a careless poet. It is a pity he doesn’t take more care with his poems because he is richly gifted.”1 On the one hand, McGahern deplored Kavanagh’s part in the brash literary culture that existed in Dublin in the 1940s and 1950s. He later im- mortalized his youthful experience, both of being subjected to what he described in an autobiographical essay from the 1990s as “the doubtful joy of Kavanagh’s company,” and of the general atmosphere of that imaginatively and intellectually stifling Dublin-bohemian milieu, by re-imagining it in his fiction.2 Such stories about rural drifters in the Hibernian metropolis as “My Love, My Umbrella” and “Bank Holiday” draw on the future novelist’s youthful experiences of literary coteries in Dublin during his twenties, as does the brilliant satire on midcentury Dublin literary culture that is The Pornographer (1979). -

'A Big, Bad Word': Sex, Dissent and the Fiction of John Mcgahern

‘A big, bad word’: Sex, dissent and the fiction of John McGahern Frank Shovlin In 1963 sexual intercourse began, or so Philip Larkin would have it. The Beatles had come out of their Liverpool cavern to begin world conquest, the masses could feast on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the sixties were swinging. All the old trussed-up morality could be abandoned, and, for a dedicated misanthrope like Larkin, the role of voyeur ended up balanced painfully somewhere between jealousy and disgust: When I see a couple of kids And guess he’s fucking her and she’s Taking pills or wearing a diaphragm, I know this is paradise Everyone old has dreamed of all their lives—1 In May 1965, two years after this annus mirabilis, Larkin’s publisher, Faber and Faber, brought to the bookshops a novel called The Dark, which, in its frank and brutal depiction of one Irish boy’s sexual awakening, made D. H. Lawrence look like a Mills and Boon offcut. The Dark was the second book from the pen of Faber’s new bright young thing of Irish writing, John McGahern, then just thirty years of age and a great admirer of Hull’s hermetical librarian. McGahern, from the moment he began reading Larkin till the end of his life, was an unstinting devotee of the English poet’s art.2 Partly it was Larkin’s very straight and ordered view of the world that appealed to McGahern, and partly his acid commentaries on the stupidity of most human congress, particularly on the potentially destructive or numbing force of romance and marriage. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: “WE HAVE COME of AGE”: GROWING BODIES in the TWENTIETH-CENTURY IRISH NOVEL Kelly Jayne Steen

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: “WE HAVE COME OF AGE”: GROWING BODIES IN THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY IRISH NOVEL Kelly Jayne Steenholdt McGovern, Ph.D. 2012 Directed by: Professor Brian Richardson, Department of English Twentieth-century Irish culture — shaped by, for instance, the Catholic Church, nationalist narratives of blood sacrifice for “Mother Ireland,” and the experience of emergence from colonialism—put special pressure on the meanings attached to bodies in narratives of both individual and national maturation. This dissertation examines the human body’s role in Irish novels of development, tracing specifically how Irish authors deploy the growing body in relation to the self-cultivating subject of a Bildungsroman (or “coming of age” novel). This project shows that Irish social conditions provoked urgent reworkings of generic conventions, and impelled Irish authors to develop sophisticated strategies for representing growing bodies in narrative. Through close examinations of four novels, this project identifies four facets of the role the growing body can take in fictions of development. The introduction provides an overview of the absent body, the body that grows in passing, the body growing sideways, and the unnarratable body. Individual chapters examine these respective facets as they manifest in James Joyce’s highly influential Portrait of the Artist as a Y oung Man (1916), John McGahern’s The Dark (1965), Éilís Ní Dhuibhne’s The Dancers Dancing (1999), and Anne Enright’s The Wig My Father Wore (1995). Chapter one describes how Joyce largely reserves Stephen Dedalus’s body from representation so that other developmental aspects feature more prominently. Chapter two examines McGahern’s representations of the real, material growing body’s volatility and entanglement with forces beyond the subject’s autonomous control as a strategic response to the post-Independence Irish social environment. -

View: Journal of Flann O’Brien Studies 1.1

Report 100 Myles: The International Flann O’Brien Centenary Conference Vienna Centre for Irish Studies, 24–27 July 2011. Erika Mihálycsa Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj Having occupied my seat in a shady room of the Centre for Irish Studies at the University of Vienna, among a throng of high-spirited Flanneurs on the morning of 25 July 2011, I reflected on the subject of our common full-time paraliterary activities. One beginning and one ending for a literary conference was a thing I could not agree with. A Flann O’Brien conference worth its salt may have three openings entirely dissimilar and, for that matter, a hundred times as many endings. Example of an opening, first: Werner Huber (University of Vienna), host and co- organiser introduced us to the DeSelbian (dis)connections between the city of Vienna and a smallish man called Brian O’Nolan, whom the world reveres under the twin names Flann O’Brien/Myles na gCopaleen. He guided us around the premises – which appropriately included the nearby Narrenturm, continental Europe’s oldest building for the accommodation of mental patients – through very reverend figures of Irish history, such as the Field Marshal O’Donnell, who saved the life of the emperor Franz Josef; Oliver St John Gogarty (aka Buck Mulligan), a medical student who in 1907 learned the subtleties of surgical savagery on this very campus; and a cockshy young man by the name of Samuel Beckett, who pined after a cousin of the female sex being initiated in the art of dancing at the nearby Schloss Hellerau-Laxenburg (where group activities included naked sun-bathing, to the major delight of god-fearing Austrian Bürgers).