Competition in Licensing Music Public Performance Rights Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Copyright by Ashley N. Mack 2013

Copyright by Ashley N. Mack 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Ashley N. Mack Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: DISCIPLINING MOMMY: RHETORICS OF REPRODUCTION IN CONTEMPORARY MATERNITY CULTURE Committee: Dana L. Cloud, Supervisor Joshua Gunn Barry Brummett Sharon J. Hardesty Christine Williams DISCIPLINING MOMMY: RHETORICS OF REPRODUCTION IN CONTEMPORARY MATERNITY CULTURE by Ashley N. Mack, B.A.; B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2013 Dedication To Tiffany—for being an awesome lady, thinker, worker, “true” sister, daughter, and mother. Acknowledgements My family has something of a “curse”: Multiple generations of women have been single, working mothers. Therefore, the social pressures, expectations and norms of motherhood have always permeated my experiences of reproduction and labor. Everything I do has been built on the backs of the women in my family—so it is important that I thank them first and foremost. I would be remised if I did not also specifically thank my big sister, Tiffany, for sharing her experiences as a mother with me. Hearing her stories inspired me to look closer at rhetorics of maternity and this project would not exist if she were not brave enough to speak up about issues that produce shame and fear for many moms. Dana Cloud, my advisor, is a shining light at the end of the many dark tunnels that academic work can produce. -

Winter Arrives with a Wallop

weather Monday: Showers, high 42 degrees monday Tuesday: Partly cloudy, high 42 degrees Wednesday: Rain likely, high in the low 40s THE ARGO Thursday: Rain likely , high in the upper 30s Volume 58 Friday: Chance of rain , high in the low 30s of the Richard Stockton College Number 1 Serving the college community since 1973 m ihh Winter arrives with a wallop Dan G rote ed to engage in snowball fights The Argo despite or perhaps in spite of the decree handed down by the Much like the previous semes- Office of Housing and ter, when Hurricane Floyd barked Residential Life, which stated at Stockton, the new semester has that snowball fighters can expect begun with weather-related can- a one hundred dollar fine and loss cellations. In the past two weeks, of housing. four days of classes have seen One freshman, Bob Atkisson, cancellations, delayed openings, expressed his outrage at the and early closings. imposed rule. "I didn't think we Snowplows have crisscrossed should get fined for throwing the campus, attempting to keep snowballs. I went to LaSalle a the roads clear, while at the same couple days ago, and they actual- time blocking in the cars of resi- ly scheduled snowball fights dents, some of whom didn't real- there." ly seem to mind. Though many students were Optimistic students glued heard grumbling over having to themselves to channel 2 in hopes dig their cars out of the snow due of not having to go to their 8:30 to the plowing, they acknowl- classes, while others called the edged that plant management did campus hotline (extension 1776) an excellent job keeping for word of the same. -

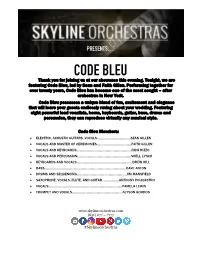

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC Competition for Young Professionals

9th INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC competition for Young Professionals SATURDAY | APRIL 10 | 2021 PROGRAM Dior Quartet Joseph Haydn—Quartet Op. 76 No. 3 “Emperor” IV. Finale: Presto Welcome to Chesapeake Music’s 9th International Caroline Shaw—Blueprint Christos Hatzis—Quartet No. 2 “The Gathering” Chamber Music Competition and while the world-wide III. Nadir health crisis makes it necessary to hold this event virtually, I Anton Dvorak—Quartet No. 13 in G Major, Op. 106 am confident you will be rewarded with a day of outstanding II. Adagio ma non troppo performances highlighted by musical skill and youthful Dmitri Shostakovich—Quartet No. 9, Op. 117 enthusiasm. V. Allegro This biennial event began nineteen years ago when a group of local music lovers resolved to create a way to encourage and AYA Piano Trio support young musicians in their efforts to build careers. This Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart—Piano Trio in C Major K. 54 vision has been fulfilled as many of the ensembles have become I. Allegro well known in the concert world and all of the participants gain Felix Mendelssohn—Piano Trio in C Major, Op. 66 valuable insights from our judges. I. Allegro energico e con fuaco I am amazed and enormously grateful for the effort put Maurice Ravel—Piano Trio in A minor forth by our Competition Committee. Every other year these I. Modéré volunteers take on the challenge of producing this major II. Pantoum, Assez vif musical competition and then last year the event was cancelled Dimitri Shostakovich—Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor just days before it was to go on. -

American Idol S3 Judge Audition Venue Announcement 2019

Aug. 5, 2019 TELEVISION’S ICONIC STAR-MAKER ‘AMERICAN IDOL’ HITS THE RIGHT NOTES LUKE BRYAN, KATY PERRY AND LIONEL RICHIE TO RETURN FOR NEW SEASON ON ABC Twenty-two City Cross-Country Audition Tour Kicked Off on Tuesday, JuLy 23, in BrookLyn, New York Bobby Bones to Return as In-House Mentor In its second season on ABC, “American Idol” dominated Sunday nights and claimed the position as Sunday’s No. 1 most social show. In doing so, the reality competition series also proved that untapped talent from coast to coast is still waiting to be discovered. As previously announced, the star-maker will continue to help young singers realize their dreams with an all-new season premiering spring 2020. Returning to help find the next singing sensation are music industry legends and all-star judges Luke Bryan, Katy Perry and Lionel Richie. Multimedia personality Bobby Bones will return as in-house mentor. The all-new nationwide search for the next superstar kicked off with open call auditions in Brooklyn, New York, and will advance on to 21 additional cities across the country. In addition to auditioning in person, hopefuls can also submit audition videos online or show off their talent via Instagram, Facebook or Twitter using the hashtag #TheNextIdol. “‘American Idol’ is the original music competition series,” said Karey Burke, president, ABC Entertainment. “It was the first of its kind to take everyday singers and catapult them into superstardom, launching the careers of so many amazing artists. We couldn’t be more excited for Katy, Luke, Lionel and Bobby to continue in their roles as ‘American Idol’ searches for the next great music star, with more live episodes and exciting, new creative elements coming this season.” “We are delighted to have our judges Katy, Luke and Lionel as well as in-house mentor Bobby back on ‘American Idol,’” said executive producer and showrunner Trish Kinane. -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

Rock Star Bon Jovi Washes Dishes to Keep His Community

Rock Star Bon Jovi Washes Dishes to Keep His Community Fed Week of July 19, 2020 In the News Had this been a normal summer, rock superstar Jon Bon Jovi, 58, would be on tour with his rock band Bon Jovi, but the global pandemic put the kibosh on that. So instead, Bon Jovi -- the man, not the band -- filled in as a dishwasher at the JBJ Soul Kitchen, a nonprofit community restaurant in New Jersey operated by the Jon Bon Jovi Soul Foundation. And one outcome of that is a new song he wrote with help from his fans to tell their stories of life during the shutdown. The song is called "If You Can't Do What You Do, You Do What You Can." The JBJ Soul Kitchen, now in operation in three New Jersey locations, is an effort to address food insecurity -- hunger -- among people in need. The menu, which features fresh farm-to-table meals, has no posted prices. Patrons who can afford to do so make a donation to cover their own meal and the meal of someone else. Individuals or families who cannot afford to donate are fed anyway, and those who are able can pay it forward by volunteering for tasks in the kitchen, such as washing dishes. The JBJ Soul Kitchen website expresses the philosophy this way: "Community Dining with Dignity. All are welcome at our table where locally sourced ingredients, dignity and respect are always on the menu." The required increased social distancing ordered during the pandemic upended the Soul Kitchen's normal practices, especially when meals could only be served by take-out and the public could not be allowed in the kitchen, so Bon Jovi filled in at one of the restaurant's locations as a dishwasher. -

Songwriter Symposium

The Texas Songwriters Association Presents 15th Annual SONGWRITER SYMPOSIUM JANUARY 9 – 13, 20 Holiday Inn Midtown Austin, Texas www.austinsongwritersgroup.com ASG SONGWRITER SYMPOSIUM 2019 SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 9, 2019 5:00 – 6:30 PM Symposium Registration (Magnolia Room) Walk Up Registration & Pre-Registration Check In: 1. Pick Up Schedule and Wrist Bands 2. Sign Up for the One-On-One with Publisher of Your Choice 3. Sign Up for the One-On-Ones with the music industry professionals ( writers, publicists, lawyers, producers, performance coach, etc. ) 4. Sign up for showcases 6:30 PM: Kick Off Party Meet and Greet! 7:00 – 8:00 PM: Open Mic In The Round 8:00 – 9:15 PM PUBLISHERS PANEL Music Publishers Bobby Rymer, Jimmy Metts, Sherrill Dean Blackman, Steve Bloch, and Antoinette Olesen kick off Symposium 2019 by leading this panel discussing current trends in music publishing. 7:00 – 8:00 PM: Open Mic In The Round 10:00 PM - Midnight SONG PICKING CIRCLES After the Music Publishing Panel, grab your instruments and circle for the opening night song picking circles. THURSDAY, JANUARY 10, 2019 9:00 AM Symposium Registration (Magnolia Room) Walk Up Registration & Pre-Registration Check In: 1. Pick Up Schedule and Wrist Bands 2. Sign Up for the One-On-One with Publisher of Your Choice 3. Sign Up for the One-On-Ones with the music industry professionals ( writers, publicists, lawyers, producers, performance coach, etc. ) 4. Sign up for showcases PUBLISHERS PANEL (HILL COUNTRY BALL ROOM) This is an introduction to the publishers. They will tell you a little about themselves, and some of the things they are currently working on. -

Finding Grace in the Concert Hall: Community and Meaning Among Springsteen Fans

FINDING GRACE IN THE CONCERT HALL: COMMUNITY AND MEANING AMONG SPRINGSTEEN FANS By LINDA RANDALL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY On Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Religion December 2008 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Lynn Neal, PhD. Advisor _____________________________ Examining Committee: Jeanne Simonelli, Ph.D. Chair _____________________________ LeRhonda S. Manigault, Ph.D _____________________________ ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, my thanks go out to Drs. Neal and Simonelli for encouraging me to follow my passion and my heart. Dr. Neal helped me realize a framework within which I could explore my interests, and Dr. Simonelli kept my spirits alive so I could nurse the project along. My concert-going partner in crime, cruisin’tobruce, also deserves my gratitude, sharing expenses and experiences with me all over the eastern seaboard as well as some mid-America excursions. She tolerated me well, right up until the last time I forgot the tickets. I also must recognize the persistent assistance I received from my pal and companion Zero, my Maine Coon cat, who spent hours hanging over my keyboard as I typed. I attribute all typos and errors to his help, and thank him for the opportunity to lay the blame at his paws. And lastly, my thanks and gratitude goes out to Mr. Bruce Frederick Springsteen, a man of heart and of conscience who constantly keeps me honest and aware that “it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive (Badlands).” -

The Holy Eucharist: Rite I

THE HOLY EUCHARIST: RITE I Th e Fourteenth Sunday aft er Pentecost August 29, 2021 | 11:00am Th e people’s responses are in bold. OPENING VOLUNTARY Grave and Adagio from Sonata No. 2 Felix Mendelssohn THE LITURGY OF THE WORD Please stand, as you are able, for the Opening Hymn. OPENING HYMN • 390 Praise to the Lord, the Almighty Lobe den Herren Blessed be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Th e Book of Common Prayer (BCP), p. 323 And blessed be his kingdom, now and for ever. Amen. Almighty God, unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen. THE SUMMARY OF THE LAW BCP, p. 324 Hear what our Lord Jesus Christ saith: Th ou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. Th is is the fi rst and great commandment. And the second is like unto it: Th ou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets. SONG# OF PRAISE Glory be to God (Hymnal S202) Willan # ˙ ˙ ˙ Œ ˙ ˙ Œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ #œ œ œ ˙ ˙ 1. Glo- ry be to God on high, and on earth peace, good will towards men. 2. We praise thee, we bless thee, ## Œ œ ˙ œ ˙ œ ˙ & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ w œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ we wor - ship thee, we glo- ri - fy thee, we give thanks to thee for thy great glo- ry, 3. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring.