Neuromuscular Thermography: an Analysis of Criticisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Glaucoma with Ocular Thermal Images Using GLCM Techniques

http://dx.doi.org/10.21611/qirt.2015.0098 Assessment of Glaucoma with Ocular Thermal Images using GLCM Techniques by N.Padmapriya1, N.Venkateswaran2, Toshitha Kannan3 and M. Sindhu Madhuri4 1,2,3,4 SSN College of Engineering, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, [email protected] http://www.ndt.net/?id=20259 Abstract This paper proposes a methodology for early detection and recognition of Glaucoma in ocular thermographs. Ocular thermography is an efficient tool not only to capture temperatures of corneal surface, but also to detect and visualize any changes on the Ocular surface temperature. The proposed method uses a linear transformation for pre- processing. Support vector machines (SVM) based classifier with the features collected from GLCM is used to classify the given ocular IR thermal image into Glaucoma from the normal eye. The efficacy of the proposed technique is proved over a number of ocular thermal image samples. Keywords: Thermography, Glaucoma, Ocular Surface Disorder, Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), More info about this article: Support vector machine (SVM). 1. Introduction Infrared (IR) thermography is a non-contact and non-intrusive temperature measuring technique, capable of displaying real-time surface temperature distribution. Thermography is an investigative technique which allows rapid color- coded display of the temperature across a wide surface by means of infrared detection. Infrared thermography is used in satellite imaging, movement detection, security, surveillance, etc. In medicine, thermography has been extensively used in the diagnosis of breast cancer, diabetes neuropathy and peripheral vascular disorders. In addition, it has been used to detect problems associated with gynaecology, kidney transplantation, dermatology, heart, neonatal physiology, fever screening and brain imaging [1]. -

Infrared Thermography — Revealing the Hidden Risks

Infrared Thermography — Revealing the Hidden Risks RISK CONTROL Infrared Thermography Saves Energy and Avoids Losses While electrical systems are among the most reliable equipment, We focus on prevention they do require periodic maintenance and inspection to Insurance companies have traditionally focused on controlling continue to supply power to buildings and facilities in a safe and the impact of property losses by using fire protection systems efficient manner. That’s why CNA has been offering infrared (IR) (such as sprinklers) to minimize losses when they happen. thermography tests to new and existing clients with total insured Rarely is a service offered that actually helps prevent losses to values (TIV) of $10 million or more per location. When it comes to save businesses real money. IR thermography is such a service. providing the advanced diagnostic services our clients need to A thermal imaging scan increases confidence in equipment, reduce risks ... we can show you more.® decreases the chance for fire loss, reduces energy costs and How IR thermography works helps avoid business interruption losses. Everything with a temperature above absolute zero releases Certified IR thermographers can conduct scans on equipment thermal, or infrared, energy. The light composed of this energy to find potential problems in the early stages of breakdown isn’t visible because its wavelength is too long to be detected or failure. Mechanical systems and key production equipment by the human eye. The higher an object’s temperature, the are also assessed during IR thermography. Infrared testing is a greater the IR radiation it emits. IR thermography cameras can point-in-time survey and should be completed during periods not only see this light, but can also delineate hot areas from cool of normal to maximum electrical loads. -

Thermography) for Population Screening and Diagnostic Testing of Breast Cancer

NZHTA TECH BRIEF SERIES July 2004 Volume 3 Number 3 Review of the effectiveness of infrared thermal imaging (thermography) for population screening and diagnostic testing of breast cancer Jane Kerr New Zealand Health Technology Assessment Department of Public Health and General Practice Christchurch School of Medicine Christchurch, NZ. Division of Health Sciences, University of Otago NEW ZEALAND HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT (NZHTA) Department of Public Health and General Practice Christchurch School of Medicine and Health Sciences Christchurch, New Zealand Review of the effectiveness of infrared thermal imaging (thermography) for population screening and diagnostic testing of breast cancer Jane Kerr NZHTA TECH BRIEF SERIES July 2004 Volume 3 Number 3 This report should be referenced as follows: Kerr, J. Review of the effectiveness of infrared thermal imaging (thermography) for population screening and diagnostic testing of breast cancer. NZHTA Tech Brief Series 2004; 3(3) Titles in this Series can be found on the NZHTA website: http://nzhta.chmeds.ac.nz/thermography_breastcancer.pdf 2004 New Zealand Health Technology Assessment (NZHTA) ISBN 1-877235-64-4 ISSN 1175-7884 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Tech Brief was commissioned by the National Screening Unit of the New Zealand Ministry of Health. The report was prepared by Dr Jane Kerr (Research Fellow) who selected and critically appraised the evidence. The research protocol for this report was developed by Ms Marita Broadstock (Research Fellow). The literature search strategy was developed and undertaken by Mrs Susan Bidwell (Information Specialist Manager). Mrs Ally Reid (Administrative Secretary) provided document formatting. Internal peer review was provided by Dr Robert Weir (Senior Research Fellow), Dr Ray Kirk (Director) and Ms Broadstock. -

THE TERMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS of the WELDING by TIG M.Sc., Eng

SCIENTIFIC PROCEEDINGS XI INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS "MACHINES, TECHNOLОGIES, MATERIALS" 2014 ISSN 1310-3946 THE TERMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE WELDING BY TIG M.Sc., Eng. Maś K., M.Sc. Woźny M., PhD. Marchewka M. , PhD. Płoch D. and Prof. Dr.Sheregii E.M. Centre for Microelectronics and Nanotechnology, University of Rzeszow, Poland [email protected] Abstract: Thermography measurements allow to detect the defects that may appear on a joint at welding of components. Energy pulse generated by a xenon lamp with adequate power in a short period of time is sufficient for thermal excitation and enables to register the temperature distribution using the thermography high resolution camera FLIR SC7000. The impulse with 6kJ energy and 6ms time generate sufficient power to measure the temperature distribution on the surface of the weld tested. During cooling the temperature of the area with defect changes more slowly than in the areas without defects, because of to the less intense heat dissipation. This allows the registration of defects in welds "on-line" at the production process. Material used for analysis detection of defects in the welded joints is Inconel 718, stainless steel 410 and stainless steel 321. The peak energy which flow throw the samples with defects in the welded joints its completely or partially blocked. It cause different temperature distribution on the surface in the places where the connection discontinuity take place. Keywords: THERMOGRAPHY, DEFECTS, WELDING, NDT 1. Introduction therefore, X-rays and gamma rays can be used to show discontinuities and inclusions within the opaque material. The Welded joints and padding layers are subjected to control permanent film record of the internal conditions will show the basic processes through the use of non-destructive testing methods to information by which the weld reliability and credibility could be ensure a high quality semi-finished and finished products [1-3]. -

About Thermography…

About Thermography… Page 1 About Beacon Thermography, Inc. Based in Surf City, NC Started March 2016 3 sisters Mostly mobile Home office Wilmington Elite Chiropractic Shaver Chiropractic McKay Healing Arts Raleigh-Durham Health Touch NC LLC Website www.beaconthermography.com Page 2 Shelly Laine Qualifications, Certifications and Accreditations Clinical Thermographer – MediTherm and The American College of Clinical Thermography Certified Health Coach – The Institute for Integrative Nutrition, New York City Board Certified and Accredited Member of the American Association of Drugless Practitioners (AADP) New Healers Master Coaching Program Certified BioEnergetic Synchronization Technique (B.E.S.T.) Practitioner – Morter Health Systems Active Isolated Stretching Practitioner – Aaron Mattes AIS and Strengthening, Basic and Advanced Trapped Emotion Release Aromatherapy – Raindrop Technique, Applied VitaFlex, Essential Oil Chemistry and Emotional Release with Essential Oils – Center for Aromatherapy Research and Education Continuing Education – Master Herbalist studies through School of Natural Healing BS Computer Science with 30 years of experience in Information Technology Leadership Page 3 Cecilia Laine-Meinhold Qualifications, Certifications and Accreditations Clinical Thermographer – MediTherm and member of The American College of Clinical Thermography Energy Work via Dowsing – mentored by internationally-known dowser Trapped Emotion Release Develops personalized organic skin care products Current studies: Master -

Thermography

Thermography Date of Origin: 04/2005 Last Review Date: 06/23/2021 Effective Date: 07/01/2021 Dates Reviewed: 03/2006, 03/2007, 03/2008, 03/2009, 02/2011, 03/2012, 01/2013, 12/2013, 06/2015, 06/2016, 06/2017, 06/2018, 06/2019, 06/2020, 06/2021 Developed By: Medical Necessity Criteria Committee I. Description Thermography, also known as thermal imaging, infrared imaging or temperature gradient studies, is a non-invasive imaging technique, which measures temperature variations at the body surface. The infrared radiation from the body tissue reveals temperature variations by producing brightly colored patterns on a liquid crystal display. Interpretation of the color patterns is thought to assist in the diagnosis of a variety of disorders and diseases. Thermography can include various types of telethermographic infrared detector images and heat-sensitive cholesteric liquid crystal systems. II. Criteria: CWQI HCS-0065 A. Moda Health considers thermography experimental and investigational for all indications. Available medical literature indicates thermography is an ineffective diagnostic technique with no proven medical value. III. Information Submitted with the Prior Authorization Request: 1. Not applicable. IV. CPT or HCPC codes NOT covered: Codes Description 93740 Temperature gradient studies V. Annual Review History Review Date Revisions Effective Date 01/2013 Annual Review: Added table with review date, revisions, and effective 01/23/2013 date. 12/2013 Annual Review: No changes 12/19/2013 06/2015 Added Medicare reference, ICD-9 codes 06/24/2015 Moda Health Medical Necessity Criteria Thermography Page 1/4 06/2016 Annual Review: Deleted ICD-9 codes, added ICD-10 codes, Annual 06/29/2016 Review 06/2017 Annual Review: Updated to new template; no changes 06/28/2017 06/2018 Annual Review: 07/01/2018 06/2019 Annual Review: Removed deleted codes; no changes 07/01/2019 06/2020 Annual Review: No content changes 07/01/2020 06/2021 Annual Review: No content change 07/01/2021 VII. -

Role of Thermography in the Diagnosis of Chronic Sinusitis

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.2298 Role of Thermography in the Diagnosis of Chronic Sinusitis Raja Kalaiarasi 1 , Chellappa Vijayakumar 2 , Ramalingam Archana 3 , Ramakrishnan Venkataramanan 4 , Ranganathan Chidambaram 5 , Sadhanandham Shrinuvasan 5 , Ravi Prabhu 6 1. Otorhinolaryngology, Sri Lakshmi Narayana Institute of Medical Science, Puducherry, India 2. Surgery, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India. 3. Preventive Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India. 4. Otolaryngology, Sri Lakshmi Narayana Institute of Medical Science, Puducherry, India 5. Radiology, Sri Lakshmi Narayana Institute of Medical Science, Puducherry, India 6. General Surgery, Sri Lakshmi Narayana Institute of Medical Science, Puducherry, India Corresponding author: Raja Kalaiarasi, [email protected] Abstract Introduction Thermography is a form of radiography that images the skin surface temperature. Thermograms are pictorial representations of thermal maps of the entire body’s outer surface. Thermography was applied as an attempt to evaluate its usefulness in the diagnosis of chronic sinusitis (CS). Hence, this study was done to determine the diagnostic value of thermography for patients suffering from CS. Methodology Patients attending the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery over a two years' duration with symptoms suggestive of CS were included in this diagnostic evaluation study. X-ray paranasal sinuses (PNS) and nose, thermography of head and neck, and computed tomography (CT) of PNS and nose (axial and coronal sections) were performed on them. The thermograms and X-ray sinuses obtained were compared with the computed tomography of PNS findings. Results The study population consisted of 167 patients (75 males and 92 females) and the mean age of the study population was 38.6 years. -

AAT Thermography Facts and Information

AAT Thermography Facts and Information What is Thermology? AAT has published internationally peer reviewed guidelines on Neuromusculoskeletal, Breast, Veterinary, and Oral Systemic Thermography. Medical Thermographic studies performed according to guidelines and under cold stress in humans are sympathetic skin response studies that involve the use of infrared imaging. Skin galvanic impedance, vasomotor and sudomotor physiology can be assessed through infrared skin response studies. Medical Thermology is completely non-contact and involves no form of energy imparted onto or into the body. Medical disciplines that may have interest in Medical Thermology include neurology and neurosurgery, physiatry, pain specialists, orthopedics, occupational medicine, vascular medicine, oncology, and dentistry. Sympathetic skin response studies such as cold stress infrared imaging provide valuable diagnostic tools for the study of complex regional pain syndromes (CRPS), reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), vasomotor headache and Barre-Lieou. Other established clinical indications include venous and peripheral arterial disorders such as insufficiency or vasospastic disease, rheumatic inflammation, trauma and post-operative or fracture pain. Breast Thermal imaging is not a diagnostic test for breast cancer but is a breast health risk assessment tool. It is an adjunct test to other breast imaging studies such as Mammography, MRI, or Ultrasound. Extensive literature exists on the use of infrared imaging as a breast risk health assessment. Estrogen dominance, ductal congestion, lymphatic congestion, and angiogenesis are all breast health risk factors that breast thermal imaging can help to identify. Oral Systemic Thermography can play an important adjunctive role in the assessment of Dental-Oral and certain Systemic Health related illnesses, diseases, and in their clinical diagnosis. -

The Herschel Heritage to Medical Thermography

Journal of Imaging Review The Herschel Heritage to Medical Thermography Francis Ring Medical Imaging Research Unit, Faculty of Mathematics Computing and Science, University of South Wales, Pontypridd CF37 1DL, UK; [email protected] Academic Editors: Carosena Meola and Gonzalo Pajares Martinsanz Received: 23 September 2015; Accepted: 25 March 2016; Published: 14 April 2016 Abstract: The discovery of infrared radiation by William Herschel in 1800 led to John Herschel’s study of solar radiation that he imaged by evaporography. This he termed a thermogram. The measurement of temperature in medicine advanced with Dr Carl Wunderlich, who showed the significance of the use of temperature measurements for diagnosis of fever and for monitoring the course of temperature in relation to disease. It was William and John Herschel’s discovery of infrared radiation that has ultimately opened up many applications for thermal imaging. Radiometric determination of human body (skin) temperature is now achievable. Remote sensing of infrared radiation first developed in the 1940s and has continued to develop steadily since 1960. Modern high speed and high resolution camera systems have now reached a dramatic level of performance at more modest costs, which medicine can now employ for non-invasive and quantifiable imaging. This has applications in many areas of medicine both for diagnostics and monitoring treatment. In recent years the acute threat of pandemic infection has increased, heightened by today’s ever expanding world travel. Special interest has been shown in the potential of thermal imaging for airport and travel screening. This is in effect where Dr Wunderlich’s studies began, and it has yet to be proven that the technique can be responsibly employed for efficient screening of large numbers of the travelling public. -

Thermographic Imaging in Cats and Dogs Usability As a Clinical Method

Recent Publications in this Series MARI VAINIONPÄÄ 1/2014 Hanna Rajala Molecular Pathogenesis of Large Granular Lymphocytic Leukemia DISSERTATIONES SCHOLAE DOCTORALIS AD SANITATEM INVESTIGANDAM UNIVERSITATIS HELSINKIENSIS 2/2014 Thermographic Imaging in Cats and Dogs Usability as a Clinical Method MARI VAINIONPÄÄ Thermographic Imaging in Cats and Dogs Usability as a Clinical Method DEPARTMENT OF EQUINE AND SMALL ANIMAL MEDICINE FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE AND DOCTORAL PROGRAMME IN CLINICAL VETERINARY MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI 2/2014 Helsinki 2014 ISSN 2342-3161 ISBN 978-952-10-9941-0 Department of Equine and Small Animal Medicine University of Helsinki Finland Thermographic imaging in cats and dogs Usability as a clinical method Mari Vainionpää, DVM ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in Walter Hall, University EE building, on June 6th 2014, at noon. Helsinki 2014 SUPERVISED BY: Outi Vainio, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ECVPT, Professor Marja Raekallio, DVM, PhD, University Lecturer Marjatta Snellman, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ECVDI, Professor Emerita Department of Equine and Small Animal Medicine Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland REVIEWED BY: Francis Ring, DSc, MSc, Professor Medical Imaging Research Unit Faculty of Advanced Technology University of South Wales Pontypridd, Wales, UK Ram Purohit DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACT, Professor Emeritus Department of Clinical Science College of Veterinary Medicine Auburn -

Thermography in Neurological and Musculoskeletal Conditions

AMA Council Report Thermography in Neurological and Musculoskeletal Conditions Thermography is a safe adjunctive physiological procedure which may be useful in the diagnosis of selected neurological and musculoskeletal condi- tions. Thermography is noninvasive and does not involve the use of ionizing radiation. Thermog- raphy may facilitate the determination of spinal nerve root and distal peripheral nerve dysfunction. Thermography also contributes to the evaluation of possible autonomic nervous system dysfunction and of spinal disorders. Thermography may be useful in documenting peripheral nerve and soft ‘tissue injuries, such as muscle and ligament sprain, inflammation, muscle spasm, and myositis. Thermography is helpful in the diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy and can be used to follow the course of patients after spinal surgery. In those applications, thermography does not stand alone as a primary diagnostic tool. It is a test of physiological function that may aid in the inter- pretation of the significance of information ob- tained by other tests. In recent years, an increasing number of correlative studies have been published. Few of these studies can be characterized as well- controlled. This fact limits attempts at a definitive analysis of the overall value of thermography. More research will help to clarify the exact contribution of thermography to diagnostic problems. INTRODUCTION Thermography is a diagnostic procedure that mea- sures infrared energy emitted by the skin. These measurements, expressed in the form of thermal images, constitute the basis for suggestions that ther- mography is useful in the diagnosis of painful condi- tions such as herniated disc disease, myofascial pain syndrome, myositis, musculoligamentous injury, From the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association, Chi- cago. -

Thermography Analysis Program to Meet These Requirements

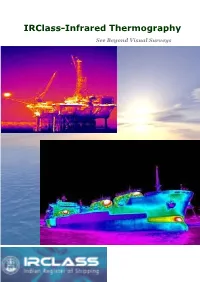

IRClass-Infrared Thermography See Beyond Visual Surveys Since the Ships Went into the Sea, Marine Applications of Thermography Surveyors have relied heavily on what they could Leak Detection (e.g. Boilers, Safety Valves see. Hear and felt to assess its sea worthiness Steam Pipes, Heaters, Coolers, Condensers, and condition. Now the infrared thermal camera Pumps, etc) enable the surveyor to instantly scan the Hull Structural Surveys structural integrity of the vessel, as well as Electrical Maintenance Electrical, on board electronics, Propulsion, Fluid Flow Problems Power generations, Boilers, fuel systems, Condition Based Maintenance Various Piping’s and find problems that are Research & development invisible and difficult to detect. Finding these Process Monitoring problems enables proactive maintenance plan Condition based Maintenance that will avoid catastrophic failures underway. Civil Structures, Moisture Detection What is Infrared Thermography? Furnaces & Boilers, refractory insulations Infrared thermograph is the science of Others acquisition and analysis of thermal information by using non contact thermal imaging devices. It is based on measuring the distribution of radiant thermal energy (heat) emitted from a target surface and converting this to a surface temperature map or thermogram. As a result, temperature can be a key parameter for monitoring and diagnosis the condition of machines, Process and installations. Boiler Tubes defects identification IRS has developed an infrared Thermography analysis Program to meet these requirements. It provides independent and thorough evaluation of the ships & Installations based on actual condition, in line with requirements towards the Pre Docking Strategy to identify & target Equipments, Pre Purchase Inspections to know the Overall condition, safety Audits of Ports and oil terminals, Offshore Installations.