PDF (V. 42:1, 2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclic Issue 32.Pdf

1 Cyclic Defrost Magazine Issue 32 | July 2013 www.cyclicdefrost.com Stockists Founder Contents The following stores stock Cyclic Defrost although Sebastian Chan 04 Editorial | Sebastian Chan arrival times for each issue may vary. Editors 06 Cover Designer | Jonathan Key NSW Alexandra Savvides 12 This Thing | Samuel Miers Black Wire, Emma Soup, FBi Radio, Goethe Shaun Prescott 16 The Longest Day | Chris Downton Institut, Mojo Music, Music NSW, Pigeon Ground, Sub-editor 20 Rise of the tape | Kate Carr The Record Store, Red Eye Records, Repressed Luke Telford 26 The Necks | Tony Mitchell Records, Title Music, Utopia Art Director 34 Arbol | Christopher Mann VIC Thommy Tran 40 Cyclic Selects | Bob Baker-Fish Collectors Corner Curtin House, Licorice Pie, Advertising latest reviews Polyester Records, Ritual Music and Books, Wooly Sebastian Chan Now all online at www.cyclicdefrost.com/blog Bully Advertising Rates QLD Download at cyclicdefrost.com Butter Beats, The Outpost, Rocking Horse, Taste-y Printing SA Unik Graphics B Sharp Records, Big Star Records, Clarity Records, Website Mr V Music, Title Music Adam Bell and Sebastian Chan WA Web Hosting 78 Records, Dadas, Fat Shan Records, Junction Blueskyhost Records, Mills Records, Planet Music, The Record www.blueskyhost.com Finder, RTRFM Cover Design TAS Jonathan Key Fullers Bookshop, Ruffcut Records Issue 32 Contributors NT Adrian Elmer, Alexandra Savvides, Bianca de Vilar, Bob Baker Fish, Chris Downton, Christopher Mann, Doug Happy Yess Wallen, Jonathan Key, Joshua Meggitt, Joshua Millar, ONLINE Kate Carr, Kristian Hatton, Luke Bozzetto, Samuel Miers, Twice Removed Records Stephen Fruitman, Tony Mitchell, Wayne Stronell, Wyatt If your store doesn't carry Cyclic Defrost, Lawton-Masi. -

Kennewick Pro Rodeo Champions

IN THIS ISSUE: • Pro Rodeos & World Standings, pg 3 • Glen Rose Summer Classic, Glen Rose, TX, pg 15 • Triangle Cross Classic, McCook, NE, pg 21 • Glen Wood Memorial, Salina, UT, pg 38 • Legends Of The South, Perry, GA, pg 48 AUGUST 31, 2021 // Volume 15: Issue 35 • Barrel Of Gold, Silesia, MT, pg 52 Published Weekly, online at www.BarrelRacingReport.com - Since 2007 KENNEWICK PRO RODEO CHAMPIONS SR Industry Titan & Destri Devenport — page 2 TRIANGLE CROSS GLEN WOOD CLASSIC Streakin On Fame MEMORIAL & Rose Hildebrandt Hello Stella — page 21 & Sharin Hall — page 38 Destri Devenport & SR Industry Titan Soar At Horse Heaven Kennewick Roundup By Tanya Randall Destri Devenport and SR Industry Titan, owned by Tom & Nick Wylie, have been on a hot streak in the Northwest. KENNEWICK PRO RODEO CHAMPIONS Together they’ve won three rodeos in the past two weeks, their SR Industry Titan & Destri Devenport biggest victory coming last week with a $8,965 victory at the $20,000-added Horse Heaven Kennewick Roundup in Washington. Flit Bar They also split second at the $10,000-added Kitsap Stampede in Fire Water Flit Bremerton, Washington, for total weekend earnings of $11,634. Slash J Harletta “I think he’s been run more in the last couple months than he has in his whole life, but he’s gotten stronger and stronger,” said Firewaterontherocks Devenport. The Escondido, California, barrel racer started running Ronas Ryon the 8-year-old stallion after the Fourth of July run. Rock N Roll Rona SI 105 SI 86 Their first run together was at Nephi, Utah, where the fresh Navas Bolder Girl from the breeding farm stallion playfully hopped his way through SI 104 the pattern. -

NRAO Enews Volume 12, Issue 5 • 13 June 2019

NRAO eNews Volume 12, Issue 5 • 13 June 2019 Upcoming Events NRAO Community Day at UMBC (https://science.nrao.edu/science/meetings/2019/umbc19/index) Jun 13 14, 2019 | Baltimore, MD CASCA 2019 (http://www.physics.mcgill.ca/casca2019/) Jun 17 20, 2019 | Montréal, Québec Radio/mm Astrophysical Frontiers in the Next Decade (http://go.nrao.edu/ngVLA19) Jun 25 27, 2019 | Charlottesville, VA 7th VLA Data Reduction Workshop (http://go.nrao.edu/vladrw) Oct 7 18, 2019 | Socorro, NM ALMA2019: Science Results and CrossFacility Synergies (http://www.eso.org/sci/meetings/2019/ALMA2019Cagliari.html) Oct 14 18, 2019 | Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy Semester 2019B Proposal Outcomes Lewis Ball The NRAO has completed the Semester 2019B proposal review and time allocation process (https://science.nrao.edu/observing/proposal-types/peta) for the Very Large Array (VLA) (https://science.nrao.edu/facilities/evla) and the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) (https://science.nrao.edu/facilities/vlba) . For the VLA a single configuration (the D array) will be available in the 19B semester and 124 new proposals were received by the 1 February 2019 submission deadline including one large and sixteen time critical (triggered) proposals. The oversubscription rate (by proposal number) was 2.5 and the proposal pressure (hours requested over hours available) was 2.1, both of which are similar to recent semesters. For the VLBA 27 new proposals were submitted, including two large proposals and one triggered proposal. The oversubscription rate was 2.1 and the proposal pressure was 2.3, both of which are similar to recent semesters. -

17-06-27 Full Stock List Drone

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST - JUNE 2017 (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €17) Amish Glamour (do-CD, 2012, Nitkie Records Patch ten, €17) 1000SCHOEN / AB INTRA Untitled (do-CD, 2014, Zoharum ZOHAR 070-2, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10inch, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2:13 PM Anus Dei (CD, 2012, 213Records 213cd07, €10) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) Speak to me (LP, 2016, Black Truffle BT023, €17.5) 300 BASSES Sei Ritornelli (CD, 2012, Potlatch P212, €15) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth (CD, 1994, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu1, €14) 7JK (SIEBEN & JOB KARMA) Anthems Flesh (CD, 2012, Redroom Records REDROOM 010 CD , €13) 87 CENTRAL Formation (CD, 2003, Staalplaat STCD 187, €8) @C 0° - 100° (CD, 2010, Monochrome -

2016 RESEARCH and CREATIVE WORKS SYMPOSIUM from EVERY VOICE Southwestern University Georgetown, Texas

1 2 2016 RESEARCH AND CREATIVE WORKS SYMPOSIUM FROM EVERY VOICE Southwestern University Georgetown, Texas EVENT PLANNER Christine C. Vasquez Office of the Dean of Faculty Southwestern University STUDENT PROGRAM CHAIR Emma McDaniel ‘16 English and Religion Departments Southwestern University FACULTY SPONSOR Dr. Alison Kafer Professor of Feminist Studies Southwestern University 3 4 Table of Contents SCHEDULE AT A GLANCE ................................................................................... 6 MAP OF ACTIVITIES .......................................................................................... 7 PANEL ABSTRACTS ............................................................................................ 8 CREATIVE WORKS AND EXHIBITION ABSTRACTS ............................................. 15 ORAL PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS ................................................................... 26 POSTER PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS ............................................................... 48 INDEX ............................................................................................................. 73 5 SCHEDULE AT A GLANCE MONDAY, APRIL 11 , 2016 3:00-8:00 Registration Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center TUESDAY, APRIL 12, 2016 8:00-3:00 Information and Volunteer Check-in Table Bishops Lounge 9:30-9:45 Introduction and Welcoming Remarks Main Lawn Dr. Alison Kafer, Professor of Feminist Studies Dr. Edward Burger, President of Southwestern University 9:45-10:00 Southwestern Andean Ensemble Main Lawn Amara Yachimski ‘17, Mattie -

Insight to Mars 07> Beagle 2 Found

SpaceFlight A British Interplanetary Society publication Volume 60 No.7 July 2018 £5.00 Deep impact: InSIGHT to Mars 07> Beagle 2 found 634072 Space age prophet 770038 9 Soyuz landing sites CONTENTS Features 14 Along paths trod by Vikings NASA’s InSIGHT Mars mission is off and running but how does it fit within the general pattern of Mars exploration and what can we expect of it, with its twin CubeSats designed to relay communications during the crucial descent? 14 18 Lost & Found Letter from the Editor Dr Jim Clemmet explains how Beagle 2 came to Just as we were going to press, be found residing apparently intact on the news broke of the death of Alan surface of Mars and how images from Mars Bean, Lunar Module Pilot for Reconnaissance Orbiter have helped rewrite the NASA’s second Moon landing and final chapter of this so very nearly successful Commander of the second mission. expedition to Skylab. An exceptional astronaut, we will 26 Prophet of the Space Age carry a formal obituary of Alan Author of a seminal biography of the renowned next month. In the meantime, for a 18 very personal insight into this space age publicist Willy Ley, Jared S Buss gets remarkable man, please see the behind this sometimes enigmatic character and letter from Nick Spall on page 42. helps us understand how he planted the first Elsewhere in this issue, we look seeds of expectation before Wernher von Braun into the mission of NASA’s next picked up the baton. Mars lander, now on its way to the planet, and hear from the chief 30 Happy landings engineer for the Beagle 2 Phillip S. -

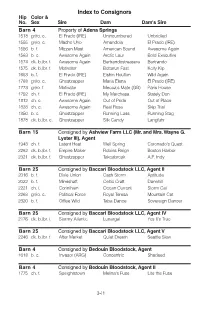

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Sire Dam Dam's Sire Barn 4 Property of Adena Springs 1518 gr/ro. c. El Prado (IRE) Unincumbered Unbridled 1555 gr/ro. c. Macho Uno Amandola El Prado (IRE) 1556 b. f. Mizzen Mast American Sound Awesome Again 1563 b. c. Awesome Again Arctic Laur Bold Executive 1574 dk. b./br. f. Awesome Again Bertrandostreasure Bertrando 1575 dk. b./br. f. Motivator Bettarun Fast Kelly Kip 1653 b. f. El Prado (IRE) Eishin Houlton Wild Again 1768 gr/ro. c. Ghostzapper Maria Elena El Prado (IRE) 1773 gr/ro. f. Motivator Mecca's Mate (GB) Paris House 1792 ch. f. El Prado (IRE) My Marchesa Stately Don 1812 ch. c. Awesome Again Out of Pride Out of Place 1838 ch. c. Awesome Again Real Rose Skip Trial 1850 b. c. Ghostzapper Running Lass Running Stag 1878 dk. b./br. c. Ghostzapper Silk Candy Langfuhr Barn 15 Consigned by Ashview Farm LLC (Mr. and Mrs. Wayne G. Lyster III), Agent 1948 ch. f. Latent Heat Well Spring Coronado's Quest 2262 dk. b./br. f. Empire Maker Robins Reign Boston Harbor 2321 dk. b./br. f. Ghostzapper Takeabreak A.P. Indy Barn 25 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent II 2016 b. f. Dixie Union Cash Storm Aptitude 2022 b. f. Mineshaft Celtic Craft Danehill 2221 ch. f. Corinthian Ocean Current Storm Cat 2268 gr/ro. c. Political Force Royal Teresa Mountain Cat 2320 b. f. Offlee Wild Taba Dance Sovereign Dancer Barn 25 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent IV 2176 dk. -

Wallace L. W. Sargent 1935–2012

Wallace L. W. Sargent 1935–2012 A Biographical Memoir by Charles C. Steidel ©2021 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. WALLACE L. W. SARGENT February 15, 1935-October 29, 2012 Elected to the NAS, 2005 Wallace L. W. Sargent was the Ira S. Bowen Professor of Astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, where he was a member of the astronomy faculty for 46 years, beginning in 1966. By any measure, Sargent— known to colleagues and friends as “Wal”—was one of the most influential and consistently productive observa- tional astronomers of the last 50 years. His impact on the field of astrophysics spanned a remarkably wide range of topics and was seminal in more than a few: the primor- dial helium abundance, young galaxies, galaxy dynamics, supermassive black holes, active galactic nuclei (AGN), Technology. Institute of Photography by California and, particularly, the intergalactic medium (IGM). Wal was 77 at the time of his death in 2012; he had maintained a full complement of teaching and research until just weeks By Charles C. Steidel before succumbing to an illness he had borne quietly for more than 15 years. Generations of students, postdocs, and colleagues benefited from Wal’s rare combination of scientific taste and intuition, intellectual interests extending far beyond science, irreverent sense of humor, and genuine concern about the well-being of younger scientists. Education and Early Influences Wal was born in 1935 in Elsham, Lincolnshire, United Kingdom—a small village roughly equidistant from Sheffield and Leeds in West Lincolnshire—into a working-class family. -

March/June 2015

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NORTH DAKOTA LIBRARY ASSOCIATION March-June 2015 NDLA Website - http://www.ndla.info Volume 45 • Issue 1-2 SnapshotSnapshot DayDay Photos Capture NDLA Libraries AND NationalNational LibraryLibrary WeekWeek 20152015 Celebrations t NDLA Legislative Day t Grad School Experience t Five Ways to Fully Engage t NDLA Conference Update INSIDE t Did you know …? Historical Nugget Table of Contents President’s Message ................................................. 3 Comstock Reading Aloud Initiative ....................... 4 Digital Public Library of America: Get Involved! ......................................................... 5 Did You Know...? NDLA Historical Nugget ........... 5 Five Ways to Fully Engage in NDLA ....................... 6 Flicker Tale Children’s Book Award ....................... 7 NDLA Membership Dues and Conference Fees ................................................. 8 2015 NDLA Spring Workshop .............................. 8 Published quarterly by the North Dakota Library Association MPLA Seeks Award Nominations ........................ 9 NDLA Legislative Day at the Capitol ................... 10 Editorial Committee Marlene Anderson, Chair Grants Available through Joan Erickson Eric Stroshane Mountain Plains Library Association ................ 12 Production Artist Canoe Kudos Awards ............................................ 13 Clearwater Communications, Robin Pursley Browsing in the Cyberstacks ................................ 14 Subscription Rate Grad School Experience: $25/year Go -

Astronomy and Astrophysics in the New Millennium an Overview

Astronomy and Astrophysics in the New Millennium an overview Astronomy and Astrophysics Survey Committee Board on Physics and Astronomy Space Studies Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences National Research Council National Academy Press Washington, D.C. ABOUT THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES For more than 100 years, the National Academies have provided independent advice on issues of science, technology, and medicine that underlie many questions of national importance. The National Academies—comprising the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council—work together to enlist the nation’s top scientists, engineers, health professionals, and other experts to study specic issues. The results of their deliberations have inspired some of America’s most signicant and lasting efforts to improve the health, education, and welfare of the nation. To learn more about Academies’ activities, check the Web site at www.nationalacademies.org. The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee whose work this report summarizes were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This project was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Grant No. NAG5-6916, the National Science Foundation under Grant No. AST-9800149, and the Keck Foundation. Additional copies of this report are available from: Board on Physics and Astronomy, National Research Council, HA 562, 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20418; Internet <http://www.nationalacademies.org/bpa>. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barns 9 & 10 Property of Adena Springs Broodmares 2849 ch. m. Optimistic Bullet (BRZ), 2007 Dancer Man Optativa 2850 ch. m. Orange Twist, 2009 Awesome Again Unbridled Ambiance 2860 b. m. Princess Daisy, 2008 Touch Gold Altar Girl 2875 b. m. Ritzy Girl, 2010 Ghostzapper Starship Cruiser 2884 ch. m. Sacredness, 2006 Holy Bull Popozinha 2887 b. m. Saradun, 1998 Hunting Hard Dundrum Dancer 2889 b. m. Saucy Girl, 2009 Wilko Affluent Appeal 2900 b. m. Silent Run, 2009 Silent Name (JPN) Royal Flotilla 2906 b. m. Skylara, 2008 Ghostzapper Champagne Cocktail 2913 gr/ro. m. Somebody Nice, 2009 Alphabet Soup Santana Anna 2934 b. m. Sugar Bird, 2009 Vindication Estimation (GB) 2935 dk. b./br. m. Sugar Dame, 2009 Ghostzapper Rich N Clever 2962 dk. b./br. m. Validain, 2005 Kafwain Valid Annie 2964 dk. b./br. m. Vitellia, 2009 Awesome Again Search the Church 2966 b. m. Water Lili, 2010 Awesome Again Here's to You 2970 dk. b./br. m. What a Lily, 2009 Vindication Ain't She Awesome 2973 b. m. Wilko Rose, 2010 Wilko Lil E Rose 2974 b. m. Willowy Wendy, 2009 Wilko Gijima 2981 b. m. Adios Caballero, 2009 El Prado (IRE) Langano 3030 b. m. Broadway Number, 2009 Holy Bull Jazznwithwindy 3045 ch. m. Catena Zapata (BRZ), 2007 Thignon Lafre (BRZ) Daisy Clover 3047 b. m. Celidonia, 2008 North Light (IRE) Quatrain 3048 b. m. Celtic Dance, 2010 North Light (IRE) Daytime Promise 3063 b. m. Consilia, 2009 Vindication Golden Corona 3064 b. -

International Evaluation of Onsala Space Observatory

INTERNATIONAL EVALUATION OF ONSALA SPACE OBSERVATORY VETENSKAPSRÅDETS RAPPORTSERIE 7:2010 INTERNATIONAL EVALUATION OF ONSALA SPACE OBSERVATORY August 31–September 3, 2009 INTERNATIONAL EVALUATION OF ONSALA SPACE OBSERVATORY August 31–September 3, 2009 This report can be ordered at www.vr.se VETENSKAPSRÅDET Swedish Research Council Box 1035 101 38 Stockholm, SWEDEN © Swedish Research Council ISSN 1651-7350 ISBN 978-91-7307-173-4 Graphic Design: Erik Hagbard Couchér, Swedish Research Council Cover Photo: Jan-Olof Yxell Printed by: CM-Gruppen AB, Bromma, Sweden 2010 To the Swedish Research Council Stockholm Sweden Ref: International Evaluation of Onsala Space Observatory Hereby we submit the evaluation report for Onsala Space Observatory (OSO). The report is based on the background evaluation report (827-2009- 439) and a site visit to OSO on September 1st, 2009. Särö, September 3rd, 2009 Véronique Dehant C. Malcolm Walmsley Anneila Sargent Expert Panel Expert Panel Expert Panel Karl-Fredrik Berggren David Edvardsson Chair Secretary, Swedish Research Council TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE. 7 II. SAMMANFATTNING. 8 III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 10 1. BACKGROUND. 12 2. THE SWEDISH RESEARCH COUNCIL AND THE NATIONAL FACILITIES. 14 3. SHORT DESCRIPTION OF ONSALA SPACE OBSERVATORY. 15 4. PANEL’S REPORT. 18 4.1 Organization. 19 4.2 Science 2006–2009. 19 4.3 Technical 2006–2009. 20 4.4 Community support 2006–2009. 21 4.5 Education and outreach. 21 4.6 The future of Onsala Space Observatory. 22 APPENDIX 1. BACKGROUND OF EXPERTS. 24 APPENDIX 2. TERMS-OF-REFERENCE. 29 APPENDIX 3. TIMEPLAN. 31 APPENDIX 4. QUESTIONNAIRE TO ONSALA SPACE OBSERVATORY . 33 APPENDIX 5.