Issue 31 2 January/February 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Deborah P Kolodji

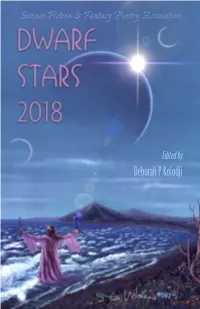

Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association Edited by Deborah P Kolodji The Dwarf Stars anthology is a selection of the best speculative poems of ten lines or fewer (100 words or fewer for prose poems) from the previous year, nominated by the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association membership and chosen for publication by the editors. From this anthology, SFPA members vote for the best poem. The winner receives the Dwarf Stars Award, which is analogous to the SFPA Rhysling Awards given annually for poems of any length. 1 Cover: Ritual by Steven Vincent Johnson acrylic on board © 1978 sjvart.orionworks.com The text was set in Agenda, ITC Busorama BT, Caflisch Script, and Cantoria MT. using Adobe InDesign. * © 2018 Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association sfpoetry.com All rights to poems retained by individual poets. Dwarf Stars 2018 The Best Very Short Speculative Poems Published in 2017 edited by Deborah P Kolodji Introduction THE SHORT OF IT As the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association celebrates its 40th Anniversary, I feel honored to return to my original (2006) role as the Dwarf Stars editor. An unofficial “demonstration” Dwarf Stars chapbook in 2005 was used to try to convince the membership to create a short-short Rhysling Award category. My position then and now is that a very short poem is read differently than a longer poem, and it is difficult to compare a haiku to a 49-line narrative poem. A haiku’s beauty lies in what is not being said; the reader sits with the poem and allows it to resonate. A longer narrative poem is experienced more like a story, the poem leading the reader on an adventure through its detailed imagery. -

Magazine of Canadian Speculative Poetry (Issue #2 – June, 2021)

POLAR STARLIGHT Magazine of Canadian Speculative Poetry (Issue #2 – June, 2021) POLAR STARLIGHT Magazine Issue #2 – June, 2021 (Vol.1#2.WN#2) Publisher: R. Graeme Cameron Editor: Rhea E. Rose Proofreader: Steve Fahnestalk POLAR STARLIGHT is a Canadian semi-pro non-profit Science Fiction Poetry online PDF Magazine published by R. Graeme Cameron at least three times a year. Distribution of this PDF Magazine is free, either by E-mail or via download. POLAR STARLIGHT buys First Publication (or Reprint) English Language World Serial Online (PDF) Internet Rights from Canadian Science Fiction Genre Poets and Artists. Copyright belongs to the contributors bylined, and no portion of this magazine may be reproduced without consent from the individual Poet or Artist. POLAR STARLIGHT offers the following Payment Rates: Poem – $10.00 Cover Illustration – $40.00 To request to be added to the subscription list, ask questions, or send letters of comment, contact Editor Rhea E. Rose or Publisher R. Graeme Cameron at: < Polar Starlight > All contributors are paid before publication. Anyone interested in submitting a poem or art work, and wants to check out rates and submission guidelines, or anyone interested in downloading current and/or back issues, please go to: < http://polarborealis.ca/ > Note: The Polar Borealis Magazine website is also the web site for Polar Starlight Magazine. ISSN 2369-9078 (Online) Headings: Engravers MT By-lines: Monotype Corsiva Text: Bookman Old Style 1 Table of contents 03) – EDITORIAL – Rhea E. Rose 04) – GOD OF THE APOCALYPSE – by Neile Graham 05) – CHILDREN OF THE DREAMWAYS – by Marcie Lynn Tentchoff 07) – WATCHMAKER – by Carolyn Clink 08) – UNBOUND – by James Grotkowski 09) – AN OTHER REVOLUTION – by Changming Yuan 10) – SHE FOLLOWS – by Robert Stevenson 11) – CHRYSALIS – by Roxanne Barbour 12) – ÉDOUARD MANET STAYS FOR DINNER – by Carla Stein 13) – THEY NEVER LET ME SLEEP – by Josh Connors 14) – THE SPIRE – by A.O. -

Auroran Lights

AURORAN LIGHTS The Official E-zine of the Canadian Science Fiction & Fantasy Association Dedicated to Promoting the Prix Aurora Awards and the Canadian SF&F Genre (Issue # 14 –December/January 2014/2015) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 – EDITORIAL CSFFA SECTION 04 – 2015 Aurora Award Eligibility List open. 04 – 2015 Aurora Award Nominations open. 04 – CSFFA AGM. 04 – 2015 Aurora Award Voting start date. PRODOM SECTION 05 – MILESTONES – Matthew Hughes & Jack Vance 05 – AWARDS – Sunburst Awards, Rhysling Poetry Awards. 09 – CONTESTS – Friends of the Merril Short Story Contest, Roswell Short Story Contest, Subterrain Magazine Fiction, Poetry & Non-Fiction Contest, Pulp Literature Magazine Swallows Sequential Graphic Arts Short Story Contest. 15 – EVENTS – ChiZine readings – Christi Charish & Jennifer Lott 10 – POETS & POEMS – Brains, Brains, Brains by Puneet Dutt, A Portrait of the Monster as an Artist by Dominik Parisien, 16 – PRO DOINGS – Condolences to Spider Robinson and how you can help him. 16 – CURRENT BOOKS – To Make a Witch by Heather Hamilton-Senter, Titanium Black by Michael J. Lee, An Inconvenient Corpse by Jason E. Rolfe, The Scrambled Man by Michael J. Bertrand, 17 – UPCOMING BOOKS & STORIES – The Occasional Diamond Thief by J.A. McLachlan, When Things Go Wobbly by Gregg Chamberlain, Ten Little Zombies by Gregg Chamberlain, Mirrors Heart by Justine Alley Dowsett and Murandy Damodred, 20 – MAGAZINES – Apex Magazine, Uncanny Magazine, Canadian Science Fiction Review, Sci Phi Journal, Galaxy’s Edge Magazine. 27 – MARKETS – Ideomancer Magazine, Uncanny Magazine, Canadian Science Fiction Review, Bundoran Press, SCIFI Journal, Clockwork Anthology, Mythic Derlium Magazine, Tartarus Press, Terraform Online Magazine, Third Person Press, Mirror World Publishing. -

W41 PPB-Web.Pdf

The thrilling adventures of... 41 Pocket Program Book May 26-29, 2017 Concourse Hotel Madison Wisconsin #WC41 facebook.com/wisconwiscon.net @wisconsf3 Name/Room No: If you find a named pocket program book, please return it to the registration desk! New! Schedule & Hours Pamphlet—a smaller, condensed version of this Pocket Program Book. Large Print copies of this book are available at the Registration Desk. TheWisSched app is available on Android and iOS. What works for you? What doesn't? Take the post-con survey at wiscon.net/survey to let us know! Contents EVENTS Welcome to WisCon 41! ...........................................1 Art Show/Tiptree Auction Display .........................4 Tiptree Auction ..........................................................6 Dessert Salon ..............................................................7 SPACES Is This Your First WisCon?.......................................8 Workshop Sessions ....................................................8 Childcare .................................................................. 10 Children's and Teens' Programming ..................... 11 Children's Schedule ................................................ 11 Teens' Schedule ....................................................... 12 INFO Con Suite ................................................................. 12 Dealers’ Room .......................................................... 14 Gaming ..................................................................... 15 Quiet Rooms .......................................................... -

Balticon 47 Program Participants

BALTICON 47 52 THE BSFAN Balticon 47 Program Participants JoAnn W. Abbott A. L. Davroe Heidi Hooper Danielle Ackley-McPhail Susan de Guardiola Starla Huchton Lisa Adler-Golden Donna Dearborn Kara Hurvitz D. H. Aire (Barry Nove) James K. Decker Michele Hymowitz Leigh Alexander Ming Diaz Eric Hymowitz Tristan Alexander Tim Dodge Christopher Impink Day Al-Mohamed Tom Doyle Noam Izenberg Scott H. Andrews Valerie Durham Mark Jeffrey Ami Angelwings James Durham Leslie Johnston Catherine A. Asaro Collin Earl Paula S. Jordan John Ashmead Gaia Eirich Jason Kalirai Lisa Ashton Chris Evans Amy L. Kaplan Thomas G. Atkinson Eric “Dr. Gandalf ” Fleischer Bruce Kaplan Jason Banks Halla Fleischer Debra Kaplan Brick Barrientos Judi Fleming William H. Kennedy Martin Berman-Gorvine Doc Frankenfield Kira Deja Biernesser D. Douglas Fratz James R. Knapp Steve Biernesser Nancy C. Frey Jonah Knight Joshua Bilmes Clint Gaige Beatrice Kondo Danny Birt Allison Gamblin Yoji Kondo (Eric Kotani) Roxanne Bland Charles E. Gannon Brian Koscienski Art Blumberg Lia Garrott A B Kovacs Sue Bowen Dr. Pamela L. Gay Laura E. Kovalcin Walter H. Boyes, Jr. Marty Gear Theodore Krulik William T. (Tom) Bridgman Veronica (V.) Giguere Alessandro La Porta Alessia Brio Phil Giunta Mur Lafferty J. Sherlock III Brown Alicia Goranson Jagi Lamplighter KT Bryski James L. Gossard Grig “Punkie” Larson Stephanie Burke Stephen Granade Marcus Lawrence Laura Burns Matthew Granoff Dina Leacock Mildred G. Cady Bob Greenberger R. Allen Leider Jack Campbell Irina Greenman Neal Levin Renee Chambliss Damien Walters Grintalis Emily Lewis Christine Chase Sonya “Patches” Gross Carey Lisse Robert R. Chase Gay Haldeman ScienceTim Livengood Bryan Chevalier Joe Haldeman Andy Love Ariel Cinii Elektra Hammond Steve Lubs Carl Cipra Eric V. -

Fantasy Magazine, Issue 60 (People of Colo(U)R Destroy Fantasy

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 60, December 2016 People of Colo(u)r Destroy Fantasy! Special Issue FROM THE EDITORS Preface Wendy N. Wagner People of Colo(u)r Editorial Roundtable POC Destroy Fantasy! Editors ORIGINAL SHORT FICTION edited by Daniel José Older Black, Their Regalia Darcie Little Badger (illustrated by Emily Osborne) The Rock in the Water Thoraiya Dyer The Things My Mother Left Me P. Djèlí Clark (illustrated by Reimena Yee) Red Dirt Witch N.K. Jemisin REPRINT SHORT FICTION selected by Amal El-Mohtar Eyes of Carven Emerald Shweta Narayan gezhizhwazh Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (illustrated by Ana Bracic) Walkdog Sofia Samatar Name Calling Celeste Rita Baker NONFICTION edited by Tobias S. Buckell Learning to Dream in Color Justina Ireland Give Us Back Our Fucking Gods Ibi Zoboi Saving Fantasy Karen Lord We Are More Than Our Skin John Chu Crying Wolf Chinelo Onwualu You Forgot to Invite the Soucouyant Brandon O’Brien Still We Write Erin Roberts Artists’ Gallery Reimena Yee, Emily Osborne, Ana Bracic AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS edited by Arley Sorg Darcie Little Badger Thoraiya Dyer P. Djèlí Clark N.K. Jemisin Shweta Narayan Leanne Betasamosake Simpson Sofia Samatar Celeste Rita Baker MISCELLANY Subscriptions & Ebooks Special Issue Staff © 2016 Fantasy Magazine Cover by Emily Osborne Ebook Design by John Joseph Adams www.fantasy-magazine.com FROM THE EDITORS Preface Wendy N. Wagner | 187 words Welcome to issue sixty of Fantasy Magazine! As some of you may know, Fantasy Magazine ran from 2005 until December 2011, at which point it merged with her sister magazine, Lightspeed. Once a science fiction-only market, since the merger, Lightspeed has been bringing the world four science fiction stories and four fantasy shorts every month. -

Philosophers' Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction

Philosophers’ Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction Recommendations, Organized by Author / Director November 3, 2014 Eric Schwitzgebel In September and October, 2014, I gathered recommendations of “philosophically interesting” science fiction – or “speculative fiction” (SF), more broadly construed – from thirty-four professional philosophers and from two prominent SF authors with graduate training in philosophy. Each contributor recommended ten works of speculative fiction and wrote a brief “pitch” gesturing toward the interest of the work. Below is the list of recommendations, arranged to highlight the authors and film directors or TV shows who were most often recommended by the list contributors. I have divided the list into (A.) novels, short stories, and other printed media, vs (B.) movies, TV shows, and other non- printed media. Within each category, works are listed by author or director/show, in order of how many different contributors recommended that author or director, and then by chronological order of works for authors and directors/shows with multiple listed works. For works recommended more than once, I have included each contributor’s pitch on a separate line. The most recommended authors were: Recommended by 11 contributors: Ursula K. Le Guin Recommended by 8: Philip K. Dick Recommended by 7: Ted Chiang Greg Egan Recommended by 5: Isaac Asimov Robert A. Heinlein China Miéville Charles Stross Recommended by 4: Jorge Luis Borges Ray Bradbury P. D. James Neal Stephenson Recommended by 3: Edwin Abbott Douglas Adams Margaret -

Kelly Jennings

Kelly Jennings Department of English 2813 Oakview Road University of Arkansas – Fort Smith Fort Smith, AR 72908 5210 Grand Avenue, P.O. Box 3649 [email protected] Fort Smith, AR, 72913 [email protected] 704-788-7907 479-763-5795 Education Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, University of Arkansas, 1995 Specialization in Greek, Roman, and World Literature Dissertation: Translation as Metaphor: The Function of Change in Roman Constructions of Greek Poetry. Dissertation directed by Dr. David Fredrick Coursework included several classes in Asian literature Degree required demonstrated competency in Greek and Latin M.F.A. in Fiction Writing, University of Arkansas, 1990 Thesis: Love Me Like a Rock. Thesis advisor was Professor James Whitehead Coursework included classes in the form and theory of Fiction, Poetry, and Translation B.A. in English, University of New Orleans, 1983 Publications: Fiction: Books & Anthologies Triple Junction. Under consideration Broken Slate. Crossed Genre Press, Somerville, MA: July 2011. Print. Menial: Skilled Labor in Science Fiction. Eds. Kelly Jennings and Shay Darrach. Crossed Genre Press. Somerville, MA: January 2013. Print. Crossed Genres 2.0: Book Three. Eds. Bart Leib, Kay T. Holt, and Kelly Jennings. Somerville, MA: 2014. Print. Crossed Genres: Year Two. Eds. Kay T. Holt, Kelly Jennings, and Bart Leib. Somerville, MA: 2010. Print. Crossed Genres Magazine. Eds. Eds. Kay T. Holt, Kelly Jennings, and Bart Leib. Issues 25 through current. January 2015 onward. Web. Crossed Genres Magazine. Eds. Kay T. Holt, Kelly Jennings, and Bart Leib. Issues 19 through 24. July through December 2014. Web. Crossed Genres Magazine. Eds. Kay T. Holt, Kelly Jennings, and Bart Leib. -

One Hundred and Eighty Literary Journals for Creative Writers

180 Literary Journals for Creative Writers Emily Harstone Authors Publish COPYRIGHT 2018 AUTHORS PUBLISH DO NOT DISTRIBUTE WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION QUESTIONS, COMPLAINTS, COMMENTS, CORRECTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] COPY EDITING: S. KALEKAR COVER DESIGN BY JACOB JANS COVER IMAGE CREDIT: SKITTERPHOTO Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 5 HOW TO START GETTING YOUR WORK PUBLISHED IN LITERARY JOURNALS .............................................................................................. 7 AGAINST SUBMISSION FEES ................................................................ 11 10 GREAT NEW LITERARY JOURNALS ................................................... 13 25 LITERARY JOURNALS ALWAYS OPEN TO SUBMISSIONS .................. 16 15 JOURNALS WITH FAST RESPONSE TIMES....................................... 20 17 APPROACHABLE LITERARY JOURNALS ........................................... 23 26 RESPECTED LITERARY JOURNALS AND MAGAZINES THAT PUBLISH CREATIVE WRITING ............................................................................... 26 13 LITERARY JOURNALS OPEN TO OTHER ART FORMS ....................... 31 25 LITERARY JOURNALS THAT PAY THEIR WRITERS............................34 40 LITERARY JOURNALS THAT PUBLISH GENRE WRITING ................... 38 9 LITERARY JOURNALS THAT PUBLISH LONGER FICTION .................... 44 PLACES TO FIND MORE LITERARY JOURNALS ...................................... 46 GLOSSARY OF TERMS ......................................................................... -

Speculative Poetry Reading and Writing Workshop

Rochester Speculative Literature Association, Inc. Speculative Poetry Reading and Writing Workshop by Alan Vincent Michaels What is Speculative Poetry? Speculative fiction poetry is a subgenre of poetry primarily focused on fantastical, science fictional, and mythological themes. Although speculative poetry is defined by its subject matter, the form selected can play a significant role in shaping the meaning, tone, and quality of the poem. Suzette Haden Elgin, founder of the Science Fiction Poetry Association, defined the subgenre as “about a reality that is in some way different from the existing reality.” Elizabeth Barrette opens her 2008 essay, Appreciating Speculative Poetry, with: When most people hear “science fiction,” they think of fiction and not poetry. Fantasy and horror have a less exclusive phrasing, but still, genre readers are more inclined to forget about poetry. It remains, however, a vital part of speculative literature. A genre is defined more by focus than by form. The speculative field—in all its myriad subdivisions—bases itself on the prime question, “What if?” Speculative poetry is simply exploration of “What if?” in verse. (source: The Internet Review of Science Fiction http://www.irosf.com/q/zine/article/10426) Comparing Poetry and Prose Poetry and prose are two sides of the same speculative literary coin. They are the methods by which speculative ideas are conveyed from the writer's mind to her readers. Although poetry and fiction are related through their subject matter, their forms are indeed different. As Elizabeth Barrette describes in Appreciating Speculative Poetry: • Poetry is more concise than fiction • Poetry is more memorable than prose • Poetry is bound by different rules than fiction • Poetry is intended to call attention to language • Poetry is more suited to describing the indescribable (source: The Internet Review of Science Fiction http://www.irosf.com/q/zine/article/10426) Speculative fiction poetry, contrary to what you may think, is not just genre fiction told in verse. -

Download The

HELIOTROPE www.heliotropemag.com The Speculative Fiction Magazine They Play in the Palace of my Dreaming • by Gerard Houarner A Godmother’s Gift • by January Mortimer Galatea • by Vylar Kaftan Volume 1 Issue 2 April, 2007 Volume With a Poem From Sonya Taaffe Short Fiction They Play in the Palace of My Dreaming by Gerard Houarner 6 Galatea by Vylar Kaftan 20 A Godmother’s Gift by January Mortimer 31 Poetry Fasti by Sonya Taaffe 42 Contents • Heliotrope • April 007 Author Bios January Mortimer lives in London with her goldfish and a frightening number of house plants. She is an ecologist, so where ever she is right now, it is probably muddy. Her stories have appeared in Ideomancer, Fantasy Magazine and the anthology Ecotastrophe. For more on her and her work, visit her journal at www.januaryhat.livejournal.com Gerard Houarner is a product of the NYC school system who lives in the Bronx, was married at a New Orleans Voodoo Temple, and works at a psychiatric institution. He’s had hundreds of short stories, a few novels and story collections, as well as a couple of anthologies published, all dark. To find out about the latest, visit www.cith.org/gerard, www. myspace.com/gerardhouarner or his board at www.horrorworld.org Vylar Kaftan writes science fiction, fantasy, horror, slipstream, and cleverly-phrased Post-It notes on the fridge. Her stories have appeared in Strange Horizons, ChiZine, and Clarkesworld, among other places. She lives in northern California and has a standard issue tie-dyed T-shirt to prove it.