ICE - Slicing Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ice Dynamics and Stability Analysis of the Ice Shelf-Glacial System on the East Antarctic Peninsula Over the Past Half Century: Multi-Sensor

Ice dynamics and stability analysis of the ice shelf-glacial system on the east Antarctic Peninsula over the past half century: multi-sensor observations and numerical modeling A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geography & Geographic Information Science of the College of Arts and Sciences by Shujie Wang B.S., GIS, Sun Yat-sen University, China, 2010 M.A., GIS, Sun Yat-sen University, China, 2012 Committee Chair: Hongxing Liu, Ph.D. March 2018 ABSTRACT The flow dynamics and mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet are intricately linked with the global climate change and sea level rise. The dynamics of the ice shelf – glacial systems are particularly important for dominating the mass balance state of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. The flow velocity fields of outlet glaciers and ice streams dictate the ice discharge rate from the interior ice sheet into the ocean system. One of the vital controls that affect the flow dynamics of the outlet glaciers is the stability of the peripheral ice shelves. It is essential to quantitatively analyze the interconnections between ice shelves and outlet glaciers and the destabilization process of ice shelves in the context of climate warming. This research aims to examine the evolving dynamics and the instability development of the Larsen Ice Shelf – glacial system in the east Antarctic Peninsula, which is a dramatically changing area under the influence of rapid regional warming in recent decades. Previous studies regarding the flow dynamics of the Larsen Ice Shelf – glacial system are limited to some specific sites over a few time periods. -

A Multidecadal Analysis of Föhn Winds Over Larsen C Ice Shelf from a Combination of Observations and Modeling

atmosphere Article A Multidecadal Analysis of Föhn Winds over Larsen C Ice Shelf from a Combination of Observations and Modeling Jasper M. Wiesenekker *, Peter Kuipers Munneke, Michiel R. van den Broeke ID and C. J. P. Paul Smeets Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, Utrecht University, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands; [email protected] (P.K.M.); [email protected] (M.R.v.d.B.); [email protected] (C.J.P.P.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.M.W.); Tel.: +31-30-253-3275 Received: 3 April 2018; Accepted: 2 May 2018; Published: 5 May 2018 Abstract: The southward progression of ice shelf collapse in the Antarctic Peninsula is partially attributed to a strengthening of the circumpolar westerlies and the associated increase in föhn conditions over its eastern ice shelves. We used observations from an automatic weather station at Cabinet Inlet on the northern Larsen C ice shelf between 25 November 2014 and 31 December 2016 to describe föhn dynamics. Observed föhn frequency was compared to the latest version of the regional climate model RACMO2.3p2, run over the Antarctic Peninsula at 5.5-km horizontal resolution. A föhn identification scheme based on observed wind conditions was employed to check for model biases in föhn representation. Seasonal variation in total föhn event duration was resolved with sufficient skill. The analysis was extended to the model period (1979–2016) to obtain a multidecadal perspective of föhn occurrence over Larsen C ice shelf. Föhn occurrence at Cabinet Inlet strongly correlates with near-surface air temperature, and both are found to relate strongly to the location and strength of the Amundsen Sea Low. -

Larsen C's Big Divide

NASA A massive rift is splitting the Larsen C ice shelf, which covers 50,000 square kilometres of the Antarctic Peninsula with ice up to 350 metres thick. GLACIOLOGY Larsen C’s big divide Collapse of nearby Antarctic ice shelves offers a glimpse of the future. BY JEFF TOLLEFSON Satellite data collected after the collapse of Since Larsen B’s collapse, ice-sheet model- Larsen B largely settled the debate1,2. The speed lers have tweaked their simulations to better massive crack in Antarctica’s fourth- at which glaciers connected to Larsen A and B reflect the forces driving glacial flow and to biggest ice shelf has surged forward flowed to the sea increased — by up to a factor help to quantify this corking effect — bolstering by at least 10 kilometres since early of eight — after those ice shelves disintegrated, confidence that limited observations from the AJanuary. Scientists who have been monitoring says Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the University Larsen shelves could be applied more broadly. the 175-kilometre rift in the Larsen C ice shelf of California, Irvine. “Some of [the glaciers] have Researchers are now looking back to the say that it could reach the ocean within weeks slowed down a little bit, but they are still flowing history of Larsen A and B (see ‘Cracking up’) or months, releasing an iceberg twice the size five times faster than before,” he notes. Khazen- to understand what the future might hold for of Luxembourg into the Weddell Sea. dar and his colleagues have also found that two Larsen C, which covers 50,000 square kilome- The plight of Larsen C is another sign that glaciers flowing into Larsen B started to acceler- tres with ice up to 350 metres thick. -

Biogeochemistry of a Low-Activity Cold Seep in the Larsen B Area Biogeochemistry of a Low-Activity Cold H

Biogeosciences Discuss., 6, 5741–5769, 2009 Biogeosciences www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/6/5741/2009/ Discussions BGD © Author(s) 2009. This work is distributed under 6, 5741–5769, 2009 the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Biogeosciences Discussions is the access reviewed discussion forum of Biogeosciences Biogeochemistry of a low-activity cold seep in the Larsen B area Biogeochemistry of a low-activity cold H. Niemann et al. seep in the Larsen B area, western Weddell Sea, Antarctica Title Page Abstract Introduction 1,2 3 4 1 5 4,6 H. Niemann , D. Fischer , D. Graffe , K. Knittel , A. Montiel , O. Heilmayer , Conclusions References K. Nothen¨ 4, T. Pape3, S. Kasten4, G. Bohrmann3, A. Boetius1,4, and J. Gutt4 Tables Figures 1Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany 2Institute for Environmental Geosciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland J I 3MARUM, University of Bremen, Germany 4 Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany J I 5Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas, Chile Back Close 6International Bureau of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany, Bonn, Germany Full Screen / Esc Received: 29 May 2009 – Accepted: 9 June 2009 – Published: 18 June 2009 Printer-friendly Version Correspondence to: H. Niemann ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Interactive Discussion 5741 Abstract BGD First videographic indication of an Antarctic cold seep ecosystem was recently obtained from the collapsed Larsen B ice shelf, western Weddell Sea (Domack et al., 2005). 6, 5741–5769, 2009 Within the framework of the R/V Polarstern expedition ANTXXIII-8, we revisited this 5 area for geochemical, microbiological and further videographical examinations. -

An Early Warning Sign of Critical Transition in the Antarctic

1 An Early Warning Sign of Critical Transition in 2 The Antarctic Ice Sheet - 3 A New Data Driven Tool for Spatiotemporal Tipping Point 1,2 1,2 4 Abd AlRahman AlMomani and Erik Bollt 1 5 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Clarkson University, Potsdam, NY 6 13699, USA 2 3 2 7 Clarkson Center for Complex Systems Science (C S ), Potsdam, NY 13699, USA 8 Abstract 9 This paper newly introduces that the use of our recently developed tool, that was originally designed 10 for data-driven discovery of coherent sets in fluidic systems, can in fact be used to indicate early warning 11 signs of critical transitions in ice shelves, from remote sensing data. Our approach adopts a directed 12 spectral clustering methodology in terms of developing an asymmetric affinity matrix and the associated 13 directed graph Laplacian. Specifically, we applied our approach to reprocessing the ice velocity data 14 and remote sensing satellite images of the Larsen C ice shelf. Our results allow us to (post-cast) predict 15 historical events from historical data (such benchmarking using data from the past to forecast events that 16 are now also in the past is sometimes called \post-casting," analogously to forecasting into the future) 17 fault lines responsible for the critical transitions leading to the break up of the Larsen C ice shelf crack, 18 which resulted in the A68 iceberg. Our method indicates the coming crisis months before the actual 19 occurrence, and furthermore, much earlier than any other previously available methodology, particularly 20 those based on interferometry. -

Observing the Antarctic Ice Sheet Using the Radarsat-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar1

OBSERVING THE ANTARCTIC ICE SHEET USING THE RADARSAT-1 SYNTHETIC APERTURE RADAR1 Kenneth C. Jezek Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210 Abstract: This paper discusses the RADARSAT-1 Antarctic Mapping Project (RAMP). RAMP is a collaboration between NASA and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) to map Antarctica using the RADARSAT -1 synthetic aperture radar. The project was conducted in two parts. The first part, which had the data acquisition phase in 1997, resulted in the first high-resolution radar map of Antarctica. The second part, which occurred in 2000, remapped the continent below 80°S Latitude and is now using interfer- ometric repeat-pass observations to compute glacier surface velocities. Project goals and objectives are reviewed here along with several science highlights. These highlights include observations of ice sheet margin change using both RAMP and historical data sets and the derivation of surface velocities on an East Antarctic outlet glacier using interferometric data collected in 2000. INTRODUCTION Carried aloft by a NASA rocket launched from Vandenburg Air Force Base on November 4, 1995, the Canadian RADARSAT-1 is equipped with a C-band (5.3 GHz) synthetic aperture radar (SAR) capable of acquiring high-resolution (25 m) images of the Earth’s surface day or night and under all weather conditions. Along with the attributes familiar to researchers working with SAR data from the European Space Agency’s Earth Remote Sensing Satellite and ENVISAT as well as the Japa- nese Earth Resources Satellite, RADARSAT-1 has enhanced flexibility to collect data using a variety of swath widths, incidence angles, and resolutions. -

Your Cruise the Weddell Sea & Larsen Ice Shelf

The Weddell Sea & Larsen Ice Shelf From 11/19/2021 From Punta Arenas Ship: LE COMMANDANT CHARCOT to 11/30/2021 to Punta Arenas Insurmountable, extreme and captivating: this is the best way to describe the Weddell Sea, mostly frozen by a thick and compressed ice floe. It is a challenge and a privilege to sail on it, with its promiseexceptional of landscapes and original encounters. As you advance across this immense polar expanse, you will enter an infinite ice desert, a world of silence where there is nothing but calm and serenity. To the northwest of the Weddell Sea, stretching along the eastern coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, stands an imposing ice shelf known as the Larsen Ice Shelf. An extension of the ice sheet onto the sea, this white giant is equally disturbing and fascinating, if only due to its colossal dimensions and the impressive table top icebergs - amongst the largest ever seen - that it generates. Overnight in Santiago + flight Santiago/Punta Arenas + transfers + flight Punta Arenas/Santiago This voyage will be an opportunity to come as close as possible to the Weddell Sea, a real refuge for wildlife. We are privileged guests in these extreme lands where we are at the mercy of weather and ice conditions. Our navigation will be determined by the type of ice we come across; as the coastal ice must be preserved, we will take this factor into account from day to day in our itineraries. The sailing schedule and any landings, activities and wildlife encounters are subject to weather and ice conditions. -

The Larsen Ice Shelf System, Antarctica

22–25 Sept. GSA 2019 Annual Meeting & Exposition VOL. 29, NO. 8 | AUGUST 2019 The Larsen Ice Shelf System, Antarctica (LARISSA): Polar Systems Bound Together, Changing Fast The Larsen Ice Shelf System, Antarctica (LARISSA): Polar Systems Bound Together, Changing Fast Julia S. Wellner, University of Houston, Dept. of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Science & Research Building 1, 3507 Cullen Blvd., Room 214, Houston, Texas 77204-5008, USA; Ted Scambos, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado 80303, USA; Eugene W. Domack*, College of Marine Science, University of South Florida, 140 7th Avenue South, St. Petersburg, Florida 33701-1567, USA; Maria Vernet, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, 8622 Kennel Way, La Jolla, California 92037, USA; Amy Leventer, Colgate University, 421 Ho Science Center, 13 Oak Drive, Hamilton, New York 13346, USA; Greg Balco, Berkeley Geochronology Center, 2455 Ridge Road, Berkeley , California 94709, USA; Stefanie Brachfeld, Montclair State University, 1 Normal Avenue, Montclair, New Jersey 07043, USA; Mattias R. Cape, University of Washington, School of Oceanography, Box 357940, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA; Bruce Huber, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, 61 US-9W, Palisades, New York 10964, USA; Scott Ishman, Southern Illinois University, 1263 Lincoln Drive, Carbondale, Illinois 62901, USA; Michael L. McCormick, Hamilton College, 198 College Hill Road, Clinton, New York 13323, USA; Ellen Mosley-Thompson, Dept. of Geography, Ohio State University, 1036 Derby Hall, 154 North Oval Mall, Columbus, Ohio 43210, USA; Erin C. Pettit#, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Dept. of Geosciences, 900 Yukon Drive, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA; Craig R. -

Biogeochemistry of a Low-Activity Cold Seep in the Larsen B Area, Western Weddell Sea, Antarctica

Biogeosciences, 6, 2383–2395, 2009 www.biogeosciences.net/6/2383/2009/ Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2009. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Biogeochemistry of a low-activity cold seep in the Larsen B area, western Weddell Sea, Antarctica H. Niemann1,2, D. Fischer3, D. Graffe4, K. Knittel1, A. Montiel5, O. Heilmayer4,6, K. Nothen¨ 4, T. Pape3, S. Kasten4, G. Bohrmann3, A. Boetius1,4, and J. Gutt4 1Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany 2Institute for Environmental Geosciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland 3MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Department of Geosciences, Univ. of Bremen, Bremen, Germany 4Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany 5Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas, Chile 6German Aerospace Centre, Bonn, Germany Received: 29 May 2009 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 18 June 2009 Revised: 6 October 2009 – Accepted: 7 October 2009 – Published: 2 November 2009 Abstract. First videographic indication of an Antarctic cold 1 Introduction seep ecosystem was recently obtained from the collapsed Larsen B ice shelf, western Weddell Sea (Domack et al., Ocean research of the last decade has provided evidence 2005). Within the framework of the R/V Polarstern expe- for a variety of fascinating ecosystems associated with fluid, dition ANTXXIII-8, we revisited this area for geochemical, gas and mud escape structures. These so-called cold seeps microbiological and further videographical examinations. are often colonized by thiotrophic bacterial mats, chemosyn- During two dives with ROV Cherokee (MARUM, Bremen), thetic fauna and associated animals (Jørgensen and Boetius, several bivalve shell agglomerations of the seep-associated, 2007). -

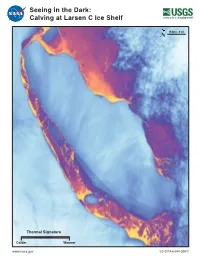

Seeing in the Dark: Calving at Larsen C Ice Shelf

Seeing in the Dark: Calving at Larsen C Ice Shelf 15 km (~9 mi) N Thermal Signature Colder Warmer www.nasa.gov LG-2019-6-394-GSFC Landsat Tracks Calving of Iceberg A-68 Evolving over many years, a massive rift in Antarctica’s Larsen C ice shelf created Iceberg A-68 with an area larger than the State of A-68B Delaware. Observed by Landsat 8’s visible and thermal bands, the Weddell crack could be seen gradually extending at first and then more rapidly in Rift Sea 2016 and early 2017. Due to the onset of Antarctica’s winter darkness, forming visible sensors could no longer track the position of the rift as it grew A-68A closer to the Larsen C’s northern ice front. Landsat 8’s Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) could ‘see’ by capturing the thermal energy emitted by the cold ice shelf and the relatively warmer water and mélange in the narrow rift and the surrounding water of the Weddell Sea. By July 12, 2017, both Landsat 8 TIRS thermal and Sentinel-1 radar imagery confirmed the calving of the ~5800 km2 iceberg. Landsat continued to track this huge iceberg as a piece of A-68 broke off to form the main iceberg, A-68A, and a smaller piece, A-68B. Using Landsat to Monitor the Antarctic N 15 km (~9 mi) Since the first Landsat satellite was launched in 1972, the orbit of July 11, 2016 July 30, 2017 Sept. 16, 2017 these satellites (covering ~83°N to ~83°S latitudes) and their evolving Larsen C Cryospheric scientists had been tracking a crack spreading across the sensors have enabled the tracking of large iceberg calving events in Ice Shelf considerable spatial and temporal detail. -

Configuration of the Northern Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet at LGM Based on a New Synthesis of Seabed Imagery

The Cryosphere, 9, 613–629, 2015 www.the-cryosphere.net/9/613/2015/ doi:10.5194/tc-9-613-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Configuration of the Northern Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet at LGM based on a new synthesis of seabed imagery C. Lavoie1,2, E. W. Domack3, E. C. Pettit4, T. A. Scambos5, R. D. Larter6, H.-W. Schenke7, K. C. Yoo8, J. Gutt7, J. Wellner9, M. Canals10, J. B. Anderson11, and D. Amblas10 1Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale (OGS), Borgo Grotta Gigante, Sgonico, 34010, Italy 2Department of Geosciences/CESAM, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, 3810-193, Portugal 3College of Marine Science, University of South Florida, St. Petersburg, Florida 33701, USA 4Department of Geosciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA 5National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309, USA 6British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, CB3 0ET, UK 7Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, 27568, Germany 8Korean Polar Research Institute, Incheon, 406-840, Republic of Korea 9Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Houston, Houston, Texas 77204, USA 10Departament d’Estratigrafia, Paleontologia i Geociències Marines/GRR Marine Geosciences, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona 08028, Spain 11Department of Earth Science, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77251, USA Correspondence to: C. Lavoie ([email protected]) or E. W. Domack ([email protected]) Received: 13 September 2014 – Published in The Cryosphere Discuss.: 15 October 2014 Revised: 18 February 2015 – Accepted: 9 March 2015 – Published: 1 April 2015 Abstract. We present a new seafloor map for the northern centered on the continental shelf at LGM. -

Coastal-Change and Glaciological Map of the Larsen Ice Shelf Area, Antarctica: 1940–2005

Prepared in cooperation with the British Antarctic Survey, the Scott Polar Research Institute, and the Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie Coastal-Change and Glaciological Map of the Larsen Ice Shelf Area, Antarctica: 1940–2005 By Jane G. Ferrigno, Alison J. Cook, Amy M. Mathie, Richard S. Williams, Jr., Charles Swithinbank, Kevin M. Foley, Adrian J. Fox, Janet W. Thomson, and Jörn Sievers Pamphlet to accompany Geologic Investigations Series Map I–2600–B 2008 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Ferrigno, J.G., Cook, A.J., Mathie, A.M., Williams, R.S., Jr., Swithinbank, Charles, Foley, K.M., Fox, A.J., Thomson, J.W., and Sievers, Jörn, 2008, Coastal-change and glaciological map of the Larsen Ice Shelf area, Antarctica: 1940– 2005: U.S. Geological Survey Geologic Investigations Series Map I–2600–B, 1 map sheet, 28-p.