That Jazz and Blues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

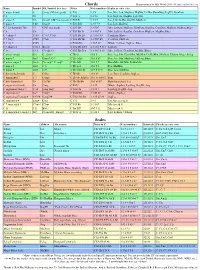

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

The Blues Blue

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 56 A grammatical Conundrum the blues Using “blue” and “the blues” Glossary to denote sadness is not recent BACKBEAT—a rhythmic emphasis on the second and fourth beats of a measure. English slang. The word blue BAR—a musical measure, which is a repeated rhythmic pattern of several beats, usually four quarter notes (4/4) for the blues. The blues usually has twelve bars per was associated with sadness verse. and melancholia in Eliza- BLUE NOTE—the slight lowering downward, usually of the third or seventh notes, of a major scale. Some blues musicians, especially singers, guitarists and bethan England. The Ameri- harmonica players, bend notes upward to reach the blue note. can writer Washington Irving CHOPS—the various patterns that a musician plays, including basic scales. When blues musicians get together for jam sessions, players of the same instrument used the term the blues in sometimes engage in musical duels in front of a rhythm section to see who has the “hottest chops” (plays best). 1807. Grammatically speak- CHORD—a combination of notes played at the same time. ing, however, the term the CHORD PROGRESSION—the use of a series of chords over a song verse that is repeated for each verse. blues is a conundrum: should FIELD HOLLERS—songs that African-Americans sang as they worked, first as it be treated grammatically slaves, then as freed laborers, in which the workers would sing a phrase in response to a line sung by the song leader. as a singular or plural noun? GOSPEL MUSIC—a style of religious music heard in some black churches that The Merriam-Webster una- contains call-and-response arrangements similar to field hollers. -

Blues Poetry As a Celebration of African American Folk Art

ABSTRACT RUTTER, EMILY R. Blues-Inspired Poetry: Jean Toomer, Sterling Brown and the BLKARTSOUTH Collective. (Under the direction of Professor Thomas Lisk). Adopting the blues to lyric poetry marks an implicit rejection of the conventions of the Anglo-American literary establishment, and asserts that African American folk traditions are an equally valuable source of poetic inspiration. During the Harlem Renaissance, Jean Toomer’s Cane (1923) exemplified the incorporation of African American folk forms such as the blues with conventional English poetics. His contemporary Sterling Brown similarly created hybrid forms in Southern Road (1932) that combined African American oral and aural traditions with Anglo-American ones. These texts suggest that blues music represents a complex and sophisticated lyrical form, and its thematic tropes poignantly express the history and contemporary realities of black Americans. In the late 1960s, members of New Orleans’s BLKARTSOUTH were influenced by African American musical traditions as a reflection of historical experience and lyrical expression, and their poetry emphasizes the importance of the blues. Led by Kalamu Ya Salaam and Tom Dent, these poets were part of the Black Arts Movement whose political objectives emphasized a separation from the conventions of the Anglo-American literary establishment, and their work suggests a rejection of traditional English poetics. Although they did not openly acknowledge their literary debt to Toomer and Brown, Cane and Southern Road laid the lyrical foundation for the blues-inspired poetry of Salaam, Dent and their colleagues. What unites these generations of poets is their adoption of the blues theme of resilience in response to the social, political and cultural issues of their eras. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Minor Pentatonic & Blues- the Five Box Shapes

Minor Pentatonic & Blues- The Five Box Shapes Now we will add one note to the minor pentatonic scale and turn it into the six-note blues scale. Pentatonic & Blues scales are the most commonly used scales in most genres of music. We can add the flat 5, (b5), or blue note to the pentatonic scale, making it a six-note scale called the Blues Scale. That b5, or blue note, adds a lot of tension and color to the scale. These are “must-know” scales especially for blues and rock so be sure to memorize them and add them to your soloing repertoire. Most of the time when soloing with minor pentatonic scales you can also use the blues scale. To be safe, at first, use the blue note more in passing for color, don’t hang on it too long. Hanging on that flat five too long can sound a bit dissonant. It’s a great note though, so experiment with it and let your ear guide you. The five box shapes illustrated below cover the entire neck. These five positions are the architecture to build licks and runs as well as to connect into longer expanded scales. To work freely across the entire neck you will want to memorize all five positions as well as the two expanded scales illustrated on the next page. These scale shapes are moveable. The key is determined by the root notes illustrated in black. If you want to solo in G minor pentatonic play box #1 using your first finger starting at the 3rd fret on the low E-string and play the shape from there. -

The Harlem Renaissance

THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE P&L 863-Rama Ndiaye[Type text] Page 1 Curriculum Development Project OVERVIEW The Harlem Renaissance was a period in which black intellectuals, poets, musicians and writers explored their cultural identity. In a society where racism was prevalent African Americans lacked economic opportunities. The creation of art, music and poetry was not only a way to economically uplift the race but also to demonstrate racial pride. The cultural movement started at the end of the First World War and ended in the middle of the Great Depression in the 1930s. Many argue that the War expanded economic opportunity in Northern cities because of industrialization and the decrease of European immigrants coming into the United States. The Great Migration in the beginning of the 20th century also played a big role in the birth of the cultural movement. African Americans in the South were experiencing social, cultural and economic oppression so when they found opportunities to escape Jim Crow laws they took their chances. The lack of a political voice and the prevalent racial hatred led many African Americans to express themselves via artistic means. Alain Locke, an African American writer, was the first to come up with the term “New Negro” talking about a spur of young black artist who were going to change the African American culture by demonstrating that their people were not subservient, good for nothing cretins. Other intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson aided in the expansion of the movement by being spokespeople for the literary youth. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Hollywood, Urban Primitivism, and St. Louis Blues, 1929-1937

An Excursion into the Lower Depths: Hollywood, Urban Primitivism, and St. Louis Blues, 1929-1937 Peter Stanfield Cinema Journal, 41, Number 2, Winter 2002, pp. 84-108 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press DOI: 10.1353/cj.2002.0004 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cj/summary/v041/41.2stanfield.html Access Provided by Amherst College at 09/03/11 7:59PM GMT An Excursion into the Lower Depths: Hollywood, Urban Primitivism, and St. Louis Blues, 1929–1937 by Peter Stanfield This essay considers how Hollywood presented the song St. Louis Blues in a num- ber of movies during the early to mid-1930s. It argues that the tune’s history and accumulated use in films enabled Hollywood to employ it in an increasingly com- plex manner to evoke essential questions about female sexuality, class, and race. Recent critical writing on American cinema has focused attention on the struc- tures of racial coding of gender and on the ways in which moral transgressions are routinely characterized as “black.” As Eric Lott points out in his analysis of race and film noir: “Raced metaphors in popular life are as indispensable and invisible as the colored bodies who give rise to and move in the shadows of those usages.” Lott aims to “enlarge the frame” of work conducted by Toni Morrison and Ken- neth Warren on how “racial tropes and the presence of African Americans have shaped the sense and structure of American cultural products that seem to have nothing to do with race.”1 Specifically, Lott builds on Manthia D iawara’s argument that “film is noir if it puts into play light and dark in order to exhibit a people who become ‘black’ because of their ‘shady’ moral behaviour.2 E. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive.