Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAMES THIS WEEK Morgan State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-2 .000 15 109 0-0 0-2 0-0 Lost 2 *Florida A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 1-1 .500 57 82 1-0 0-1 0-0 Won 1 SATURDAY (SEPT

WEEK 4 SEPT. 21 2019 FOOTBALL NOTES MID-EASTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE 292 NFL DRAFT SELECTIONS | 12 NFL HALL OF FAMERS | 49 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE STANDINGS MEAC MEDIA CONTACT Maurice Williams, Assistant Team MEAC Pct. PF PA Total Pct. PF PA H A N Streak Commissioner for Media Relations South Carolina State 0-0 .000 0 0 2-1 .667 78 68 2-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 Email: [email protected] North Carolina A&T State 0-0 .000 0 0 2-1 .667 64 87 1-0 1-1 0-0 Won 1 Phone: 757-951-2055 Delaware State 0-0 .000 0 0 1-1 .500 71 43 1-0 0-1 0-0 Won 1 Bethune-Cookman 0-0 .000 0 0 1-1 .500 36 78 0-0 0-1 1-0 Lost 1 Norfolk State 0-0 .000 0 0 1-2 .333 72 91 1-0 0-2 0-0 Lost 1 Howard 0-0 .000 0 0 0-3 .000 48 174 0-0 0-2 0-1 Lost 3 N.C. Central 0-0 .000 0 0 0-3 .000 25 104 0-0 0-3 0-0 Lost 3 GAMES THIS WEEK Morgan State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-2 .000 15 109 0-0 0-2 0-0 Lost 2 *Florida A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 1-1 .500 57 82 1-0 0-1 0-0 Won 1 SATURDAY (SEPT. 21) * - Ineligible for MEAC Championship & Postseason Morgan State at Army 12 p.m. Television: CBS Sports Network Series: Army lead 2-0 Last Meeting: Nov. -

PREVIEW First Section 2

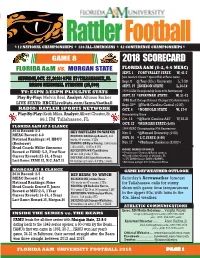

FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY / RATTLERS / FOOTBALL Rattler Football * 12 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS * 130 ALL-AMERICANS * 42 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS * GAME 8 2018 SCORECARD FLORIDA A&M vs. MORGAN STATE FLORIDA A&M (5-2, 4-0 MEAC) SEPT. 1 FORT VALLEY STATE W, 41-7 SATURDAY, OCT. 27, 2018 / 4 PM ET / TALLAHASSEE, FL Jake Gaither Classic * Sports Hall of Fame Game Sept. 8 @ Troy (Ala.) University L, 7-59 BRAGG MEMORIAL STADIUM (25,500) SEPT. 15 JACKSON STATE L,16-18 TV: ESPN 3/ESPN PLUS/LIVE STATS 1978 NCAA Championship Team 40th Anniversary Play-By-Play: Melvin Beal. Analyst: Alfonso Barber SEPT. 22 *SAVANNAH STATE W, 31-13 1998 Black College National Champs 20th Anniversary LIVE STATS: HBCULiveStats.com/famu/football Sept. 29 * @North Carolina Central (4:00) RADIO: RATLER SPORTS NETWORK OCT. 6 *NORFOLK STATE W, 17-0 Play-By-Play: Keith Miles. Analyst: Albert Chester, Sr. Homecoming Game 96.1 FM Tallahassee, FL Oct. 13 *@North Carolina A&T W, 22-21 OCT. 27 *MORGAN STATE (4:00) FLORIDA A&M AT A GLANCE 1988 MEAC Championship 30th Anniversary 2018 Record: 5-2 KEY RATTLERS TO WATCH Nov. 3 *@Howard University (1:00) MEAC Record: 4-0 RUSHING: RB Bishop Bonnett, 343 NOV. 10 * S.C.STATE (4:00) National Rankings: #1 HBCU yards, 43 carries, 3 TDs (Boxtorow) PASSING: QB Ryan Stanley, 1,545 yards, Nov. 17 *#Bethune-Cookman (2:00)% Head Coach: Willie Simmons (122 of 202), 10 TDs, 6 INT RECEIVING: WR Chad Hunter HOME GAMES IN BOLD Record at FAMU: 5-2, First Year *Conference Games; @Away games; 32 rec, 446 yards, 5 TDs Career Record: 27-13, 4 Years #Florida Blue Classic at Orlando, FL DEFENSE: LB Elijah Richardson, %-TV ESPNClassic/ESPN3/ESPNU; Last Game: FAMU 22, N.C. -

CONFERENCE NOTES Sunday, January 24 Delaware State at Old Dominion, 3 P.M

MEAC VOLLEYBALL NOTES | WEEK 1 WEEK 1 - 1/18-1/24 2020-21 VOLLEYBALL NOTES MID-EASTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE A GOLDEN PAST, A GLORIOUS FUTURE STANDINGS NORTHERN DIVISION Team MEAC Pct. Overall Pct. 3-Set 4-Set 5-Set Hm Rd Neu Last 10 Streak Coppin State 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- Delaware State 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- Howard 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- Morgan State 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- SOUTHERN DIVISION Team MEAC Pct. Overall Pct. 3-Set 4-Set 5-Set Hm Rd Neu Last 10 Streak Norfolk State 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- North Carolina A&T 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- N.C. Central 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- South Carolina State 0-0 .000 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- *Bethune-Cookman, Florida A&M and Maryland Eastern Shore have opted out of competition for the 2020 season GAMES THIS WEEK CONFERENCE NOTES Sunday, January 24 Delaware State at Old Dominion, 3 p.m. -

2016-17 Hampton University Men's Basketball

Men’s Basketball Quick Facts Location ........................................................................................... Hampton, Va. Enrollment ......................................................................................................4,768 2016-17 Hampton University Conference ......................................................................Mid-Eastern Athletic ..................................................................................NCAA Division I Arena ................................................................Hampton Convocation Center Men’s Basketball AffiliationNickname .................................................................................................... Pirates President .........................................................................Dr. William R. Harvey Athletic Director ..............................................................Eugene Marshall, Jr. Game #29 - March 3, 2017 Hampton vs. Coppin State Head Coach ............................................................................ Edward Joyner, Jr. Sports Information Director • Maurice Williams • Men’s Basketball Contact Record at Hampton ...............................................................................133-122 [email protected] • Office (757) 727-5757 Hampton (13-15, 10-5 MEAC) vs. 2016-17 Men’s Basketball Coppin State (8-22, 7-8 MEAC) Schedule and Results Physical Education Complex • Baltimore, Md. Date Opponent Time/Result Record Thursday, March 2, 2017 • 7:30 p.m. (EST) NOVEMBER -

Norfolk State Women's Basketball

NORFOLK STATE GAME 23 | ROAD GAME 12 MONDAY, FEB. 11 | 4 P.M. WOMEN’S BASKETBALL TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA 2018-19 GAME NOTES AL LAWSON CENTER 2018-19 Schedule/Results NORFOLK STATE SPARTANS (11-11, 6-3 MEAC) (11-11, 6-3 MEAC) HEAD COACH: LARRY VICKERS (NORFOLK STATE ‘07) RECORD AT NSU: 47-45 (FOURTH SEASON) November (3-4) CAREER RECORD: SAME Tue. 6 Ole Miss ............................... L, 60-42 Fri. 9 Old Dominion........................ L, 69-53 RECORD VS. FLORIDA A&M: 2-2 Tue. 13 Cheyney ............................. W, 93-40 Sun. 18 Navy .................................... W, 65-58 FLORIDA A&M LADY RATTLERS (3-19, 1-9 MEAC) Tue. 20 Campbell ............................. L, 57-49 HEAD COACH: LeDAWN GIBSON (WARNER SOUTHERN ‘00) Sat. 24 Lehigh!.................................. L, 62-41 RECORD AT FAMU: 144-183 (11TH SEASON) Sun. 25 Liberty!................................. W, 66-53 CAREER RECORD: SAME December (2-4) RECORD VS. NORFOLK STATE: 9-4 Sun. 9 La Salle ................................ L, 62-52 Wed. 12 Longwood .......................... W, 74-42 The Opening Tip: Bethune-Cookman outscored Norfolk Sat. 15 High Point ............................. L, 83-51 State 23-9 over the final 6:10 of the game to erase a 49- GAME CENTER Date: Monday, Feb. 11 Tue. 18 St. Augustine’s .................. W, 71-38 42 deficit en route to a 65-58 win inside Moore Gymnasi- Fri. 21 William & Mary .................... L, 55-44 um on Saturday afternoon. The Lady Wildcats rallied off Time: 4 p.m. Sun. 30 Wake Forest ......................... L, 63-61 14-unanswered during the run to turn a seven-point deficit Site: Tallahassee, Fla. into a seven-point advantage. -

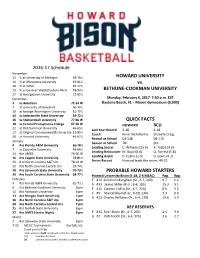

2016-17 Schedule HOWARD UNIVERSITY Vs. BETHUNE

2016-17 Schedule November 11 % at University of Michigan 58-76 L HOWARD UNIVERSITY 14 % at Marquette University 49-81 L vs. 18 % at IUPUI 55-77 L 19 % vs Gardner Webb/Eastern Mich. 78-94 L BETHUNE-COOKMAN UNIVERSITY 27 at Georgetown University 72-85 L December Monday, February 6, 2017 7:30 p.m. EST 3 vs American 71-54 W Daytona Beach, FL – Moore Gymnasium (3,000) 7 at University of Maryland 56-79 L 10 at George Washington University 62-79 L 14 vs Jacksonville State University 59-72 L 16 vs Shenandoah University 77-66 W QUICK FACTS 18 vs Central Pennsylvania College 67-60 W HOWARD BCU 22 at Old Dominion University 46-65 L Last Year Record 5-18 4-18 27 at Virginia Commonwealth University 51-85 L Coach Kevin Nickelberry Gravelle Craig 30 at Harvard University 46-67 L ;30 Record at School 64-148 68-119 January Season at School 7th 6th 4 #vs Florida A&M University 66-78 L Leading Scorer C. Williams (15.6) B. Tabb (19.6) 7 at Columbia University 48-66 L Leading Rebounder M. Boyd (6.6) Q. Forrest (5.8) 14 #at UMES 74-66 W 16 #vs Coppin State University 72-81 L Leading Assist D. Collins (2.0) D. Lewis (4.2) 21 # at North Carolina A&T Uni. 78-63 W Series Record Howard leads the series, 44-22. 23 #at North Carolina Central Uni. 39-74 L 28 #vs Savannah State University 70-73 L PROBABLE HOWARD STARTERS 30 #vs South Carolina State University 68-77 L Howard University Bison (5-18, 2-6 MEAC) Ppg. -

CONFERENCE NOTES Wednesday, Nov

MEAC MEN’S BASKETBALL NOTES | WEEK 1 WEEK 1 11/22-30 2020-21 MEN’S BASKETBALL NOTES MID-EASTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE A GOLDEN PAST, A GLORIOUS FUTURE STANDINGS Northern Division Team MEAC Pct. PF PA Total Pct. PF PA HM RD NEU Last 10 Streak Coppin State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - Howard 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - Morgan State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - Norfolk State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - *Delaware State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - * - Ineligible for MEAC Championship & Postseason Southern Division Team MEAC Pct. PF PA Total Pct. PF PA HM RD NEU Last 10 Streak Florida A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - North Carolina Central 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - North Carolina A&T State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - South Carolina State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 - * - Bethune-Cookman and Maryland Eastern Shore have opted-out of competition for the 2020-21 season GAMES THIS WEEK CONFERENCE NOTES Wednesday, Nov. -

GAMES THIS WEEK Morgan State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-1 .000 3 46 0-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 *Florida A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 0-1 .000 0 62 0-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 SATURDAY (SEPT

WEEK 3 SEPT. 14 2019 FOOTBALL NOTES MID-EASTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE 292 NFL DRAFT SELECTIONS | 12 NFL HALL OF FAMERS | 49 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE STANDINGS MEAC MEDIA CONTACT Maurice Williams, Assistant Team MEAC Pct. PF PA Total Pct. PF PA H A N Streak Commissioner for Media Relations South Carolina State 0-0 .000 0 0 2-0 1.000 62 13 2-0 0-0 0-0 Won 2 Email: [email protected] Bethune-Cookman 0-0 .000 0 0 1-0 1.000 36 15 0-0 0-0 1-0 Won 1 Phone: 757-951-2055 Norfolk State 0-0 .000 0 0 1-1 .500 65 45 1-0 0-1 0-0 Won 1 North Carolina A&T State 0-0 .000 0 0 1-1 .500 37 66 1-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 Howard 0-0 .000 0 0 0-2 .000 28 133 0-0 0-2 0-0 Lost 2 N.C. Central 0-0 .000 0 0 0-2 .000 13 83 0-0 0-2 0-0 Lost 2 Delaware State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-1 .000 13 31 0-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 GAMES THIS WEEK Morgan State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-1 .000 3 46 0-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 *Florida A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 0-1 .000 0 62 0-0 0-1 0-0 Lost 1 SATURDAY (SEPT. 14) * - Ineligible for MEAC Championship & Postseason Norfolk State at Coastal Carolina 2 p.m. -

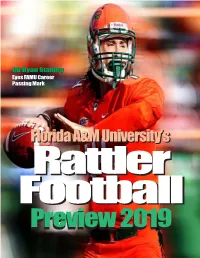

PREVIEW First Section 2

QB Ryan Stanley Eyes FAMU Career Passing Mark FloridaFlorida A&MA&M University’sUniversity’s RattlerRattler FootballFootball PreviewPreview 20192019 FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL 2019 PAGE 1 2019’s Lead Story Ryan Stanley Chasing FAMU’s Greats FAMU senior quarterback Ryan Stanley has two main goals in mind in 2019: (1) to lead FAMU to back-to-back winning seasons for the first time in nearly a decade; (2) to make a run at FAMU’s all-time career pass- ing record. The Pembroke Pines native became the fifth player in FAMU Football history to pass for over 6,000 yards in 2018. A two-time All-Mid-Eastern Athletic Con- ference selection, Stanley needs 1,308 yards to move past Quinn Gray, who passed for 7,378 yards during the height of the Gulf Coast Offensive Era from 1998 to 2001. FAMU Career Passing Leaders 7,378 – Quinn Gray (1998-2001) 6,954 – Damien Fleming (2011-14) 6,838 – Oteman Sampson-Delancy (1996-97) 6,620 – Tony Ezell (1988-91) 6,071 – Ryan Stanley (2016-Present) 5,198 – Ben Doughtery (2003-04) 4,148 – Patrick Bonner (1998) 3,707 – Nathaniel Koonce (1980-82) 2,981 – Stephen Scruggs (1967-70) PAGE 2 FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL 2019 Rattler Football * 12 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS * 130 ALL-AMERICANS * 42 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS * GAME ONE 2019 FAMU SCHEDULE Aug. 29 @ UCF (7:30) FAMU at UCF SEPT. 14 FORT VALLEY STATE (6:00) Thursday, August 29, 2019 #Jake Gaither Classic / Sports Hall of Fame Game Spectrum Stadium (44,206) Orlando, FL * 7:30 p.m * CBS Sports Network SEPT. -

Three Baccalaureate Degrees on 2012 Roster

Three Baccalaureate Degrees on 2012 Roster FAMU Athletics is dedicated The results have been as- Hepburn twice won the Army to its student-athletes, both on and tounding. “We must continue to Strong award last year and is ex- off the field of play. Evidence of show our dedication to our student- pected to have his breakout season. this can be taken from the fact that athletes by providing them with Scott, has been selected for two 40 student-athletes, 15 in football every possible resource to be suc- watch lists in this preseason. The alone, attained their degrees this cessful,” FAMU director of athlet- Stanford University transfer is also past Spring. ics Derek Horne said. an ordained minister. Among the crowd of student- The three graduates will be These three accomplished athletes who walked across the stage enrolled in graduate studies during football players are far from the on Apr.28, were three current mem- the Fall semester. Hartley, received norm in college athletics, but exact- bers of the Rattler Football squad. a bachelor’s degree in Political Sci- ly what the mission of Florida A&M Offensive lineman Robert Hartley, ence, Hepburn acquired a bach- University and FAMU Athletics linebacker Brandon Hepburn and elor’s degree in chemistry and Scott calls for. Congratulations to our ul- nosetackle Padric Scott all met their attained his degree in biology. timate student-athletes for their suc- academic goals. Hartley is a preseason All- cess on and off the field of play. The athletic department made MEAC selection at offensive line. a commitment to the academic suc- cess of it’s student-athletes by devel- oping and staffing the Athletic Aca- demic Center. -

Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference

MID-EASTERN Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference Football Report 2018 Season • Week 1 Contact: Ryan McGinty, Assistant Commissioner for Media Relations ATHLETIC CONFERENCE [email protected] • 757.95112055 292 NFL DRAFT SELECTIONS | 12 NFL HALL OF FAMERS | 48 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE Team MEAC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Hm Rd Neu Streak North Carolina A&T State 0-0 .000 0 0 1-0 1.000 20 17 0-0 0-0 1-0 Won 1 Bethune-Cookman 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Delaware State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Florida A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Howard 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Morgan State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Norfolk State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- North Carolina Central 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Savannah State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- South Carolina State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Saturday, September 29 THIS WEEK 1ST & 10 Thursday, August 30 • The 2018 season kicks off with week one as every MEAC team is in action. -

The Life and Legacy of Frank Terry Greer and His Influences on Historically Black College and University Bands

1 THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF FRANK TERRY GREER AND HIS INFLUENCES ON HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY BANDS BY MICHAEL LLOYD SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE DR. MEGAN M. SHERIDAN, CHAIR DR. MATTHEW D. SCHATT, MEMBER A CAPSTONE PROJECT PRESENTED TO THE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 Running head: FRANK T. GREER 2 Abstract Frank Terry Greer was the second Director of Bands at Tennessee State University from 1951- 1972. During his tenure, he developed the marching band to become the nationally known Aristocrat of Bands. The purpose of this historical study was to preserve the history and accomplishments Greer garnered in his illustrious career. Through the research of historical documents and interviews of a former student of Greer’s and the current Tennessee State band staff, this historical study examined who Frank Greer was, how he challenged the norms of the Historically Black College and University (HBCU) music programs, and how his work at Tennessee State contributed to the history of the school and the evolution of the Aristocrat of Bands. The findings of this study revealed that Greer not only prepared his school, music department, and band to compete with other HBCUs, but also took Tennessee State’s music program to the national stage, placing them in the same realm as the bigger flagship institutions in America. Keywords: Historically Black College and University, HBCU, Tennessee State University, marching band, Aristocrat of Bands FRANK T. GREER 3 The Life and Legacy of Frank Terry Greer and His Influences on Historically Black College and University Bands The band programs, especially the marching bands, are the cornerstones of many Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU).