Forumjournal VOL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies Van Der Rohe Award: a Tribute to Bauhaus

AT A GLANCE EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies van der Rohe Award: A tribute to Bauhaus The EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture (also known as the EU Mies Award) was launched in recognition of the importance and quality of European architecture. Named after German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a figure emblematic of the Bauhaus movement, it aims to promote functionality, simplicity, sustainability and social vision in urban construction. Background Mies van der Rohe was the last director of the Bauhaus school. The official lifespan of the Bauhaus movement in Germany was only fourteen years. It was founded in 1919 as an educational project devoted to all art forms. By 1933, when the Nazi authorities closed the school, it had changed location and director three times. Artists who left continued the work begun in Germany wherever they settled. Recognition by Unesco The Bauhaus movement has influenced architecture all over the world. Unesco has recognised the value of its ideas of sober design, functionalism and social reform as embodied in the original buildings, putting some of the movement's achievements on the World Heritage List. The original buildings located in Weimar (the Former Art School, the Applied Art School and the Haus Am Horn) and Dessau (the Bauhaus Building and the group of seven Masters' Houses) have featured on the list since 1996. Other buildings were added in 2017. The list also comprises the White City of Tel-Aviv. German-Jewish architects fleeing Nazism designed many of its buildings, applying the principles of modernist urban design initiated by Bauhaus. -

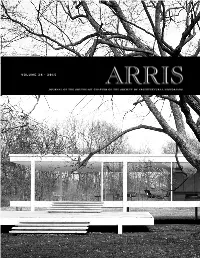

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Modernism's Influence on Architect-Client Relationship

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Architectural and Environmental Engineering Vol:12, No:10, 2018 Modernism’s Influence on Architect-Client Relationship: Comparative Case Studies of Schroder and Farnsworth Houses Omneya Messallam, Sara S. Fouad beliefs in accordance with modern ideas, in the late 19th and Abstract—The Modernist Movement initially flourished in early 20th centuries. Additionally, [2] explained it as France, Holland, Germany and the Soviet Union. Many architects and specialized ideas and methods of modern art, especially in the designers were inspired and followed its principles. Two of its most simple design of buildings of the 1940s, 50s and 60s which important architects (Gerrit Rietveld and Ludwig Mies van de Rohe) were made of modern materials. On the other hand, [3] stated were introduced in this paper. Each did not follow the other’s principles and had their own particular rules; however, they shared that, it has meant so much that it has often meant nothing. the same features of the Modernist International Style, such as Anti- Perhaps, the belief of [3] stemmed from a misunderstanding of historicism, Abstraction, Technology, Function and Internationalism/ the definitions of Modernism, or what might be true is that it Universality. Key Modernist principles translated into high does not have a clear meaning to be understood. Although this expectations, which sometimes did not meet the inhabitants’ movement was first established in Europe and America, it has aspirations of living comfortably; consequently, leading to a conflict become global. Applying Modernist principles on residential and misunderstanding between the designer and their clients’ needs. -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe: Technology and Architecture

1950 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Technology and architecture In 1932 Mies moved to Berlin with the teachers and students ofthe Bauhaus and there continued it as a private institute. In July 1933 it was closed by the Gestapo. In summer 1937 Mieswent tathe USA; in 1938 he received an invitation to the Illinois Institute ofTechnology (liT) in Chicago and a little later was commissioned to redesign the university campus. The first buildings went up in the years 1942-3. They introduced the second great phase ofhis architecture. In 1950 Mies delivered to the liT the speech reproduced here. Technology is rooted in the past. It dominates the present and tends into the future. It is a real historical movement - one of the great movements which shape and represent their epoch. It can be compared only with the Classic discovery of man as a person, the Roman will to power, and the religious movement ofthe Middle Ages. Technology is far more than a method, it is a world in itself. As a method it is superior in almost every respect. But only where it is left to itself, as in gigantic structures of engineering, there tech nology reveals its true nature. There it is evident that it is not only a useful means, but that it is something, something in itself, something that has a meaning and a powerful form - so powerful in fact, that it is not easy to name it. Is that still technology or is it architecture? And that may be the reason why some people are convinced that architecture will be outmoded and replaced by technology. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe. American, Born Germany

LESSON FOUR: Exploring the Design Process 17 L E S S O IMAGE TWELVE: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. IMAGE THIRTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der N American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. S Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Site View of north side. Photo: Hedrich Blessing. and floor plans. Ink on illustration board, 1 The Museum of Modern Art, New York 27 ⁄2 x 20" (69.9 x 50.8 cm). The Mies van der Rohe Archive IMAGE FOURTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der IMAGE FIFTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. North and west elevations. Pencil on ozalid, Model, aerial view of plaza and lower floors. 1 37 ⁄4" x 52" (94.6 x 132.1 cm). Revised Photo: Louis Checkman. The Museum of February 18, 1957. The Mies van der Rohe Modern Art, New York Archive IMAGE SIXTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. IMAGE SEVENTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Construction photograph showing steel View, office interior. Photo: Ezra Stoller. frame. Photo: House of Patria. The Mies van Esto Photographics der Rohe Archive. Gift of the architect IMAGE EIGHTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Brno Chair. 1929–30. Chrome-plated steel and 1 leather, 31 ⁄2 x 23 x 24" (80 x 58.4 x 61 cm). -

Flooded at the Farnsworth House MICHAEL CADWELL the Ohio State University

392 THE ART OF ARCHITECTURE/THE SCIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE Flooded at the Farnsworth House MICHAEL CADWELL The Ohio State University In 1988, nearly twenty years after his mentor’s the means by which this drama unfolded. Duckett’s death, the architect Edward A. Duckett remem- stick and his act of framing recall the central ar- bered an afternoon outing with Mies van der Rohe. chitectural activity of drawing: the stick, now a One time we were out at the Farnsworth House, pencil, describes a frame, now a building, which and Mies and several of us decided to walk down affords a particular view of the world. In this es- to the river’s edge. So we were cutting a path say, I will elaborate on the peculiar intertwining of through the weeds. I was leading and Mies was building, drawing, and nature at the Farnsworth right behind me. Right in front of me I saw a young House; how drawing erases a positivist approach possum. If you take a stick and put it under a young to building technology and how, in turn, a pro- possum’s tail, it will curl its tail around the stick found respect for the natural world deflects and, and you can hold it upside down. So I reached finally, absorbs the unifying thrust of perspective. down, picked up a branch, stuck it under this little possum’s tail and it caught onto it and I turned Approached by Dr. Farnsworth in the winter of around and showed it to Mies. Now, this animal is 1946/7 to design a weekend house, Mies responded thought by many to be one of the world’s ugliest, with uncharacteristic alacrity. -

Forumjournal VOL

ForumJournal VOL. 32, NO. 3 Heritage in the Landscape Contents NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION VOL. 32, NO. 3 PAUL EDMONDSON President & CEO Cultural Landscapes and the National Register KATHERINE MALONE-FRANCE BARBARA WYATT ...............................................3 Chief Preservation Officer TABITHA ALMQUIST Chief Administrative Officer Large-Landscape Conservation: A New Frontier THOMPSON M. MAYES for Cultural Heritage Chief Legal Officer & BRENDA BARRETT ............................................. 13 General Counsel PATRICIA WOODWORTH Honoring and Preserving Hawaiian Cultural Interim Chief Financial Officer Landscapes GEOFF HANDY Chief Marketing Officer BY DAVIANNA PŌMAIKA‘I MCGREGOR .............................22 PRESERVATION Stewarding and Activating the Landscape LEADERSHIP FORUM of the Farnsworth House SUSAN WEST MONTGOMERY SCOTT MEHAFFEY. .30 Vice President, Preservation Resources Tribal Heritage at the Grand Canyon: RHONDA SINCAVAGE Director, Publications and Protecting a Large Ethnographic Landscape Programs to Sustain Living Traditions SANDI BURTSEVA BRIAN R. TURNER .............................................. 41 Content Manager KERRI RUBMAN Assistant Editor Meshing Conservation and Preservation Goals PRIYA CHHAYA with the National Register Associate Director, ELIZABETH DURFEE HENGEN AND JENNIFER GOODMAN .............50 Publications and Programs MARY BUTLER Adapting to Maintain a Timeless Garden at Filoli Creative Director KARA NEWPORT . 61 Cover: Beach Ridges on the Shore of Cape Krusenstern, part of Cape Krusenstern National Monument in Alaska PHOTO COURTESY OF NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Forum Journal, a publication of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (ISSN 1536-1012), is published by the Preservation Resources Department at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2600 Virginia Avenue, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20037 as a benefit of National Trust Forum The National Trust for Historic Preservation works to save America’s historic places for membership. -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center Elizabeth Stoloff Vehse West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Vehse, Elizabeth Stoloff, "Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 848. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/848 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves’s Erickson Alumni Center Elizabeth Stoloff Vehse Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Kristina Olson, M.A., Chair Janet Snyder, Ph.D. -

List of Illinois Recordations Under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (As of April 2021)

List of Illinois Recordations under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (as of April 2021) HABS = Historic American Buildings Survey HAER = Historic American Engineering Record HALS = Historic American Landscapes Survey HIBS = Historic Illinois Building Survey (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey) HIER = Historic Illinois Engineering Record (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Engineering Record) Adams County • Fall Creek Station vicinity, Fall Creek Bridge (HABS IL-267) • Meyer, Lock & Dam 20 Service Bridge Extension Removal (HIER) • Payson, Congregational Church, Park Drive & State Route 96 (HABS IL-265) • Payson, Congregational Church Parsonage (HABS IL-266) • Quincy, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, Freight Office, Second & Broadway Streets (HAER IL-10) • Quincy, Ernest M. Wood Office and Studio, 126 North Eighth Street (HABS IL-339) • Quincy, Governor John Wood House, 425 South Twelfth Street (HABS IL-188) • Quincy, Illinois Soldiers and Sailors’ Home (Illinois Veterans’ Home) (HIBS A-2012-1) • Quincy, Knoyer Farmhouse (HABS IL-246) • Quincy, Quincy Civic Center/Blocks 28 & 39 (HIBS A-1991-1) • Quincy, Quincy College, Francis Hall, 1800 College Avenue (HABS IL-1181) • Quincy, Quincy National Cemetery, Thirty-sixth and Maine Streets (HALS IL-5) • Quincy, St. Mary Hospital, 1415 Broadway (HIBS A-2017-1) • Quincy, Upper Mississippi River 9-Foot Channel Project, Lock & Dam No. 21 (HAER IL-30) • Quincy, Villa Kathrine, 532 Gardner Expressway (HABS IL-338) • Quincy, Washington Park (buildings), Maine, Fourth, Hampshire, & Fifth Streets (HABS IL-1122) Alexander County • Cairo, Cairo Bridge, spanning Ohio River (HAER IL-36) • Cairo, Peter T. Langan House (HABS IL-218) • Cairo, Store Building, 509 Commercial Avenue (HABS IL-25-21) • Fayville, Keating House, U.S.