The Five Guiding Principles a Resource for Study the Five

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westminster Abbey 2013 Report to the Visitor Her Majesty the Queen

Westminster Abbey 2013 Report To The Visitor Her Majesty The Queen Your Majesty, The Dean and Chapter of the Collegiate Church of St Peter in Westminster, under the Charter of Queen Elizabeth I on 21st May 1560 and the Statutes graciously granted us by Your Majesty in a Supplemental Charter on 16th February 2012, is obliged to present an Annual Report to Your Majesty as our Visitor. It is our privilege, as well as our duty, now to present the Dean and Chapter’s Annual Report for the Year of Grace 2013. From time to time, the amount of information and the manner in which it is presented has changed. This year we present the report with more information than in recent years about the wide range of expertise on which the Dean and Chapter is able to draw from volunteers sitting on statutory and non-statutory advisory bodies. We also present more information about our senior staff under the Receiver General and Chapter Clerk who together ensure that the Abbey is managed efficiently and effectively. We believe that the account of the Abbey’s activities in the year 2013 is of wide interest. So we have presented this report in a format which we hope not only the Abbey community of staff, volunteers and regular worshippers but also the wider international public who know and love the Abbey will find attractive. It is our daily prayer and our earnest intention that we shall continue faithfully to fulfil the Abbey’s Mission: — To serve Almighty God as a ‘school of the Lord’s service’ by offering divine worship daily and publicly; — To serve the Sovereign by daily prayer and by a ready response to requests made by or on behalf of Her Majesty; — To serve the nation by fostering the place of true religion within national life, maintaining a close relationship with members of the House of Commons and House of Lords and with others in representative positions; — To serve pilgrims and all other visitors and to maintain a tradition of hospitality. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

THY KINGDOM COME Codes of Conduct

TEAM WORK: PHOTOS: REVD HUW RIDEN HUW REVD PHOTOS: HOW SPORT GOOD NEWS FROM THE DIOCESE OF EXETER | JULY 2019 RUNNING JOHN BELL AT THE RACE HELPS US HOLY GROUND The Right Revd Nick LIVE OUT Iona musician to be special McKinnel reflects on guest at Cathedral service... the number of sport and he has planned the analogies in the New THE GOSPEL music for the Eucharist Testament The Right Revd Members of the re-established Nick McKinnel Exeter Diocesan Cricket Team Bishop of Plymouth That’s true not only for the obvious team sports. t is promising to be a great summer of sport: These days every professional golfer or cyclist has Wimbledon this month, an Ashes series in August, a team behind them. the Rugby World Cup in September hopefully As we know from church life, we are ‘better with a sprinkling of Chiefs’ players in the squad, together’, called into the body of Christ, to work for the prospect of Plymouth Argyle and Exeter City Diocese joins the whole world to feel power of prayer the cause of God’s kingdom. Ibattling out in League Two later in the year. Even the Sport requires order, rules and parameters Diocesan cricket team revived its fortunes in a modest within which a game can be played. These might way! be white lines on a tennis court or long hallowed The glory of sport, whether we watch or play, is THY KINGDOM COME codes of conduct. pitting skill against skill, strength against strength. It is not acceptable that anything goes, that It tests character, brings glory, makes heroes and everyone’s view point is equally valid or that rules rayer has been centre offers hope – think of the English teams trailing can be made up as we go along. -

ISSUE 01 the New Alumni Community Website

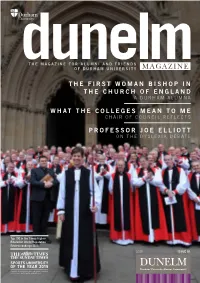

THE MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF DURHAM UNIVERSITY THE FIRST WOMAN BISHOP IN THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND A DURHAM ALUMNA WHAT THE COLLEGES MEAN TO ME CHAIR OF COUNCIL REFLECTS PROFESSOR JOE ELLIOTT ON THE DYSLEXIA DEBATE Top 100 in the Times Higher Education World Reputation Review rankings 2015 2015 ISSUE 01 www.dunelm.org.uk The new alumni community website We’ll be continuing development of the website over the coming months, so do let us know what you think and what you’d like to see there. The alumni community offers useful connections all over the world, with a global events calendar backed by a network of alumni volunteers and associations, combining professional networking and social gatherings with industry-specific workshops and research dissemination. We have major events in cities across the UK and around the world, ranging from formal dinners, grand balls, exclusive receptions and wine tastings, to Christmas carol concerts, sporting events, family days and more. Ads.indd 2 19/03/2015 13:58 ISSUE 01 2015 DUNELM MAGAZINE 3 www.dunelm.org.uk The new alumni community website Welcome to your new alumni magazine. It is particularly gratifying to find a new way to represent the Durham experience. Since I joined the University two and a half years ago, I have been amazed by how multi-faceted it all is. I therefore hope that the new version of this magazine is able to reflect that richness in the same way that Durham First did for so many years. In fact, in order to continue to offer exceptional communication, we have updated your alumni magazine, your website - www.dunelm.org.uk - and your various social media pages. -

January 2015

Our Church is eco-friendly Bishop Allan Scarfe on 2014 Annual Youth Conference “The earth is the Lord’S, and the from page 6….as part of our time there, as well as participate in the Youth Conference. We are fullness thereof: the world, and they grateful too for the care of the people at Thokoza that dwell therein”. and for the friendships we have made, especially net Psalm 24:1 dJanuaryio 2015 issue15 Vol 2 with our translators and drivers. We bring home a new song in our hearts quite literally, as a Seswati song you taught us has ANGLICAN CHURCH DIOCESE OF SWAZILAND NEWS LETTER been turned into an English song of praise by our talented musician. Some of us are pondering “We aspire to be a caring church that empowers people for potential vocations which we heard from God as we were with you. The Dioceses are working on ABUNDANT LIFE” Youth from Iowa and Brechin rendering a song during the 2014 annual youth confer- ence at St Michaels Chapel. Reflection from The Dean new projects and plans to deepen our work together and we are entrusting the future to God and to your I greet you in the name of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. I write hands and hearts together now that the introductions have been made. Thank you, dear people of Swazi- to you just before we begin Lent and in one of the past important land. You are God‘s instruments of encouragement and spiritual renewal for us all. days we remembered a host of important Saints. -

Click Here to Download Newsletter

Bishop of Maidstone’s Newsletter Pre-Easter 2021 In this edition: • Pastoral Letter from Bishop Rod • An Update on the Bishop’s Six Priorities for this Quinquennium • Regional Meetings in 2021 • An Introduction from Dick Farr • Online Resources for Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Season • Meeting with the Archbishop of York (24th May) • Vacancies • Requests for the Bishop’s Diary • Bishop’s Coffee Breaks • Bishop’s Staff Team & Contact Details • Prayer Requests • List of Resolution Parishes Pastoral Letter from Bishop Rod Dear Fellow Ministers ‘On him we have set our hope’ (2 Corinthians 1:10) I’ve often wondered how Paul kept going, given the circumstances he faced. Take 2 Timothy for example. The whole letter is set against a very discouraging background of imprisonment and widespread apostasy. Or take 2 Corinthians. In chapter 1, Paul talks of being ‘so utterly burdened beyond our strength that we despaired of life itself’ (verse 8). But as he looks back on a dreadful time, he concludes that ‘this was to make us rely not on ourselves but on God who raises the dead. He delivered us from such a deadly a peril, and he will deliver us. On him we have set our hope that he will deliver us again’ (vv 9-10). As we come towards the end of the third lockdown, I’m very conscious of the unremitting pressure on church leadership teams to keep ministering online, while individual members have to balance this with care for their families, and all in the relative isolation of lockdown. On top of this comes the need to plan for a changed future when there are still so many unknowns. -

For PSYCHICAL STUDIES

The CHURCHES’ for PSYCHICAL and SPIRITUAL STUDIES QUARTERLY REVIEW V No. 57 ■ September 1968 Contents include: W? Transplant Surgery .. 12-13 Rev. Dr. K. G. Cuming, Major Tudor Pole, Mr. Cyril Smith C.F.P.S.S. Recommendations to Lambeth Conference .. 9 Book Reviews .. 14-16 Readers’ Forum 17-18 C.F.P.S.S. Pilgrimages .. 3 Healing News .. 6 ONE SHILLING & SIXPENCE (U.S.A, and CANADA—25 Cents) The Churches’ Fellowship for Psychical and Spiritual Studies Headquarters: 5/6 Denison House, Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, S.W.l (01-834 4329) Founder—Lt.-Col. Reginald M. Lester, F.J.I. President—The Worshipful Chancellor The Rev. E. Garth Moore, M.A., J.P. Vice-President—The Bishop of Southwark Chairman—Lt.-Col. Reginald M. Lester, F.J.I. Vice-Chairman—The Rev. Canon J. D. Pearce-Higgins, M.A.. Hon. C.F. General and Organizing Secretary—Percy E. Corbett, Esq. Hon. General Secretary—Rev. Dr. K. G. Cuming, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. Hon. Secretary Youth Section—Miss O. Robertson Patrons: Bishop of London Bishop of Southwell Rev. Dr. Leslie Weatherhead Bishop of Birmingham Bishop of Wakefield Canon The Ven. A. P. Shepherd Bishop of Bristol Bishop of Worcester Rev. Lord Soper Bishop of Carlisle Bishop of Pittsburgh, U.S.A. Rev. Dr. Leslie Newman Bishop of Chester Rt. Rev. Dr. G. A. Chase E. J. Allsop, J.P. Bishop of Chichester Very Rev. Dr. W. R. Matthews George H. R. Rogers, C.B.E., M.P. Bishop of Colchester Ven. E. F. Carpenter Dr. -

Prayer Diary Pray for Cleeve Prior & the Littletons and for Our Open the Book Teams Who Ordinarily Bring the Bible to Life in Our Village Schools

Sunday 28 FEBRUARY Lent 2 Living in Love and Faith Pray that people throughout Recently the Church of England launched ‘Living our diocese will feel able in Love and Faith’ with a set of free resources to engage with this process about identity, sexuality, relationships and with love and compassion, marriage, drawing together information from praying particularly for those the Bible, theology, science and history with who might find it difficult for powerful real-life stories. whatever reason. The Church is home to a great diversity of people who have a variety of opinions on these topics. The resources seek to engage with these differences and include a Pershore & Evesham Deanery 480-page book, a series of films and podcasts and a course amongst other things. Area Dean: Sarah Dangerfield As a diocese, we will be looking at Living in Love and Faith at Diocesan Synod next Saturday and parishes and deaneries are encouraged to reflect on how they Anglican Church in Central America: might also engage. Bishop Julio Murray Thompson Canterbury: Bishop John said: “As bishops, we recognise that there have been deep and painful Archbishop Justin Welby with divisions within the Church over questions of identity, sexuality, relationships and Bishops Rose Hudson-Wilkin (Dover), marriage, stretching back over many years, and that a new approach is now Jonathan Goodall (Ebbsfleet), needed. Those divisions are rooted in sincerely held beliefs about God’s will, but go Rod Thomas (Maidstone), to the heart of people’s lives and loves. I hope and pray that people will feel able to Norman Banks (Richborough) engage with this process with love, grace, kindness and compassion.” Down and Dromore (Ireland): Bishop David McClay The free online resources can be found at churchofengland.org/LLF. -

Welcome to Praxis Praxis South Events for 2018: He Church Exists to Worship God

Welcome to Praxis Praxis South Events for 2018: he church exists to worship God. Worship is the only activity of the Church Getting ready for the Spirit! Twhich will last into eternity. Speaker: the Rev’d Aidan Platten Bless your enemies; pray for those Worship enriches and transforms our lives. In Christ we An occasion to appreciate some of the last liturgical are drawn closer to God in the here and now. thoughts of the late Michael Perham. who persecute you: Worship to This shapes our beliefs, our actions and our way of life. God transforms us as individuals, congregations Sacraments in the Community mend and reconcile. and communities. Speaker: The Very Rev’d Andrew Nunn, Dean of Worship provides a vital context for mission, teaching Southwark and pastoral care. Good worship and liturgy inspires A day exploring liturgy in a home setting e.g. confession, and attracts, informs and delights. The worship of God last rites, home communion can give hope and comfort in times of joy and of sorrow. Despite this significance, we are often under-resourced Please visit our updated website for worship. Praxis seeks to address this. We want to www.praxisworship.org.uk encourage and equip people, lay and ordained, to create, to keep up-to-date with all Praxis events, and follow the lead and participate in acts of worship which enable links for Praxis South. transformation to happen in individuals and communities. What does Praxis do to offer help? Praxis offers the following: � training days and events around the country (with reduced fees for members and no charge for ordinands or Readers-in-training, or others in recognised training for ministry) � key speakers and ideas for diocesan CME/CMD Wednesday 1 November 2017 programmes, and resources for training colleges/courses/ 10.30 a.m. -

Bread of Life: Bishops' Teaching Series

Bread of Life: Bishops’ teaching series 3 - Remembering: anamnesis – Bishop Rod Thomas Welcome to the third of our ‘Bread of Life’ series. Today we’re going to explore the way in which Holy Communion helps us to remember Christ’s death. Memories are powerful things, aren't they? They can on the one hand inspire us to live better and on the other they can restart old animosities. They can give pleasure or pain. What you remember plays an important part in your outlook on life. As Shakespeare put it ‘purpose is a slave to memory’. It's no surprise therefore that the Bible urges us time and again to remember certain things - because as we remember we remind ourselves of the character of God, of his actions in history, of the promises he has made, and of our place in his plans – our purpose. In this session of our ‘Bread of Life’ series we're going to look at the command to ‘remember’ that our Lord Jesus gave at the Last Supper. In 1 Corinthians 11, the Apostle Paul narrates the command in this way: “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it , and said,“ this is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also he took the Cup, after supper, saying “this Cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” for as often as you eat this bread and drink this Cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.” These words are repeated in the prayer of consecration at our Holy Communion services. -

Corpus Christi College the Pelican Record

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LII December 2016 i The Pelican Record Editor: Mark Whittow Design and Printing: Lynx DPM Published by Corpus Christi College, Oxford 2016 Website: http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] The editor would like to thank Rachel Pearson, Julian Reid, Joanna Snelling, Sara Watson and David Wilson. Front cover: Detail of the restored woodwork in the College Chapel. Back cover: The Chapel after the restoration work. Both photographs: Nicholas Read ii The Pelican Record CONTENTS President’s Report .................................................................................... 3 Carol Service 2015 Judith Maltby.................................................................................................... 12 Claymond’s Dole Mark Whittow .................................................................................................. 16 The Hallifax Bowl Richard Foster .................................................................................................. 20 Poisoning, Cannibalism and Victorian England in the Arctic: The Discovery of HMS Erebus Cheryl Randall ................................................................................................. 25 An MCR/SCR Seminar: “An Uneasy Partnership?: Science and Law” Liz Fisher .......................................................................................................... 32 Rubbage in the Garden David Leake ..................................................................................................... -

ND Sept 2019.Pdf

usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] parish directory www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm. St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Weekdays - Low Mass: Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - http://stpetersfolk.church e-mail :[email protected] tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 parishes.org.uk 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . GRIMSBY St Augustine , Legsby Avenue Lovely Grade II Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term Church by Sir Charles Nicholson. A Forward in Faith Parish under BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ time) On 5th Sunday a Group Mass takes place in one of the 6 Bishop of Richborough . Sunday: Parish Mass 9.30am, Solemn Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at churches in the Benefice.