This Is the Best I Can Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

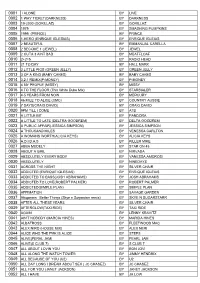

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Grinspoon Album Download

Grinspoon album download click here to download FreeDownloadMp3 - Grinspoon free mp3 (wav) for download! Newest Grinspoon ringtones. Collection of Grinspoon albums in mp3 archive. List of all Grinspoon albums including EPs and some singles - a discography of Grinspoon CDs and Grinspoon records. List includes Grinspoon album cover artwork in m. ARTIST: Grinspoon; ALBUM / TITLE: Discography; RELEASE YEAR / DATE: ; COUNTRY: Australia; STYLE: Alt Rock, Hard Rock, Post-Grunge; DURATION: ; FILE FORMAT: MP3; QUALITY: kbps; Site: www.doorway.ru; RATING: 10 / 4; VOTE: 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; DOWNLOAD: DOWNLOAD. Complete your Grinspoon record collection. Discover Grinspoon's full discography. Shop new and used Vinyl and CDs. Listen to Grinspoon | SoundCloud is an audio platform that lets you listen to what you love and share the sounds you create.. Sydney. Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Grinspoon on your desktop or mobile device. Albums from this user. View all · Grinspoon · New Detention. Album · Grinspoon · Album Collection. Album · Grinspoon · Guide To Better Living. Album · October ; "St. Louis" – "Easyfever" Easybeats Tribute Album, October A video was also recorded and released as a single off the album. "Champion ( version)" – download from official site, ; "When You Were Mine" (Prince cover) – performed on Triple Video albums: 2. Grinspoon is an Australian rock band from Lismore, New South Wales formed in and fronted by Phil Jamieson on vocals and guitar with Pat Davern on guitar, Joe Hansen on bass guitar and Kristian Hopes on drums. Also in , they won the Triple J-sponsored Unearthed competition for Lismore, with their. Listen to songs and albums by Grinspoon, including "Champion," "Don't Change," "Snap Your Fingers, Snap Your Neck," and many more. -

Mcgraw-Hill's Essential English Irregular Verbs (Mcgraw-Hill ESL

McGRAW-HILL’S ESSENTIAL English Irregular Verbs This page intentionally left blank McGRAW-HILL’S ESSENTIAL English Irregular Verbs MARK LESTER, PH.D. • DANIEL FRANKLIN • TERRY YOKOTA New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2010 by Mark Lester, Daniel Franklin, and Terry Yokota. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-160287-7 MHID: 0-07-160287-9 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-160286-0, MHID: 0-07-160286-0. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occur- rence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefi t of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please e-mail us at [email protected]. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGrawHill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. -

Full Song List by Song A

CODE SONG ARTIST TIME CAB1 123 Len Barry ‐ 2:30 CAB2 1234 Feist ‐ 3:02 CAB3 1973 JAMES BLUNT ‐ 3:56 CAB4 1985 Bowling for Soup ‐ 3:14 CAB5 1999 Prince 3:39 CAB6 (FAR FROM) HOME TIGA ‐ 2:51 CAB4682 (All Of A Sudden) My Hearts Sings Paul Anka 3:01 CAB7 (And She Said) Take Me Now Justin Timberlake ft Janet Jac ‐ 5:31 CAB8 (Can't Get My) Head Around You The Offspring ‐ 2:14 CAB9 (Don't) Give Hate A Dance Jamiroquai ‐ 3:48 CAB10 (Everybody) Get Up (Rogers Zap Roger ‐ 6:03 CAB4676 (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Sam Cooke 3:13 CAB4677 (If You Cry) True Love, True Love The Drifters 2:16 CAB4809 (It's Been A Long Time) Pretty Baby Gino & Gina 2:01 CAB4510 (The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance Gene Pitney 2:27 CAB4766 (There'll Be) Peace In The Valley (For Me) Elvis Presley 3:21 CAB11 (There's) Always Something The Sandie Shaw ‐ 2:42 CAB12 (They Long to Be) Close to You The Carpenters ‐ 4:31 CAB13 (When You Gonna) Give It Up To Various ‐ 4:03 CAB4358 (You've Got) The Magic Touch The Platters 2:26 CAB14 1 Thing Amerie Feat Eve ‐ 3:57 CAB15 1,2 Step Ciara feat Missy Elliott ‐ 3:17 CAB16 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters ‐ 3:06 CAB17 13, Storia D'oggi Al Bano 4:14 CAB18 15 Minut Projekt 15 Minut Projekt 6:55 CAB4418 16 Candles The Crests 2:51 CAB19 1983 (Eric Prydz Remix) Dirty South ‐ 3:15 CAB20 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue ‐ 2:52 CAB21 2 TIMES ANN LEE ‐ 3:46 CAB22 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc ‐ 3:46 CAB23 20 Miles Ray Brown And The Whispers ‐ 2:18 CAB24 22 STEPS DAMIEN LEITH ‐ 3:32 CAB25 24 MILA BACI LITTLE TON 2:48 CAB26 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 3:18 CAB27 3,2,1 Remix P‐MONEY FEAT. -

SL Xpress & Melody Library2

Artist Title 112 Dance With Me 112 Na Na Na Na 100% Feat. Jennifer John Just Can't Wait (Saturday) 10CC I'm Not In Love 1200 Techniques Fork In The Road (Clean Radio Edit) 1200 Techniques Karma 28 Days Like I Do 28 Days Rip It Up 28 Days & Apollo 440 Say What 2Pac California Love 2Pac Changes 2Pac Thugz Mansion 2Pac Feat. Ashanti & T.I. Pac's Life (Explicit Version) 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 The Hard Way It's On 30 Seconds To Mars A Beautiful Lie 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday (Radio Edit) 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill (Bury Me) Radio Edit 30h!3 Don't Trust Me 3-11 Porter Surround Me With Your Love 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Wings Penelope 50 Cent 21 Questions (G Version) 50 Cent Candy Shop (Edited) 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent Hustlers Ambition (Edit) 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club (Clean Version) 50 Cent Just A Li'l Bit (Clean) 50 Cent P.I.M.P 50 Cent Questions 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent Window Shopper (Edited Version) 50 Cent Eminem & Dr Dre Crack A Bottle (Clean Edit) 50 Cent Feat. Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology (Album Version) (Explicit) 50 Cent Feat. Mobb Deep Outta Control (Remix - Radio Edit) 67 Special Lady Gin 67 Special Shot At The Sun 78 From Home Brand New Day A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Friend From Rio Para Lennon & McArtney A New Funky Generation Lubumba 98 A New Funky Generation The Messenger A Perfect Circle Judith A Perfect Circle Weak And Powerless A Tribe Called Quest Bonita Applebum A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It? A Tribe Called Quest Check The Rhime A Year To Remember Tastefully Tricky A.R. -

Trouble Songs

trouble songs Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-proft press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afoat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t fnd a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la open-access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) trouble songs. Copyright © 2018 by Jef T. Johnson. Tis work carries a Cre- ative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and trans- formation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2018 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-44-8 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-45-5 (ePDF) lccn: 2018930421 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book design: Vincent W.J. -

Mcgraw-Hill's Essential English Irregular Verbs

McGRAW-HILL’S ESSENTIAL English Irregular Verbs This page intentionally left blank McGRAW-HILL’S ESSENTIAL English Irregular Verbs MARK LESTER, PH.D. • DANIEL FRANKLIN • TERRY YOKOTA New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2010 by Mark Lester, Daniel Franklin, and Terry Yokota. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-160287-7 MHID: 0-07-160287-9 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-160286-0, MHID: 0-07-160286-0. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occur- rence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefi t of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please e-mail us at [email protected]. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGrawHill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. -

Songwriting for Dummies, Second Edition

spine=.7680” Get More and Do More at Dummies.com® 2nd Edition Start with FREE Cheat Sheets Cheat Sheets include • Checklists • Charts • Common Instructions • And Other Good Stuff! Mobile Apps To access the Cheat Sheet created specifically for this book, go to www.dummies.com/cheatsheet/songwriting Get Smart at Dummies.com Dummies.com makes your life easier with 1,000s of answers on everything from removing wallpaper to using the latest version of Windows. Check out our • Videos • Illustrated Articles There’s a Dummies App for This and That • Step-by-Step Instructions With more than 200 million books in print and over 1,600 unique Plus, each month you can win valuable prizes by entering titles, Dummies is a global leader in how-to information. Now our Dummies.com sweepstakes. * you can get the same great Dummies information in an App. With Want a weekly dose of Dummies? Sign up for Newsletters on topics such as Wine, Spanish, Digital Photography, Certification, • Digital Photography and more, you’ll have instant access to the topics you need to • Microsoft Windows & Office know in a format you can trust. • Personal Finance & Investing • Health & Wellness To get information on all our Dummies apps, visit the following: • Computing, iPods & Cell Phones www.Dummies.com/go/mobile from your computer. • eBay • Internet www.Dummies.com/go/iphone/apps from your phone. • Food, Home & Garden Find out “HOW” at Dummies.com *Sweepstakes not currently available in all countries; visit Dummies.com for official rules. Songwriting FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by Jim Peterik, Dave Austin, Cathy Lynn Foreword by Kara DioGuardi 01_615140-ffirs.indd i 6/25/10 7:47 PM Songwriting For Dummies®, 2nd Edition Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. -

Song List by Song

Song List by Song Song Name Artist (ABSOLUTELY) STORY OF A GIRL NINE DAYS (DON’T) GIVE HATE A CHANCE JAMIROQUAI (HONEY PLEASER/BASS TONE) 33HZ (SHE’S GOT) SKILLZ ALL‐4‐ONE 1 2 3 MARIA RED HARDIN 1 4 U SUPERHEIST 1, 2 STEP CIARA FEAT MISSY ELLIOTT 1, 2, 3, 4 GLORIA ESTEFAN AND MIAMI SOUND MACHINE 10,000 PROMISES BACKSTREET BOYS 100 MILES AND RUNNING N.W.A. 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING 100% PURE LOVE CRYSTAL WATERS 1234 REMIX COOLIO 13 STEPS TO NOWHERE PANTERA 138 TREK DJ ZINC 18 TIL I DIE BRYAN ADAMS 19 SOMETHIN' Page 1 of 525 Song List by Song Song Name Artist MARK WILLS 19'2000 GORILLAZ 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 1999 PRINCE 1ST OF THA MONTH BONE THUGS N HARMONY 2 LEGIT 2 QUIT MC HAMMER 2 OUT OF 3 AINT BAD MEATLOAF 2 TIMES ANN LEE 20 GOOD REASONS THIRSTY MERC 21 QUESTIONS [FEAT NATE DOGG] 50 CENT 21 SECONDS SO SOLID CREW 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID MAN KING CRIMSON 22 STEPS DAMIEN LEITH 24 INSANE CLOWN POSSE 24 7 KEVON EDMONDS 24 HOURS ORGINAL MIX AGENT SUMO Page 2 of 525 Song List by Song Song Name Artist 2468 MOTORWAY TOM ROBINSON BAND 25 MILES 2001 3 AMIGOS 25 OR 6 TO 4 CHICAGO 2ND HAND PITCHSHIFTER 2S COMPANY CHARLTON HILL 3 IS FAMILY DANA DAWSON 3 LIBRAS A PERFECT CIRCLE 3 LITTLE PIGS GREEN JELLO 3,2,1 REMIX P MONEY 3:00 AM MATCHBOX 20 37MM AFI 3AM MATCHBOX 20 3AM ETERNAL KLF 4 EVER THE VERONICA’S 4 IN THE MORNING GWEN STEFANI 4 MY PEOPLE MISSY ELLIOTTT 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS Page 3 of 525 Song List by Song Song Name Artist BOYZ II MEN 40 MILES OF BAD ROAD TWANGS 48 CRASH SUZY QUATRO 4EVER VERONICAS 5 YEARS FROM NOW MERCURY 4 51ST STATE, THE PRE SHRUNK 5678 STEPS 5IVE MEGAMIX 5IVE 5TH SYMPHONY 1ST MOVEMENT BEETHOVEN 60 MILES AN HOUR NEW ORDER 604 ANTHRAX 68 GUNS ALARM 7 PRINCE 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 7 YEARS AND 50 DAYS CASCADA 70'S LOVE GROOVE JANET JACKSON 72 HOUR DAZE TAXIRIDE Page 4 of 525 Song List by Song Song Name Artist 7654321 SURPRISE 77% HERD 7TH SYMPHONY BEETHOVEN 8 MILES AND RUNNIN’ FREEWAY FEAT. -

Grinspoon Hold on Me Mp3 Download

Grinspoon hold on me mp3 download Download Play now Download Hold On Me — Thrills, Kills and Sunday Pills — Grinspoon Stunningly! 3 best mp3 from Thrills, Kills and Sunday Pills. Buy Hold On Me: Read Digital Music Reviews - Free download Grinspoon Hold On Me Mp3. We have about 14 matching results to play and download. If the results do not contain the songs you were looking. grinspoon-lyrics/3 duration: - size: MB. download. listen. embed. Grinspoon - Lost Control mp3. Mix - Grinspoon - Hold On MeYouTube · Grinspoon - Black Tattoo - Duration: yourgrinspoon 24, Grinspoon - Chemical 3, Mb. Grinspoon - Bleed You 3, Mb. Grinspoon - Hold On 3, Mb. Grinspoon - Better Off. Free Download Grinspoon Repeat mp3, Grinspoon - Repeat,Grinspoon - Repeat, song download, music, mp3adio, audio, lyrics. Grinspoon - Hold On Me mp3. Download free: Ready 1 Grinspoon 3. Please enter the characters you see in GRINSPOON - No Reason Six to Midnight Tour Enmore 3. "Hold on Me" is the third single released by Grinspoon from their fourth studio album Thrills, Kills & Sunday Pills. It was released on 21 February on the Released: 21 February Download Summer Grinspoon mp3 songs in High Quality kbps format, Play Summer Grinspoon Music Grinspoon - Hold On Me (MTV Music Awards ). Download Run Grinspoon mp3 songs in High Quality kbps format, Play Run Grinspoon Music track Grinspoon - Hold On Me (MTV Music Awards ). Lyrics to 'Hold On Me' by Grinspoon. 1, 2, 3, 4 how come you never want to dance with me anymore? lying cold Can You Guess The Song By The Emojis? Download She S Leaving Tuesday Grinspoon mp3 songs in High Quality kbps format, Play She S Leaving Making of Grinspoon "Hold On Me" Part 1.