Ocassional Paper 21 Font Size Increase.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

57Bc48824ee9e-1310472-Sample

Notion Press Old No. 38, New No. 6 McNichols Road, Chetpet Chennai - 600 031 First Published by Notion Press 2016 Copyright © Madanjit Singh Ahluwalia 2016 All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-945497-75-9 This book has been published with all efforts taken to make the material error-free after the consent of the author. However, the author and the publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. No part of this book may be used, reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Cover image: Indian Navy Contents Acknowledgements xiii Introduction xv 1. INS Khukri 1 2. Comments 25 3. Rebellion in East Pakistan 26 4. Pakistani Naval Submarine Ghazi 40 5. The Landings at Cox’s Bazaar 55 6. Kissa Enterprise Ka 65 7. Task Force Alfa 75 8. The Missile Boat Attacks on Karachi 78 9. Pakistan in 1971 110 10. Major Ian Cardozo, SM, 4/5 Gurkha Rifles, Reports for Duty 120 Conclusion 141 Those Who Made the Supreme Sacrifice 143 INS Khukri I reported on board Indian Naval Ship Khukri at Mumbai on 16 May, 1971. She was made fast to the caisson gate of the Cruiser Graving dock, inside the naval dockyard. A caisson gate is an awkward spot to berth a frigate. She had been put there since there was a shortage of alongside berths. -

Capability Based Force Structures for India 2015-2025

CAPABILITY BASED FORCE STRUCTURES FOR INDIA 2015-2025 By Maj Gen G D Bakshi SM, VSM (retd) Force Structuring can be done in two ways – Threat based or Capability based. Traditionally, Indian Force structures have generally been premised upon a threat-based analysis in the post-independence period. Indian Military history, howver, can be studied in terms of the three local Revolutions in Military Affairs (RMAs) that ushered in very major changes in the socio-political realm. In fact South Asia has largely been a civilisational and not a political entity. There were only three episodes of unification in its 5000 year long history. The three unifications of South Asia were in fact effected by local RMAs that replaced the attrition mindset with a manoeuvrist orientation. These three RMAs ushered in significant changes in the Indian political and economic spheres. The three RMAs were:- - The Elephant Based RMA of the Mauryans. This unified India in the wake of Alexander’s invasion. Kautilya in fact first unified India from Afghanistan and Baluchistan frontier regions down to Karnataka. He achieved this by using War elephants in the mass to generate “Shock and Awe” and usher in unprecedented rates of mobility in all types of terrain. He was a master of Information warfare. The Kautilyan Paradigm provides the essence of an Indian Strategic culture that has tended to persist over the millenniums and reasserted itself whenever India became a unified entity. - The Cavalry, Field Artillery and Musket based RMA of the Mughals. This unified India under the Mughal Empire by an intelligent combination of Horsed Archers, Field Artillery and Muskets. -

Lt Gen Hanut Memorial

1 I N T R O D U C T I O N It is indeed a great privilege to have been asked to deliver the inaugural late Lt Gen Hanut Singh Memorial Lecture, in honour of this iconic Cavalry General and battle field leader, who remains a role model for many across the Indian Armed Forces. • I thank Lt Gen Vinod Bhatia, Director, Centre of Joint Warfare Studies and also Lt Gen Ashok Shivane, DGMF, for having given me this opportunity. • The subject I am covering today is vital to all of us assembled here: “Military Leadership in the 21st Century”. But it is even more vital to the Nation, for the Indian Armed Forces are the ultimate guarantors of our Nation’s Security and well being, and how this instrument of ‘Last Resort’ performs will be largely determined by the leadership that steers this organization in peace and leads it in war. • Seated here today amongst the audience are some of the iconic leaders of yesteryears, some of whom have rubbed shoulders with the legendary Gen Hanut. The presence of our Hon’ble Raksha Mantri is greatly motivating for all of us. Having interacted with him on a number of occasions, I can say with conviction that the operational preparedness and well being of the Armed Forces are in very steady and capable hands and very close to his heart. Thank you, Sir, for being here with us today. 2 • Before starting let me just recount my meeting with Gen Hanut in 2012 at Dehradun, when I was Southern Army Commander. -

Param Vir Chakra Vijeta • Maha Vir Chakra Vijeta

PPT Competition Heros of 1971 War • Param Vir Chakra Vijeta • Maha Vir Chakra Vijeta Lt. Gen. J.F.R. Jacob PPT Competition 1 Lance Naik Albert Ekka 2 Flying Officer Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon 3 Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal 4 Major Hoshiar Singh 5 Lt Col Jaivir Singh 6 AVM Vidya Bhushan Vasisht 7 Gp Capt Allan Albert D’Costa 8 Sub Maj Bir Bahadur Pun Kasargod Patnashetti Gopal 9 Cmde Rao 10 Gen Arun Shridhar Vaidya 11 Cmde Babru Bahan Yadav PPT Competition 11 Cmde Babru Bahan Yadav 12 Capt Devinder Singh Ahlawat Krishnaswamy Gowri 13 Lt Gen Shankar 14 Brig Kuldip Singh Chandpuri 15 Brig Narinder Singh Sandhu 16 Wg Cdr Padmanabha Gautam 17 Air Mrshl Ravinder Nath Bhardwaj 18 Lt Col Sawai Bhawani Singh 19 Lt Gen Joginder Singh Gharaya 20 Brig Kailash Prasad Pande 21 Brig Mohindar Lal Whig PPT Competition 21 Brig Mohindar Lal Whig 22 Sep Pandurang Salunkhe 23 AVM Chandan Singh 24 Maj Gen Chittoor Venugopal 25 Lt Gen Joginder Singh Bakshi 26 Sub Maj Mohinder Singh 27 Maj Chewang Rinchen 28 P/O Chiman Singh 29 Cdr Joseph Pius Alfred Noronha 30 Brig Udai Singh 31 Capt Mahendra Nath Mulla 32 Nt Sugan Singh PPT Competition 31 Capt Mahendra Nath Mulla 32 Nt Sugan Singh 33 Brig Rattan Nath Sharma 34 Maj Gen Harish Chandra Pathak 35 Maj Kulwant Singh Pannu 36 Brig Sukhjit Singh 37 Maj Vijay Rattan Choudhry 38 L/Nt Drig Pal Singh 39 Capt Pradip Kumar Gour 40 Brig Amarjit Singh Bal 41 Sub Maj Thomas Phillopose 42 Lt Col Ved Prakash Ghai PPT Competition 41 Sub Maj Thomas Phillopose 42 Lt Col Ved Prakash Ghai 43 Lt Gen Hanut Singh 44 Lt Gen Raj Mohan Vohra Shankar Rao Shankhapan 45 Capt Walkar 46 AVM Cecil Vivian Parker. -

GK Digest 2015 This Was Part of PM Modi’S Visit to Three Indian Ocean Island Countries

www.BankExamsToday.com www.BankExamsToday.com www.BankExamsToday.com GKBy Ramandeep Singh Digest 2015 my pc [Pick the date] www.BankExamsToday.com GK DigestIndex 2015 List of Prime Minister’s Foreign visits 2-5 MoUs signed between India and Korea 5-14 List of Countries - Their Capital, Currency and Official Language 14-20 Popular Governmentwww.BankExamsToday.com Welfare Schemes 20-21 Awards and Honours in India – 2014 22 Awards and Honours in India 2015 23-30 Appointments 30-40 List of Committees in India 2015 40 International Summits in 2015 List 41-43 People in News During August 2015 43-45 Deaths 45-51 International Military Training Exercises 51-52 List of Cabinet Minister as on 30.11.2014 53-54 Union Budget 2015-16 54-58 Ministers and their constituencies 58-59 Important Indian Organizations and their Heads 59-60 Mergers and Acquisitions - Explained in Simple Language 60-62 List of Latest schemes and apps launched by banks 2015 63 Important Parliamentary Acts related to Banking sector in India 63-65 List of important days for banking and insurance exams 65-66 List of important days, useful for general awareness Section of banking exams 66-68 Important days to remember for August, September and October 68-69 Indian States - Capital - Chief Minister (CM) - Governor 69-72 List of important International Organizations with their headquarters, foundation years, heads and purpose 72-75 Wilf Life Sanctuaries in India 75-81 Indian Cities on the Bank of Important Rivers 82-83 List of national parks of India 83-88 Important Airports 89 IMPORTANT TEMPLES OF INDIA 90-97 LIST OF IMPORTANT CUPS AND TROPHIES – SPORTS 98-99 UNESCO HERITAGE SITES 99-127 Must Know Articles of Indian Constitution 128-132 Important Fairs 133-134 World Major Space Centers 134 www.BankExamsToday.com Page 2 www.BankExamsToday.com List of PrimeGK Minister’sDigest 2015 Foreign visits State Visit to Bhutan (June 15-16, 2014): At the invitation of Shri Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the King of Bhutan, Shri Narendra Modi paid a State Visit to Bhutan from 15-16 June 2014. -

President's Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL : 2017 1. Gentlemen, it gives me great pleasure to welcome you to the second meeting of the present Council. The USI is a unique, autonomous Institution with unequalled expertise in the field of National Security and matters pertaining to the Defence Services. It has built an outstanding reputation over the last 147 years. It is my privilege to present the report of the Institution for the year 2017. A copy of the report has been placed on the table and will be included in the minutes of the meeting. MEMBERSHIP 2. The Institution began with a membership of 215 members and was 3500 when it moved to its present premises in 1996. Today we have 14,321 Members. It is heartening to report that during the current year 137 new Life Members, 43 Associate Members, 107 Ordinary Members and 1217 Course Members were enrolled. This continuous growth exemplifies the support and trust the Institution enjoys. FINANCES 3. The Institution does not get any grant / aid from the Ministry of Defence or the Services. It continues to carry out all its activities from the resources generated within. Since the USI Centres {Center for Strategic Studies and Simulation (CS3) and Center for Armed Forces Historical Research (CAFHR)} are not able to meet their annual expenditure, they are allocated resources from the Corpus Fund. Further, our building and equipment being more than two decades old, now require greater allocation of funds for their renovation and upkeep. 4. The Audit Report and Balance Sheet for 2016-17, Revised Estimates for 2017-18 and Budget Estimates for 2018-19 are already with you. -

“Even God Lends a Hand to Honest Boldness – Meanander ''

“Even God Lends a Hand to Honest Boldness – Meanander ’’ Brigadier Rattan Kaul 4 / 5 G R { F F } {Brigadier Rattan Kaul was commissioned in 4/5 GR {FF} and was Rifle Company Commander during 1971 Operations. He was seriously injured in the Battle of Sylhet} History in The Making Some Respite or History in the Making. Gazipur Tea State near Kalaura of Sylhet District of then East Pakistan, defended by a company plus of 22 Baluch, had been annihilated on the night of 4/5 December 1971. A tough nut to crack, the resistance was fierce, for Pakistani's knew that after the failure of attack by 6 Rajput, a day earlier, they were in for another one very soon with more vigour and force. After the assault 15 dead bodies of the enemy had been counted and at least 40 of their wounded soldiers, including their company commander, were reported to have been carried away. We too suffered heavily; Major Shyam Kelkar, our Second-in-Command and 10 other ranks had made the supreme sacrifice. Four Officers; Major‘s Yashwant Rawat, Virender Rawat {Both Company Commander‘s}, two young officers, two JCO‘s and 57 other ranks were wounded. With attack on its Gazipur position, 22 Baluch was completely disorganised; lost communication with its sub units and left for Sylhet without giving any orders; to meet us again at Sylhet, two days later. Pakistani‘s vacated Kalaura, which was occupied by the battalion by mid-day 5 December. With Kalaura, key to the defences in this sector, Juri secured {59 Mountain Brigade}, road to Fenchuganj / Maulvi Bazar was open to own troops. -

16-17 Ministers Likely to Be Sworn in with Nitish

VVOLOL NNO.O. XXIIII IISSUESSUE NNO.O. 7788 PPAGES.AGES. 88+8+8 ` //-- 4 EENGLISHNGLISH DDAILYAILY THE16 MONDAY, NOVEMBER, SOUTH 2020 PUBLISHED FROM: HYDERABAD, CHENNAI INDIA & BANGALORE EDITOR INTIMES CHIEF: BUCHI BABU VUPPALA www.thesouthindiatimes.comw /facebook/thesouthindiatimes.yahoo.in / thesouthindiatimes.yahoo.in /@thesouthindiatimes PAGE-3 Kejriwal performs Diwali puja After slamming central probe at Akshardham bodies, Kerala CPI-M attacks CAG PAGE-4 SHORT TAKES UP girl child’s 16-17 Ministers likely to be sworn in with Nitish body found with Patna, Nov 15 (UNI) invited by Governor Ph- from the Sahani’s VIP and Defence Minister Rajnath ters to take oath in tomor- Around 16 to 17 minis- agu Chauhan to form the Jitan Ram Manjhi’s Hin- Singh, who was present in row’s (Monday) swearing organs missing ters are expected to be government, said that the dustani Awam Morcha- the meetings at the CM’s in ceremony.” According sworn-in along with Chief list of ministers will be de- Secular. “We will finalise residence as well as at the to sources, there will be Kanpur, Nov 15 (UNI) In Minister-designate Nitish cided by late Sunday eve- the names of ministers Raj Bhavan, not speaking seven ministers each from a ghastly incident, the Kumar in the oath-taking ning or early Monday. Ac- by late night or tomorrow on the issue. the Janata Dal-United butchered body of a six- ceremony on Monday, but cording to sources, there morning and submit it Vikassheel Insaan Party and the Bharatiya Janata year-old girl was found in it was not clear yet if Sushil will be seven ministers before the Governor,” he chief Mukesh Sahani, who Party, and one each from an Uttar Pradesh village in Kumar Modi will return each from the Janata Dal- said. -

Download in PDF Format

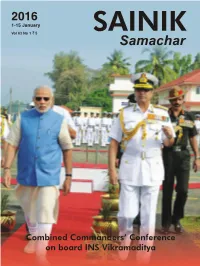

Happy New Year to all SainiksIn This andIssue Readers Since 1909 CombinedBIRTH ANNIVERSARY Commanders’ CELEBRATIONS Conference on board… 4 (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 63 q No 1 10 - 24 Pausha, 1937 (Saka) 1-15 January 2016 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief Dazzling Multi Activity Hasibur Rahman COAS Reviews the 8 14 Senior Editor Editor Passing Out Parade Display Ruby T Sharma Ehsan Khusro Coordination Business Manager Sekhar Babu Madduri Dharam Pal Goswami Our Correspondents DELHI: Dhananjay Mohanty; Capt DK Sharma; Manoj Tuli; Nampibou Marinmai; Wg Cdr Rochelle D’Silva; Col Rohan Anand; Ved Pal; ALLAHABAD: Gp Capt BB Pande; BENGALURU: Dr MS Patil; CHANDIGARH: Parvesh Sharma; CHENNAI: T Shanmugam; GANDHINAGAR: Wg Cdr Abhishek Matiman; GUWAHATI: Lt Col Suneet Newton; IMPHAL: Lt Col Ajay Kumar Sharma; JALANDHAR: Naresh Vijay Vig; JAMMU: Lt Col Manish Mehta; JODHPUR: Lt Col Manish Ojha; KOCHI: Cdr Sridhar E Warrier ; KOHIMA: Lt Col E Musavi; KOLKATA: Wg Cdr SS Birdi; 7 Greek Defence Minister… Dipannita Dhar; LUCKNOW: Ms Gargi Malik Sinha; MUMBAI: Cdr Rahul Sinha; 10 235th Anniversary and Reunion… 67th Anniversary of Narendra Vispute; NAGPUR: Wg Cdr Samir S Gangakhedkar; PALAM: Gp Capt SK 12 Training of Gentleman Cadets… Kargil… 18 Mehta; PUNE: Mahesh Iyengar; SECUNDERABAD: MA Khan Shakeel; SHILLONG: Gp Capt Amit Mahajan; SRINAGAR: Col NN Joshi; TEZPUR: Lt Col Sombith Ghosh; 20 Chief of the Air Staff Visits… THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Suresh Shreedharan; UDHAMPUR: Col SD Goswami; 24 A Tribute to Brave Yodhas of… VISAKHAPATNAM: Cdr CG Raju. -

President's Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL - 2016 (Established : 1870) UNITED SERVICE INSTITUTION OF INDIA PRESIDENT’S REPORT FOR 2016 1. Gentlemen, it gives me great pleasure to welcome you to the fourth meeting of the present Council. The USI is a unique, autonomous Institution with unequalled expertise in the field of National Security and matters pertaining to the Defence Services. It has built an outstanding reputation over the last 146 years. It is my privilege to present the report of the Institution for the year 2016. A copy of the report has been placed on the table and will be included in the minutes of the meeting. MEMBERSHIP 2. The Institution began with a membership of 215 members. When it moved to its present premises in 1996, the membership stood at about 3500 and today it is 14,111 Life, Ordinary, Associate and Course Members. It is heartening to report that during the current year 245 new Life Members were enrolled. This continuous growth exemplifies the support and trust the Institution enjoys. FINANCES 3. The Institution does not get any grant / aid from the Ministry of Defence or the Services. It continues to carry out all its activities from the resources generated within. Since the USI Centres {Center for Strategic Studies and Simulation (CS3) and Center for Armed Forces Historical Research (CAFHR)} are not able to meet their annual expenditure, they are allocated resources from the Corpus Fund. Further, our building and equipment being more than two decades old, now require greater allocation of funds for their renovation and upkeep. -

समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings

समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings दैिनक सामियक अिभज्ञता सेवा A Daily Current Awareness Service Vol. 45 No. 47 05 March 2020 रक्षा िवज्ञान पुतकालय Defence Science Library रक्षा वैज्ञािनक सूचना एवं प्रलेखन के द्र Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre मैटकॉफ हाऊस, िदली - 110 054 Metcalfe House, Delhi - 110 054 Thu, 05 March 2020 Gaganyaan: DRDO to provide special space food and emergency survival kit for ISRO’s manned mission ISRO is already working on a Humanoid prototype (with a female form)for the Gaganyaan missions, which is expected to be sent out on a mission next year to test it out before actually sending humans in space By Huma Siddiqui Special Space food, crew health monitoring and emergency survival kit is all going to be provided to the Indian Space Research Organisation’s Human Space Mission by Defence Research andand Development Organisation (DRDO). According to officials, “Both ISRO and DRDO have an MoU in place to provide all necessary support for the Human Space Mission which includes critical technologies like radiation measurement and protection, parachutes for the safesafe recovery ofof the crew module and fire suppression system.” Adding, “There is an agreement in place between the two agencies to provide technologies for human-centric systems and technologies specific to the Human Space Mission.” ISRO is already working on a Humanoid prototype (with a female form)for the Gaganyaan missions, which is expected to be sent out on a mission next year to test it out before actually sending humans in space.