Informanon to USERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Angeles Event Center

OV,\l'l.\l&Hf YI' t ITV ,iAN'YINot: C ITY OF LOS ANGELES ~1, .. '-• ...~ '-~~•111... u, ' "'""'" • 1: ) .w..111 :A,:tM:l<:t.c:A 11'1.1~ CAu-'<>MMA :O •Jto\"' .....:a n • '-l4JV•" "'Mli",O\ ... JJ> t••~••'~'' ,V,.. ►flt..AC• """"\M~,'- ' ,.,, Cff\l!'l'OUC:"~ t c;r;y " ,.. ..... N( ,"!0... Wli~ 1J•f.Jltt, : ,, Wl,,l~Yi(,11t!lt,V_. ... 1,t.... M \\I r :/11 11,-'( ,' __ I-':"... ~ 1«Jl't,. "'- l lltt• 111(..,_,.,,. vo1, , .......... IVN ;; ,, ,.. t ... n.~ v.. ~t"r. 01.:::oc,icao ):f-hL~ 1,1UC J 1ifN,,r.J.,MH u,,;.,.-..•~!J '., \(N ~~ ,:.......~hi ... ·~, 1fl,,\f\- 1.#ttl!H~ WJ~lltl l,Wtl .,.,. ::•"'"'"'"' 1.-.i... _ .-j,ui._ , -.....,. ~., ...,, ........,~ .. f\,11:t:,.•~ oJ • )it:11,.1.)« H~ Antooo R Volara,g0$,i! Mayor Ci1y ot l.os ~oles City Han, Room 300 Los Angele~. CA 90012 Attcnti<>n: Ms. Gaye Willams c.. ar M;rJ<)( Vllar'"9Q'x!' MAYOR'S EXECUTIVE DIRECTIVE NO. 22 DOWNTOWN EVENT carre:R PLANNING Th-e Executive Oirective V'3S issued dJe :O 3le- ~ifalnce of tt.~ Cofl\-ention and Event Center Project Jo, Los An9e.'es. The goal ls to n-.a,omiza the con,.-t>Jtion ol lh9 Fannor's F,eld pn,j~ lo U-.e economic ~rowth. CMC ife and tvabiliy ol Downtown Los Angel9s- The Execurvo Dtrw.-ve ~ up the coordrnle<I actions ol Uie Depar.menl$ of City f'lanning, Tr~ooo. f'\Jbic Works, Conventior. Cen,e, arid CulllJ'at Affo>h. The Cty Oepar.me.'l1S -ed together 10 M!Ue that thoughtful design, axh~eclure, :iro ptaruw,g aro efll)loyed in Ole review ol tile project. -

Individual Artist Fellowships C.O.L.A

INDIVIDUAL ARTIST FELLOWSHIPS C.O.L.A. 2013 C.O.L.A. 2013 INDIVIDUAL ARTIST FELLOWSHIPS Department of Cultural Affairs City of Los Angeles This catalog accompanies an exhibition and performance series sponsored by the City of Los CITY OF Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs featuring LOS ANGELES its C.O.L.A. 2013 Individual Artist Fellowship recipients in the visual and performing arts. 2013 INDIVIDUAL Exhibition: May 19 to July 7, 2013 ARTIST Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery FELLOWSHIPS Barnsdall Park Opening Reception: May 19, 2013, 2 to 5 p.m. Performances: June 28, 2013 Grand Performances 2 Antonio R. Villaraigosa LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL CULTURAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION Department of Cultural Affairs DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AffaiRS Mayor City of Los Angeles City of Los Angeles City of Los Angeles Ed P. Reyes, District 1 York Chang Paul Krekorian, District 2 President Olga Garay-English Aileen Adams Dennis P. Zine, District 3 The Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) generates and supports high-quality Executive Director Deputy Mayor Tom LaBonge, District 4 Josephine Ramirez arts and cultural experiences for Los Angeles’s 4 million residents and 40 million Strategic Partnerships Paul Koretz, District 5 Vice President Senior Staff Tony Cardenas, District 6 annual overnight and day visitors. DCA advances the social and economic impact of the arts and ensures access to diverse and enriching cultural activities through Richard Alarcon, District 7 Maria Bell Matthew Rudnick Bernard C. Parks, District 8 Annie Chu grant making, marketing, public art, community arts programming, arts education, Assistant General Manager Jan Perry, District 9 Charmaine Jefferson and building partnerships with artists and arts and cultural organizations in Herb J. -

April Studied at Kansas City Art Institute As a Graphic Design Major

April Greiman April studied at Kansas City Art Institute as a graphic design major. At the Art Institute, April began to learn about and explore Modernism. Some of her professors at the Kansas City Art Institute had studied at the Basel School of Design in Switzerland. Enthused by her professors, April decided to attend the Basel School of Design to complete her graduate work. Postmodernism is a term that is open to inter- pretation. Some feel that postmodernism is a tweak on modernist ideals. Others feel that postmodernism is a rebellion or reaction to previous political ideas that were deemed to be corrupt. Post modernism related to graphic design is more open to view points. There is not one specific standard that applies to all postmodern art. The notion about this movement is that it is what you make it. As a graphic designer, April reacted to the changes around her, used the ideas from modernism while embracing new outlooks and new changes. Tak- ing advantage of both old and new tools, April created postmodern and transmedia works. Post Modernism occurred after the “New Wave”. It was This piece was not created by April Greiman, but was instead created to reflect Greiman’s popular in the late 1980’s, 1990’s and it even extends to work. It really has a double meaning, April being the month as well as her name. The work was created in 1998 for a lecture April was giving. This piece was sponsored by the Philadel- current art practices. phia chapter of the American Institute of Graphic Arts. -

Revisiting the So-Called “Legibility Wars” of the '80S and '

58 PRINT 70.3 FALL 2016 PRINTMAG.COM 59 HAT DID YOU DO during the Legibility Wars?” asked one of my more inquisitive design history students. “Well, it wasn’t actually a war,” I said, recalling the period during the mid-’80s through the mid- to late-’90s when there were stark divisions “Wbetween new and old design generations—the young anti- Modernists, and the established followers of Modernism. “It was rather a skirmish between a bunch of young designers, like your age now, who were called New Wave, Postmodern, Swiss Punk, whatever, and believed it necessary to reject the status quo for something freer and more contemporary. Doing that meant criticizing old-guard designers, who believed design should be simple—clean on tight grids and Helveticized.” “Do you mean bland?” he quizzed further. “Maybe some of it was bland!” I conceded. “But it was more like a new generation was feeling its oats and it was inevitable.” New technology was making unprecedented options possible. Aesthetic standards were changing because young designers wanted to try everything, while the older, especially the devout Modern ones, believed everything had already been tried. “I read that Massimo Vignelli called a lot of the new digital and retro stuff ‘garbage,’” he said. “What did you say or do about it back then?” “I was more or less on the Modernist side and wrote about it in a 1993 Eye magazine essay called ‘Cult of the Ugly.’” I wasn’t against illegibility per se, just the stuff that seemed to be done badly. I justified biased distinctions not between beauty and ugly, but between good ugly and bad ugly, or what was done with an experimental rationale and with merely style and fashion as the motive. -

Woodbury University 2014-2015 Graduate Catalog

Graduate Bulletin Graduate Bulletin Woodbury University 2014-2015 Woodbury University’s U.S. Code. Veterans and dependents are required Graduate Bulletin to comply with Veterans Administration regula- Woodbury University’s Graduate Bulletin serves as tions under sections 21.4135, 21.4235 and 21.4277 a supplement to the Woodbury University Course regarding to required class attendance and accept- Catalog. Institution-wide policies and procedures able academic progress. may be found in that publication and policies cover- ing student conduct may be found in the current Nondiscrimination Policy Woodbury University Student Handbook. Woodbury University is committed to providing an environment which is free of any form of discrimi- Accreditation nation and harassment based upon an individual’s Woodbury University is accredited by the Senior race, color, religion, sex, gender identity, pregnancy, Commission of the Western Association of Schools national origin, ancestry, citizenship status, age, and Colleges (WASC: 985 Atlantic Avenue, Suite 100; marital status, physical disability, mental disability, Alameda, CA 94501; 510-748-9001) and is approved medical condition, sexual orientation, military or by the Postsecondary Commission, California De- veteran status, genetic information, or any other partment of Education. WASC granted Woodbury characteristic protected by applicable state or fed- its original regional accreditation in 1961. In 1994 eral law, so that all members of the community are the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) treated at all times with dignity and respect. It is the accredited the Bachelor of Architecture program. university’s policy, therefore, to prohibit all forms of The Master of Architecture program received its such discrimination or harassment among university NAAB accreditation in the spring of 2012. -

A Biography of the American Snow Globe: from Memory to Mass Production, from Souvenir to Sign

A BIOGRAPHY OF THE AMERICAN SNOW GLOBE: FROM MEMORY TO MASS PRODUCTION, FROM SOUVENIR TO SIGN Anne Hilker Prof. Marilyn Cohen, Thesis Advisor Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution; and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 © 2014 Anne K. Hilker All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………1 CHAPTER I. A MATERIAL HISTORY OF THE SNOW GLOBE…………………....6 CHAPTER II. THE SNOW GLOBE AS OBJECT OF MEMORY…………………….27 CHAPTER III. THE COMMODIFICATION OF THE SNOW GLOBE: COMMODIFYING, COLLECTING, SUBVERTING……………..…57 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………..79 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..ii BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………….…………..……..92 ILLUSTRATIONS…………………………………………………………….……….111 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Eiffel Tower snow globe, 1889. Image from blog, My Favorite Things!, entry dated Dec. 15, 2011, crediting the Bergstrom-Mahler Museum, http://myfavoritethings- conniemotz.blogspot.com/2011/12/1889-paris-exhibition-snow-globe.html, last visited April 19, 2014. 2. Bernard Koziol’s view out the back of his Volkswagen “Beetle,” circa 1950. “The Story of the Dream Globes,” posting on Company Koziol website, undated, http://www.snow-globe.com/history_snow_globe.htm, last accessed October 3, 2013. 3. Florida day/date snow globe, entry on Flickr.com, June 29, 2009, https://www.flickr.com/photos/thriftedsisters/3673223886/, last accessed April 19, 2014, picturing globe of structure similar to that appearing in Moore and Rinker, Snow Globes, 48. 4A, B. Baccarat Silhouette Squirrel Cane Paperweight, side and top views, iGavel auctions, posted June 14, 2012, http://www.igavelauctions.com/category/sale- highlights/page/2/, last accessed April 19, 2014. -

In the 1980S, April Greiman Reasoned That the Computer Would Become an Integral Tool for Graphic Design, but Many Didn’T Want to Hear It

In the 1980s, April Greiman reasoned that the computer would become an integral tool for graphic design, but many didn’t want to hear it Words by Photos by Meg Miller Nolwen Cifuentes GOSSIP 109 SENSE & SENSIBILITY This is my favorite line ever uttered in one of those flip- By the mid-’80s, Greiman was used to the heated debates and spir- ping-through-the-portfolio presentations that designers love to give: ited industry chatter that her designs tended to incite. Studying at “Only a spiral galaxy can bring forth new stars perpetually.” It was Kansas City Art Institute and later under Armin Hofmann at Basel said by April Greiman during a 1996 talk at SCI-Arc, the Southern School of Design in Switzerland, Greiman possessed the skills of the California Institute of Architecture, where she was introduced by Modernist tradition, but always had an itch for experimentation. three male architects who all claimed to be her boyfriend (including Moving to Los Angeles further inspired her use of bright colors, drop her husband, architect and SCI-Arc co-founder Michael Rotondi). It was a shadow, diagonal type, mixed media, and penchant for DayGlo orange. reference to the spiral galaxy in her famed poster “Does It Make With designer and photographer Jayme Odgers, she ushered in the Sense?,” a five foot, four inch visual timeline of creativity and cre- California New Wave movement, ran a functional art company called ation, starting with the Big Bang and ending with the designer her- Visual Energy, and designed issues of Wet, the infamous late ’70s/ self. -

Tribute Program

An Industry Celebration and Tribute to BRUCE FRASER 1954 – 2006 When the mind is at peace, the world too is at peace. Nothing real, nothing absent. Not holding on to reality, not getting stuck in the void, you are neither holy or wise, just an ordinary fellow who has completed his work. Layman Pang-yun (740-808) The Enlightened Heart, edited by Stephen Mitchell, p. 34 GREAT SCOT! Ode to a Color Geek Steve Upton There’s a time in every Scot’s life Fair fa your honest sonsie face, when he gets called a haggis by great chieftain of the color race. Above them all you take your place, someone. Revered and reviled, the with patience, acumen and charm. You are well worthy of a grace haggis is a symbol of Scottish tradi- as long’s my arm. tion, culture and odd cooking habits. From Photoshop to Camera Raw, When asked to contribute to an event the bits refused to match at all. Real World Color really broke, honoring Bruce’s life and contribu- this workflow stuff was such a joke. tions to the industry, the first thing When color matches were most bleak, who should appear but the Color Geek. that came to mind was Robbie Burn’s Your wit and vigor would lay waste, “To a Haggis”. Rewriting it for Bruce to software bugs released in haste. is just the sort of thing that would But patience and advice would be your weapons agin’ mediocrity bring a wry smile to his face. A kind When the dust had settled (and the bugs were gone), of honor and roast in one. -

Graffiti: a Visual Vernacular As Graphic Design Source Sung Hun Choi Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 Graffiti: a visual vernacular as graphic design source Sung Hun Choi Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Choi, Sung Hun, "Graffiti: a visual vernacular as graphic design source" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15068. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15068 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Graffiti: A visual vernacular as graphic design source by Sung Hun Choi A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Graphic Design Program of Study Committee: Roger Baer, Major Professor Paul Bruski Fred Malven Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Sung Hun Choi, 2007. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 1446067 UMI Microform 1446067 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road -

Download the Teacher Notes

TEACHER EXHIBITION NOTES CALIFORNIA 24 APRIL – 15 OCTOBER 2017 INTRODUCTION The central premise is that California has pioneered tools of personal liberation, from LSD to surf- boards and iPhones. This ambitious survey brings together political posters and portable devices, but also looks beyond hardware to explore how user interface designers in the San Francisco Bay Area are shaping some of our most common daily experiences. By turns empowering, addictive and trou- bling, Californian products have affected our lives to such an extent that in some ways we are all now Californians. WHAT TO EXPECT The exhibition is separated into five sections that look at an aspect of the Californian ethic; whether it be the spirit of the working practice or the hippy mind-set of the Californian local. The five sections contain exhibits that look at the chronology of those themes. There is no set route around the sec- tions perhaps in keeping with the Californian ‘liberated’ freedom. HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE EXHIBITION The exhibition is split into the following sections; SAY WHAT YOU WANT Tools of self-expression and rebellion Californian designers have pioneered various forms of freedom of expression, producing distinct graphic cultures that have been widely influential. The political agitation of the 1960s produced a wave of activist design in support of free speech and civil rights for African Americans, women and the gay community. Artists and designers such as Sister Corita Kent and Emory Douglas of the Black Panthers created a politically charged language with a pop aesthetic. By the 1980s, political content gave way to more individualistic forms of expression. -

Wolfgang Weingart's Typographic Landscape

Wolfgang Weingart’s typographic landscape Keith Tam 1 (This article was originally published in Polish in as ‘deconstructive’ would be too simplistic a com- 2+3D magazine, issue i-2003, Nr 6. Permission ment. His typographic experiments were strongly for the use of the images were granted by grounded, and were based on an intimate under- Wolfgang Weingart.) standing of the semantic, syntactic and pragmatic functions of typography. Whereas ‘traditional’ He started it all. It was he who ignited the spark Swiss typography mainly focused on the syntactic of ‘typographic anarchy’ that exploded on the function, Weingart was interested in how far the verge of the nineteen nineties. It was he who graphic qualities of typography can be pushed fathered what was subsequently dubbed ‘Swiss and still retain its meaning. This is when the se- Punk’, ‘New Wave’ or whatever you care to call mantic function of typography comes in: Weingart it – perhaps even post-modernism. His name believes that certain graphic modifications of type is Wolfgang Weingart. Weingart was born in the can in fact intensify meaning. ‘What’s the use of midst of the World War II in Germany. Most fa- being legible, when nothing inspires you to take mous for his experimental, expressive work that notice of it?’ How true. broke the mould of classical Swiss typography, Weingart’s work is characterized by his paint- Weingart began his typographic career in the early erly application of graphical and typographical sixties as an apprentice of hand composition at elements. The emotionally-charged lines, the a typesetting firm. He then decided to further potent, image-like qualities of his type, the almost his studies at the Basel School of Design in cinematic impact of his layouts, all speak of his Switzerland, the cradle of classical Swiss typog- great passion of creating with graphical forms. -

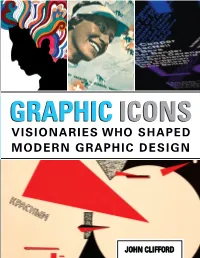

Visionaries Who Shaped Modern Graphic Design

Who are history’s most influential graphic designers? In this fun, fast-paced introduction to the most iconic designers of our time, author ICONS GRAPHIC John Clifford takes you on a visual history tour that’s packed with the posters, ads, logos, typefaces, covers, and multimedia work that have made these designers great. You’ll find examples of landmark work by such industry luminaries asE l Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, A.M. Cassandre, Alvin Lustig, Cipe Pineles, Paul Rand, Saul Bass, Milton Glaser, Wim Crouwel, Stefan Sagmeister, John Maeda, Paula Scher, and more. “ Packed with inspiration and information about the pioneers and radicals and experimenters who broke the rules of design.” — Stephen Doyle, Creative Director, Doyle Partners MODERN GRAPHIC VISIONARIES WHO GRAPHICGRAPHIC ICONSICONS S D VISIONARIES WHO SHAPED HAPED HAPED ESI G N MODERN GRAPHIC DESIGN JOHN CLIFFORD Who coined the term graphic design? Who turned film titles into an art? Who pioneered infor- mation design? Who was the first female art director of a mass-market American magazine? In Graphic Icons: Visionaries Who Shaped Modern Graphic Design, you start with the who and quickly learn the what, when, and why behind graphic design’s most important breakthroughs and the impact their creators had, and continue to have, on the world we live in. John Clifford is an award-winning creative director and principle Your favorite designer didn’t at Think Studio, a New York City design firm with clients that make the list? Join the conversation include The World Financial Center, L.L.Bean, Paul Labrecque, at graphiciconsbook.com The Monacelli Press, and Yale School of Architecture.