The Case for the Tip Credit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordinance No. 11-14 N.S. an Ordinance of the City Council of the City of Richmond Amending Article Vii of the Municipal Code To

ORDINANCE NO. 11-14 N.S. AN ORDINANCE OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND AMENDING ARTICLE VII OF THE MUNICIPAL CODE TO REQUIRE THE PAYMENT OF A CITY-WIDE MINIMUM WAGE ____________________________________________________________________ WHEREAS, families and workers need to earn a living wage, and public policies which help achieve that goal are beneficial; and WHEREAS, payment of a minimum wage advances the City of Richmond’s interest by creating jobs that help workers and their families avoid poverty and economic hardship and enable them to meet basic needs; and WHEREAS, payment of a minimum wage advances the City’s interest by improving the quality of services provided in the City to the public by reducing high turnover, absenteeism, and instability in the workplace; and WHEREAS, the current Federal and State hourly minimum wage are both below the minimum wage of 1979 in current dollars; and WHEREAS, the cost of living in the City of Richmond is estimated at 20% greater than the overall national average; and WHEREAS, households supported by a single full-time current minimum wage earner are at or below the official national poverty line; and WHEREAS, increasing the minimum wage increases consumer purchasing power, increases workers’ standards of living, reduces poverty, and stimulates the economy; and WHEREAS, the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank conducted a study in 2011 estimating that every dollar increase in the minimum wage results in $2,800 in new consumer spending by that household the following year, and this revenue is -

Ballot Intiative 77 Is Good for Workers

BALLOT INTIATIVE 77 IS GOOD FOR WORKERS What is Ballot Initiative 77? Ballot initiative 77 will incrementally increase the tipped minimum wage by $1.50 per year until it reaches $15 per hour in 2025. Currently, the law requires employers to pay tipped workers a “tipped minimum wage” – $3.33 an hour. When workers receive less than the current full minimum wage ($12.50 per hour), employers must pay the difference between a worker’s tips and the full minimum wage. Under Ballot Initiative 77, there would be one wage for all workers. Tipped Workers’ Annual Wages in DC Who are Tipped Workers in the District? Annual earnings needed Tipped workers are employed in a range of industries in $70,000 to cover costs of living the District. Let’s think about the people we tip regularly. in the District Yes, there are food-service workers like servers and 50,000 Bartenders bartenders, but there are also hairstylists, hotel workers, Waiters and taxi drivers and other employees who all rely on tips. Waitresses 30,000 Shampooers Tipped workers—who are overwhelmingly women of Taxi Drivers color— are nearly twice as likely to live in poverty than all 10,000 other workers. The annual median wage for bartenders 0 and servers is approximately $31,000 and $25,000, Source: BLS, May 2017 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates respectively. This is far below the annual salary of District of Columbia $68,000 needed to cover costs of living in the District. Workers are Less Likely to Live in Poverty with One Fair Wage Which States Have One Fair Wage? Non Tipped Workers Alaska, Montana, Nevada, Minnesota, California, Oregon 7% and Washington. -

Local Minimum Wage Ordinance November 2019)

Local Minimum Wage Ordinance November 2019) Jurisdiction Ordinance Considered Community Outreach Ordinance Details Other Comments Atherton No, Atherton does not n/a n/a n/a have businesses in town – Jennifer Frew only residential and [email protected] schools. Belmont Yes, adopted 11/14/2017. Did not do a substantial amount of outreach for the City Based on Council direction to increase MW to $15 by 2020. 10/24 and 11/14 City Council staff reports Study Session on 10/24/17 Council actions beyond regular notification, and notifying the 7/1/2018: $12.50 per hour are good examples of how to organize Jennifer Rose, (Item 9A). Chamber of Commerce directly. Used other jurisdictions for 1/1/2019: $13.50 per hour information. Management Analyst II Action taken on examples, and tied increases to align with neighboring Cities by 1/1/2020: $15 per hour Belmont City Council was confident in their Housing & Economic 11/14/2017 (Item 9B) and 2021. 1/1/2021: $15.90 per hour position to accelerate MW going into this Development Finance 11/28/17 (Item 7F). Did do a substantial outreach effort once the Ordinance was 1/1/2022 and each following year: CPI up to 3.5% process so it was not controversial. Department adopted and prior to the first increase, including a direct All employers are subject to MW ordinance, and all https://www.belmont.gov/our- (650) 595-7453 mailer to the physical business address for all business license employees who work two or more hours entitled to MW. -

City of San Mateo Minimum Wage Ordinance Frequently Asked Questions

CITY OF SAN MATEO MINIMUM WAGE ORDINANCE FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS What is the City of San Mateo Minimum Wage Ordinance and how does this affect my business? The San Mateo City Council adopted an ordinance to create a City minimum wage. The ordinance requires employers that maintain a place of business in the City of San Mateo or perform any work/service within the City limits to pay the City’s minimum wage to its employees (as defined by State law). The ordinance went into effect on January 1, 2017. What is the Minimum Wage in the City of San Mateo? The minimum wage increases on January 1st of every year and is adjusted based on the regional Consumer Price Index (CPI). Starting on January 1, 2020, all employers are required to pay employees $15.38 per hour. Does the Minimum Wage apply elsewhere within the County of San Mateo? No, the City of San Mateo minimum wage only applies to employees who work within the geographic boundaries of the City of San Mateo. There are several Minimum Wage laws: Federal, State, and City of San Mateo. What is the difference and which one applies to local businesses? City of San Mateo employers are subject to Federal, State and San Mateo minimum wage laws. When there are conflicts in the laws, the employer must follow the strictest standard, meaning that employers must follow the standard that is most favorable to the employee. Since the City of San Mateo’s ordinance is higher than the State and Federal law, covered employers are required to pay the City’s minimum wage. -

Minimum Wage Public Comment

From: Martha Hage To: MinWage Subject: Oppose $15 Date: Wednesday, June 21, 2017 11:57:39 PM To whom it may concern: A reasonable minimum wage is $12. The only locations in the United States of America that have a minimum wage of $15 are the East Coast and the West Coast. The cost of living is significantly higher in those areas. The cost of living would increase in Minneapolis and force people out of our city. Businesses would move out of Minneapolis or close. As stated above, a reasonable minimum wage for Minneapolis is $12. Sincerely, Martha M. Hage [email protected] 612.339.4959 Sent from my iPad From: Dahler, Ken on behalf of Council Comment To: MinWage Subject: FW: Minimum Wage To the city council attached document Date: Thursday, June 22, 2017 7:26:10 PM Attachments: To the City Council.docx Ken Dahler l Council Committee Coordinator l City of Minneapolis – Clerk’s Office l 350 S. Fifth St. – Room 304 612-673-2607 l [email protected] From: [email protected] [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Wednesday, June 21, 2017 9:13 PM To: Council Comment Subject: Minimum Wage To the city council attached document Margaret Hastings, MA, LPCC,CEAP,SAP This is confidential information. If received in error, delete and call Margaret Hastings at ph. 952-457-2288 From: JJ Haywood To: Quincy, John Subject: Minneapolis Minimum Wage Date: Monday, June 19, 2017 8:29:03 PM Dear Council Member Quincy: I'm writing you requesting that the Council reconsider the phase in to the $15/hr minimum wage ordinance. -

COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout and Mandatory Policies

COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout and Mandatory Policies 1 Grant T. Collins (612) 373-8519 [email protected] Penelope J. Phillips (612) 373-8428 [email protected] 2 FDA Issues EUAs ▪ Pfizer ▪ EUA issued on Dec. 11, 2020 ▪ BLA application expected “in the first half of 2021” ▪ Moderna ▪ EUA issued on Dec. 18, 2020 ▪ BLA application expected “in the first half of 2021” ▪ Johnson & Johnson ▪ EUA issued on Feb. 27, 2021 ▪ CDC and FDA recommend “pause” on April 13, 2021 3 Vaccine Rollout 4 5 6 7 Vaccine Hesitancy Remains ▪ February 2021 Pew Research Poll: ▪ 69% said they would “definitely” or “probably” get a COVID-19 vaccine. ▪ 30% said they would “definitely” or “probably” not get the COVID-19 vaccine. 8 9 10 11 Planning for Employer Vaccination Policies 12 Educate and Engage Employees ▪ Prepare employees for your organization’s policies relating to the COVID-19 vaccine. ▪ Begin a process of educating and engaging employees about the vaccine, its efficacy, and safety. ▪ CDC has a “toolkit” for employers. 13 CDC Resources 14 CDC Resources(cont.) ▪ CDC’s provides: ▪ Sample letter to employees. ▪ Sample newsletter content. ▪ “Myths & Facts” regarding COVID-19 vaccine. ▪ V-Safe Program. 15 Vaccine Planning ▪ Survey your workforce about the vaccine. ▪ How many are going to voluntarily receive the vaccine? ▪ How many would like more information regarding the vaccine. ▪ Educate, educate, educate. 16 Avoid ADA Issues ▪ Vaccination Status Survey ▪ Not a medical inquiry per se, but survey should ensure that the individual does not explain “why” not receiving a vaccine. ▪ Warn employees not to provide any medical information. ▪ Employee’s response may be considered confidential medical information under ADA. -

Workers' Rights for Workforce Development Total Time: 1 Hour, 30

UNIT 3 – Wage and Hour Laws and Protection UNIT 3 Photograph by Robert L. Simpson Workers’ Rights for Workforce Development Total Time: 1 hour, 30 minutes Wage and Hour Laws & Protection I worked at a cleaning company where I would work for another person who was the one who had the contract. I only worked for her on weekends. One time I told her I couldn’t work and when I returned to work she told me that she no longer needed me and never paid me the last week I had worked. I felt abused, as this person only paid me what she wanted and when she wanted and only gave me work when it was convenient for her. I was without work whenever she wanted and she never paid me the $90 she owed me. – Job-seeking client, February 2015 Copyright UIUC Labor Education Program, 2015 3-1 Workers’ Rights for Workforce Development WORKERS’ RIGHTS FOR WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT Purpose Publication Date This curriculum is based on learning in social, cooperative and This Workers’ Rights for Workforce Development active ways, with students’ questions and concerns as the center Curriculum is current as of December 1, 2015. focus. The teacher is a facilitator who inspires students to analyze, look for equality, find history, and speak in a strong and informed Preferred Citation voice. Our goal is to help you, as workforce development staff, Authors: Alison Dickson, Sue Davenport, and engage your students in learning that they have rights and that Marsha Love. there are resources accessible to them for help in protecting Workers’ Rights for Workforce Development: A those rights. -

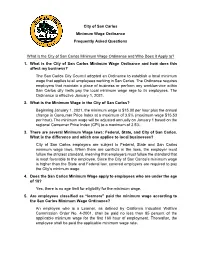

City of San Carlos Minimum Wage Ordinance Frequently Asked Questions

City of San Carlos Minimum Wage Ordinance Frequently Asked Questions What is the City of San Carlos Minimum Wage Ordinance and Who Does it Apply to? 1. What is the City of San Carlos Minimum Wage Ordinance and how does this affect my business? The San Carlos City Council adopted an Ordinance to establish a local minimum wage that applies to all employees working in San Carlos. The Ordinance requires employers that maintain a place of business or perform any work/service within San Carlos city limits pay the local minimum wage rage to its employees. The Ordinance is effective January 1, 2021. 2. What is the Minimum Wage in the City of San Carlos? Beginning January 1, 2021, the minimum wage is $15.00 per hour plus the annual change in Consumer Price Index at a maximum of 3.5% (maximum wage $15.53 per hour). The minimum wage will be adjusted annually on January 1 based on the regional Consumer Price Index (CPI) to a maximum of 3.5%. 3. There are several Minimum Wage laws: Federal, State, and City of San Carlos. What is the difference and which one applies to local businesses? City of San Carlos employers are subject to Federal, State and San Carlos minimum wage laws. When there are conflicts in the laws, the employer must follow the strictest standard, meaning that employers must follow the standard that is most favorable to the employee. Since the City of San Carlos’s minimum wage is higher than the State and Federal law, covered employers are required to pay the City’s minimum wage. -

Labouring Oar

Federal Bar Association Labor and Employment Law Section The Summer 2018 Labouring Oar Message from the Chair By Kathryn M. Knight cognizant of potential unintended consequences of those movements, including, as one example, fewer mentors for It’s summertime, and the Labor women. In addition, the panel will address practical topics, and Employment Law Section is HOT! such as effective anti-discrimination and anti-harassment That is, the Section is having a busy policies, how to investigate a complaint properly, and and exciting summer, and we want to what constitutes “prompt remedial action.” Finally, the share with you, our Section members panel will explore settlement agreements and potential tax and readers, all that we have going on. consequences of confidentiality provisions. I hope you already have made plans In addition, the Programming and CLE committee will to join us in New York for the Annual kick off its Traveling CLE program on August 3, 2018 in Meeting on September 13-15, 2018. I’m happy to report that Puerto Rico. There, Greg Peters, Katherine González, and the Section, in collaboration with the Southern District of Phillip Kitzer will address “Hot Topics 2018,” including New York, was selected to present what promises to be a NLRA changes under the Trump Board, sexual orientation riveting continuing legal education program on a timely topic: discrimination in the workplace, and recent developments “#MeToo: Implementation and Administration of an Effective affecting labor and employment law in Puerto Rico. Future Anti-Harassment Policy.” The program will be presented locations and dates for the Traveling CLE program include by a distinguished panel comprised of The Honorable Lisa El Paso, Texas on November 7, 2018, followed by Portland, Margaret Smith, United States Magistrate Judge, Southern Oregon and Rockford, Illinois on dates still to be determined. -

Seattle's Minimum Wage Increase

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MINIMUM WAGE INCREASES, WAGES, AND LOW-WAGE EMPLOYMENT: EVIDENCE FROM SEATTLE Ekaterina Jardim Mark C. Long Robert Plotnick Emma van Inwegen Jacob Vigdor Hilary Wething Working Paper 23532 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23532 NATIONALBUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESESARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge MA 02138 June 2017, Revised May 2018 We thank the state of Washington’s Employment Security Department for providing access to data, and Matthew Dunbar for assistance in geocoding business locations. We thank the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Smith Richardson Foundation, the Russell Sage Foundation, and the City of Seattle for funding and supporting the Seattle Minimum Wage Study. Partial support for this study came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, R24 HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington. We are grateful to conference session participants at the 2016 Association for Public Policy and Management, 2017 Population Association of America, and 2018 Allied Social Science Association meetings; to seminar participants at Columbia University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Montana State University, National University of Singapore, Stanford University, University of British Columbia, University of California-Irvine, University of Chicago, University of Houston, University of Pittsburgh, University of Rochester, and the World Bank; members and guests of the Seattle Economic Council, and to the Seattle City Council and their staff for helpful comments on previous iterations of this work. We also thank Sylvia Allegretto, David Autor, Marianne Bitler, David Card, Raj Chetty, Jeff Clemens, David Cutler, Arin Dube, Ed Glaeser, Hillary Hoynes, Kevin Lang, Thomas Lemieux, David Neumark, Michael Reich, Emmanuel Saez, Diane Schanzenbach, John Schmitt, and Ben Zipperer for discussions which enriched the paper. -

Raises from Coast to Coast in 2020: Minimum Wage Will Increase in Record-High 47 States, Cities, and Counties This January

Raises From Coast to Coast in 2020: Minimum Wage Will Increase in Record-High 47 States, Cities, and Counties This January By Yannet Lathrop December | 2019 REPORT | DECEMBER 2019 Raises From Coast to Coast in 2020: Minimum Wage Will Increase in Record-High 47 States, Cities, and Counties This January On January 1, 2020 (December 31, 2019 in New York) the minimum wage will increase in 21 statesi and 26 cities and counties. In 17 of those jurisdictions, the minimum wage will reach or surpass $15 per hour. Later in 2020, four more states and 23 additional localities will also raise their minimum wages—15 of them to $15 or more. This is the greatest number of states and localities ever to raise their wage floors, both in January and for the year as a whole. More and more jurisdictions have been raising their minimum wages since the Fight for $15 movement began in November 2012. In total, 24 states and 48 cities and counties will raise their minimum wages sometime in 2020. (Illinois and Saint Paul, MN will increase their minimum wages twice in 2020 but are counted only once in the year’s grand total.) These increases will put much-needed money into the hands of the lowest-paid workers, many of whom struggle with high and ever-increasing costs of living. Below is a summary of what to expect in 2020: Minimum wage will increase in 21 states and 26 cities and counties on or around New Year’s Day, for a total of 47 jurisdictions. (See Table 2.) • Among the 21 states and 26 cities and counties raising their minimum wages on or around January 1, 2020 are Illinois and Saint Paul, MN, which will raise their wage floors twice—in January and July. -

City of Belmont Minimum Wage

City of Belmont Minimum Wage Frequently Asked Questions Q: What is in the Belmont Minimum Wage Ordinance? A: The Ordinance requires all Employers of Employees who perform at least two (2) hours of work per week within the geographical boundaries of Belmont to pay those employees the City Minimum Wage. The City Council adopted the Ordinance on November 14, 2017 to increase minimum wage to $15.00/hour by 2020. As of January 1, 2019, the City Minimum Wage is $13.50 per hour. Q: Which employers are subject to the City of Belmont Business License? A: Employers that have a place of business in Belmont or employers that must obtain a business license and pay the applicable business tax to conduct business within the City’s limits. Employers are required to pay employees no less than the City Minimum Wage for each hour worked within the geographic boundaries of the City. Q: How much is the City Minimum Wage rate? A: Effective dates and corresponding Minimum Wage rates are summarized in the table below: Q: How often will the Belmont Minimum Wage be adjusted? A: The City Minimum Wage will be adjusted to $12.50 per hour on July 1, 2018. Beginning January 1, 2019, the City Minimum Wage will increase to $13.50 per hour, and on January 1, 2020, it will increase to $15.00 per hour. Every January 1 thereafter, the City Minimum Wage will increase by an amount corresponding to the prior year’s Regional Consumer Price Index as reported by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics.