University College Cork – National University of Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cork City Licence Register No

Annual Environmental Report 2015 Agglomeration Name: Cork City Licence Register No. D0033-01 Table of Contents Section 1. Executive Summary and Introduction to the 2015 AER 1 1.1 Summary report on 2015 1 Section 2. Monitoring Reports Summary 3 2.1 Summary report on monthly influent monitoring 3 2.2 Discharges from the agglomeration 4 2.3 Ambient monitoring summary 5 2.4 Data collection and reporting requirements under the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive 7 2.5 Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (PRTR) - report for previous year 7 Section 3 Operational Reports Summary 9 3.1 Treatment Efficiency Report 9 3.2 Treatment Capacity Report 10 3.3 Extent of Agglomeration Summary Report 11 3.4 Complaints Summary 12 3.5 Reported Incidents Summary 13 3.6 Sludge / Other inputs to the WWTP 14 Section 4. Infrastructural Assessments and Programme of Improvements 15 4.1 Storm water overflow identification and inspection report 15 4.2 Report on progress made and proposals being developed to meet the improvement programme requirements. 22 Section 5. Licence Specific Reports 26 5.1 Priority Substances Assessment 27 5.2 Drinking Water Abstraction Point Risk Assessment. 28 5.3 Shellfish Impact Assessment Report. 28 5.4 Toxicity / Leachate Management 28 5.5 Toxicity of the Final Effluent Report 28 5.6 Pearl Mussel Measures Report 28 5.7 Habitats Impact Assessment Report 28 Section 6. Certification and Sign Off 29 Section 7. Appendices 30 Appendix 7.1 - Annual Statement of Measures 31 Appendix 7.1A – Influent & Effluent Monitoring Incl. UWWT Compliances 32 Appendix 7.2 – Ambient River Monitoring Summary 33 Appendix 7.2A – Ambient Transitional & Coastal Monitoring Summary 34 Appendix 7.3 – Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (PRTR) Summary Sheets 35 Appendix 7.4 – Sewer Integrity Tool Output 36 WasteWater Treatment Plant Upgrade. -

Cork City Development Plan

Cork City Development Plan Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Cork City Council 2015 - 2021 Environmental Assessments Contents • Part 1: Non-Technical Summary SEA Environmental Report 3 • Part 2: SEA Environmental Report 37 SEA Appendices 191 • Part 3: Strategic Flood Risk Assessment (SFRA) 205 SFRA Appendices 249 • Part 4: Screening for Appropriate Assessment 267 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 1 Volume One: Written Statement Copyright Cork City Council 2014 – all rights reserved. Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi. Licence number 2014/05/CCMA/CorkCityCouncil © Ordnance Survey Ireland. All rights reserved. 2 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 Part 1: SEA Non-Technical Summary 1 part 1 Non-Technical Summary Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Contents • Introduction 5 • Context 6 • Baseline Environment 6 • Strategic Environmental Protection Objectives 15 • Alternative Scenarios 21 • Evaluation of Alternative Scenarios 22 • Evaluation of the Draft Plan 26 • Monitoring the Plan 27 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 3 1 Volume Four: Environmental Reports 4 Draft Cork City Development Plan 2015-2021 Part 1: SEA Non-Technical Summary 1 PART 1 SEA NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY 1. Introduction Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is the formal, systematic assessment of the likely effects on implementing a plan or programme before a decision is made to adopt the plan or programme. This Report describes the assessment of the likely significant effects on the environment if the draft City Development Plan is implemented. It is a mandatory requirement to undertake a SEA of the City Development Plan, under the Planning and Development (Strategic Environmental Assessment) Regulations, 2004 (as amended). SEA began with the SEA Directive, namely, Directive 2001/42/EC Assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment. -

Oct-Nov 2012

25 Years Serving the Local Community Mayfield Matter s Mayfield Community Training Centre FREE COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER, HIGHLIGHTING LOCAL NEWS St. Joseph’s Community Association ISSUE 64: Oct/Nov 2012 On 6th November, Mayfield Community Training Centre had an open day to celebrate 25 years of serv- Mayfield Banks Respond to Community Fears We return to the story of the two impending Bank closures planned for Mayfield. There is a palpable disappointment and resentment in the air all around the locality at the decisions taken by senior management at PTSB and AIB in this regard. Given the massive debts run up by our Banks during the “Celtic Tiger” years, these closures are not unexpected, though neither are they desirable. When Mayfield Matters contacted the Permanent Trustee Savings Bank (PTSB) for a comment, we were re-directed to its website. This offered nothing by way of apology to us in Mayfield, and indeed, lest we think that our branch is the only one for the chop, there will be fifteen other closures nationwide as well. Its version of good news is that; “There will be absolutely no change to your existing account(s) and all your account details will stay exactly the same”. If you have a PTSB account in Mayfield, you are directed to go to its North Main Street branch now, apparently for your convenience. The Credit Unions The picture with AIB is much clearer. Its local manager stressed that AIB has been building close links with the Post Office network for several years, seeking to share elements of its services with An Post. -

Cork County Grit Locations

Cork County Grit Locations North Cork Engineer's Area Location Charleville Charleville Public Car Park beside rear entrance to Library Long’s Cross, Newtownshandrum Turnpike Doneraile (Across from Park entrance) Fermoy Ballynoe GAA pitch, Fermoy Glengoura Church, Ballynoe The Bottlebank, Watergrasshill Mill Island Carpark on O’Neill Crowley Quay RC Church car park, Caslelyons The Bottlebank, Rathcormac Forestry Entrance at Castleblagh, Ballyhooley Picnic Site at Cork Road, Fermoy beyond former FCI factory Killavullen Cemetery entrance Forestry Entrance at Ballynageehy, Cork Road, Killavullen Mallow Rahan old dump, Mallow Annaleentha Church gate Community Centre, Bweeng At Old Creamery Ballyclough At bottom of Cecilstown village Gates of Council Depot, New Street, Buttevant Across from Lisgriffin Church Ballygrady Cross Liscarroll-Kilbrin Road Forge Cross on Liscarroll to Buttevant Road Liscarroll Community Centre Car Park Millstreet Glantane Cross, Knocknagree Kiskeam Graveyard entrance Kerryman’s Table, Kilcorney opposite Keim Quarry, Millstreet Crohig’s Cross, Ballydaly Adjacent to New Housing Estate at Laharn Boherbue Knocknagree O Learys Yard Boherbue Road, Fermoyle Ball Alley, Banteer Lyre Village Ballydesmond Church Rd, Opposite Council Estate Mitchelstown Araglin Cemetery entrance Mountain Barracks Cross, Araglin Ballygiblin GAA Pitch 1 Engineer's Area Location Ballyarthur Cross Roads, Mitchelstown Graigue Cross Roads, Kildorrery Vacant Galtee Factory entrance, Ballinwillin, Mitchelstown Knockanevin Church car park Glanworth Cemetery -

Heritage Bridges of County Cork

Heritage Bridges of County Cork Published by Heritage Unit of Cork County Council 2013 Phone: 021 4276891 - Email: [email protected]. ©Heritage Unit of Cork County Council 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Paperback - ISBN No. 978-0-9525869-6-8 Hardback - ISBN No. 978-0-9525869-7-5 Neither the authors nor the publishers (Heritage Unit of Cork County Council) are responsible for the consequences of the use of advice offered in this document by anyone to whom the document is supplied. Nor are they responsible for any errors, omissions or discrepancies in the information provided. Printed and bound in Ireland by Carraig Print inc. Litho Press Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork, Ireland. Tel: 021 4883458 List of Contributors: (those who provided specific information or photographs for use in this publication (in addition to Tobar Archaeology (Miriam Carroll and Annette Quinn), Blue Brick Heritage (Dr. Elena Turk) , Lisa Levis Carey, Síle O‟ Neill and Cork County Council personnel). Christy Roche Councillor Aindrias Moynihan Councillor Frank O‟ Flynn Diarmuid Kingston Donie O‟ Sullivan Doug Lucey Eilís Ní Bhríain Enda O‟Flaherty Jerry Larkin Jim Larner John Hurley Karen Moffat Lilian Sheehan Lynne Curran Nelligan Mary Crowley Max McCarthy Michael O‟ Connell Rose Power Sue Hill Ted and Nuala Nelligan Teddy O‟ Brien Thomas F. Ryan Photographs: As individually stated throughout this publication Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2013/06/CCMA/CorkCountyCouncil Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. -

Notice of Situation of Polling Stations

DÁIL GENERAL ELECTION Friday, 26th day of February, 2016 CONSTITUENCY OF CORK NORTH WEST NOTICE OF SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS: I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the Situation and Allotment of the different Polling Stations and the description of Voters entitled to vote at each Station for the Constituency of Cork North West on Friday, 26th day of February 2016, is as follows: NO. OF NO. OF POLLING POLLING DISTRICT ELECTORAL DIVISIONS IN WHICH ELECTORS RESIDE SITUATION OF POLLING PLACE POLLING POLLING DISTRICT ELECTORAL DIVISIONS IN WHICH ELECTORS RESIDE SITUATION OF POLLING PLACE STATION DISTRICT STATION DISTRICT 143 01KM - IA Clonfert East (Part) Church View, Tooreenagreena, Rockchapel To Tooreenagreena, Rockchapel. Rockchapel National School 1 174 20KM - IT Cullen Millstreet (Part) Ahane Beg, Cullen To Two Gneeves, Cullen. Cullen Community Centre (Elector No. 1 – 218) (Elector No. 1-356) Clonfert West (Part) Cloghvoula, Rockchapel To Knockaclarig, Rockchapel. (Elector No. 219 – 299) Derragh Ardnageeha, Cullen To Milleenylegane, Derrinagree. (Elector No. 357 – 530) 144 DO Knockatooan Grotto Terrace, Knockahorrea East, Rockchapel To Tooreenmacauliffe, Tournafulla, Co. Limerick. Rockchapel National School 2 (Elector No. 300 – 582) 175 21KM - IU Cullen Millstreet (Part) Knockeenadallane, Rathmore To Knockeenadallane, Knocknagree, Mallow. Knocknagree National School 1 (Elector No. 1 – 21) 145 02KM - IB Barleyhill (Part) Clashroe, Newmarket To The Terrace, Knockduff, Upper Meelin, Newmarket. Meelin Hall 1 (Elector No. 1 – 313) Doonasleen (Part) Doonasleen East, Kiskeam Mallow To Ummeraboy West, Knocknagree, Mallow. 146 DO Glenlara Commons North, Newmarket To Tooreendonnell, Meelin, Newmarket. (Elector No. 314 – 391) Meelin Hall 2 (Elector No. 22 – 184) Rowls Cummeryconnell North, Meelin, Newmarket To Rowls-Shaddock, Meelin, Newmarket. -

Ballyvourney and Ballymakeera Frs Interim Works

BALLYVOURNEY AND BALLYMAKEERA FRS INTERIM WORKS Ecological Impact Assessment CP19008RP001 Ballyvourney and Ballymakeera FRS Interim Works - Ecological Impact Assessment F02 3rd December 2019 rpsgroup.com ECOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Document status Review Version Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by date Green Leaf Ecology Ecological Impact Michelle Bennett Michelle F02 and Michael 03/12/19 Assessment Bennett Houston, RPS Mark Magee Approval for issue Michelle Bennett 3 December 2019 © Copyright RPS Group Limited. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Limited no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS Group Limited for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. RPS Group Limited accepts no responsibility for any documents or information supplied to RPS Group Limited by others and no legal liability arising from the use by others of opinions or data contained in this report. It is expressly stated that no independent verification of any documents or information supplied by others has been made. RPS Group Limited has used reasonable skill, care and diligence in compiling this report and no warranty is provided as to the report’s accuracy. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced, by any means, without the written permission of RPS Group Limited. -

Walking Trails of County Cork Brochure Cork County of Trails Walking X 1 •

Martin 086-7872372 Martin Contact: Leader Wednesdays @ 10:30 @ Wednesdays Day: & Time Meeting The Shandon Strollers Shandon The Group: Walking www.corksports.ie Cork City & Suburb Trails and Loops: ... visit walk no. Walking Trails of County Cork: • Downloads & Links & Downloads 64. Kilbarry Wood - Woodland walk with [email protected] [email protected] 33. Ballincollig Regional Park - Woodland, meadows and Email: St Brendan’s Centre-021 462813 or Ester 086-2617329 086-2617329 Ester or 462813 Centre-021 Brendan’s St Contact: Leader Contact: Alan MacNamidhe (087) 9698049 (087) MacNamidhe Alan Contact: panoramic views of surrounding countryside of the • Walking Resources Walking riverside walks along the banks of the River Lee. Mondays @ 11:00 @ Mondays Day: & Time Meeting West Cork Trails & Loops: Blackwater Valley and the Knockmealdown Mountains. details: Contact Club St Brendan’s Walking Group, The Glen The Group, Walking Brendan’s St Group: Walking • Walking Programmes & Initiatives & Programmes Walking 34. Curragheen River Walk - Amenity walk beside River great social element in the Group. Group. the in element social great • Walking trails and areas in Cork in areas and trails Walking 1. Ardnakinna Lighthouse, Rerrin Loop & West Island Loop, Curragheen. 65. Killavullen Loop - Follows along the Blackwater way and Month. Walks are usually around 8-10 km in duration and there is a a is there and duration in km 8-10 around usually are Walks Month. Tim 087 9079076 087 Tim Bere Island - Scenic looped walks through Bere Island. Contact: Leader • Walking Clubs and Groups and Clubs Walking takes in views of the Blackwater Valley region. Established in 2008; Walks take place on the 2nd Saturday of every every of Saturday 2nd the on place take Walks 2008; in Established Sundays (times vary contact Tim) contact vary (times Sundays 35. -

Invalid from 24/04/2021

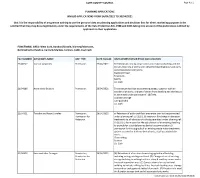

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS INVALID APPLICATIONS FROM 24/04/2021 TO 30/04/2021 that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE INVALID DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION 21/00242 Corran Carpentry Permission 27/04/2021 Demolition of existing single storey extension to dwelling and the construction of a 2 storey semi-detached dwellinghouse and carry out all associated site works Blackrock Road Town Lots Bantry Co. Cork 21/04886 Anna Marie Buckley Permission 26/04/2021 To construct dwelling incorporating garage, together with all ancillary site works, change of design from dwelling and site layout as permitted under planning ref. 18/7040. Coolnashamroge Carrigadrohid Co. Cork 21/04921 Timothy and Aoise Crowley Permission, 26/04/2021 a) Retention of additional floor area extra over to that permitted Permission for under planning ref: 0713391, b) retention for change in elevation Retention treatments to all elevations to those permitted under planning ref: 0713391 c) Permission for the sub division of an existing dwelling to provide for a standalone residential accommodation d) permission for the upgrade of an existing waste water treatment system to cater for both residential units, e) all associated site works. -

Kilometres Nutricia Site

Date 01/12/06 GF/ME R:\Map Production\2006\524\01\ Mapping Reproduced Under Licence from the Ordnance Survey Ireland Workspace\LA-NEIS_Figure 5.1_Regional Bedrock Map_Rev X Licence No. EN 0001206 © Government of Ireland ’ Co. Cork !!! Key Map Macroom !! For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Map Legend Flaser-bedded sandstone & minor mudstone Cross-bedded sandstone & minor mudstone Sandstone with mudstone & siltstone Purple mudstone and siltstone Green-grey sandstone & purple siltstone Purple mudstone and sandstone Massive unbedded lime-mudstone Sandstone and siltstone Purple siltstone & fine sandstone Purple & green sandstone & siltstone 012 Fault kilometres Nutricia Site Regional Bedrock Map Fehily Timoney & Company Figure 5.1 EPA Export 25-07-2013:21:40:08 The Gunpoint formation is defined by the incoming of metre scale sandstone bodies and the first thick (more than 1 m) intraformational breccias. Lithologically the Gun Point Formation consists of purple and green medium to coarse-grained and cross- stratified sandstones with interbedded sequences of thin purple siltstones and fine- grained parallel and cross-laminated sandstones (GSI 1997). The Castlehaven Formation conformably overlies the Gun Point Formation in the project area. The formation outcrops only on the south limb of the Macroom Syncline where it is less than 160 m in thickness (Williams et al 1989). The formation is characterised by the purple mudstones and siltstones with interbedded fine grained sandstones. 5.4. Hydrologeology According to the GSI aquifer classification system, the aquifer underlying the Nutricia site and within the surrounding area is classified as locally important (L1) (which is generally moderately productive in local zones) and a Poor aquifer (P1) (which is generally unproductive except in local zones). -

An Introduction to Our Catchment

streamscapes Lee source to sea An Introduction to our Catchment Where the Lee is young...the rich & complex ecology of the Gearagh www.streamscapes.ie “To protect your rivers, protect your mountains.” - Emperor Yu (1600BC) Foreword: What is a Catchment? When you think of it, we all live in valleys, no matter how steep or broad, SAFETY FIRST!!! The ‘StreamScapes’ programme involves a hands-on survey of your local landscape and and all of our valleys have streams and rivers. From the hills above us to waterways...safety must always be the underlying concern. If you are undertaking aquatic survey, remember that all bodies of water are potentially dangerous places. the sea below, these watercourses make their way across our landscape and Slippery stones and banks, broken glass and other rubbish, polluted water courses which define the Catchment in which we live. Here a mountain stream runs may host disease, poisonous plants, barbed wire in riparian zones, fast moving currents, misjudging the depth of water, cold temperatures...all of these are hazards to be minded! swiftly and tumbles over waterfalls, there a wide river flows easily past If you and your group are planning a visit to a stream, river, canal, or lake for purposes of assessment, ensure that you have a good ratio of experienced and water-friendly adults green fields, through our communities and down to the sea. to students, keep clear of danger, and insist on discipline and caution! In that river, along its banks and into the surrounding landscapes, may be found a wealth of biodiversity; fish, birds, insects, animals, trees, wild Welcome to StreamScapes, a dynamic environmental education programme for schools, flowers, and people, but only if our waters run pure and clean. -

Cork County Development Plan 2009

CORK COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2009 Second Edition Volume 2 Specific Objectives: 2 Heritage and Amenity Cork County Council Planning Policy Unit Technical Information: The text volumes of this plan have been designed and laid out using Microsoft Word™ software. Maps in Volume three have Cork County Council been prepared by the staff of the Planning Policy Unit using Planning Policy Unit a MapInfo™ GIS platform. The Compact Disc CD version was developed by the Planning Policy Unit using Adobe® Acrobat ® Distiller™ 5.0. Copyright: Cork County Council 2009. All rights reserved. Map base: Ordnance Survey of Ireland Permit Number 7634 © Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland. All rights reserved. This Development Plan was printed on 100% Recycled Paper CORK County Development Plan 2009 2nd Edition CORK County Development Plan i 2009 Second Edition, Jan 2012 Volume 2 Specific Objectives Heritage and Amenity ii Volume 2: Specific Objectives: Heritage and Amenity Contents of Volume 2: Chapter 1: Record of Protected Structures 1 THE DEVELOMENT PLAN IS PRESENTED IN THREE VOLUMES: Chapter 2: Architectural Conservation Areas 69 Volume 1: Overall Strategy and Main Chapter 3: Nature Conservation Areas 73 Policy Material 3.1 Nature Heritage Areas 74 Sets out the general objectives of the Development Plan under 3.2 Proposed Natural Heritage Areas 75 a range of headings together with the planning principles that 3.3 Candidate Special Areas of Conservation 82 underpin them. 3.4 Special Protection Areas and Proposed Volume 2: Specific Objectives: Special Protection Areas 84 Heritage and Amenity 3.5 Areas of Geological Interest 85 Sets out, in detail, a range of specific heritage and amenity objectives of the Development Plan, with particular attention to Chapter 4: Scenic Routes 91 the Record of Protected Structures.