John Perceval: an Ethical Representation of a Delinquent Angel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memories of the Origins of Ethnographic Film / Beate Engelbrecht (Ed.)

Contents Preface Beate Engelbrecht IX Introduction 1 The Early Years of Visual Anthropology Paul Hockings 3 The Prehistory of Ethnographic Film Luc de Heusch 15 Precursors in the Documentary Film 23 Robert Flaherty as I Knew Him. R ichard L eacock 2 5 Richard Leacock and the Origins of Direct Cinema: Re-assessing the Idea of an 'Uncontrolled Cinema' Chris tof Decker 31 Grierson Versus Ethnographic Film Brian Winston 49 Research and Record-Making Approaches 57 Recording Social Interaction: Margaret Mead and Gregory Batcson's Contribution to Visual Anthropology in Ethnographic Context Gerald Sullivan 59 From Bushmen to Ju/'Hoansi: A Personal Reflection on the Early Films of John Marshall. Patsy Asch 71 Life By Myth: The Development of Ethnographic Filming in the Work of John Marshall John Bishop 87 Pulling Focus: Timothy Asch Between Filmmaking and Pedagogy Sarah Elder 95 VI Contents Observational and Participatory Approaches 121 Colin Young, Ethnographic Film and the Film Culture of the 1960s David MacDougall 1 23 Colin Young and Running Around With a Camera Judith MacDougall 133 The Origins of Observational Cinema: Conversations with Colin Young Paul Henley 139 Looking for an Indigenous View 163 The Worth/Adair Navajo Experiment - Unanticipated Results and Reactions Richard Chalfen 165 The Legacy of John Collier, Jr. Peter Biella 111 George Stoney: The Johnny Appelseed of Documentary Dorothy Todd Henaut 189 The American Way 205 "Let Me Tell You A Story": Edmund Carpenter as Forerunner in the Anthropology of Visual Media Harald Prins and John Bishop 207 Asen Balikci Films Nanook Paul Hockings 247 Robert Gardner: The Early Years Karl G. -

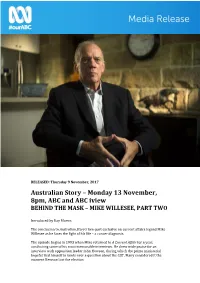

Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO

RELEASED: Thursday 9 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO Introduced by Ray Martin. The conclusion to Australian Story’s two-part exclusive on current affairs legend Mike Willesee as he faces the fight of his life – a cancer diagnosis. The episode begins in 1993 when Mike returned to A Current Affair for a year, conducting some of his most memorable interviews. He drew wide praise for an interview with opposition leader John Hewson, during which the prime ministerial hopeful tied himself in knots over a question about the GST. Many considered it the moment Hewson lost the election. Four weeks later praise turned to condemnation when Mike interviewed two young children held captive by killers during the Cangai siege. “I think this is a classic case where we misjudged the audience reaction,” admits former Nine news chief Peter Meakin. Tiring of nightly current affairs, Mike turned his attention to a variety of business interests and documentary making. While in Kenya on his way to film in Sudan he had a premonition that the small plane he was boarding would crash. Shortly after take-off, it did. Although Mike was unhurt, the experience had a profound impact on him and led him on a long journey back to the Catholic faith of his childhood. In the years since he has invested much of his time into trying to find scientific proof for various religious miracles. It is Mike’s strong religious faith, along with the support of his family, that has helped him since being diagnosed with cancer in October last year. -

Antropología

Artes y Humanidades Guías para una docencia universitaria con perspectiva de género Antropología Jordi Roca Girona ESTA COLECCIÓN DE GUÍAS HA SIDO IMPULSADA POR EL GRUPO DE TRABAJO DE IGUALDAD DE GÉNERO DE LA RED VIVES DE UNIVERSIDADES Elena Villatoro Boan, presidenta de la Comisión de Igualdad y Conciliación de Vida Laboral y Familiar, Universitat Abat Oliba CEU. M. José Rodríguez Jaume, vicerrectora de Responsabilidad Social, Inclusión e Igualdad, Universitat d’Alacant. Cristina Yáñez de Aldecoa, coordinadora del Rectorado en Internacionalización y Relaciones Institucionales, Universitat d’Andorra. Maria Prats Ferret, directora del Observatorio para la Igualdad, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. M. Pilar Rivas Vallejo, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat de Barcelona. Ruth María Abril Stoffels, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat CEU Cardenal Herrera. Anna Maria Pla Boix, delegada del rector para la Igualdad de Género, Universitat de Girona. Esperanza Bosch Fiol, directora de la Oficina para la Igualdad de Oportunidades entre Mujeres y Hombres, Universitat de las Illes Balears. Consuelo León Llorente, directora del Observatorio de Políticas Familiares, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. Mercedes Alcañiz Moscardó, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat Jaume I. Anna Romero Burillo, directora del Centro Dolors Piera de Igualdad de Oportunidades y Promoción de las Mujeres, Universitat de Lleida. María José Alarcón García, directora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat Miguel Hernández d’Elx. Maria Olivella Quintana, coordinadora de la Unidad de Igualdad, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. Dominique Sistach, responsable de la Comisión de Igualdad de Oportunidades, Universitat de Perpinyà Via Domitia. Silvia Gómez Castán, técnica de Igualdad del Gabinete de Innovación y Comunidad, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. -

OCR Document

YUKULTJI NAPANGATI Sprache: Pintupi Region: Kiwirrkura, Northern Territory Geboren: ca. 1970 © Papunya Tula Artists Yukultji Napangati kam 1984 nach Kiwirrkura. Davor lebte sie mit acht ihrer engsten Angehörigen in dem Gebiet westlich von Lake Mackay. Man nimmt an, dass Yukultji, als sie mit ihrer Familie nach Kiwirrkura kam, 14 Jahre alt war. Im Jahre 1999 beteiligte sich Yukultji an dem gemeinschaftlichen Gemälde der Frauen von Kiwirrkura, das im Rahmen des „Western Desert Dialysis Appeal“ (Dialyse Aufruf der Western Desert Region) entstand. Sie wurde 2005 ausgewählt, als eine von neun Künstlern und Künstlerinnen auf der angesehenen Primavera Show im Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney auszustellen. Dies ist eine begehrte Ausstellung für junge australische Künstler unter 35 Jahren. Im September 2009 reiste Yukulti gemeinsam mit der Künstlerin Doreen Reid Nakamarra nach New York, um die Ausstellung „Nganana Tjungurringanyi Tjukurrpa Nintintjakitja – We are here sharing our Dreaming“ in der 80 Washington Square East Gallery zu besuchen. 2015 wurde sie eingeladen, bei der 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in der Queensland Gallery of Modern Art auszustellen. AUSZEICHNUNGEN 2009 Finalist 26th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museums & Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, Darwin, Northern Territory 2010 Finalist 27th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museums & Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, Darwin, Northern Territory 2011 Finalist 28th Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Museums & Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, Darwin, Northern Territory 2011 Finalist Wynne Prize – Highly Commended, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2012 The Alice Springs Art Prize – 1. -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

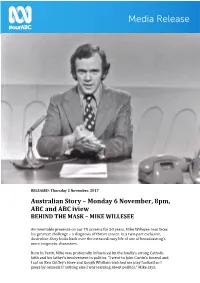

Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE

RELEASED: Thursday 2 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE An inimitable presence on our TV screens for 50 years, Mike Willesee now faces his greatest challenge – a diagnosis of throat cancer. In a two-part exclusive, Australian Story looks back over the extraordinary life of one of broadcasting’s more enigmatic characters. Born in Perth, Mike was profoundly influenced by the family’s strong Catholic faith and his father’s involvement in politics. “I went to John Curtin’s funeral and I sat on Ben Chifley’s knee and Gough Whitlam watched me play football so I guess by osmosis if nothing else I was learning about politics,” Mike says. As a 10-year-old, Mike was sent briefly to the notorious Bindoon Boy’s Town by his father in order to toughen him up. It was a brutal experience. “I still don't know why my father thought I needed to toughen up,” Mike says, “but I did toughen up. You know, it changed me.” Later, a split within the Labor party saw the family ostracised by the Catholic church. His father was railed against from the pulpit and Mike was forced out of school a year early by the Catholic brothers who taught him. These events, and an emerging interest in girls, saw Mike turn his back on the church. After school, Mike fell into journalism, working for papers in Perth and Melbourne before ending up in Canberra. When the ABC launched the ground- breaking current affairs program This Day Tonight, he found himself in the right place at the right time. -

Affairs of the Art Inside Heide, the Creative Crucible That Transformed Australia’S Cultural Landscape

Weekend Australian Saturday 9/04/2016 Page: 1 Section: Review Region: Australia, AU Circulation: 225206 Type: National Size: 2,416.00 sq.cms. press clip APRIL 9-10 2016 Affairs of the art Inside Heide, the creative crucible that transformed Australia’s cultural landscape DESTINATION EUROPE WINE DINING GLORIA STEINEM TOP CHATEAUS, BEST MAX ALLEN ON THE FEMINISM, POLITICS AND VILLAGES, SUPER DEALS NEW BREED OF BAR A LIFE ON THE ROAD TRAVEL & INDULGENCE LIFE REVIEW V1 - AUSE01Z01AR Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) licenced copy Page 1 of 6 AUS: 1300 1 SLICE NZ: 0800 1 SLICE [email protected] Ref: 573001374 Weekend Australian Saturday 9/04/2016 Page: 1 Section: Review Region: Australia, AU Circulation: 225206 Type: National Size: 2,416.00 sq.cms. press clip THE ROARING 40S support and collect. After the Angry Penguins Art historian Richard Haese, whose 1981 study of Heide was seminal in establishing their put down their fertile intellectual and personal relationships in the public imagination — his book’s title, Rebels and roots in staid, stolid Precursors, was taken from a 1962 Heide group exhibition of the same name at the National Melbourne, the art world Gallery of Victoria — says their influence has been profound. “They’re immensely import- in Australia would never ant,” he says. “The Angry Penguin artists have retained a central position in Australian art and be quite the same again, our perception of Australian art is based on these artists. it FionaFi G rub er Haese points out how their work forms part writes of a broader grouping: “Alongside the artists you have the supporters and champions, writ- ow you experience Heide depends ers, poets and jazz musicians.” There have been on where you park. -

Transported Roger Law Stephen Bird

TRANSPORTED ROGER LAW STEPHEN BIRD 30 November – 23 December 2016 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZ Telephone 0131 558 1200 Email [email protected] www.scottish-gallery.co.uk Left: Fogg Dam Tapestry (detail), from an original watercolour, Early Morning - Fogg Dam, Roger Law (cat. 2) Front cover: Roger Law working at the Big Pot Factory, Jingdezhen, China. Photo: Derek Au Roger Law Toby, 2012 Self Portrait, 2012 Stephen Bird Stephen Bird clay, pigment, glaze, H35 x W18 x D24 cms clay, pigment, glaze, H36 x W16 x D20 cms 2 FOREWORD The exhibition quickly evolved as a two-hander with his Roger Law approached The friend Stephen Bird. The two had met in Sydney and Gallery in early 2014 with an idea Law wrote the introduction to Bird’s 2013 Edinburgh International Festival show with The Gallery My Dad was for an exhibition which centred Born on the Moon. Bird was born in The Potteries, trained at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee and making his around cultural transportation, home and a huge international reputation from Sydney he stemming from his own remains aloof from any artist pigeon-hole. Law’s subject is far from the historical-political world from which Bird experience of living and working extracts his concepts; he looks rather to nature (his subjects are delightful caricatures of the evolutionary process) in Australia and his various while his design emphasis is on the decorative. In common, journeys to China, where he both artists are essentially subversive with little interest in convention; both are master craftsmen and both have frequently works and from where completed residencies in China this year, acutely aware of the complex, vital history of their chosen medium between his ceramics return to Europe to China and the West. -

Albert Tucker Born: 29 December 1914 Melbourne, Victoria Died: 23 October 1999 Melbourne, Victoria

HEIDE EDUCATION RESOURCE Albert Tucker Born: 29 December 1914 Melbourne, Victoria Died: 23 October 1999 Melbourne, Victoria Albert Tucker on the roof of the Chelsea Hotel, New York, 1967 Photograph: Richard Crichton This Education Resource has been produced by Heide Museum of Modern Art to provide information to support education institution visits to Heide Museum of Modern Art and as such is intended for their use only. Reproduction and communication is permitted for educational purposes only. No part of this education resource may be stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means. For personal use only – do not store, copy or distribute Page 1 of 20 HEIDE EDUCATION RESOURCE Albert Tucker is known as one of Australia’s foremost artists and as a key figure in the development of Australian modernism in Melbourne. Primarily a figurative painter, his works responded to the world around him and his own life experiences, and they often reflected critically on society. During his career he played an active role in art politics, particularly in the 1940s, writing influential articles about the direction of art in Australia. He also held prominent positions within the art community, including President of the Contemporary Art Society in the late 1940s and again in the 1960s. Tucker grew up during the Depression and began his career as a young artist in the late 1930s, in the years leading up to the outbreak of World War II. At this time, his world was defined by financial insecurity, social inequality and war, and these concerns became the catalyst for much of his painting. -

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2Pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Tional in Fi Le Only - Over Art Fi Le

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia tional in fi le only - over art fi le 5 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 6 7 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 1 2 Bonhams Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Bonhams Viewing Specialist Enquiries Viewing & Sale 76 Paddington Street London Mark Fraser, Chairman Day Enquiries Paddington NSW 2021 Bonhams +61 (0) 430 098 802 mob +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 101 New Bond Street [email protected] +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax Thursday 14 February 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] Friday 15 February 9am to 4.30pm Greer Adams, Specialist in Press Enquiries www.bonhams.com/sydney Monday 18 February 9am to 4.30pm Charge, Aboriginal Art Gabriella Coslovich Tuesday 19 February 9am to 4.30pm +61 (0) 414 873 597 mob +61 (0) 425 838 283 Sale Number 21162 [email protected] New York Online bidding will be available Catalogue cost $45 Bonhams Francesca Cavazzini, Specialist for the auction. For futher 580 Madison Avenue in Charge, Aboriginal Art information please visit: Postage Saturday 2 March 12pm to 5pm +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob www.bonhams.com Australia: $16 Sunday 3 March 12pm to 5pm [email protected] New Zealand: $43 Monday 4 March 10am to 5pm All bidders should make Asia/Middle East/USA: $53 Tuesday 5 March 10am to 5pm Tim Klingender, themselves aware of the Rest of World: $78 Wednesday 6 March 10am to 5pm Senior Consultant important information on the +61 (0) 413 202 434 mob following pages relating Illustrations Melbourne [email protected] to bidding, payment, collection fortyfive downstairs Front cover: Lot 21 (detail) and storage of any purchases. -

Etnografija I Etnografski Film

Etnografija i etnografski film Mirković, Maja Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Pula / Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:137:535260 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-29 Repository / Repozitorij: Digital Repository Juraj Dobrila University of Pula Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Odjel za interdisciplinarne, talijanske i kulturološke studije MAJA MIRKOVIĆ ETNOGRAFIJA I ETNOGRAFSKI FILM Diplomski rad Pula, 2017. Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Odjel za interdisciplinarne, talijanske i kulturološke studije MAJA MIRKOVIĆ ETNOGRAFIJA I ETNOGRAFSKI FILM Diplomski rad JMBAG: 39- KT-D, redovita studentica Studijski smjer: Kultura i turizam Predmet: Etnografija industrije Znanstveno područje: Humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: Etnologija i antropologija Znanstvena grana: Etnologija Mentor: doc. dr. Andrea Matošević Pula, ožujak 2017. IZJAVA O AKADEMSKOJ ČESTITOSTI Ja, dolje potpisani Maja Mirković, kandidat za magistra Kulture i turizma ovime izjavljujem da je ovaj Diplomski rad rezultat isključivo mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na objavljenu literaturu kao što to pokazuju korištene bilješke i bibliografija. Izjavljujem da niti jedan dio Diplomskog rada nije napisan na nedozvoljen način, odnosno da je prepisan iz kojega necitiranog rada, te da ikoji dio rada krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem, također, -

JOSEPH HENRY PERRY When the Murrumbeena Studio Was Not Appropriate, Despite It Being a Rain Perry Simply Upped His Crew and Went on Location

Perry’s skills as a publicist and technician led him to Perry’s Legacy setting up and operating the famous Limelight Department of the Salvation Army in Melbourne. This n the March 2006 edition, the lead article was was the film production unit that played the leading Ititled OUR BIRTHING SUITE . It detailed a visit by role in the pioneering and development of the the editor to the birth place of the Australian moving Australian film industry from 1894 to 1909. The film image industries – the headquarters of the Salvation sequences of SOLDIERS OF THE CROSS was the Army’s Limelight unit in Bourke St. Melbourne. The first use of moving-pictures for a feature-length visit was facilitated by the Salvo’s Territorial Archivist narrative drama in Australia, and possibly the world. and AMMPT Member, Lindsay Cox and proved to be a very moving experience for the visitor as he The Salvation Army’s Murrumbeena Girls home had entered rooms which were virtually untouched since been transformed into a 14-acre studio, where the they were used in the production of some of the Roman Colosseum was photographed on painted world’s earliest feature films such as the Australian backdrops hung on the adjoining tennis courts. Major icon SOLDIERS OF THE CROSS . The following article Perry’s production and art departments produced is from Adelaide based AMMPT Member Michael written scripts, a range of highly detailed and Wollenberg , great grandson of an industry pioneer. elaborate sets and an extensive range of impressive period costumes and props. Smaller sets were Re-discovering the film legacy of purposely built on the roof of Salvation Army Headquarters at 69 Bourke Street, and today, is Australian cinema pioneer, probably the world’s oldest surviving film studio in the Southern Hemisphere, if not the world.