In 1997 UNESCO Included in Its Memory of the World Register an Archive Best Known As the Bleek Collection and Described Thusly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 12 Visual Culture Studies Summaries

GRADE 12 VISUAL CULTURE STUDIES SUMMARIES 1 Artists discussed QUESTION 1 Emerging artists of South Gerard Sekoto, The song of the Pick Africa Gerard Sekoto, Prison Yard George Pemba, Portrait of a young Xhosa woman George Pemba, Eviction – Woman and Child QUESTION 2 South African artists Irma Stern, Pondo Woman influenced by African and/or Irma Stern, The Hunt indigenous art forms Walter Battiss, Fishermen Drawing Nets Walter Battiss, Symbols of Life QUESTION 3 Socio-political – including Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys Resistance art of the ’70s and Jane Alexander, Bom Boys ’80s Manfred Zylla, Bullets and Sweets Manfred Zylla, Death Trap QUESTION 4 Art, craft and spiritual works John Muafangejo. Judas Iscariot betrayed our Lord Jesus for R3.00 mainly from rural South Africa John Muafangejo. New archbishop Desmond Tutu Enthroned Jackson Hlungwani. Large Crucifix and star Jackson Hlungwani, Leaping Fish QUESTION 5 Multimedia and New media – William Kentridge, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris alternative contemporary and William Kentridge. Shadow Procession popular art forms in South Van der Merwe, Biegbak/Confessional Africa Jan van der Merwe, Waiting QUESTION 6 Post-1994 democratic identity Churchill Madikida, Struggles of the heart in South Africa Churchill Madikida,Status Hasan and Husain Essop, Thornton Road Hasan and Husain Essop, Pit Bull Training QUESTION 7 Gender issues Penelope Siopis, Patience on a monument (Choose two artists) Penelope Siopis, Shame Mary Sibande, ‘They don’t make them like they used to do’ Mary Sibande, Conversation with Madame C.J. Walker Lisa Brice, Sex Show Works Lisa Brice, Plastic makes perfect Jane Alexander, Stripped (“Oh Yes” Girl) QUESTION 8 Architecture in South Africa Not included in these summaries. -

Développement De La Linguistique Bantu

Développement de la PREAMBULE Plan linguistique bantu Figures, approches, repr ésentations G. Philippson , L. van der Veen Séminaire linguistique bantu 2 Introduction Sources, premières références Emergence et développements INTRODUCTION Premiers travaux Sources, premières références De 1860 à 1940 De 1940 à nos jours Classification Représentations Conclusion Bibliographie Séminaire linguistique bantu 3 Séminaire linguistique bantu 4 1 Introduction Introduction • Sélection de publications sur l’histoire de la linguistique bantu : • Premières références – Doke & Cole (1961) – L’hiéroglyphe égyptien punt ?? (2500 av. J.-C.) – Bastin (1978), Guarisma (1978), Leroy & Voorhoeve (1978) • Anachronisme… – Vansina (1979, 1980) – Sources arabes à partir de 902 : attestations de mots recueillis le – Flight (1980, 1988) long du littoral oriental – Alexandre (1959, 1968) – Andrea Corsali , navigateur italien (1487-?) : « même langue – Chrétien (1985) parlée du Cap de Bonne Espérance jusqu’à la mer Rouge » – Williamson & Blench (2000) – Ecrits portugais à partir du 16 ème siècle : toponymes, anthro- – Blench (2006) ponymes (côtes ouest et, surtout, est) Séminaire linguistique bantu 5 Séminaire linguistique bantu 6 Introduction – Ecrit du mathématicien italien Antonio Pigafetta (à partir de données rapportées par Lopez en 1588) : un grand nombre de EMERGENCE ET DEVELOPPEMENTS mots de la côte ouest (langue : kongo) Figures, approches – Ouvrages des Anglais Battel (début 17 ème ) et Herbert (1677) Intérêt historique réel, mais pas de véritables études -

Title: the Diamond Smugglers by Ian Fleming 1957

Title: The Diamond Smugglers by Ian Fleming 1957 Published by Jonathan Cape, London Shelf Number: SBV3 823.914 FLEM The Diamond Smugglers is non-fiction work that was first published between 1957 and 1958. It is about the interview that the author undertook with John Collard who was a member of the International Diamond Security Organization (IDSO), which was headed by Sir Percy Sillitoe. Collard narrates how he was recruited into the organization. The book goes on to discuss all activities of the IDSO from 1954 until the operation was closed in 1957. Collard explained that the IDSO was created after an Interpol report had stated that £10 million of diamonds were being smuggled out of South Africa as well as additional amounts from Sierra Leone, Portuguese West Africa, the Gold Coast and Tanganyika. When the drafts of the book were shown to De Beers they objected to several chapters and threatened a sanction against Fleming and The Sunday Times, which resulted in most material being removed. 1 Title: Bushman Paintings by Helen Tongue 1909 Published by Oxford at the Clarendon Press Shelf Number: SBV3 759.968 TONG In many parts of the Cape Colony, where there are caves and rocks, the bushmen have left paintings displaying their artistic skills. These paintings represent leopards; antelopes; lions and other animals that roamed over South Africa. The Bushmen Paintings was written by Helen Tongue and is about the lives of the Bushmen. The book is divided into two parts, the first part being descriptions of all the paintings that are included in the manuscript, the second part encompasses a brief history about the origin of Bushmen as well as where how they lived their lives. -

Fictional Worlds and Characters in Art-Making: Fook Island As Exemplar for Art Practice

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). Fictional worlds and characters in art-making: Fook Island as exemplar for art practice by Allen Walter Laing Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Technologiae: Fine Art In the Department of Visual Art Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture University of Johannesburg 8 October 2018 Supervisor: David Paton Co-supervisor: Prof. Brenda Schmahmann The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Declaration I hereby declare that the dissertation, which I herewith submit for the research qualification Master of Technology: Fine Art to the University of Johannesburg is, apart from recognised assistance, my own work and has not previously been submitted by me to another institution to obtain a research diploma or degree. -

UNISA LIBRARY MANUSCRIPTS COLLECTION John Wickens' Scrapbook of Walter Battiss Materials C1912; 1947-1994

MSS ACC 140 UNISA LIBRARY MANUSCRIPTS COLLECTION John Wickens’ Scrapbook of Walter Battiss materials C1912; 1947-1994 Compiled by Marié Coetzee 2013 Biography of Walter Battiss (1906-1982) Walter Battiss was born on 6 January in Somerset East. The family later moved to Fauresmith in the Orange Free State where Battiss matriculated in 1923. The following year, he started working in the Magistrate of Rustenburg’s Office. He held the first of many solo exhibitions in the Rustenburg Masonic Hall in 1927. Two years later he was transferred to the Supreme Court in Johannesburg. During this period he attended part-time classes at the Art School of the Witwatersrand Technical College. Between 1930 and 1932, Battiss studied full-time at the Johannesburg Teachers’ Training College and the University of the Witwatersrand where obtained a teacher’s diploma. In 1936 Walter Battiss was appointed art master at the Pretoria Boys’ High School and he started seriously studying rock art. In 1938 he travelled to Europe where he met Abbé Breuil, co-founder of the New Group. Battiss married Grace Anderson, a well-known art-educationalist, in 1940 and moved to Giotto’s Hill, Menlo Park, Pretoria, where he stayed until his death in 1982. Battiss was appointed as the first professor and Head of the Department of History of Art and Fine Arts at Unisa in November 1964. His links to the University go back as far as 1935, when he registered for a BA (FA) degree. He obtained this Unisa degree in 1939. In 1965 Battiss launched the pilot issue of De Arte, for many years the only academic art journal in the country. -

Artworks Catalog

ARTWORKS EDITIONED PRINTS ANNA PUGH - 'BONSAI BEACH' 'Bonsai Beach' (1985) by Anna Pugh (1938) Aquatint, Proof Print (Hors de Commerce), Signed 44cm x 33cm (Print Size) 75.5cm x 57cm (Paper Size) Anna Pugh (1938) A prolific and leading English artist, Anna Pugh creates magical and whimsical scenes predominantly of nature, animals, and birds. Limiting the inclusion of people and buildings, Anna’s paintings conjure dreamlike feelings and storytelling. Her use of unusual perspectives, geometry, and graphic design techniques have created an unconventional style which is easily recognisable. Her work can be found in private collections across the United Kingdom, Europe, and North America. SKU: APUG/LE/0001 Price: £450.00 Stock: 1 in stock Prints & Etchings Page: 2 Artworks ANNA PUGH - 'DRAGONFLY' 'Dragonfly' (1985) by Anna Pugh (1938) Aquatint, Proof Print (Hors de Commerce), Signed 44cm x 33cm (Print Size) 75.5cm x 57cm (Paper Size) Anna Pugh (1938) A prolific and leading English artist, Anna Pugh creates magical and whimsical scenes predominantly of nature, animals, and birds. Limiting the inclusion of people and buildings, Anna’s paintings conjure dreamlike feelings and storytelling. Her use of unusual perspectives, geometry, and graphic design techniques have created an unconventional style which is easily recognisable. Her work can be found in private collections across the United Kingdom, Europe, and North America. SKU: APUG/LE/0002 Price: £450.00 Stock: 1 in stock Prints & Etchings Page: 3 Artworks ANNA PUGH - 'NEW YEARS EVE' 'New Years Eve' (1984) by Anna Pugh (1938) Aquatint, Proof Print (Hors de Commerce), Signed 31cm x 27cm (Print Size) 49.5cm x 51cm (Paper Size) Anna Pugh (1938) A prolific and leading English artist, Anna Pugh creates magical and whimsical scenes predominantly of nature, animals, and birds. -

SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY of REGULATION of REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES an Experimental Approach Using a Multi-Agent Based Simulation System

SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY OF REGULATION OF REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES An experimental approach using a multi-agent based simulation system Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät I Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg und Facultat de Lletres i Filosofia Departament de Prehistòria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona von Frau Juana Maria Olives Pons geb. am 04.04.1991 in Maó Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Assumpció Vila Mitja Prof. Dr. Raquel Piqué Huerta Dr. Pablo Cayetano Noriega Blanco Vigil Dr. Jordi Sabater Mir Prof. Dr. François Bertemes Datum der Verteidigung: 18.10.2019 Doctoral thesis __________________ Departament de Prehistòria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Prähistorische Archäologie und Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit von Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY OF REGULATION OF REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES AN EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH USING A MULTI-AGENT BASED SIMULATION SYSTEM Juana Maria Olives Pons Prof. Dr. François Bertemes Prof. Dr. Jordi Estévez Escalera 2019 Table of Contents Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................................................. i Resum .............................................................................................................................................. xi Summary ....................................................................................................................................... -

History of the Arts in the Olympic Games

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the q u alityo f the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission ofof the the copyrightcopyright owner.owner. FurtherFurther reproduction reproduction prohibited prohibited without without permission. -

CHAPTER 1 GEORGE WILLIAM STOW, PIONEER and PRECURSOR of ROCK ART CONSERVATION Today George William Stow Is Remembered Chiefly As

CHAPTER 1 GEORGE WILLIAM STOW, PIONEER AND PRECURSOR OF ROCK ART CONSERVATION One thing is certain, if I am spared I shall use every effort to secure all the paintings in the state that I possibly can, that some record may be kept (imperfect as it must necessarily be .... ). I have never lost an opportunity during that time of rescuing from total obliteration the memory of their wonderful artistic labours, at the same time buoying myself up with the hope that by so doing a foundation might be laid to a work that might ultimately prove to be of considerable importance and value to the student of the earlier races of mankind. George William Stow to Lucy Lloyd, 4 June 1877 Today George William Stow is remembered chiefly as the discoverer of the rich coal deposits that were to lead to the establishment of the flourishing town of Vereeniging in the Vaal area (Mendelsohn 1991:11; 54-55). This achievement has never been questioned. However, his considerable contribution as ethnographer, recorder of rock art and as the precursor of rock art conservation in South Africa, has never been sufficiently acknowledged. In the chapter that follows these achievements are discussed against the backdrop of his geological activities in the Vereeniging area and elsewhere. Inevitably, this chapter also includes a critical assessment of the accusations of fraud levelled against him in recent years. Stow was a gifted historian and ethnographer and during his geological explorations he developed an abiding interest in the history of the indigenous peoples of South 13 Africa and their rich rock art legacy. -

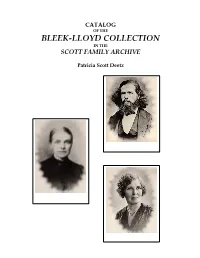

Bleek-Lloyd Collection in the Scott Family Archive

CATALOG OF THE BLEEK-LLOYD COLLECTION IN THE SCOTT FAMILY ARCHIVE Patricia Scott Deetz © 2007 Patricia Scott Deetz Published in 2007 by Deetz Ventures, Inc. 291 Shoal Creek, Williamsburg, VA 23188 United States of America Cover Illustrations Wilhelm Bleek, 1868. Lawrence & Selkirk, 111 Caledon Street, Cape Town. Catalog Item #84. Lucy Lloyd, 1880s. Alexander Bassano, London. Original from the Scott Family Archive sent on loan to the South African Library Special Collection May 21, 1993. Dorothea Bleek, ca. 1929. Navana, 518 Oxford Street, Marble Arch, London W.1. Catalog Item #200. Copies made from the originals by Gerry Walters, Photographer, Rhodes University Library, Grahamstown, Cape 1972. For my Bleek-Lloyd and Bright-Scott-Roos Family, Past & Present & /A!kunta, //Kabbo, ≠Kasin, Dia!kwain, /Han≠kass’o and the other Informants who gave Voice and Identity to their /Xam Kin, making possible the remarkable Bleek-Lloyd Family Legacy of Bushman Research About the Author Patricia (Trish) Scott Deetz, a great-granddaughter of Wilhelm and Jemima Bleek, was born at La Rochelle, Newlands on February 27, 1942. Trish has some treasured memories of Dorothea (Doris) Bleek, her great-aunt. “Aunt D’s” study was always open for Trish to come in and play quietly while Aunt D was focused on her Bushman research. The portraits and photographs of //Kabbo, /Han≠kass’o, Dia!kwain and other Bushman informants, the images of rock paintings and the South African Archaeological Society ‘s logo were as familiar to her as the family portraits. Trish Deetz moved to Williamsburg from Charlottesville, Virginia in 2001 following the death of her husband James Fanto Deetz. -

Patronage, Business and the Value of Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE PATRONAGE, BUSINESS AND THE VALUE OF ART: The Corporate Arts Sponsorship of Absa Bank and Hollard Insurance. Jenni Verschoor A research report submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in History of Art. Johannesburg, 2009 i ABSTRACT This report is a study into the corporate sponsorship of art as is evident in South Africa today. Starting with a history of patronage in the West, it leads to South Africa and the role currently being played by South African companies in the art world. Through an examination of South African patronage by the government and direct interviews with individuals involved in government and corporate sponsorship of the arts, this report endeavours to show how and why organisations such as Absa Bank and Hollard Insurance have chosen to involve themselves in the art world. I will then follow on to discuss the effect that this corporate sponsorship has on the value of art – financially, socially and culturally. The end result will be study on the relationship that exists between the benefactor and the beneficiary of corporate sponsorship in South Africa and the resulting impact this has on the perceived value of art. (art; patronage; value; corporate sponsorship; investment art; corporate collections; Absa; Hollard) ii DECLARATION I declare that this research report is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Masters in History of Art in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. -

Prison and Garden

PRISON AND GARDEN CAPE TOWN, NATURAL HISTORY AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATION HEDLEY TWIDLE PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JANUARY 2010 ii …their talk, their excessive talk about how they love South Africa has consistently been directed towards the land, that is, towards what is least likely to respond to love: mountains and deserts, birds and animals and flowers. J. M. Coetzee, Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech, (1987). iii iv v vi Contents Abstract ix Prologue xi Introduction 1 „This remarkable promontory…‟ Chapter 1 First Lives, First Words 21 Camões, Magical Realism and the Limits of Invention Chapter 2 Writing the Company 51 From Van Riebeeck‟s Daghregister to Sleigh‟s Eilande Chapter 3 Doubling the Cape 79 J. M. Coetzee and the Fictions of Place Chapter 4 „All like and yet unlike the old country’ 113 Kipling in Cape Town, 1891-1908 Chapter 5 Pine Dark Mountain Star 137 Natural Histories and the Loneliness of the Landscape Poet Chapter 6 „The Bushmen’s Letters’ 163 The Afterlives of the Bleek and Lloyd Collection Coda 195 Not yet, not there… Images 207 Acknowledgements 239 Bibliography 241 vii viii Abstract This work considers literary treatments of the colonial encounter at the Cape of Good Hope, adopting a local focus on the Peninsula itself to explore the relationship between specific archives – the records of the Dutch East India Company, travel and natural history writing, the Bleek and Lloyd Collection – and the contemporary fictions and poetries of writers like André Brink, Breyten Breytenbach, Jeremy Cronin, Antjie Krog, Dan Sleigh, Stephen Watson, Zoë Wicomb and, in particular, J.