IR 009 554 Simonson, Michael R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Regional Dialect Lexis in the Names and Occupations of the Gloucestershire Cotswolds: a Reassessment of the Relationship Between Names and Dialects

English regional dialect lexis in the names and occupations of the Gloucestershire Cotswolds: a reassessment of the relationship between names and dialects Item Type Article Authors Parkin, Harry Citation Parkin, H. (2015), ‘English regional dialect lexis in the names and occupations of the Gloucestershire Cotswolds: a reassessment of the relationship between names and dialects’, Dialectologia et Geolinguistica 23, 1, pp. 24–37. DOI 10.1515/dialect-2015-0002 Publisher De Gruyter Journal Dialectologia et Geolinguistica Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 24/09/2021 11:02:04 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/621769 English regional dialect lexis in the names and occupations of the Gloucestershire Cotswolds: A reassessment of the relationship between names and dialects David Harry Parkin Abstract A number of surname-based studies have presented a relationship between medieval regional dialect lexis and the distribution of associated modern-day surnames. However, by carrying out localised research, it appears that the two might not be so closely linked as previously thought, with discrepancies in the distribution of regionally specific names and equivalent occupational descriptions. As a result, there seems to be a need to reconsider the connection between regional lexicons and corresponding name stocks, which may have been less closely related, at a period of non-hereditary by-naming, than current knowledge suggests. 1. Surnames and dialect It has been widely recognised that the regional distribution of certain by-names and surnames,1 from the medieval period up to the present day, can represent regional distinctions in Middle English (ME) dialect lexis and phonology. -

1 Catherine E. Weaver

Catherine E. Weaver Associate Professor, LBJ School of Public Affairs Distinguished Scholar and Research Coordinator, Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law The University of Texas at Austin 2315 Red River Street, SRH 3.358 Austin, Texas 78712 email: [email protected] Strauss Center main phone: (512) 471-6267 Office Phone: (512) 232-3443 Education Ph.D., Political Science May 2003 University of Wisconsin, Madison BA, Political Science and Russian April 1994 University of Michigan Academic Positions Associate Professor, LBJ School of Public Affairs, September 2010 – present University of Texas at Austin Assistant Professor, LBJ School of Public Affairs, January 2009 – August 2010 University of Texas at Austin Assistant Professor of Political Science August 2002 – December 2008 University of Kansas Research Fellow, Brookings Institution August 2001-2002 Washington, D.C. Publications Books: Catherine Weaver. 2008. Hypocrisy Trap: The World Bank and the Poverty of Reform. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ~Co-recipient of the Chadwick Alger Prize for best book on International Organizations and Multilateralism, International Studies Association, 2009. (Co-recipient with Benjamin Schiff) ~Winner of the Society of Policy Scientists 2009 Harold D. Lasswell Prize. Catherine Weaver and Nicola Phillips, eds. 2010. International Political Economy and the Transatlantic Divide. London, UK: Routledge Press. 1 Articles and Book Chapters (* = in peer review journal or reviewed as part of book project): *Catherine Weaver and Susan Park. Forthcoming 2012.“The Anatomy of IO Agency: Anticorruption and Environmental Reform at the World Bank.” In Joel Oestreich, ed. Agency in International Organizations. London: Routledge Press. *Catherine Weaver. 2010. "The Politics of Performance Evaluation: Independent Evaluation at the International Monetary Fund" Review of International Organizations, September 2010, pp.365-385. -

Oregon City High School Commencement the Class of 2020

Oregon City High School 135th Annual Commencement The Class of 2020 Sunday, June 7, 2020 Oregon City High School 12:00pm ~ 4:00pm OCSD Board of Education Evon Tekorius, Chair Martha Spiers, Vice Chair Connie Curteman Scott Dahlman Anna Farmer Steve Soll Pamela White District Administration Larry Didway, Superintendent Kyle Laier, Assistant Superintendent Sara Deboy, Director of Teaching and Learning Susan Dodd, Chief Financial Officer John Ogden, Director of Human Resources Todd Nicholson, Director of Special Services Wes Rogers, Bond Manager OCHS Staff The Class of 2020 Nic Liebrecht Lisa Ramage Doug Thomas Maria Elena Margaret Rierson Trecia Thompson Class Motto Lopez-Mabrey Carlene Roley Adam Thygeson Mike Lord Jake Rondema Caralee Thygeson "Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing." John Lucente Brian Ruby Megan Thyken -Helen Keller Amelia Luna Mina Shalada (Gabi) Rush Stephanie Tolke Jane Lundy Amber Salvey Tiffani Traver Kenrik Lynch Karlie Sanchez Susan Trone Senior Class Officers Eric Lynn Linda Schachtel John Tsugawa Em MacDonald Cynthia Schneider Cathy Varner President Annalies Rimes Jeff Marcoe Patty Scribner Craig Vattiat Vice President Zach Finnegan Karen Markowski Cornelia Seigneur Tricia Vermace Secretary-Treasurer Shaylee Cooper Stephanie Mattox Taddesse Sewore Trevor Vollintine Senior Class Rep. Brittan Bratscher Meagan McBride Mark Sexton Julia Voorhies Brent McClain Christopher Sherrick Brian Walters Royce McCullough Svetlana Shevchenko Marcus Washington Pat McDonald Michael Silva Wally Watson Jenny McKenzie Les Sitton Deby Webb ASB Executive Officers Stacey Mills Clarise Sky-Johnson Patty Westphal Linda Montz Carolyn Smith Kris White President Max Reed Alana Morgan Rocky Smith Carey Wilhelm Vice President Zoe Kleiner Kristin Mull Zella Smith Brenda Williams Secretary-Treasurer Grant Didway Tiffany Mutchler Sue Snow Jessica Williams Aaron Newkirk Clinton Springer Tess Wills Alena Norr Kelly Springer Lisa Wilson Robert Osborn Marty Stinson J.J. -

The Effects of Multimedia and Elaborative Encoding on Learning

The Effects of Multimedia and Elaborative Encoding on Learning Lawrence J. Najjar School of Psychology and Graphics, Visualization, and Usability Laboratory Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332-0170 [email protected] February 7, 1996 (Technical Report GIT-GVU-96-05) Keywords: Multimedia, elaborative encoding, learning Electronic versions of this paper are available via: FTP ftp://ftp.gvu.gatech.edu:/pub/gvu/tech-reports/96-05.ps.Z Gopher gopher://gopher.cc.gatech.edu/pub/gvu/tech-reports World Wide Web http://www.cc.gatech.edu/gvu/reports/TechReports96.html Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................3 Chapter 1 Introduction ..........................................................................4 Chapter 2 Effects of Multimedia on Learning ................................................6 Multimedia Helps People to Learn .....................................................6 Text and Illustrations............................................................ 6 Text and Animated Graphics ...................................................6 Audio and Audio-Visual ........................................................7 Text, Audio, and Illustrations.................................................. 8 Multimedia Does Not Help People to Learn...........................................8 Text and Illustrations............................................................ 9 Text and Animated Graphics ...................................................9 -

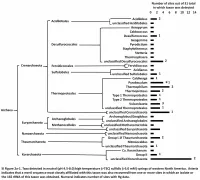

SI Fig 2.Pdf

Figure 2a References Auchtung, T.A., Takacs-Vesbach, C.D. and Cavanaugh, C.A. (2006) 16S rRNA phylogenetic investigation of the candidate division "Korarchaeota". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5077- 5082. Barns, S.M., Delwiche, C.F., Palmer, J.D. and Pace, N.R. (1996) Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences. PNAS (USA) 93, 9188-9193. Barns, S.M., Fundyga, R.E., Jeffries, M.W. and Pace, N.R. (1994) Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot-spring environment. PNAS (USA) 91, 1609-1613. Beam, J.P., Jay, Z.J., Kozubal, M.A. and Inskeep, W.P. (2014) Niche specialization of novel Thaumarchaeota to oxic and hypoxic acidic geothermal springs of Yellowstone National Park. ISME J. 8, 938-951. Connon, S.A., Koski, A.K., Neal, A.L., Wood, S.A. and Magnuson, T.S. (2008) Ecophysiology and geochemistry of microbial arsenic oxidation within a high arsenic, circumneutral hot spring system of the Alvord Desert. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 64, 117-128. Dick, J.M. and Shock, E.L. (2013) A metastable equilibrium model for the relative abundances of microbial phyla in a hot spring. Plos One 8, e72395. Dodsworth, J.A., Blainey, P.C., Murugapiran, S.K., Swingley, W.D., Ross, C.A., Tringe, S.G., Chain, P.S.G., Scholz, M.B., Lo, C.-C., Raymond, J., Quake, S.R. and Hedlund, B.P. (2013) Single-cell and metagenomic analyses indicate a fermentative and saccharolytic lifestyle for members of the OP9 lineage. Nature Comm. 4, 1854 doi: 1810.1038/ncomms2884. Dodsworth, J.A. -

Hunterstown Road Site, ) Westinqhouse Electric Corp

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PRDTECTION AGENCY REGION III In the Matter of: ) Hunterstown Road Site, ) ) Westinqhouse Electric Corporation, ) Spectra-Kote Corporation ) and Frederick M. Shealer ) ) (Respondents) ) ) PROCEEDING UNDER SECTION 106 (a) ) Docket No. II 1-8 7 -9 -DC Or j.n£ uJpieKfHtNbiVK ENVIRONMENTAL ) RESPONSE, COMPENSATION, AND LIABILITY ) ACT OF 1980 AS AMENDED BY THE ) SUPERFUND AMENDMENTS AND ) REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 1986, PUB. L. ) NO. 99-499, 100 STAT. 1613(1986). ) (42 U.S.C. <? 9606(a)) ) Consent Agreement and Order The fol lowing Order, agreed to by the United States Environmental Protection Agency ("EPA"), and Westinghouse Electric Corporation, and Spectra-Kote Corporation, and Frederick M. Shealer ("Respondents"), is issued pursuant to the authority vested in the President of the United States of America by Section 106 (a) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, as amended by the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-499 , 100 Stat. 1613 (1986) ("CERCIA"), 42 U.S.C. § 9606(a), and delegated to the Administrator of the EPA on January 23, 1987 by Executive Order 12580, 52 Federal Register 2923, and further delegated to the Regional Admin is :ra tors of EPA. The actions authorized by this Order are consistent with Section 300.65 of the National Oil and Hazardous Substance Contingency Plan ("NCP"), 40 C.F.R. § 300.65. Notice of the issuance of this Order has been given to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, The Respondents agree to undertake all terms and conditions of this Consent Agreement and Order and not to contest this Consent Agreement and Order. -

Elaborative Encoding, the Ancient Art of Memory, and the Hippocampus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2013) 36, 589–659 provided by RERO DOC Digital Library doi:10.1017/S0140525X12003135 Such stuff as dreams are made on? Elaborative encoding, the ancient art of memory, and the hippocampus Sue Llewellyn Faculty of Humanities, University of Manchester, Manchester M15 6PB, United Kingdom http://www.humanities.manchester.ac.uk [email protected] Abstract: This article argues that rapid eye movement (REM) dreaming is elaborative encoding for episodic memories. Elaborative encoding in REM can, at least partially, be understood through ancient art of memory (AAOM) principles: visualization, bizarre association, organization, narration, embodiment, and location. These principles render recent memories more distinctive through novel and meaningful association with emotionally salient, remote memories. The AAOM optimizes memory performance, suggesting that its principles may predict aspects of how episodic memory is configured in the brain. Integration and segregation are fundamental organizing principles in the cerebral cortex. Episodic memory networks interconnect profusely within the cortex, creating omnidirectional “landmark” junctions. Memories may be integrated at junctions but segregated along connecting network paths that meet at junctions. Episodic junctions may be instantiated during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep after hippocampal associational function during REM dreams. Hippocampal association involves relating, binding, and integrating episodic memories into a mnemonic compositional whole. This often bizarre, composite image has not been present to the senses; it is not “real” because it hyperassociates several memories. During REM sleep, on the phenomenological level, this composite image is experienced as a dream scene. -

By Sophie Alden Weaver, BA a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Resource limitation of autotrophs and heterotrophs in boreal forest headwater streams Item Type Thesis Authors Weaver, Sophie Alden Download date 28/09/2021 05:04:48 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/10913 RESOURCE LIMITATION OF AUTOTROPHS AND HETEROTROPHS IN BOREAL FOREST HEADWATER STREAMS By Sophie Alden Weaver, B.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biology University of Alaska Fairbanks December 2019 APPROVED: Jeremy B. Jones, Committee Chair Mary Beth Leigh, Committee Member Roger W. Ruess, Committee Member Diane Wagner, Chair Department of Biology and Wildlife Kinchal Doerner, Dean College of Natural Science and Mathematics Michael Castellini, Interim Dean of the Graduate School Abstract In stream biofilms, autotrophs and heterotrophs are responsible for the majority of in stream nutrient transformations. In boreal forest catchments, discontinuous permafrost can lead to variation in nutrient and energy resources, which can control competition for nutrients between autotrophs and heterotrophs within these biofilms. I was interested in determining what resources control nutrient utilization by autotrophs and heterotrophs in headwater streams in the boreal forest of interior Alaska. I hypothesized that the outcome of competition between autotrophs and heterotrophs for inorganic nutrients would be dependent on the availability of (i) organic carbon, (ii) light, or (iii) inorganic nutrients. To measure resource limitation and competition at both patch and reach scales, I deployed nutrient diffusing substrata and conducted nutrient uptake experiments in streams along a permafrost gradient at the Caribou-Poker Creeks Research Watershed in interior Alaska. At the patch scale, autotrophs were light and nutrient limited, whereas heterotrophs were carbon and nutrient limited, and at the reach scale, light had the largest influence on nutrient uptake. -

Cognitive and Neuropsychological Aspects of Age-Associated Memory Dysfunction

COGNITIVE AND NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF AGE-ASSOCIATED MEMORY DYSFUNCTION A k a d e m is k a v h a n d l in g som för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen med vederbörligt tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet framlägges för offentlig granskning vid Psykologiska institutionen, Umeå Universitet, Seminarierum 2, fredagen den 24 januari 1992, klockan 10.15 AV Th o m a s K a r l s s o n Psykologiska institutionen, Umeå Universitet, Umeå COGNITIVE AND NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF AGE- ASSOCIATED MEMORY DYSFUNCTION BY Thom as K arlsson Doctoral Dissertation Department of Psychology, University of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden ABSTRACT Memory dysfunction is common in association with the course of normal aging. Memory dysfunction is also obligatory in age-associated neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. However, despite the ubiquitousness of age-related memory decline, several basic questions regarding this entity remain unanswered. The present investigation addressed two such questions: (1) Can individuals suffering from memory dysfunction due to aging and amnesia due to Alzheimer’s disease improve memory performance if contextual support is provided at the time of acquisition of to-be- remembered material or reproduction of to-be-remembered material? (2) Are memory deficits observed in ‘younger’ older adults similar to the deficits observed in ‘older’ elderly subjects, Alzheimer’s disease, and memory dysfunction in younger subjects? The outcome of this investigation suggests an affirmative answer to the first question. Given appropriate support at encoding and retrieval, even densely amnesic patients can improve their memory performance. As to the second question, a more complex pattern emerges. -

R. Kent Weaver's CV

R. KENT WEAVER Professor of Public Policy and Government, Georgetown University Senior Fellow, Governance Studies Program The Brookings Institution McCourt School of Public Policy Georgetown University Old North 37th and O Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20057 Tel: (202) 687-6953 Fax: (202)687-2289 E-Mail: [email protected] PERSONAL DATA Place of Birth: California, USA Citizenship: U.S.A. EDUCATION Ph.D. Harvard University - Political Science - 1982 M.A. Harvard University - Political Science - 1978 B.A. Haverford College - Political Science - 1975 ACADEMIC POSITIONS HELD 9/02 to present Professor of Public Policy and Government, Georgetown University 9/87 to present Senior Fellow, Governance Studies Program, The Brookings Institution 7/83 to 8/87 Research Associate, Governmental Studies Program, The Brookings Institution 9/81 to 6/83 Instructor, Department of Political Science, The Ohio State University 1 ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS HELD 1/04 to 6/06 Associate Dean, Georgetown Public Policy Institute, Georgetown University. 9/00 to 11/02 Co-Director, Welfare Reform and Beyond Initiative, The Brookings Institution VISITING POSITIONS HELD 4/14 to 7/15 Olof Palme Visiting Professor, Department of Political Science, Stockholm University (Funded by the Swedish Research Council) 1/14 to 2/15 Eminent Visiting Professor, Institute of Policy Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam 1/11 to 5/11 and Visiting Fellow, European University Institute, Florence 1/12 to 5/12 2/08 to 5/10 Visiting Professor, Masters of Public Affairs Program, Sciences -

Spring 2020 B-M-S

COMMENCEMENT THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL GRADUATION LIST While every effort is made to ensure accuracy in this commencement program, printing deadlines may result in omission of some names and use of names of persons not completing graduation requirements as intended. This printed program, therefore, should not be used to determine a student’s academic or degree status. The university’s official registry for conferral of degrees is the student’s permanent academic record as reflected on the student’s transcript, maintained by the Office of the University Registrar. Commencement SPRING 2020 Greetings from the President n behalf of the University of Florida, our faculty and our entire university community, I would like to extend my deepest congratulations to you, the Graduates of 2020. OI celebrate your remarkable accomplishment in earning a degree from one of the world’s leading research institutions. I applaud you for the education you have received, for honing your creative, scientific, or analytical skills and for your achievements as students. I join you in thanking your professors, advisors and family and friends for their contributions to your success. This is a time for celebration, but also for reflection on your future. I am confident that the knowledge and experience you gained as a UF student will serve you well regardless of your career or how you choose to invest your life. The university has benefited from your active engagement and contributions to your classes, programs of study and your peers, and we are grateful for your time here. We hope you will recall these years fondly, and that you will remain connected to UF as active members of our distinguished alumni. -

September 2020

E X E C U T I V E C O U N C I L M E E T I N G MINUTES AND REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REGULAR MEETING The regular meeting of the International Executive Council was called to order at 11:00 am, by Chairman Erikson, on Tuesday, September 15, 2020, via audio/video conference call. Other members of the council in attendance were Calabro, Calvey, Burgham, Riley, Furco, Wine, Lavin, and Galbraith. INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT STEPHENSON International President Lonnie R. Stephenson met with the members of the International Executive Council to discuss a variety of matters affecting all branches of the Brotherhood. INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER COOPER International Secretary-Treasurer Kenneth W. Cooper presented financial reports covering the IBEW Pension Fund and the Investment Portfolio of the Brotherhood - both in Canada and in the United States. LEGAL DEFENSE Payments for legal defense, made from the General Fund, were examined and approved in accordance with the requirements of Article X, Section 1, of the IBEW Constitution. FINANCIAL REPORTS The International Secretary-Treasurer's Reports for the various funds of the Brotherhood were presented to the members of the International Executive Council, examined, approved, and filed. APPEALS FILED WITH THE INTERNATIONAL EXECUTIVE COUNCIL The International Executive Council conducted a thorough review of the facts pertaining to an appeal from Local Union 11-member Ivan Bacelic, and it is the decision of the IEC to deny Brother Bacelic’s appeal. ARTICLE XX AND XXI CASES There were no new Article XX or XXI cases during the second quarter of 2019.