Examples from California's Highly Manipulated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

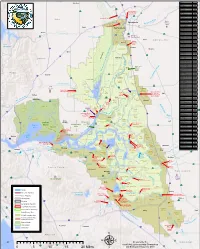

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Comprehensive Operations Plan and Monitoring Special Study Prepared by the Department of Water Resources and the U.S

August 25, 2019 Comprehensive Operations Plan and Monitoring Special Study Prepared by the Department of Water Resources and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation In Accordance with the Water Quality Control Plan for the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento- San Joaquin Delta Estuary—December 12, 2018 This Comprehensive Operations Plan (COP) and Monitoring Special Study (MSS) describes current and potential future actions that fully address the impacts of the State Water Project (SWP) and Central Valley Project (CVP) export operations on water levels and flow conditions that may affect salinity conditions in the southern Delta, including the availability of assimilative capacity for local sources of salinity. The COP includes detailed information regarding the configuration and operations of facilities relied upon in the COP and identifies performance goals for these facilities. Comprehensive Operations Plan Current SWP/CVP Operations Exports The Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) operate the State Water Project and Central Valley Project (collectively Projects), respectively, in compliance with the terms and conditions contained in their water rights permits and licenses issued by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). In December 1999 (and amended in March 2000), the SWRCB issued Water Rights Decision 1641 (D-1641), which amended the associated water rights permits with additional terms and conditions to protect beneficial uses in the Delta. This included assigning responsibility to DWR and Reclamation for meeting specific water quality and flow objectives (DWR, 2006). In addition, DWR and Reclamation must also comply with regulatory requirements, as applicable, contained in, but not limited to: • 2008 U.S. -

San Joaquin River Riparian Habitat Below Friant Dam: Preservation and Restoration1

SAN JOAQUIN RIVER RIPARIAN HABITAT BELOW FRIANT DAM: PRESERVATION AND RESTORATION1 Donn Furman2 Abstract: Riparian habitat along California's San Joa- quin River in the 25 miles between Friant Darn and Free- Table 1 – Riparian wildlife/vegetation way 99 occurs on approximately 6 percent of its his- corridor toric range. It is threatened directly and indirectly by Corridor Corridor increased urban encroachment such as residential hous- Category Acres Percent ing, certain recreational uses, sand and gravel extraction, Water 1,088 14.0 aquiculture, and road construction. The San Joaquin Trees 588 7.0 River Committee was formed in 1985 to advocate preser- Shrubs 400 5.0 Other riparianl 1,844 23.0 vation and restoration of riparian habitat. The Com- Sensitive Biotic2 101 1.5 mittee works with local school districts to facilitate use Agriculture 148 2.0 of riverbottom riparian forest areas for outdoor envi- Recreation 309 4.0 ronmental education. We recently formed a land trust Sand and gravel 606 7.5 called the San Joaquin River Parkway and Conservation Riparian buffer 2,846 36.0 Trust to preserve land through acquisition in fee and ne- Total 7,900 100.0 gotiation of conservation easements. Opportunities for 1 Land supporting riparian-type vegetation. In increasing riverbottom riparian habitat are presented by most cases this land has been mined for sand and gravel, and is comprised of lands from which sand and gravel have been extracted. gravel ponds. 2 Range of a Threatened or Endangered plant or animal species. Study Area The majority of the undisturbed riparian habitat lies between Friant Dam and Highway 41 beyond the city limits of Fresno. -

Salinity Impared Water Bodies and Numerical Limits

Surface Water Bodies Listed as Impaired by Salinity or Electrical Conductivity on the 303(d) List1 Salinity Del Puerto Creek Hospital Creek Ingram Creek Kellogg Creek Knights Landing Ridge Cut Mountain House Creek Newman Wasteway Old River Pit River, South Fork Ramona Lake Salado Creek Sand Creek Spring Creek Tom Paine Slough Tule Canal Electrical Conductivity Delta Waterways (export area) Delta Waterways (northwestern portion) Delta Waterways (southern portion) Delta Waterways (western portion) Grassland Marshes Lower Kings River Mud Slough North Salt Slough San Joaquin River Temple Creek 1 List adopted by the Central Valley Water Board in June 2009. This list has not been approved by the State Water Board or U.S. EPA. Central Valley Water Bodies With Numerical Objectives for Electrical Conductivity or Total Dissolved Solids SURFACE WATERS GROUNDWATER Sacramento River Basin Tulare Lake Basin Hydrographic Units Sacramento River Westside Feather River Kings River American River Tulare Lake and Kaweah River Folsom Lake Tule River and Poso Goose Lake Kern River San Joaquin River Basin San Joaquin River Tulare Lake Basin Kings River Kaweah River Tule River Kern River Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Sacramento River San Joaquin River So. Fork Mokelumne River Old River West Canal All surface waters and groundwaters Delta-Mendota Canal designated as municipal and domestic Montezuma Slough (MUN) water supplies must meet the Chadbourne Slough numerical secondary maximum Cordelia Slough contaminant levels for salinity in Title Goodyear Slough 22 of the California Code of Intakes on Van Sickle and Chipps Regulations. Islands . -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is twofold: to provide general information for anyone interested in the California islands and to serve as a field guide for visitors to the islands. The book covers both general history and nat- ural history, from the geological origins of the islands through their aboriginal inhabitants and their marine and terrestrial biotas. Detailed coverage of the flora and fauna of one island alone would completely fill a book of this size; hence only the most common, most readily observed, and most interesting species are included. The names used for the plants and animals discussed in this book are the most up-to-date ones available, based on the scientific literature and the most recently published guidebooks. Common names are always subject to local variations, and they change constantly. Where two names are in common use, they are both mentioned the first time the organism is discussed. Ironically, in recent years scientific names have changed more recently than common names, and the reader concerned about a possible discrepancy in nomenclature should consult the scientific literature. If a significant nomenclatural change has escaped our notice, we apologize. For plants, our primary reference has been The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, edited by James C. Hickman, including the latest lists of errata. Variation from the nomenclature in that volume is due to more recent interpretations, as explained in the text. Certain abbreviations used throughout the text may not be immedi- ately familiar to the general reader; they are as follows: sp., species (sin- gular); spp., species (plural); n. -

Geology and Ground-Water Features of the Edison-Maricopa Area Kern County, California

Geology and Ground-Water Features of the Edison-Maricopa Area Kern County, California By P. R. WOOD and R. H. DALE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1656 Prepared in cooperation with the California Department of Heater Resources UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library catalog card for tbis publication appears on page following tbe index. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract______________-_______----_-_._________________________ 1 Introduction._________________________________-----_------_-______ 3 The water probiem-________--------------------------------__- 3 Purpose of the investigation.___________________________________ 4 Scope and methods of study.___________________________________ 5 Location and general features of the area_________________________ 6 Previous investigations.________________________________________ 8 Acknowledgments. ____________________________________________ 9 Well-numbering system._______________________________________ 9 Geography ___________________________________________________ 11 Climate.__-________________-____-__------_-----_---_-_-_----_ 11 Physiography_..__________________-__-__-_-_-___-_---_-----_-_- 14 General features_________________________________________ 14 Sierra Nevada___________________________________________ 15 Tehachapi Mountains..---.________________________________ -

9.22 Acre Homesite Off of the San Joaquin River of Sherman Island In

Offering Summary Index • A 9.22 +/- acre homesite off of the San Joaquin River of Sherman Island in Cover .................................................................... 1 Sacramento County, CA • The property presents itself as a great potential for a single-family residence. Offering Summary .......................................2 • Located on the scenic San Joaquin River near Highway 160, North of Antioch. Terms, Rights, & Advisories .................. 3 • Reclamation District No. 341 is in the process of doing levee and road Regional Map .................................................4 enhancements near the property. A letter from the Civil Engineers is on file and available for the Buyers to review at their request. Local Area Map ............................................ 5 Location, Legal Description, & Zoning ........................................................... 6 Property Assesment ................................. 6 Purchase Price & Terms ......................... 6 Soils Map ...........................................................7 Slope Map ........................................................ 8 Assessor Map .................................................9 Photos .............................................................. 10 Page 2 All information contained herein or subsequently provided by Broker has been procured directly from the seller or other third parties and has not been verified by Broker. Though believed to be reliable, it is not guaranteed by seller, broker or their agents. Before entering -

A Century of Delta Salt Water Barriers

A Century of Salt Water Barriers in the Delta By Tim Stroshane Policy Analyst Restore the Delta June 5, 2015 edition Since the late 19th century, California’s basic plan for water resource development has been to export water from the Sacramento River and the Delta to the San Joaquin Valley and southern California. Unfortunately, this basic plan ignores the reality that the Delta is the very definition of an estuary: it is where fresh water from the Central Valley’s rivers meets salt water from tidal flow to the Delta from San Francisco Bay. Productive ecosystems have thrived in the Delta for millenia prior to California statehood. But for nearly a century now, engineers and others have frequently referred to the Delta as posing a “salt menace,” a “salinity problem” with just two solutions: either maintain a predetermined stream flow from the Delta to Suisun Bay to hydraulically wall out the tide, or use physical barriers to separate saline from fresh water into the Delta. While readily admitting that the “salt menace” results from reduced inflows from the Delta’s major tributary rivers, the state of California uses salt water barriers as a technological fix to address the symptoms of the salinity problem, rather than the root causes. Given complex Delta geography, these two main solutions led to many proposals to dam up parts of San Francisco Bay, Carquinez Strait, or the waterway between Chipps Island in eastern Suisun Bay and the City of Antioch, or to use large amounts of water—referred to as “carriage water”— to hold the tide literally at bay. -

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region Karl E

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region Karl E. Longley, ScD, P.E., Chair Linda S. Adams Arnold 11020 Sun Center Drive #200, Rancho Cordova, California 95670-6114 Secretary for Phone (916) 464-3291 • FAX (916) 464-4645 Schwarzenegger Environmental http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/centralvalley Governor Protection 18 August 2008 See attached distribution list DELTA REGIONAL MONITORING PROGRAM STAKEHOLDER PANEL KICKOFF MEETING This is an invitation to participate as a stakeholder in the development and implementation of a critical and important project, the Delta Regional Monitoring Program (Delta RMP), being developed jointly by the State and Regional Boards’ Bay-Delta Team. The Delta RMP stakeholder panel kickoff meeting is scheduled for 30 September 2008 and we respectfully request your attendance at the meeting. The meeting will consist of two sessions (see attached draft agenda). During the first session, Water Board staff will provide an overview of the impetus for the Delta RMP and initial planning efforts. The purpose of the first session is to gain management-level stakeholder input and, if possible, endorsement of and commitment to the Delta RMP planning effort. We request that you and your designee attend the first session together. The second session will be a working meeting for the designees to discuss the details of how to proceed with the planning process. A brief discussion of the purpose and background of the project is provided below. In December 2007 and January 2008 the State Water Board, Central Valley Regional Water Board, and San Francisco Bay Regional Water Board (collectively Water Boards) adopted a joint resolution (2007-0079, R5-2007-0161, and R2-2008-0009, respectively) committing the Water Boards to take several actions to protect beneficial uses in the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Estuary (Bay-Delta). -

C a S E S T U D Y R E P O R T Sherman Island Delta

C A S E S T U D Y R E P O R T SHERMAN ISLAND DELTA PROJECT November 2013 Written by Bradley Angell, Richard Fisher & Ryan Whipple a project of Ante Meridiem Incorporated with the direct support of the Delta Alliance International Foundation © 2013 Ante Meridiem Incorporated ABSTRACT This report is an official beginning to a model design for Sherman Island, an important land mass that lies at the meeting point of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers of the California Delta system. As design is typically dominated by a particular driving discipline or a paramount policy concern, the resulting decision-making apparatus is normally governed by that discipline or policy. After initial review of Sherman Island, such a “single” discipline or “principle” policy approach is not appropriate for Sherman Island. At this critical physical place at the heart of California Delta, an inter-disciplinary and equal-weighted policy balance is necessary to meet both the immediate and long-term requirements for rehabilitation of the project site. Exhibiting the collected work of a small team of design and policy specialists, the Case Study Report for the Sherman Island Delta Project outlines the multitude of interests, disciplines and potential opportunities for design expression on the selected 1,000 acre portion of Sherman Island under review. Funded principally by a generous grant from the Delta Alliance, the team researched applicable uses and technologies with a pragmatic case study approach to the subject, physically documenting exhibitions of each technology as geographically close to the project site as possible. After study and on-site documentation, the team compiled this wealth of discovery in three substantive chapters: a site characterization report, the stakeholders & goals assessment, and a case study report. -

Sherman Island Wetland Restoration Project (Project) Is Composed of Two Phases

Section 5: Project Description 1. Project Objectives: The Sherman Island Wetland Restoration Project (Project) is composed of two phases. The first phase includes constructing a 700 acre wetland restoration area on the west side of the Antioch Bridge and the second phase includes constructing a 1000 acre wetland restoration area on the northeast side of the Antioch Bridge. This Project also incorporates elements of uplands and riparian forest, on the perimeter and on upland areas, including berms and islands. There are no aspects of this project that are required by law or permit condition, thus this project is truly “Additional”. Furthermore, since Sherman Island is significantly subsided, with land elevations between 10 and 25 feet below sea level, all sequestered GHG will be “Permanent”. Subsided Delta islands are like bowls and if tule wetlands are constructed and permanently flooded, these bowls over time will fill up with rhizome root material (or Carbon). And if these lands are flooded permanently, and agricultural activities do not subject the peat material to oxygen or fertilizers, the underlying peat will not continue to emit GHG into the atmosphere and allow subsidence. Some potential risks to “Permanence” would include fire and land management changes that would convert these wetlands back into agricultural fields. However, fire risk is greatly diminished since these projects will be permanently flooded and since DWR owns this property, the likelihood of returning these lands to agriculture is remote. Lastly, the flood risk on Sherman Island is significant but if this were to occur, the carbon sequestered would be under water and essentially capped, with very little GHG release.