Beyond Freefall: Halting Rural Poverty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House & Senate

HOUSE & SENATE COMMITTEES / 63 HOUSE &SENATE COMMITTEES ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PRIVACY AND Meili Faille, Vice-Chair (BQ)......................47 A complete list of all House Standing Andrew Telegdi, Vice-Chair (L)..................44 and Sub-Committees, Standing Joint ETHICS / L’ACCÈS À L’INFORMATION, DE LA PROTECTION DES RENSEIGNEMENTS Omar Alghabra, Member (L).......................38 Committees, and Senate Standing Dave Batters, Member (CON) .....................36 PERSONNELS ET DE L’ÉTHIQUE Committees. Includes the committee Barry Devolin, Member (CON)...................40 clerks, chairs, vice-chairs, and ordinary Richard Rumas, Committee Clerk Raymond Gravel, Member (BQ) .................48 committee members. Phone: 613-992-1240 FAX: 613-995-2106 Nina Grewal, Member (CON) .....................32 House of Commons Committees Tom Wappel, Chair (L)................................45 Jim Karygiannis, Member (L)......................41 Directorate Patrick Martin, Vice-Chair (NDP)...............37 Ed Komarnicki, Member (CON) .................36 Phone: 613-992-3150 David Tilson, Vice-Chair (CON).................44 Bill Siksay, Member (NDP).........................33 Sukh Dhaliwal, Member (L)........................32 FAX: 613-996-1962 Blair Wilson, Member (IND).......................33 Carole Lavallée, Member (BQ) ...................48 Senate Committees and Private Glen Pearson, Member (L) ..........................43 ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE Legislation Branch Scott Reid, Member (CON) .........................43 DEVELOPMENT / ENVIRONNEMENT -

Partie I, Vol. 138, No 12, Éditio Spéciale ( 73Ko)

EXTRA Vol. 138, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 138, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, TUESDAY, JULY 13, 2004 OTTAWA, LE MARDI 13 JUILLET 2004 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members Elected at the 38th General Election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 38e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) West Vancouver—Sunshine Coast John Reynolds West Vancouver—Sunshine Coast John Reynolds Humber—St. Barbe—Baie Verte Gerry Byrne Humber—St. Barbe—Baie Verte Gerry Byrne Whitby—Oshawa Judi Longfield Whitby—Oshawa Judi Longfield Grey—Bruce—Owen Sound Larry Miller Grey—Bruce—Owen Sound Larry Miller Willowdale Jim Peterson Willowdale Jim Peterson Red Deer Bob Mills Red Deer Bob Mills Pickering—Scarborough East Dan McTeague Pickering—Scarborough-Est Dan McTeague Churchill Bev Desjarlais Churchill Bev Desjarlais Avalon R. John Efford Avalon R. John Efford Simcoe—Grey Helena Guergis Simcoe—Grey Helena Guergis Chatham-Kent—Essex Jerry Pickard Chatham-Kent—Essex Jerry Pickard North Nova Bill Casey Nova-Nord Bill Casey Vancouver South Ujjal Dosanjh Vancouver-Sud Ujjal Dosanjh Vancouver Centre Hedy Fry Vancouver-Centre Hedy Fry Newton—North Delta Gurmant Grewal Newton—Delta-Nord Gurmant Grewal Edmonton—Beaumont David Kilgour Edmonton—Beaumont David Kilgour Madawaska—Restigouche Jean-Claude D’Amours Madawaska—Restigouche Jean-Claude D’Amours Bramalea—Gore—Malton Gurbax S. -

Wednesday, February 5, 1997

CANADA 2nd SESSION 35th PARLIAMENT VOLUME 136 NUMBER 67 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, February 5, 1997 THE HONOURABLE GILDAS L. MOLGAT SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates: Victoria Building, Room 407, Tel. 996-0397 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, at $1.75 per copy or $158 per year. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1465 THE SENATE Wednesday, February 5, 1997 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. QUESTION PERIOD Prayers. HERITAGE CUTS TO FUNDING OF CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION—ABROGATION OF ELECTION PROMISE— GOVERNMENT POSITION SENATOR’S STATEMENT Hon. Terry Stratton: Honourable senators, my question is addressed to the Leader of the Government in the Senate. It has to do with CBC funding and the Liberal promises to trash the EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE GST and save the CBC. I am asking this question on behalf of Margaret Atwood, EFFECT OF PROGRAM ON NEW BRUNSWICK Pierre Burton, the Bare Naked Ladies’ Steven Page, singer Sylvia Tyson and other Canadian artists who gathered at the Royal York Hotel on Monday. At that time, Margaret Atwood Hon. Brenda M. Robertson: Honourable senators, over the said: past few weeks many New Brunswickers have approached me about flaws in the new Employment Insurance program. In fact, Your 1993 Red Book promised to protect and stabilize the I have received calls from both workers and employers. Their CBC...We believed you. Was our trust misplaced? message was the same. -

Tuesday, May 2, 2000

CANADA 2nd SESSION • 36th PARLIAMENT • VOLUME 138 • NUMBER 50 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, May 2, 2000 THE HONOURABLE ROSE-MARIE LOSIER-COOL SPEAKER PRO TEMPORE This issue contains the latest listing of Senators, Officers of the Senate, the Ministry, and Senators serving on Standing, Special and Joint Committees. CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1170 THE SENATE Tuesday, May 2, 2000 The Senate met at 2:00 p.m., the Speaker pro tempore in the Last week, Richard Donahoe joined this political pantheon and Chair. there he belongs, now part of the proud political history and tradition of Nova Scotia. He was a greatly gifted and greatly respected public man. He was much beloved, especially by the Prayers. rank and file of the Progressive Conservative Party. Personally, and from my earliest days as a political partisan, I recall his kindness, thoughtfulness and encouragement to me and to others. THE LATE HONOURABLE Dick was an inspiration to several generations of young RICHARD A. DONAHOE, Q.C. Progressive Conservatives in Nova Scotia. • (1410) TRIBUTES The funeral service was, as they say nowadays, quite “upbeat.” Hon. Lowell Murray: Honourable senators, I have the sad It was the mass of the resurrection, the Easter service, really, with duty to record the death, on Tuesday, April 25, of our former great music, including a Celtic harp and the choir from Senator colleague the Honourable Richard A. -

June 15, 2005

Debates - Issue 71 - June 15, 2005 http://www.parl.gc.ca/38/1/parlbus/chambus/senate/deb-e/071db_2005-... Debates of the Senate (Hansard) 1st Session, 38th Parliament, Volume 142, Issue 71 Wednesday, June 15, 2005 The Honourable Daniel Hays, Speaker Visitors in the Gallery SENATORS' STATEMENTS World Blood Donor Day The Honourable Viola Léger, O.C. Tribute on Retirement The Late Scott Young The Late Andy Russell, O.C. ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS The Senate Notice of Motion to Establish New Numbering System for Senate Bills Appropriation Bill No. 2 2005-06 First Reading Banking, Trade and Commerce Notice of Motion to Authorize Committee to Extend Date of Final Report on Study of Issues Dealing with Demographic Change Notice of Motion to Authorize Committee to Extend Date of Final Report on Study of Issues Dealing with Interprovincial Barriers to Trade Notice of Motion to Authorize Committee to Extend Date of Final Report on Study of Consumer Issues Arising in Financial Services Sector The Senate Notice of Motion to Strike Special Committee On Gap Between Regional and Urban Canada State of International Health Services Notice of Inquiry QUESTION PERIOD Information Commissioner Acceptability of Reports Extension of Term National Defence Gagetown—Testing of Agent Orange and Agent Purple House of Commons Ethics Commissioner—Report on Member for York West Ethics Commissioner—Hiring of Law Firms Canada-United States Relations 1 of 34 4/13/2006 2:28 PM Debates - Issue 71 - June 15, 2005 http://www.parl.gc.ca/38/1/parlbus/chambus/senate/deb-e/071db_2005-.. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

Core 1..31 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 38e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 134 No 134 Friday, October 7, 2005 Le vendredi 7 octobre 2005 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Mitchell La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Mitchell (Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food), seconded by Mr. Brison (ministre de l'Agriculture et de l'Agroalimentaire), appuyé par M. (Minister of Public Works and Government Services), — That Bill Brison (ministre des Travaux publics et des Services S-38, An Act respecting the implementation of international trade gouvernementaux), — Que le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant commitments by Canada regarding spirit drinks of foreign la mise en oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris countries, be now read a second time and referred to the par le Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. étrangers, soit maintenant lu une deuxième fois et renvoyé au Comité permanent de l'agriculture et de l'agroalimentaire. The debate continued. Le débat se poursuit. The question was put on the motion and it was agreed to. La motion, mise aux voix, est agréée. Accordingly, Bill S-38, An Act respecting the implementation En conséquence, le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant la mise en of international trade commitments by Canada regarding spirit oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris par le drinks of foreign countries, was read the second time and referred Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays étrangers, est to the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. -

2004-05-12 Pre-Election Spending

Federal Announcements Since April 1, 2004 Date Department Program Amount Time Span Location Recipeint MP Present Tally All Government 6,830,827,550 Per Day 151,796,168 1-Apr-04 Industry TPC 7,200,000 Burnaby, BC Xantrex Technologies Hon. David Anderson 1-Apr-04 Industry TPC 9,500,000 Richmond, BC Sierra Wireless Hon. David Anderson 2-Apr-04 Industry TPC 9,360,000 London, ON Trojona Technologies Pat O'Brien 5-Apr-04 Industry Canada Research Chairs 121,600,000 Calgary, AB Hon. Lucienne Robillard 7-Apr-04 Industry TPC 3,900,000 Drumondville, PQ VisuAide Hon. Lucienne Robillard 7-Apr-04 Industry TPC 5,600,000 Montreal, PQ Fermag Hon. Lucienne Robillard 13-Apr-04 Industry 75,000,000 Quebec, PQ Genome Canada Hon. Lucienne Robillard 26-Apr-04 Industry TPC 3,760,000 Vancouver, BC Offshore Systems Hon. David Anderson 28-Apr-04 Industry TPC 8,700,000 Vancouver, BC Honeywell ASCa Hon. David Anderson 3-May-04 Industry TPC 7,700,000 Ottawa, ON MetroPhotonics Eugene Bellemare 4-May-04 Industry TPC 7,500,000 Port Coquitlam, BC OMNEX Control; Systems Hon. David Anderson 6-May-04 Industry TPC 4,600,000 Kanata, ON Cloakware Corporation Hon. David Pratt 7-May-04 Industry TPC 4,000,000 Waterloo, ON Raytheon Canada Limited Hon. Andrew Telegdi 7-May-04 Industry TPC 6,000,000 Ottawa, ON Edgeware Computer Systems Hon. David Pratt 13-May-04 Industry Bill C-9 170,000,000 Ottawa, ON Hon. Pierre Pettigrew 14-May-04 Industry TPC 4,000,000 Brossard, PQ Adacel Ltd Hon. -

I Equalization and the Offshore Accords of 2005 a Thesis Submitted

Equalization and the Offshore Accords of 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Ashley Metz Copyright Ashley Metz, October 2006, All Rights Reserved i Permission To Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Graduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree the Libraries of the University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work, or in their absence, by the Head of the Department of Political Studies or the Dean of the College of Graduate Studies and Research. It is understood that any copy or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of the material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract The ad hoc Offshore Accords of 2005 have fundamentally altered the landscape of regional redistribution and Equalization in Canada for the foreseeable future. -

Wednesday, April 24, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 032 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 24, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1883 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 24, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [English] _______________ LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA Prayers Mr. Ken Epp (Elk Island, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, voters need accurate information to make wise decisions at election time. With _______________ one vote they are asked to choose their member of Parliament, select the government for the term, indirectly choose the Prime The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now Minister and give their approval to a complete all or nothing list of sing O Canada, which will be led by the hon. member for agenda items. Vancouver East. During an election campaign it is not acceptable to say that the [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] GST will be axed with pledges to resign if it is not, to write in small print that it will be harmonized, but to keep it and hide it once the _____________________________________________ election has been won. It is not acceptable to promise more free votes if all this means is that the status quo of free votes on private members’ bills will be maintained. It is not acceptable to say that STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS MPs will be given more authority to represent their constituents if it means nothing and that MPs will still be whipped into submis- [English] sion by threats and actions of expulsion. -

Thursday, April 26, 2001

CANADA 1st SESSION · 37th PARLIAMENT · VOLUME 139 · NUMBER 29 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, April 26, 2001 THE HONOURABLE DAN HAYS SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 680 THE SENATE Thursday, April 26, 2001 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. ANNIVERSARY OF CHERNOBYL NUCLEAR ACCIDENT Prayers. Hon. A. Raynell Andreychuk: Honourable senators, on this day, April 26, 15 years ago, the Chernobyl accident occurred. Its horrific consequences are still being felt around the world, but more particularly and poignantly in Ukraine. The Chernobyl SENATORS’ STATEMENTS nuclear accident brought disaster to the peoples of Ukraine, Belarus, Russia and other European countries. However, its consequences and the need to rethink nuclear strategy and safety CANADA BOOK DAY with respect to reactors for non-military use are imperative for all countries. In Ukraine alone, Chernobyl took thousands of lives with a painful consequence to many children, causing thyroid Hon. Joyce Fairbairn: Honourable senators, I would not want gland cancer and putting some 70,000 workers into the disabled the week to go by without drawing attention to what is now an category, the consequences of which we are uncertain to this day. annual ritual called Canada Book Day. This day was celebrated Ten thousand hectares of fertile land have been contaminated and on Monday, when we were not sitting. -

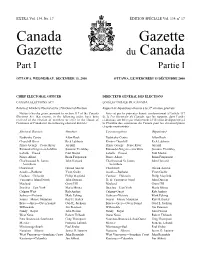

Canada Gazette, Part I, Extra

EXTRA Vol. 134, No. 17 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 134, no 17 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2000 OTTAWA, LE MERCREDI 13 DÉCEMBRE 2000 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members Elected at the 37th General Election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 37e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been delaLoi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Etobicoke Centre Allan Rock Etobicoke-Centre Allan Rock Churchill River Rick Laliberte Rivière Churchill Rick Laliberte Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Assiniboia Assiniboia Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Vancouver Island North John Duncan Île de Vancouver-Nord John Duncan Macleod Grant Hill Macleod Grant Hill Beaches—East York Maria Minna Beaches—East York Maria Minna Calgary West Rob Anders Calgary-Ouest Rob Anders Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Souris—Moose Mountain Roy H.