Horse Country: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Sky Miss (2020)

TesioPower Rancho San Antonio 2020 Sky Miss (2020) Caro Fortino II 4 Siberian Express Chambord 3 Indian Call Warfare 4 In Excess (1987) La Morlaye 13 Saulingo Sing Sing 13 Kantado Saulisa 3-i Vi Vilmorin 7-d Indian Charlie (1995) Dotterel 4-n Sovereign Dancer NORTHERN DANCER 2 Leo Castelli Bold Princess 5 Suspicious Native RAISE A NATIVE 8 Soviet Sojourn (1989) Be Suspicious 4-n Diplomat Way NASHUA 3 Political Parfait Jandy 22-c Peach Butter Creme Dela Creme A4 Uncle Mo (2008) Slipping Round 21-a Roberto Hail To Reason 4-n Kris S Bramalea 12 Sharp Queen PRINCEQUILLO 1 Arch (1995) Bridgework 10-a Danzig NORTHERN DANCER 2 Aurora Pas De Nom 7 Althea Alydar 9 Playa Maya (2000) Courtly Dee A4 NORTHERN DANCER Nearctic 14 Dixieland Band Natalma 2 Mississippi Mud Delta Judge 12 Dixie Slippers (1995) Sand Buggy 4-m CYANE TURN-TO 1 Cyane's Slippers Your Game 16-b Hot Slippers Rollicking 4 Uncle Brennie (2013) Miss Fairfield 8-c Bold Reasoning Boldnesian 4 Seattle Slew Reason To Earn 1-k My Charmer Poker 1 A P Indy (1989) Fair Charmer 13-c Secretariat BOLD RULER 8 Weekend Surprise SOMETHINGROYAL 2 Lassie Dear Buckpasser 1 Malibu Moon (1997) Gay Missile 3-l RAISE A NATIVE NATIVE DANCER 5 MR PROSPECTOR Raise You 8 Gold Digger NASHUA 3 Macoumba (1992) Sequence 13-c Green Dancer Nijinsky II 8 Maximova Green Valley 16-c Baracala Swaps A4 Moon Music (2007) Seximee 2-s RAISE A NATIVE NATIVE DANCER 5 MR PROSPECTOR Raise You 8 Gold Digger NASHUA 3 Smart Strike (1992) Sequence 13-c Smarten CYANE 16 Classy 'n Smart Smartaire A13 No Class Nodouble A1 Strike -

The Formation and Early History of the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben As Shown by Omaha Newspapers

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 11-1-1962 The formation and early history of the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben as shown by Omaha newspapers Arvid E. Nelson University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Nelson, Arvid E., "The formation and early history of the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben as shown by Omaha newspapers" (1962). Student Work. 556. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/556 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r m formation t m im u t m s toot of THE KNIQHTS OF A&~SAR-BBK AS S H O M nr OSAKA NEWSPAPERS A Thaoia Praaentad to the Faculty or tha Dapartmant of History Runic1pal University of Omaha In Partial Fulfilimant of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Art# by Arvld & liaison Ur. November 1^62 UMI Number: EP73194 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73194 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. -

Department 5 DRAFT HORSES

Department 5 DRAFT HORSES Sunday Mon Tue Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday AUGUST 1 2 3 4 Entry Deadline 5 6 7 8 Online 9 10 11 12 deadline 13 14 15 16 17 18 FAIR OPENS 19 20 21 22 23 ARRIVAL 24 2:00 p.m. 25 1:00 p.m. 26 10:00 Youth 6:00 – 10:00 a.m. Halter Classes Quality Hitches Showmanship Riding Classes 7:00 p.m. Log Pulling 3:00 p.m.: Performance Hitches 27 1:00 Gambler’s 28 Choice & Fun Day 8:00 p.m. Release ENTRY: Entries close Aug. 4. Entries must be postmarked by this date. SUPERINTENDENT: Any late entries are subject to double entry fees and prior approval of Rilla Barker Caldwell, Idaho the Superintendent. You may submit your entries online. Online deadline is Aug. 8. Payment JUDGE: must be made with entry. Only Visa and MasterCard accepted online. www.idahofair.com. A $2 per exhibitor convenience fee applies. 1. The Management reserves the right to close entries whenever Because of limited space, livestock and horse trailers can not available space is filled. Ringside Entries are prohibited. be parked inside of the Fairgrounds. To change or add classes for animals already entered, 5. CAMPING: See General Rules and information on page 4 or exhibitor must notify the Premium Office by the evening Website under General Rules. before the show. Entries must be made on forms supplied by 6. ARRIVAL: Draft horses may arrive after 6:00 a.m. the Western Idaho Fair. Entry forms must be completely Wednesday, Aug. -

Saratoga Special Friday, August 11, 2017 Here&There

Year 17 • No. 15 Friday, August 11, 2017 T he aratoga Saratoga’s Daily Racing Newspaper since 2001 Torch Singer Lover’s Key blazes to Statue of Liberty win Tod Marks Tod CANDIP LOOKS TO GET ON TRACK IN TALE OF THE CAT • DAVID DONK STABLE TOUR • ENTRIES/HANDICAPPING 2 THE SARATOGA SPECIAL FRIDAY, AUGUST 11, 2017 here&there... at Saratoga BY THE NUMBERS 2: Cups of Dippin’ Dots left with some picnickers in the backyard by Gary Murray (and kids) before Wednesday’s first race, because No Food in the Paddock. They went back to get them. 7: Golf carts in a gossip scrum on the road by the main track’s three- eighths pole at 8:15 Thursday morning. The mix involved 22 people, several accents and a lot of untrue stories. XXIV: Roman numeral on jock’s agent Angel Cordero Jr.’s hat. LICENSE PLATES OF THE DAY BARN FOX, Virginia. GR8SPA, New York. Thanks to reader Ian Bennett. PICKSIX, Massachusetts. GOT POLO, New York. NAMES OF THE DAY Kristofferson, third race. Maybe he’ll get a push from Glen Campbell (thanks Brooklyn Cowboy). The Intern, seventh race. In honor of The Special’s Madison Scott, who Tod Marks heads off to Australia and the resumption of her Darley Flying Start pro- To lead in a winner at Saratoga, apparently as owner Mike Repole (fourth from gram. Thanks for the hard work. It takes a village. right) brings everybody to the winner’s circle with Driven By Speed after Thursday’s sixth race. Making mischief Street Boss has more Black Tapit.. -

Jenner Visitor Center Sonoma Coast State Beach Docent Manual

CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS Jenner Visitor Center Sonoma Coast State Beach Docent Manual Developed by Stewards of the Coast & Redwoods Russian River District State Park Interpretive Association Jenner Visitor Center Docent Program California State Parks/Russian River District 25381 Steelhead Blvd, PO Box 123, Duncans Mills, CA 95430 (707) 865-2391, (707) 865-2046 (FAX) Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods (Stewards) PO Box 2, Duncans Mills, CA 95430 (707) 869-9177, (707) 869-8252 (FAX) [email protected], www.stewardsofthecoastandredwoods.org Stewards Executive Director Michele Luna Programs Manager Sukey Robb-Wilder State Park VIP Coordinator Mike Wisehart State Park Cooperating Association Liaison Greg Probst Sonoma Coast State Park Staff: Supervising Rangers Damien Jones Jeremy Stinson Supervising Lifeguard Tim Murphy Rangers Ben Vanden Heuvel Lexi Jones Trish Nealy Cover & Design Elements: Chris Lods Funding for this program is provided by the Fisherman’s Festival Allocation Committee, Copyright © 2004 Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods Acknowledgement page updated February 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 1 Part I The California State Park System and Volunteers The California State Park System 4 State Park Rules and Regulations 5 Role and Function of Volunteers in the State Park System 8 Volunteerism Defined 8 Volunteer Standards 9 Interpretive Principles 11 Part II Russian River District State Park Information Quick Reference to Neighboring Parks 13 Sonoma Coast State Beach Information 14 Sonoma Coast Beach Safety 17 Tide Pooling -

Omaha Beach out of Derby with Entrapped Epiglottis

THURSDAY, MAY 2, 2019 WEDNESDAY’S TRACKSIDE DERBY REPORT OMAHA BEACH OUT OF by Steve Sherack DERBY WITH ENTRAPPED LOUISVILLE, KY - With the rising sun making its way through partly cloudy skies, well before the stunning late scratch of likely EPIGLOTTIS favorite Omaha Beach (War Front) rocked the racing world, the backstretch at Churchill Downs was buzzing on a warm and breezy Wednesday morning ahead of this weekend’s 145th GI Kentucky Derby. Two of Bob Baffert’s three Derby-bound ‘TDN Rising Stars’ Roadster (Quality Road) and Improbable (City Zip) were among the first to step foot on the freshly manicured surface during the special 15-minute training window reserved for Derby/Oaks horses at 7:30 a.m. Champion and fellow ‘Rising Star’ Game Winner (Candy Ride {Arg}) galloped during a later Baffert set at 9 a.m. Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Omaha Beach & exercise rider Taylor Cambra Wednesday morning. | Sherackatthetrack CALYX SENSATIONAL IN ROYAL WARM-UP Calyx (GB) (Kingman {GB}) was scintillating in Ascot’s Fox Hill Farms’s Omaha Beach (War Front), the 4-1 favorite for G3 Pavilion S. on Wednesday. Saturday’s GI Kentucky Derby Presented by Woodford Reserve, Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. will be forced to miss the race after it was discovered that he has an entrapped epiglottis. “After training this morning we noticed him cough a few times,” Hall of Fame trainer Richard Mandella said. “It caused us to scope him and we found an entrapped epiglottis. We can’t fix it this week, so we’ll have to have a procedure done in a few days and probably be out of training for three weeks. -

ALL the PRETTY HORSES.Hwp

ALL THE PRETTY HORSES Cormac McCarthy Volume One The Border Trilogy Vintage International• Vintage Books A Division of Random House, Inc. • New York I THE CANDLEFLAME and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. He took off his hat and came slowly forward. The floorboards creaked under his boots. In his black suit he stood in the dark glass where the lilies leaned so palely from their waisted cutglass vase. Along the cold hallway behind him hung the portraits of forebears only dimly known to him all framed in glass and dimly lit above the narrow wainscotting. He looked down at the guttered candlestub. He pressed his thumbprint in the warm wax pooled on the oak veneer. Lastly he looked at the face so caved and drawn among the folds of funeral cloth, the yellowed moustache, the eyelids paper thin. That was not sleeping. That was not sleeping. It was dark outside and cold and no wind. In the distance a calf bawled. He stood with his hat in his hand. You never combed your hair that way in your life, he said. Inside the house there was no sound save the ticking of the mantel clock in the front room. He went out and shut the door. Dark and cold and no wind and a thin gray reef beginning along the eastern rim of the world. He walked out on the prairie and stood holding his hat like some supplicant to the darkness over them all and he stood there for a long time. -

Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., Et Al. Case

Case 15-10952-KJC Doc 712 Filed 08/05/15 Page 1 of 2014 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., et al.1 Case No. 15-10952-CSS Debtor. AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } SCOTT M. EWING, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On July 30, 2015, I caused to be served the: a) Notice of (I) Deadline for Casting Votes to Accept or Reject the Debtors’ Plan of Liquidation, (II) The Hearing to Consider Confirmation of the Combined Plan and Disclosure Statement and (III) Certain Related Matters, (the “Confirmation Hearing Notice”), b) Debtors’ Second Amended and Modified Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Combined Disclosure Statement/Plan”), c) Class 1 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 1 Ballot”), d) Class 4 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 4 Ballot”), e) Class 5 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 5 Ballot”), f) Class 4 Letter from Brown Rudnick LLP, (the “Class 4 Letter”), ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Corinthian Colleges, Inc. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Company Listing Report (Detail)

Page : 1 of 133 02/16/2018 Company Listing Report (Detail) 10:12 AM Event Types: Support Group; Sanctioned Health; Resident Lifestyle Group; Recreation; Permanent Outdoor; Off Site; Media Exceptions Sorted By: Company Name Geographic Area Phone 1 Company Name Full Address Company Type Phone 2 Phone 3 129 Amigos qF @6PM Coconut Cove Linda Maloney 585 Beaulieu Loop (352) 561-4808 The Villages, FL 32162 Resident Lifestyle Group 200 Ladies Club 2W@9AM Burnsed Gail Hole 1011 Pickering Path (352) 633-0980 The Villages, FL 32163 Resident Lifestyle Group 2012 Discussion Group 2&4W@3P Richard Matwyshen 819 Santa Rita (352) 751-0365 Bridgeport Way The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 26'ers West Ladies Lunch 2TH Pat Miller 1728 Augustine Dr (352) 751-7446 @11:30Am El Santiago The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 26er's Club 2ndM Even Mo. @6P La Barbara Lopiccolo 1320 Augustine (352) 633-3780 Hacienda Drive The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 2nd Honeymoon Club 1stM @7:30PM Mitchell Sheinbaum 1304 Iberia (352) 751-4138 Savannah Court The Villages, FL 32162 Resident Lifestyle Group 4 O'Clock Club 1stW@4PM Chula Vista Richard Petulla 518 Chula Vista (352) 750-5641 Ave The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 5 Boroughs Club of NYC 4thF@5:30PM Joseph Herbst 2053 Glenarden (352) 399-5537 Rohan The Villages, FL 32163 Resident Lifestyle Group 5 Streets East 1SA2,5,9,12@6PM Burnsed Patricia Mason 3436 Sassafras Ct (352) 399-6670 The Villages, FL 32163 Resident Lifestyle Group 5-6-7-8Line Dance Prac Impro qW@1PM -

Fasig-Tipton

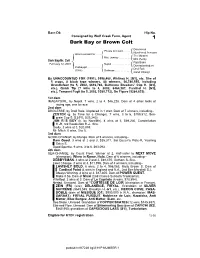

Barn D6 Hip No. Consigned by Wolf Creek Farm, Agent 1 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Damascus Private Account . { Numbered Account Unaccounted For . The Minstrel { Mrs. Jenney . { Mrs. Penny Dark Bay/Br. Colt . Raja Baba February 12, 2001 Nepal . { Dumtadumtadum {Imabaygirl . Droll Role (1988) { Drolesse . { Good Change By UNACCOUNTED FOR (1991), $998,468, Whitney H. [G1], etc. Sire of 5 crops, 8 black type winners, 88 winners, $6,780,555, including Grundlefoot (to 5, 2002, $616,780, Baltimore Breeders’ Cup H. [G3], etc.), Quick Tip (7 wins to 4, 2002, $464,387, Cardinal H. [G3], etc.), Tempest Fugit (to 5, 2002, $380,712), Go Figure ($284,633). 1st dam IMABAYGIRL, by Nepal. 7 wins, 2 to 4, $46,228. Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, one to race. 2nd dam DROLESSE, by Droll Role. Unplaced in 1 start. Dam of 7 winners, including-- ZESTER (g. by Time for a Change). 7 wins, 3 to 6, $199,512, Sea- gram Cup S. [L] (FE, $39,240). JAN R.’S BOY (c. by Norcliffe). 4 wins at 3, $69,230, Constellation H.-R, 3rd Resolution H.-L. Sire. Drolly. 2 wins at 3, $20,098. Mr. Mitch. 6 wins, 3 to 5. 3rd dam GOOD CHANGE, by Mongo. Dam of 5 winners, including-- Ram Good. 3 wins at 2 and 3, $35,317, 3rd Queen’s Plate-R, Yearling Sales S. Good Sparkle. 9 wins, 3 to 6, $63,093. 4th dam SEA-CHANGE, by Count Fleet. Winner at 2. Half-sister to NEXT MOVE (champion), When in Rome, Hula. -

Marin Horse Council Newsletter Summer 2016

2016Marin SUMMER EQUINOX NEWSLETTERHorse Council ISSUEISSUE 125127 Marin Horse Council | 171 Bel Marin Keys Blvd . | Novato, CA 94949 | 415 259. 5783. | www .MarinHorseCouncil .org IN THIS ISSUE FROM THE SADDLE President’s message . 1 OUT ON THE TRAIL My Lucky Life at Golden Gate Fields . 2 Morgan Horse Ranch and . SVMHA . .2 Johnny Walker . 4 Monte Kruger presenting trophy to rider at Southern Marin Horsemen’s Association Junior & Open Horse Show Eaton’s Ranch Horse Drive . 4 From the Saddle Pencil Belly Ranch . 6 Summer is upon us, the horse show season is in full swing and trail riding couldn’t be better . History of SMHA . 8 Flies are in abundance, please take precautions as we really don’t want to see another out- break of Pigeon Fever like many barns experienced last year . It’s not the end of the world but NEWS & UPDATES it can sure slow you down . Mule: Living on the Outside 10 Marin County Parks will be examining and making recommendations for Region 3 and 4 this Summer and Fall through the Parks Road and Trail Management Plan . I’ve written enough SMART Train Letter . 12 about this issue in the past that you all should have a pretty good feel for the process . Region 3 is Indian Valley and Pacheco Open Space while Region 4 is Mt . Burdell, Little Mountain, O’Hair Park and Indian Trees Open Space . Community planning meetings will be held to VET’S CORNER discuss which trails are to remain open, which ones will be slated for closure or which are appropriate for a change of use .