Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Lullaby by Sarah Dessen CHAPTER ONE the Name of The

This Lullaby by Sarah Dessen CHAPTER ONE The name of the song is “This Lullaby.” At this point, I’ve probably heard it, oh, about a million times. Approximately. All my life I’ve been told about how my father wrote it the day I was born. He was on the road somewhere in Texas, already split from my mom. The story goes that he got word of my birth, sat down with his guitar, and just came up with it, right there in a room at a Motel 6. An hour of his time, just a few chords, two verses and a chorus. He’d been writing music all his life, but in the end it would be the only song he was known for. Even in death, my father was a one-hit wonder. Or two, I guess, if you count me. Now, the song was playing overhead as I sat in a plastic chair at the car dealership, in the first week of June. It was warm, everything was blooming, and summer was practically here. Which meant, of course, that it was time for my mother to get married again. This was her fourth time, fifth if you include my father. I chose not to. But they were, in her eyes, married—if being united in the middle of the desert by someone they’d met at a rest stop only moments before counts as married. It does to my mother. But then, she takes on husbands the way other people change their hair color: out of boredom, listlessness, or just feeling that this next one will fix everything, once and for all. -

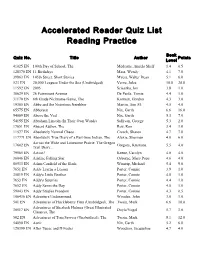

AR Quiz List by Title

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Reading Practice Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 128370 EN 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7.0 39863 EN 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 5.1 6.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 31170 EN 6th Grade Nickname Game, The Korman, Gordon 4.3 3.0 19385 EN Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Martin, Ann M. 4.5 4.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 54089 EN Above the Veil Nix, Garth 5.3 7.0 54155 EN Abraham Lincoln (In Their Own Words) Sullivan, George 5.3 2.0 17651 EN Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 3.4 1.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 117771 EN Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian, The Alexie, Sherman 4.0 6.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary... 79585 EN Action! Keene, Carolyn 4.8 4.0 36046 EN Adaline Falling Star Osborne, Mary Pope 4.6 4.0 86533 EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Winerip, Michael 5.4 9.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 35819 EN Addy's Little Brother Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 59043 EN Addy Studies Freedom Porter, Connie 4.3 0.5 106436 EN Adventure Underground Wooden, John 3.0 1.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Great Illustrated 30517 EN Doyle/Vogel 5.7 3.0 Classics), The 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 54090 EN Aenir Nix, Garth 5.2 6.0 120399 EN After Tupac and D Foster Woodson, Jacqueline 4.7 4.0 353 EN Afternoon of the Elves Lisle, Janet Taylor 5.0 4.0 14651 EN Afternoon on the Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 2.6 1.0 119440 EN Airman Colfer, Eoin 5.8 16.0 5051 EN Alan and Naomi Levoy, Myron 3.3 5.0 19738 EN Alaskan Adventure, The Dixon, Franklin W. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

Clearview Regional High School District Summer Assignment Coversheet 2017

Clearview Regional High School District Summer Assignment Coversheet 2017 Course English III- Advanced and Honors Teacher(s) Ms. Satterfield, Mr. Porter, & Ms. Barry Due Date Monday, September 11, 2017 Grade Category/Weight for Q1 Collected and counts as a Daily Assignment on 9/11. After opportunity for class discussion or questions, counts as a Minor Assessment/Quiz Grade on 9/15 New Jersey Student Learning ● Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support Standards covered analysis of what the text says. ● Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they work together and build on one another. ● By the end of grade 11, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 11-CCR text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range. Description of Assignment 1) Students are to read a book of their choice and analyze the text for the following literary approaches: Gender Studies, Biographical, Historical, Psychoanalytical, Marxist, Formalist, Reader Response 2) Complete graphic organizer at the end of this document 3) Choose the responses from two boxes in the organizer and develop your ideas into a paragraph that analyzes the novel as a whole. Explain why your points are significant to the text and society as a whole. Purpose of Assignment Analyze literature through various critical perspectives Specific Expectations Thoroughly and independently complete graphic organizer with comments that demonstrate analysis. Then develop ideas into a well constructed paragraph to analyze the novel as a whole. -

Advocacy Issue

THE ADVOCACY ISSUE THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE YOUNG ADULT LIBRARY SERVICES ASSOCIATION VOLUME NUMBER 15 03 CYPHER AS YOUTH ADVOCACY SPRING 2017 LIBRARIES AS REFUGE FOR ADVOCATING FOR CREATING A UNIQUE MARGINALIZED YOUTH TEENS IN PUBLIC BRAND FOR YOUR $17.50 » ISSN 1541-4302 LIBRARIES + SCHOOL LIBRARY registration now open! YALSA’SYALSA’SYoungYoung AdultAdult ServicesServices Louisville,Louisville, KYKY •• NovemberNovember 3–5,3–5, 20172017 # YA LS A17 JOIn us as we explore ways to empower teens to increase your library’s impact! The Official Journal of the Young Adult Library Services Association SPRING 2017 VOLUME 15 | NUMBER 3 CONTENTS ISSN 1541-4302 HIGHLIGHT FEATURES 4 25 YALSA’S SELECTED LISTS, 2.0 ADVOCATING FOR TEENS IN PUBLIC LIBRARIES+ 6 » Tiffany Boeglen & Britni Cherrington-Stoddart THE LIBRARY’S ROLE IN PROTECTING TEENS’ PRIVACY: 31 A YALSA POSITION PAPER CREATING A UNIQUE BRAND FOR YOUR SCHOOL LIBRARY 8 » Kelsey Barker ANSWERING THE CALL FOR MIDDLE SCHOOL COLLEGE 36 AND CAREER READINESS: YALSA “FUTURE READY” LIBRARIES AS REFUGE FOR MARGINALIZED YOUTH PROJECT KICKS OFF » Deborah Takahashi » Laura Pitts 40 10 FROM AWARENESS TO ADVOCACY: AN URBAN TEEN REIMAGINED LIBRARY SERVICES FOR AND WITH TEENS LIBRARIAN’S JOURNEY FROM PASSIVITY TO ACTIVISM 11 » David Wang 2017 YALSA BOOK AWARD WINNERS AND SELECTED 43 BOOK AND MEDIA LISTS MAKING A CASE FOR TEENS SERVICES: TRANSFORMING LIBRARIES AND PUBLISHING » Audrey Hopkins EXPLORE 15 RESEARCH ROUNDUP: ADVOCACY: A FOCUS ON PRIVACY PLUS AND SURVEILLANCE » Lucia Cedeira Serantes 2 45 FROM THE EDITOR GUIDELINES FOR AUTHORS » Crystle Martin INDEX TO ADVERTISERS 3 46 TRENDING FROM THE PRESIDENT THE YALSA UPDATE 18 » Sarah Hill USING MEDIA LITERACY TO COMBAT YOUTH EXTREMISM » D.C. -

The Sarah Dessen Book Club Kit

THE SARAH DESSEN BOOK CLUB KIT SPEND YOUR SUMMER WITH SARAH Dear Book Club Coordinator: Here at Penguin Young Readers Group we are calling Summer 2013 The Summer of Sarah. The beloved bestseller Sarah Dessen will be publishing her 11th book this summer, which takes place in one of her fans’ favorite settings, the fi ctional beach town of Colby. Dessen’s latest novel, The Moon and More, will be hitting the shelves this June, and she will be touring in schools and bookstores all across the country to connect with her fans new and old. In anticipation of a local visit, or in lieu of meeting the author in person, we have assembled your Summer of Sarah book club kit to welcome readers in your community into your local book club meetings all summer long. With Penguin's Summer of Sarah book club kit, you can hold discussions about specifi c Dessen titles or more thematic sessions on a variety of topics, such as relationships, moving away, loss and letting go, and change (which everyone can relate to). Since the summer is time for teens to let go of the worries and stress of the school “ year, this book club kit also includes fun quizzes, a recipe from Sarah's favorite summer treats, and playlists handpicked by Sarah herself. Tailor your book club in whatever format best fi ts your participants, and have a fun-fi lled summer… with Sarah! 1 stick margarine Tips for your event: 1.5 graham cracker crumbs 1 small bag chocolate chips 14 oz. -

Improve Your Fluency in English. Read Below. ‘Youth Culture Fluency Enhancement List’-‘Λίστα Νεανικής Κουλτούρας Και Ενίσχυσης Ευφράδειας’

Ενισχύστε την ευφράδεια σας στα Αγγλικά – Improve your fluency in English. Read Below. ‘Youth culture fluency enhancement list’-‘Λίστα νεανικής κουλτούρας και ενίσχυσης ευφράδειας’, Dear parents, This letter has as a goal the improvement of your children’s fluency in the English language. Your child’s ability to deal comfortably with the language depends considerably on what happens in class, but also on what happens outside of class, during fun activities. Fluency reinforcement is vital for your children’s professional, educational and many times social success and it can be achieved with joy. My teachers and I happily put together an amazing ‘Youth culture fluency enhancement list’ which is the perfect tool to assist you in improving your children’s English language skills. The holiday season as well as weekends are the perfect time to pursue this goal. So, why not kill two birds with one stone – have fun and improve your English at the same time! Trust us-our list is full of the coolest TV shows/books/movies of today and it is divided in age groups for your convenience. Υou only need to find the age group that suits you and make a choice! If your child is below the age of fourteen, it is highly suggested that you research each show you allow them to watch. Our list is, of course, age appropriate; however, we understand that everyone raises their children differently, and so, we urge you to confirm that you, as well as your child, are happy with your selection. So, have a look, find something you or your children love and include it in your daily activities! We are looking forward to receiving your feedback either by email or on messenger. -

2017 List of Cream of the Crop for Children's and Young Adult Literature

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Library Documents Maine State Library 4-2017 2017 List of Cream of the Crop for Children’s and Young Adult Literature Maine Regional Library System Book Review Group Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/msl_docs Recommended Citation Maine Regional Library System Book Review Group, "2017 List of Cream of the Crop for Children’s and Young Adult Literature" (2017). Library Documents. 116. http://digitalmaine.com/msl_docs/116 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Documents by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine Regional Library System 28th Annual Reading Round-Up of Children’s and Young Adult Literature Augusta Civic Center April 27, 2017 MAINE EXAMINATION COLLECTION OF CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG ADULT BOOKS Cream of the Crop Total books: 101 KEY L Library binding [GN] Graphic Novel R Reinforced trade binding [M] Maine Author, Illustrator, Setting T Trade binding PICTURE BOOK FICTION [total books in this category: 29] Ashman, Linda. All We Know. HarperCollins. 978-0-06-168958-1,T $17.99 (PreK-Grade 3). In simple, quiet lyrical text, and large, soft Jane Dyer illustrations, that follow the seasons of the year, a mother explains how the love for her child grew - as a sprout grows to a seed, a star shines, the sun rises. This is a lullaby, a love letter for our youngest readers. Bagley, Jessica. Before I Leave. -

Louna Knows a Lot About Weddings— but Not So Much About Love

Louna knows a lot about weddings— but not so much about love. fter many summers working at her mother’s wedding planning business, Louna A has seen every sort of wedding, from informal on the beach to elegant in historic mansions. She’s handled all kinds of crises: AWOL brides, scene-stealing bridesmaids, controlling grooms. And she’s seen the eventual outcome of each perfect wedding. Maybe that’s why she’s deeply cynical about happily-ever-after endings, especially since her own idyllic first love ended sadly. So when happy-go-lucky serial dater Ambrose enters her life, Louna won’t take him seriously. He is sure he can change. Louna is betting that he can’t. But Ambrose hates not getting what he wants, and Louna is the girl he’s been waiting for. SARAH DESSEN has been called the queen of contemporary young adult fiction. She is the author of twelve previous novels, which include the New York Times bestsellers Saint Anything, The Moon and More, What Happened to Goodbye, Along for the Ride, Lock and Key, Just Listen, The Truth About Forever, and This Lullaby. Her first two books,That Summer and Someone Like You, were the basis for the movie How to Deal. She is the recipient of the 2017 Margaret A. Edwards award from the American Library Association, recognizing her significant contribution to young adult literature. Listen to more from Sarah Dessen, available on audio from Listening Library, and visit her online at sarahdessen.com or on Twitter @sarahdessen. KARISSA VACKER received her BFA in theater from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, before performing lead roles at regional theaters across the country. -

Just Listening to Sarah Dessen

Robyn Seglem Just Listening to Sarah Dessen t was the second week of school, reception and at the conference, and I had just brought my copy where she spoke about romance Iof Sarah Dessen’s Just Listen to and YA literature. As expected, my classroom to put on my she was easy to talk to, and shelves. As we waited for first hour shared insights into her career as to begin, Callie, a bright-eyed 7th an author: grader, rushed toward me, explain ing that she had just seen the list of TAR: I first discovered your work recommended books in my class when I was teaching sopho room newsletter and had noticed more English in 2000. When the newest Sarah Dessen title. Did I my librarian recommended have it? Reaching for it on my Dreamland to me, I immedi shelves, I shared with her that I not ately read it and fell in love only had the book, but I would with Caitlin’s story. My have the privilege of interviewing and meeting Sarah students quickly began passing it around, and I’m in Nashville at the ALAN convention. From that not sure it ever went back on the library’s shelves moment, Callie and I shared a bond that went beyond that year. Then, a couple years ago, I switched to the student-teacher bond: it was a bond shared by seventh grade English, and figured I would have to avid readers. discover new authors that would appeal to a August, September, October and, finally, Novem younger audience. -

Here's What Happens in a Realistic Fiction Novel

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ All about Realistic Fiction for Teens By Jennifer Brannen Here's what Realistic Fiction is: Realistic fiction is real life set to fiction. It's about anything that can happen in real life -- good, bad, and in-between. It's real emotions and behaviors in real settings and encompasses the experiences of characters from all different backgrounds. It can also include extremes, both positive and negative, from high living with a focus on wealth, designer clothes, and private schools to the darker extremes of drug use, family breakdowns, and sexual assault. The only limit is reality, which, depending on one's point of view, is either a jump-off point into the fantastical or just where it starts to get interesting all on its own. Here's what happens in a Realistic Fiction novel: Well, almost anything except the fantastical is fair game. Stories are frequently about life changing events and their repercussions or opportunities for growth. It can be as sweet as first love and finding out who you really are ( Into the Wild Nerd Yonder ) or as bleak as coming to terms with a sexual assault ( Speak ). Friendships, love, sex, relationships, cliques, school, growing up, family issues, and leaving for college are all common themes in realistic novels for teens. Often, realistic fiction focuses on solving problems, voyages (sometimes literal ones) of self-discovery, and coming of age. These stories can be played for humor or for drama, but angst and silliness are not necessarily mutually exclusive in the same story. A few things to keep in mind: • Coming of age is a very common theme; the trials and tribulations of growing up take many forms but they comprise a classic and rich theme in YA realistic fiction. -

DREAMLAND by Sarah Dessen a Reader's Companion by Patty Campbell Well-Known Columnist and Lecturer on Young Adult Literature

DREAMLAND by Sarah Dessen A Reader's Companion By Patty Campbell Well-known Columnist and Lecturer on Young Adult Literature Introduction "When he hit me, I didn't see it coming, It was just a quick blur, a flash out of the corner of my eye, and then the side of my face just exploded, burning, as his hands slammed against me." Strange, sleepy Rogerson, with his long brown dreads and brilliant green eyes, had seemed to Caitlin to be an open door. With him she could be anybody, not just the second-rate shadow of her two-years-older sister Cass. But now she is drowning in the vacuum Cass left behind when she turned her back on her family's expectations. Caitlin wanders in a dreamland of drugs and a nightmare of sudden fists, trapped in her search for herself. As violence becomes more and more prevalent in our world, one out of every five teenage girls in America will be beaten by a dating partner, and one third to one half of married women will be victims of abuse. Yet shame, fear, and assumed guilt keeps many in conspiracy of silence about this widespread but invisible anguish. Why do girls allow themselves to get into such relationships—and what keeps them there? In this riveting novel, Sarah Dessen searches for understanding and answers through the mind of a young girl who suddenly finds herself in a trap of constant menace, a trap that is baited with love and need. More and more she must frantically manage her every action to avoid being hit by the hands that had seemed so gentle.