GAO-19-470, NORTHERN BORDER SECURITY: CBP Identified Resource Challenges but Needs Performance Measures to Assess Security Betwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..92 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 148 Ï NUMBER 370 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, December 12, 2018 Speaker: The Honourable Geoff Regan CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 24761 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, December 12, 2018 The House met at 2 p.m. On November 28, I met Patrick Bonvouloir, the president and CEO of IHR Télécom, a company that rolled out fibre optics across my riding. My colleague, the member for Saint-Jean was there, and we discussed what needs to be done to move forward quickly, Prayer including the involvement of the CRTC. I want to point out that IHR Télécom was among the first to Ï (1405) receive federal and provincial government approval. It has done [English] exemplary work, and the first homes in Pike River and Saint- The Speaker: It being Wednesday, we will now have the singing Sébastien will be connected as of January 2019. Everyone involved of O Canada, led by the hon. member for Long Range Mountains. in this file must work together to get all of Brome—Missisquoi connected as quickly as possible. [Members sang the national anthem] I want to take this opportunity to wish everyone happy holidays and to thank my team for their excellent work. STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS *** [Translation] [English] NEW YEAR'S RESOLUTIONS HUMAN RIGHTS Mr. Luc Thériault (Montcalm, BQ): Mr. Speaker, on behalf of Mr. Garnett Genuis (Sherwood Park—Fort Saskatchewan, the Bloc Québécois, I would like to wish all Quebeckers a merry CPC): Mr. Speaker, while we enjoy time away, I hope we will Christmas and a happy new year. -

Race Rocks (Xwayen) Proposed Marine Protected Area Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisher

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) Proposed Marine Protected Area Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report Nicole Backe, Sarah Davies, Kevin Conley, Gabrielle Kosmider, Glen Rasmussen, Hilary Ibey, Kate Ladell Ecosystem Management Branch Pacific Region - Oceans Sector Fisheries and Oceans Canada, South Coast 1965 Island Diesel Way Nanaimo, British Columbia V9S 5W8 Marine Ecosystems and Aquaculture Division Fisheries and Oceans Canada Pacific Biological Station 3190 Hammond Bay Road Nanaimo, British Columbia V9T 6N7 2011 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2949 ii © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs 97-13/2949E ISSN 1488-5387 Correct citation for this publication: Backe, N., S. Davies, K. Conley, G. Kosmider, G. Rasmussen, H. Ibey and K. Ladell. 2011. Race rocks (XwaYeN) proposed marine protected area ecosystem overview and assessment report. Can. Manuscr. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2949: ii + 30 p. Executive Summary Background Race Rocks (XwaYeN), located 17 km southwest of Victoria in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, consists of nine islets, including the large main island, Great Race. Named for its strong tidal currents and rocky reefs, the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are a showcase for Pacific marine life. This marine life is the result of oceanographic conditions supplying the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area with a generous stream of nutrients and high levels of dissolved oxygen. These factors contribute to the creation of an ecosystem of high biodiversity and biological productivity. In 1980, the province of British Columbia, under the authority of the provincial Ecological Reserves Act, established the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. This provided protection of the terrestrial natural and cultural heritage values (nine islets) and of the ocean seabed (to the 20 fathoms/36.6 meter contour line). -

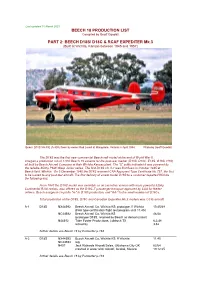

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

3. Strait of Juan De Fuca Ecosystem: Marine Shorelines

Clallam County SMP Update - Inventory and Characterization Report 3. STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA ECOSYSTEM: MARINE SHORELINES Clallam County marine shorelines are buffeted directly by wind and waves entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca from the Pacific Ocean. The shoreline is shaped by seasonal shifts in weather along with cycles of ocean temperature and long term climate change. The underlying geology of the Olympic Peninsula also affects the shape and character of the shoreline through erosion, landslides, sediment movement and beach formation. The protected coves, bays and river mouths along the Strait of Juan de Fuca have been the sites for human settlements for thousands of years. More recently, the weather and spectacular views of wildlife have attracted development along exposed bluffs and beaches. What happens along the marine shoreline—through natural or human-generated activities—affects the people who live along the shorelines as well as resource-based businesses and the many species that depend on the nearshore for food, cover from predators migrating to the ocean. The Strait of Juan de Fuca provides habitat and migration corridors for many species of Puget Sound and Fraser River salmon, marine mammals and thousands of migratory birds, including many State-identified “priority species” (Table 3-1). The nearshore ecosystem supports aquatic plants and animals that feed the upper levels of the food web. Table 3-1. Priority wildlife species mapped along the Clallam County, Strait of Juan de Fuca shorelines (Sources: WDFW, WDNR) Terrestrial -

Securing the Border: Understanding the Threats and Strategies for the Northern Border”

Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area 300 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1300 Seattle, WA 98104 (206) 352-3600 fax (206) 352-3699 Prepared for the Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs “Securing the Border: Understanding the Threats and Strategies for the Northern Border” Testimony of Dave Rodriguez Director, Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) April 22, 2015 Chairman Johnson, distinguished members of this committee, my name is Dave Rodriguez and I have been the director of the Northwest HIDTA since June 1997. I first would like to thank the committee for its attention to exploring the national security threats facing our northern border. Additionally I wish to thank you for this opportunity for input from the Northwest HIDTA Program. The Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) incorporates 14 counties located on both the east and west sides of the Cascade Mountains. The western counties extend from the United States (US)-Canada border south to the Oregon border and include Clark, Cowlitz, King, Kitsap, Lewis, Pierce, Skagit, Snohomish, Thurston, and Whatcom County. The Eastern Washington counties include Benton, Franklin, Spokane, and Yakima. Within these vastly divergent jurisdictions, the Northwest HIDTA facilitates cooperation and joint efforts among more than 115 international, federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies. The Northwest HIDTA works with these agencies to identify drug threats and implement the strategies necessary to address them. Washington’s topography and location render it conducive to drug smuggling and production. The Washington section of the US-Canada border is approximately 430 miles in length, with 13 official ports of entry (POE). -

TARDIVEL-THESIS-2019.Pdf (1.146Mb)

NAVIGATING INDIGENOUS LEADERSHIP IN A SETTLER COLONIAL WORLD: RON AND PATRICIA JOHN ‘COME HOME’ TO STÓ:LÕ POLITICS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN SASKATOON By Angélique Tardivel © Copyright Angélique Tardivel, April 2019. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Reference in this thesis to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the University of Saskatchewan. The views and opinions of the author do not state or reflect those of the University of Saskatchewan, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. -

Aperçu De L'entente Sur Les Tiers Pays Sûrs Entre Le Canada Et Les États-Unis

APERÇU DE L’ENTENTE SUR LES TIERS PAYS SÛRS ENTRE LE CANADA ET LES ÉTATS-UNIS Publication no 2020-70-F Le 15 janvier 2021 Madalina Chesoi et Robert Mason Service d’information et de recherche parlementaires ATTRIBUTION Date Auteur Division Le 15 janvier 2021 Madalina Chesoi Division des affaires juridiques et sociales Robert Mason Division des affaires juridiques et sociales À PROPOS DE CETTE PUBLICATION Les études générales de la Bibliothèque du Parlement sont des analyses approfondies de questions stratégiques. Elles présentent notamment le contexte historique, des informations à jour et des références, et abordent souvent les questions avant même qu’elles deviennent actuelles. Les études générales sont préparées par le Service d’information et de recherche parlementaires de la Bibliothèque, qui effectue des recherches et fournit des informations et des analyses aux parlementaires ainsi qu’aux comités du Sénat et de la Chambre des communes et aux associations parlementaires, et ce, de façon objective et impartiale. La présente publication a été préparée dans le cadre du programme des publications de recherche de la Bibliothèque du Parlement, qui comprend notamment une série de publications lancées en mars 2020 sur la pandémie de COVID-19. Veuillez noter qu’en raison de la pandémie, toutes les publications de la Bibliothèque seront diffusées en fonction du temps et des ressources disponibles. © Bibliothèque du Parlement, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Aperçu de l’Entente sur les tiers pays sûrs entre le Canada et les États-Unis (Étude générale) Publication no 2020-70-F This publication is also available in English. TABLE DES MATIÈRES RÉSUMÉ 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... -

Churches Among Advocates Challenging Agreement That Sends Refugees to U.S

Churches among advocates challenging agreement that sends refugees to U.S. The Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) faces an important test this summer as political opponents keep an eye on the number of asylum seekers using irregular border crossings. Meanwhile, a federal court challenge of the Agreement as a violation of the Canadian charter mounted by the Canadian Council for Refugees, the Canadian Council of Churches and Amnesty International is working its way through the courts. In 2017, the RCMP intercepted more than 20,000 people crossing the border without going through normal ports of entry. The Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship the RCMP have intercepted nearly that half that – 9,481 people – up to May 2018, mostly at the Roxham Road entry south of Montreal. “Everyone recognizes that the circumstances of border crossing and asylum claims have changed dramatically in the last four to five years,” former Conservative cabinet minister Erin O’Toole told journalists before the House of Commons rose for a summer break June 20. “So I think it totally needs a total update If that means throwing it out and starting from scratch, I think Canada needs to be prepared for that. Because it was set up at a time when people would go to a port of entry and make an asylum claim. That’s the way it works. That’s not the way it’s happening anymore.” The New Democrats, however, want the agreement rescinded because of the treatment of migrants by the American administration. They hammered the government over news parents are being separated from children at the American border with Mexico due to U.S. -

CERC Migration Annual Report 2020-21

CERC Migration Annual Report 2020 - 2021 IMPROVING UNDERSTANDING THROUGH PANDEMIC TIMES CERC Migration Annual Report CERC Migration Annual Report 2020 - 2021 IMPROVING UNDERSTANDING THROUGH PANDEMIC TIMES 1.0 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 2 2.0 PEOPLE, GOVERNANCE & ADMINISTRATION 5 3.0 RESEARCH 9 4.0 ACADEMIC ENGAGEMENT 13 5.0 KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE 18 6.0 EXTENDING REACH THROUGH DIGITAL 25 COMMUNICATIONS & MEDIA RELATIONS 7.0 ANNEX Annex I: Research publications 29 Annex II: Pandemic borders project with openDemocracy 32 Annex III: Webinars 36 Annex IV: Migration Working Group 2020-21 40 Annex V: Sessions of the annual international conference 43 Annex VI: Media coverage 2020-21 45 1 CERC Migration Annual Report 1.0MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR The Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration (CERC Migration) program at Ryerson University has now completed its first, full year of operation in what history may one day call “the year of the century.” The COVID-19 pandemic introduced unforeseen challenges for starting up a new research operation, which challenged us to be responsive and adaptive, and led us to make advances in some areas where we would not have otherwise. At the same time, the world’s migrants – the subject that we observe and analyze through our research – have experienced extraordinary impacts as a result of the pandemic. The many structural injustices that chronically face migrants have been amplified through these times. Our research team aims to draw new insights and knowledge from this crisis to improve understanding and policy thinking, from the local to the global levels. Over the past year, many of our incoming researchers were delayed in their arrival to Canada due to border restrictions. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

Waters of the United States in Washington with Green Sturgeon Identified As NMFS Listed Resource of Concern for EPA's PGP

Waters of the United States in Washington with Green Sturgeon identified as NMFS Listed Resource of Concern for EPA's PGP (1) Coastal marine areas: All U.S. coastal marine waters out to the 60 fm depth bathymetry line (relative to MLLW) from Monterey Bay, California (36°38′12″ N./121°56′13″ W.) north and east to include waters in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Washington. The Strait of Juan de Fuca includes all U.S. marine waters: Clallam County east of a line connecting Cape Flattery (48°23′10″ N./ 124°43′32″ W.) Tatoosh Island (48°23′30″ N./124°44′12″ W.) and Bonilla Point, British Columbia (48°35′30″ N./124°43′00″ W.) Jefferson and Island counties north and west of a line connecting Point Wilson (48°08′38″ N./122°45′07″ W.) and Partridge Point (48°13′29″ N./122°46′11″ W.) San Juan and Skagit counties south of lines connecting the U.S.-Canada border (48°27′27″ N./ 123°09′46″ W.) and Pile Point (48°28′56″ N./123°05′33″ W.), Cattle Point (48°27′1″ N./122°57′39″ W.) and Davis Point (48°27′21″ N./122°56′03″ W.), and Fidalgo Head (48°29′34″ N./122°42′07″ W.) and Lopez Island (48°28′43″ N./ 122°49′08″ W.) (2) Coastal bays and estuaries: Critical habitat is designated to include the following coastal bays and estuaries in California, Oregon, and Washington: (vii) Lower Columbia River estuary, Washington and Oregon. All tidally influenced areas of the lower Columbia River estuary from the mouth upstream to river kilometer 74, up to the elevation of mean higher high water, including, but not limited to, areas upstream to the head of tide endpoint -

Unity in Diversity? Neoconservative Multiculturalism and the Conservative Party of Canada

Unity in Diversity? Neoconservative Multiculturalism and the Conservative Party of Canada John Carlaw Working Paper No. 2021/1 January 2021 The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration www.ryerson.ca/rcis www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration Working Paper No. 2021/1 Unity in Diversity? Neoconservative Multiculturalism and the Conservative Party of Canada John Carlaw Ryerson University Series Editors: Anna Triandafyllidou and Usha George The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration at Ryerson University. Working Papers present scholarly research of all disciplines on issues related to immigration and settlement. The purpose is to stimulate discussion and collect feedback. The views expressed by the author(s) do not necessarily reflect those of the RCIS or the CERC. For further information, visit www.ryerson.ca/rcis and www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration. ISSN: 1929-9915 Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License J. Carlaw Abstract Canada’s Conservative Party and former government’s (2006-2015) attempts to define and at times shift Canadian identity and notions of citizenship, immigration and multiculturalism to the right have been part of a significant political project featuring a uniquely creative and Canadian form of authoritarian populist politics in these realms. Their 2006 minority and 2011 majority election victories represented the culmination of a long march to power begun with the 1987 founding of the Reform Party of Canada. While they have at times purged themselves of some of the most blatant, anti-immigration elements of the discourses of their predecessor parties, continuities in its Canadian brand of authoritarian populist politics have continued in new forms since the founding of the new Conservative Party in 2003.