Intensifying Literacy Instruction in the Context of Tiered Interventions a View from Special Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literacy in India: the Gender and Age Dimension

OCTOBER 2019 ISSUE NO. 322 Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension TANUSHREE CHANDRA ABSTRACT This brief examines the literacy landscape in India between 1987 and 2017, focusing on the gender gap in four age cohorts: children, youth, working-age adults, and the elderly. It finds that the gender gap in literacy has shrunk substantially for children and youth, but the gap for older adults and the elderly has seen little improvement. A state-level analysis of the gap reveals the same trend for most Indian states. The brief offers recommendations such as launching adult literacy programmes linked with skill development and vocational training, offering incentives such as employment and micro-credit, and leveraging technology such as mobile-learning to bolster adult education, especially for females. It underlines the importance of community participation for the success of these initiatives. Attribution: Tanushree Chandra, “Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension”, ORF Issue Brief No. 322, October 2019, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-89622-04-1 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension INTRODUCTION “neither in terms of absolute levels of literacy nor distributive justice, i.e., reduction in gender Literacy is one of the most essential indicators and caste disparities, does per capita income of the quality of a country’s human capital. -

Literacy UN Acked: What DO WE MEAN by Literacy?

Memo 4 | Fall 2012 LEAD FOR LITERACY MEMO Providing guidance for leaders dedicated to children's literacy development, birth to age 9 L U: W D W M L? The Issue: To make decisions that have a positive What Competencies Does a Reader Need to impact on children’s literacy outcomes, leaders need a Make Sense of This Passage? keen understanding of literacy itself. But literacy is a complex concept and there are many key HIGH-SPEED TRAINS* service that moved at misunderstandings about what, exactly, literacy is. A type of high-speed a speed of one train was first hundred miles per Unpacking Literacy Competencies hour. Today, similar In this memo we focus specifically on two broad introduced in Japan about forty years ago. Japanese trains are categories of literacy competencies: skills‐based even faster, traveling The train was low to competencies and knowledge‐based competencies. at speeds of almost the ground, and its two hundred miles nose looked somewhat per hour. There are like the nose of a jet. Literacy many reasons that These trains provided high-speed trains are Reading, Wring, Listening & Speaking the first passenger popular. * Passage adapted from Good & Kaminski (2007) Skills Knowledge Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 6th ed. ‐ Concepts about print ‐ Concepts about the ‐ The ability to hear & world Map sounds onto letters (e.g., /s/ /p/ /ee/ /d/) work with spoken sounds ‐ The ability to and blend these to form a word (speed) ‐ Alphabet knowledge understand & express Based ‐ Word reading complex ideas ‐ Recognize -

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet Written by Belinda Dekker Dyslexia Support Australia https://dekkerdyslexia.wordpress.com/ Structured Literacy • Structured literacy is a scientifically researched based approach to the teaching of reading. Structured literacy can be in the form of teachers trained in the use of structured literacy methodologies and programs that adhere to the fundamental and essential components of structured literacy. • Structure means that there is a step by step clearly defined systematic process to the teaching of reading. Including a set procedure for introducing, reviewing and practicing essential concepts. Concepts have a clearly defined sequence from simple to more complex. Each new concept builds upon previously introduced concepts. • Knowledge is cumulative and the program or teacher will use continuous assessment to guide a student’s progression to the next clearly defined step in the program. An important fundamental component is the automaticity of a concept before progression. • Skills are explicitly or directly taught to the student with clear explanations, examples and modelling of concepts. ‘The term “Structured Literacy” is not designed to replace Orton Gillingham, Multi-Sensory or other terms in common use. It is an umbrella term designed to describe all of the programs that teach reading in essentially the same way'. Hal Malchow. President, International Dyslexia Association A Position Statement on Approaches to Reading Instruction Supported by Learning Difficulties Australia "LDA supports approaches to reading instruction that adopt an explicit structured approach to the teaching of reading and are consistent with the scientific evidence as to how children learn to read and how best to teach them. -

Orton-Gillingham Or Multisensory Structured Language Approaches

JUST THE FACTS... Information provided by The International Dyslexia Association® ORTON-GILLINGHAM-BASED AND/OR MULTISENSORY STRUCTURED LANGUAGE APPROACHES The principles of instruction and content of a Syntax: Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the multisensory structured language program are essential sequence and function of words in a sentence in order for effective teaching methodologies. The International to convey meaning. This includes grammar, sentence Dyslexia Association (IDA) actively promotes effective variation, and the mechanics of language. teaching approaches and related clinical educational Semantics: Semantics is that aspect of language intervention strategies for dyslexics. concerned with meaning. The curriculum (from the beginning) must include instruction in the CONTENT: What Is Taught comprehension of written language. Phonology and Phonological Awareness: Phonology is the study of sounds and how they work within their environment. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound PRINCIPLES OF INSTRUCTION: How It Is Taught in a given language that can be recognized as being Simultaneous, Multisensory (VAKT): Teaching is distinct from other sounds in the language. done using all learning pathways in the brain Phonological awareness is the understanding of the (visual/auditory, kinesthetic-tactile) simultaneously in internal linguistic structure of words. An important order to enhance memory and learning. aspect of phonological awareness is phonemic awareness or the ability to segment words into their Systematic and Cumulative: Multisensory language component sounds. instruction requires that the organization of material follows the logical order of the language. The Sound-Symbol Association: This is the knowledge of sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic the various sounds in the English language and their elements and progress methodically to more difficult correspondence to the letters and combinations of material. -

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program The International Dyslexia Association identifies Structured Literacy as an effective instructional approach for meeting the needs of students who struggle with learning to read. Structured Literacy utilizes systematic, explicit instruction to teach decoding skills including phonology, sound-symbol association, syllable types, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Structured Literacy instruction has been around for over a century and is sometimes referred to as systematic reading instruction, phonics-based reading instruction, the Orton-Gillingham Approach, or synthetic phonics, among other names. The SIPPS (Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words) program, developed by Dr. John Shefelbine, is a multilevel program that develops the word-recognition strategies and skills that enable students to become independent and confident readers and writers. Dr. Shefelbine’s research emphasizes systematic instruction, and in many ways parallels the Orton-Gillingham Approach. Structured Literacy The table below notes the elements of Structured Literacy aligned to the SIPPS program. Elements of Structured Literacy SIPPS Phonology Defined as the study of sound structure of spoken Phonological awareness activities appear in every words; includes rhyming, counting words in lesson in SIPPS Beginning, Extension, and Plus. spoken sentences, clapping syllables in spoken These activities begin with segmenting and words, and phonemic awareness (manipulation of blending, include rhyme, and increase in complexity sounds). to dropping and substituting phonemes. Sound-Symbol Association Defined as connecting sounds to print, including Spelling-sounds are explicitly taught throughout the blending and segmenting. This should occur two program. Sounds are taught in order of utility, which ways: visual to auditory (reading) and auditory to allows students to quickly begin to read connected visual (spelling). -

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: the Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C. (2018). Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy. OT Practice 23(15), 14–18. The Research: Occupational therapy interventions for visual processing skills were found to positively affect academic achievement and social participation. Key elements of intervention activities needed for progress include: fine motor activities, copying skills, gross motor activities, and a high level of cognitive interaction with completing activities. What is it? Visual information processing skills refers to “a group of visual cognitive skills used for extracting and organizing visual information from the environment and integrating this information with other sensory modalities and higher cognitive functions”. Visual information processing skills are divided into three components: visual spatial, visual analysis, and visual motor. Visual motor integration skills (i.e. eye-hand coordination) are related to an individual’s ability to combine visual information processing skills with fine motor or gross motor movement. Studies have found that visual motor integration is a component of reading skills in children in elementary school Specific Combination of Intervention Strategies Found to be Successful Fine motor activities ● Intervention activities: Manipulating small items (e.g., beads, coins); opening the thumb web space, separating the two sides of the hand; practicing finger isolation; -

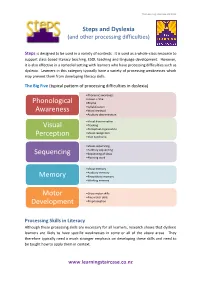

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

Adolescent Literacy Addressing the Needs of Students in Grades 4–12

Adolescent Literacy Addressing the Needs of Students in Grades 4–12 By Joan Sedita Literacy skills in the 21st century are more essential than ever for success in education, work, citizenship, and our personal lives. However, far too many older students and adults do not have the necessary reading and writing skills to succeed in postsecondary education or the ever-increasing number of jobs that require strong literacy skills. During the 1990s and through 2008, significant emphasis was placed on the use of research to determine how children learn to read and why some students struggle with reading. Early literacy achievement, however, is not necessarily a guarantee that literacy skills will continue to grow as students move beyond Grade 3. In Reading Next, it is noted that: Recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading results indicate that efforts to improve K–3 literacy are paying off at the 4th-grade level, but these improvements do not necessarily translate into better achievement among adolescents… Comparing the most recent NAEP results for all three grade levels (i.e., 4, 8, and 12) to those from 1992, the percentage of students scoring proficient has significantly improved among 4th graders, but not among 8th and 12th graders. (Biancarosa & Snow, 2006, pp. 7–8) Scores at the secondary level, where there has been relatively little investment, have remained flat since the 1970s (Heller & Greenleaf, 2007). The following observation from Time to Act: An Agenda for Advancing Adolescent Literacy for College and Career Success sums up the challenges faced after Grade 3: The truth is that good early literacy instruction does not inoculate students against struggle or failure later on. -

1 Writing Systems and Orthographies Volume 2: Literacy Barbara Burnaby the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education

Writing Systems and Orthographies Volume 2: Literacy Barbara Burnaby The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education 1 Introduction Academic discussion of writing systems (grammatology) extends to both detailed descriptions of the mechanics of particular systems and/or visceral theoretical debates involving linguistics, anthropology, archaeology, sociology, history, and/or psychology. Issues are raised concerning competing views of reality (e.g. Street, 1984, p. 130) and the power of Western thought in relation to non-Western knowledge and its dissemination (e.g. DeFrancis, 1989, p. xi). This review of literature leans towards cross-national and comparative studies, although it is biassed by the writer's limitation to works in English. Under the headings of definitions, typologies, values, first and second language literacy learning, and other factors, it only touches the surface of a massive body of work. What is a Writing System? Stubbs (1980, p. viii) rather dramatically states ...there is...nothing approaching a coherent theory about the relations between reading and writing, or between written and spoken language, or about the place of written language in society and the purposes it serves. 2 Authors generally agree with Gelb (1963, p. 12) that writing is `a system of human intercommunication by means of conventional visible marks' (italics in the original). If one construes `marks' liberally, body sign languages (as in sign languages used by the deaf) can be included, and the definition encompasses systems such as musical notation and those that indicate kinesics (e.g. Basso & Anderson, 1977). Gauer, equating writing with information storage, takes this stance (1984, p. 14). Many others (e.g. -

1 the Whole Language Approach to Reading

1 The Whole Language Approach to Reading: An empiricist critique A revised version of: Hempenstall, K. (1996). The whole language approach to reading: An empiricist critique. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 1(3), 22-32. Historically, the consideration of learning disability has emphasised within-person factors to explain the unexpected difficulty that academic skill development poses for students with such disability. Unfortunately, the impact of the quality of initial and subsequent instruction in ameliorating or exacerbating the outcomes of such disability has received rather less exposure until recently. During the 1980’s an approach to education, whole language, became the major model for educational practice in Australia (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Employment, Education, and Training, 1992). Increasing controversy developed, both in the research community (Eldredge, 1991; Fields & Kempe, 1992; Gersten & Dimino, 1993; Liberman & Liberman, 1990; Mather, 1992; McCaslin, 1989; Stahl & Miller, 1989; Vellutino, 1991; Weir, 1990), and in the popular press (Hempenstall, 1994, 1995; Prior, 1993) about the impact of the approach on the attainments of students educated within this framework. In particular, concern was expressed (Bateman, 1991; Blachman, 1991; Liberman, Shankweiler, & Liberman, 1989; Yates, 1988) about the possibly detrimental effects on "at-risk" students (including those with learning disabilities). Whole language: History The whole language approach has its roots in the meaning-emphasis, whole-word model of teaching reading. Its more recent relation was an approach called "language experience" which became popular in the mid-1960's. The language experience approach emphasized the knowledge which children bring to the reading situation - a position diametrically opposed to the Lockian view of "tabula rasa" (the child's mind as a blank slate on which education writes its message). -

Why Not Phonics and Whole Language?

Why Not Phonics and Whole Language? Marilyn Jager Adams Bolt Beranek and Newman, Inc. Bernice Cullinan has a map of the United States that she is fond of displaying at conferences. On her map, any state that has joined the whole language movement is brightly colored; those that are leaning toward whole language are tinged; the rest are left white. Her point is that very few states are still white. Leaving aside questions of nature of Cullinan’s measurement protocol and the grain of her analysis, her essential point seems somehow to ring true. Whole language is a very active and prominent movement. More and more, it dominates journals, conference agendas, workshop and in-service opportunities, course offerings, and even basal design and marketing strategies. The only conceivable explanation for the burgeoning popularity of the whole language movement is that something within it strikes a deeply resonant chord in many, many teachers and reading professionals. For this reason alone, it is both timely and welcome that The Orton Dyslexia Society should devote a special symposium to it. Yet, detractors from the whole language movement are at least as adamant. And, thus, we find ourselves in the midst of a full-scale reading “war.” (Rothman 1990) Listening to either side and looking to the other, it is difficult to believe that so many could be so wrong. And, indeed, toward mediating or understanding any deadlocked argument, the rule of thumb is that both sides are right but are talking past each other; most often, their principal concerns well from wholly different issues within the domain. -

LRA Dyslexia Literacy Research Report 1.Pdf

DYSLEXIA, LITERACY DIFFICULTIES AND INSTRUCTION Peter Johnston The University at Albany Donna Scanlon The Child Research and Study Center The University at Albany Literacy Research Association Literacy Research Report Draft October 28th, 2020 Request for comment This is a draft of a Literacy Research Report for the Literacy Research Association. We encourage LRA members to send constructive comment and critique to either author ([email protected] or [email protected]). We will attempt to engage any critique in the document's revision and in the presentation at LRA. Dyslexia, Literacy Difficulties anD Instruction There is no doubt that some children experience more difficulty than others becoming literate, often at great emotional, intellectual, social and economic cost, to themselves but also to those who love and care for them, and for society at large. The causes of those difficulties, and what to do about them, have been the source of vast research and sometimes heated disagreement among researchers and educators – disagreements that, in one form or another, go back well over a century. The current focus of this attention, from the media, some researchers, parents and politicians, is on the construct dyslexia – a term used to describe learners who experience extreme/serious difficulty with the word reading aspect of the reading process. In 2019 alone there were expositions about dyslexia on National Public Radio, the Public Broadcasting Service, The New York Times, Education Week, and numerous other major outlets, each asserting with certainty that dyslexia is a central cause of reading difficulty and asserting a singular instructional solution. Promoted by a coalition of certain researchers, parents, politicians, and private, for-profit and non-profit education entities, this proposed solution, which they refer to as “the science of reading” (SOR), calls for an approach to reading instruction for beginning and struggling readers that focuses on a particular, almost exclusively phonics-based, approach to developing skill with word identification.