MA Thesis 5.18.18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati News Record. Tuesday, April 1, 1969. Vol. LVI, No

~'I ..,)\C£N""'~ . ' VU6"'1;.· University of ·Cincinn.a.ti .~'IC:: II'~ NEWS RECORD 11 .1J~ "It Published. Tuesdays and Fridays during the Academic Year except as scheduled. '.1::>. ',-"/ ------------------------.----- . V '<119 _ '19 ~ " Vol. 56 Cincinnati, Ohio Tuesday, -Aprll 1, 1969 No. 35J '/ '(ourtWarlling To Calhoun Youths (al~ed:Rights'lnvasion' By AelU by Lew Moores much as possible and the depraved else. As long as valid laws are not peddlers of these mind-affecting A statem.ent'lss,ued by Juvenile violated by the. juvenile there drugs.." _ sJ:1ouldn'tlje cause for legitimate Court Judge"BenjamIn Schwartz Fred, Dewey, Chairman of, the concern or what he 'calls "police on Monday, Mafch. 21) warning harassment. " I juveniles to ..stop, loitering on local chapter of the American Calhoun Street;has evoked charges Civil Liberties Union, asserted "If respect for 'law and order is- ,of excessive ":agthQrity from the that the Juvenile. Court cannot to be 'fostered among the youth of Ci n ci n nat i 'Ch'api.er of the compel a juvenile to obey its Hamilton County, the' Juvenile American Civil Liberties Union. warning. It is a statutory court Cou rt should not threaten The 'statement originating. from and cannot assume any. powers children before they have been officials of the Hamilton County other than those expressly stated guilty of misconduct which Juvenile, Court cautions juveniles in the Ohio statutes. '-. warrants official action~" stated that loitering. on Calhoun 'Street Only upon Issuance of an Professor Dewey.. could result in both the juveniles a ffadavit alleging neglect, Professor Dewey declared the and their parents being summoned dependency, 'or delinquincy to a presumption of innocence should to court if the juvenile fails to juvenile and parent can the be in favor of the juvenile until 'obey a warning .letter issued by Juvenile Court exercise any officially charged with ,a violation the polic~, __~ . -

Team 252 Team 910 Team 919 Team 336 Team 704 Team

TEAM 336 Scouting report: With eight Manning into a mix of big men TEAM 919 n Rodney Rogers, Durham Hillside watch. But it wouldn’t be all perimeter NBA All-Star Game appear- that includes a former NBA MVP, n David West, Garner flash as Rogers and West would bring n Chris Paul, West Forsyth n Pete Maravich, Raleigh Broughton ances among them, Manning and McAdoo, and one of the ACC’s Scouting report: With Maravich and enough muscle to match just about any n Lou Hudson, Dudley n John Wall, Raleigh Word of God Hudson give this team a pair of early stars, Hemric, the Triad Wall in the backcourt and McGrady on front line. n Danny Manning, Page DIALING UP OUR dynamic weapons. Hudson would would have a team that would be n Tracy McGrady, Durham Mount Zion the wing, no team would be as fun to n Dickie Hemric, Jonesville slide nicely into a backcourt on better footing to compete with STATE’S BEST n Bob McAdoo, Smith with Paul. And by throwing some of the state’s other squads. While he is the brightest basketball star on the West Coast, some of NBA MVP Stephen Curry’s shine gets reflected back on his home state. Raised in Charlotte and educated at Davidson, Curry’s triumphs add new chapters to North Carolina’s already impressive hoops tradition. Since picking an all-time starting five of players who played their high school ball in North Carolina might be difficult, Fayetteville Observer staff writer Stephen Schramm has chosen teams based on the state’s six area codes. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

Deters Talks

^ V*''*IT* >t the weather Inside today Variable cloudiness today with chance of a few showers. Highs In mid Area news . 1-2B Family ....... ....6-7A to upper 60s. Partial clearing and^ool Classified . 6-lOB Gardening ........8A C o m ics............. IIB Obituaries .... 12A tonight. Low In upper '30s to mid «>s. Dear Abby___ IIB S p o rts.............3-5B Mostly sunny hut cool Friday with high Elditorial ...........4A 55-60. Chance of rain 30% today, 20% tonight, 10% Friday. National weather map on Page 7B. deters talks UNITED NATIONS (UPI) - One Cyrus Vance held with his counter the Palestinians at Geneva remained of the most intense bursts of parts from the Soviet Union and Mid unresolved — the Arabs still insist diplomatic activity on the Middle dle Eastern nations. the Palestinian Liberation Organiza East conflict has ended without an The Americans and Soviets issued tion go to Geneva and the Israelis agreement to reconvene the Geneva a joint statement this weekend still refuse to bargain with the PLO. peace talKs. recognizing for the first time the A joint U.S.-Israeli statement was High U.S. officials said Wednesday “rights” of the Palestinians and released after the Carter-Dayan the issue of who will represent the calling for their participation at meeting saying the two sides had St?’" Palestinians remains the principal Geneva, arousing speculation a made progess on resolving the obstacle to resuming the Geneva con breaKthrough was imminent. “remaining obstacles " to resuming a ference, and it will be weeKs before it Then President Carter and Vance Geneva conference. -

Winners for the 29Th Annual Sports Emmy Awards Is Also Available on the National Television Academy’S Website At

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WINNERS OF 29th ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Frank Chirkinian Honored with Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – April 28, 2008 – The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) announced the winners tonight of the 29th Annual Sports Emmy® Awards at a special ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City. The awards were presented by a distinguished group of sports figures and television personalities including veteran Bob Costas (host of NBC’s upcoming Olympic coverage in Beijing and NBC’s Football Night in America; host of HBO’s “Costas Now” and “Inside the NFL”); Cris Collinsworth (sports analyst for NBC’s NFL coverage and HBO’s “Inside the NFL”); Jim Nantz (lead play-by-play announcer of The NFL on CBS and play-by-play broadcaster for NCAA college basketball and golf on CBS); Joe Buck (sports announcer FOX Sports NFL and MLB); Charles Barkley (11-time NBA All-Star and eight season veteran as NBA analyst for TNT); Mike Tirico (host of ESPN’s Monday Night Football, The Masters and his daily show on ESPN Radio); Phil Simms (Super Bowl XXI MVP and lead game analyst The NFL on CBS); Tim McCarver (two time- St. Louis Cardinals World Series Champion and sports announcer for MLB on FOX); Chip Carey (play-by-play for MLB Playoffs on TBS); Lisa Salters (ESPN reporter since 2000 now seen on the new E:60 program); Jay Bilas (studio and game analyst for NCAA college basketball for 13-years at ESPN); Cris Carter (3-time NFL All- Pro, 8 straight Pro-Bowls, analyst HBO’s Inside the NFL and Yahoo Sports); and Frank Deford (senior contributing writer for Sports Illustrated and commentator for HBO’s Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel). -

THE LITERACY CONNECTION - Opening Our Doors to the Dear Neighbor by Pat Andrews, CSJ

Online Update 6.1.7 May 18, 2021 A publication of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Boston Photo by: Ann Marie Garrity, CSJ THE LITERACY CONNECTION - Opening Our Doors to the Dear Neighbor by Pat Andrews, CSJ he Sisters of Saint Joseph and The Literacy Connection assisted in the fight against- COVID-19 by opening our doors to the neighborhood. For the third time, our neighborhood community arrived for their COVID-19 vaccine shots. On May 14, we Tsurprised when the van arrived from the Whittier Street Health Center, Dorchester, MA - a contingent of Army and Air Force medical personnel exited the vehicle! (Being an Air Force brat all my life, I saluted!) This group of soldiers belong to a medical unit stationed at Otis Air Base on Cape Cod that was formed to assist the Commonwealth in its battle against the virus. The Literacy Connection has been working with Heloisa Galvao, Director of the Brazilian Women's Group in Brighton, MA. Heloisa has been able to contact the medical staff needed and The Literacy Connection has been able to provide the space and protocals needed to follow all COVID-19 procedures. This is one of many examples of the commitment and collaboration among programs here in the Allston-Brighton Community. We are grateful to be an active member of this community. We can't do all this alone. I am exceedingly grateful to these pandemic angels who have graciously welcomed nervous older visitors, cranky children (placated with lollipops) and the younger generation. Thank you to Sisters Jo Perico, Rosemary Brennan, Carlotta Gilarde, Elizabeth Toomey, Kay Decker, Gail Donohue, Kathy Berube, Mary Rita Grady,Cathy Mozzicato as well as CSJ employee Chi Leung. -

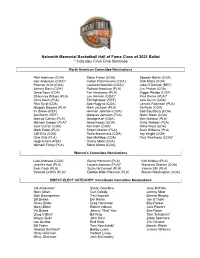

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Ucla Men's Basketball

UCLA MEN’S BASKETBALL March 25, 2006 Bill Bennett/Marc Dellins /310-206-7870 For Immediate Release UCLA Men’s Basketball/NCAA Between Game Notes NO. 7 UCLA PLAYS NO. 4 MEMPHIS IN NCAA REGIONAL FINAL IN OAKLAND ON SATURDAY, WINNER ADVANCES TO “FINAL FOUR” IN INDIANAPOLIS; BRUINS EDGE GONZAGA 73-71 ON THURSDAY IN “SWEET 16” CONTEST No. 7/No. 8 UCLA (30-6/Pac-10 14-4, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 2 Seed) vs. No. 4/No. 3 MEMPHIS (33-3/Conference USA 13-1, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 1 Seed) - Saturday, March 25/Oakland, CA/Oakland Arena/4:05 p.m. PT/TV- CBS, Gus Johnson and Len Elmore/Radio-570AM, with Chris Roberts and Don MacLean. Tentative UCLA Starters F- 21 Cedric Bozeman 6-6, Sr., 7.8, 3.2 F-23 Luc Richard Mbah a Moute 6-8, Fr., 9.1, 8.1 C- 15 Ryan Hollins 7-01/2, Sr., 6.7, 4.5 G-1 Jordan Farmar 6-2, So., 13.6, 2.5 G-4 Arron Afflalo 6-4, So., 16.2, 4.3 UCLA vs. Memphis – The Tigers advanced with an 80-64 victory over Bradley, led by Rodney Carney’s 23 points. Memphis has won 22 of its last 23 games and has a seven-game winning streak. This will be the team’s second meeting this season – on Nov. 23 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, Memphis defeated UCLA 88-80 in an NIT Season Tip-Off semifinal. Last Meeting - Nov. 23 – No. 11 Memphis 88, No. -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Downtrodden Yet Determined: Exploring the History Of

DOWNTRODDEN YET DETERMINED: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF BLACK MALES IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL AND HOW THE PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ADDRESSES THEIR WELFARE A Dissertation by JUSTIN RYAN GARNER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, John N. Singer Committee Members, Natasha Brison Paul J. Batista Tommy J. Curry Head of Department, Melinda Sheffield-Moore May 2019 Major Subject: Kinesiology Copyright 2019 Justin R. Garner ABSTRACT Professional athletes are paid for their labor and it is often believed they have a weaker argument of exploitation. However, labor disputes in professional sports suggest athletes do not always receive fair compensation for their contributions to league and team success. Any professional athlete, regardless of their race, may claim to endure unjust wages relative to their fellow athlete peers, yet Black professional athletes’ history of exploitation inspires greater concerns. The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) to explore and trace the historical development of basketball in the United States (US) and the critical role Black males played in its growth and commercial development, and 2) to illuminate the perspectives and experiences of Black male professional basketball players concerning the role the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), collectively considered as the Players Association for this study, played in their welfare and addressing issues of exploitation. While drawing from the conceptual framework of anti-colonial thought, an exploratory case study was employed in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a list of Black male professional basketball players who are members of the Players Association. -

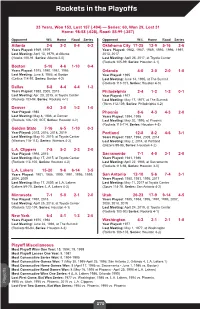

Rockets in the Playoffs

Rockets in the Playoffs 33 Years, Won 153, Lost 157 (.494) — Series: 60, Won 29, Lost 31 Home: 98-58 (.628), Road: 55-99 (.357) Opponent W-L Home Road Series Opponent W-L Home Road Series Atlanta 2-6 2-2 0-4 0-2 Oklahoma City 17-25 12-9 5-16 2-6 Years Played: 1969, 1979 Years Played: 1982, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997, Last Meeting: April 13, 1979, at Atlanta 2013, 2017 (Hawks 100-91, Series: Atlanta 2-0) Last Meeting: April 25, 2017, at Toyota Center (Rockets 105-99, Series: Houston 4-1) Boston 5-16 4-6 1-10 0-4 Years Played: 1975, 1980, 1981, 1986 Orlando 4-0 2-0 2-0 1-0 Last Meeting: June 8, 1986, at Boston Year Played: 1995 (Celtics 114-97, Series: Boston 4-2) Last Meeting: June 14, 1995, at The Summit (Rockets 113-101, Series: Houston 4-0) Dallas 8-8 4-4 4-4 1-2 Years Played: 1988, 2005, 2015 Philadelphia 2-4 1-2 1-2 0-1 Last Meeting: Apr. 28, 2015, at Toyota Center Year Played: 1977 (Rockets 103-94, Series: Rockets 4-1) Last Meeting: May 17, 1977, at The Summit (76ers 112-109, Series: Philadelphia 4-2) Denver 4-2 3-0 1-2 1-0 Year Played: 1986 Phoenix 8-6 4-3 4-3 2-0 Last Meeting: May 8, 1986, at Denver Years Played: 1994, 1995 (Rockets 126-122, 2OT, Series: Houston 4-2) Last Meeting: May 20, 1995, at Phoenix (Rockets 115-114, Series: Houston 4-3) Golden State 7-16 6-5 1-10 0-3 Year Played: 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 Portland 12-8 8-2 4-6 3-1 Last Meeting: May 10, 2019, at Toyota Center Years Played: 1987, 1994, 2009, 2014 (Warriors 118-113), Series: Warriors 4-2) Last Meeting: May 2, 2014, at Portland (Blazers 99-98, Series: Houston 4-2) L.A. -

2012-13 BOSTON CELTICS Media Guide

2012-13 BOSTON CELTICS SEASON SCHEDULE HOME AWAY NOVEMBER FEBRUARY Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa OCT. 30 31 NOV. 1 2 3 1 2 MIA MIL WAS ORL MEM 8:00 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 WAS PHI MIL LAC MEM MEM TOR LAL MEM MEM 7:30 7:30 8:30 1:00 7:30 7:30 7:00 8:00 7:30 7:30 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 CHI UTA BRK TOR DEN CHA MEM CHI MEM MEM MEM 8:00 7:30 8:00 12:30 6:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 DET SAN OKC MEM MEM DEN LAL MEM PHO MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:AL30L-STAR 7:30 9:00 10:30 7:30 9:00 7:30 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 ORL BRK POR POR UTA MEM MEM MEM 6:00 7:30 7:30 9:00 9:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 DECEMBER MARCH Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa 1 1 2 MIL GSW MEM 8:30 7:30 7:30 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 MEM MEM MEM MIN MEM PHI PHI MEM MEM PHI IND MEM ATL MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 MEM MEM MEM DAL MEM HOU SAN OKC MEM CHA TOR MEM MEM CHA 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 1:00 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 MEM MEM CHI CLE MEM MIL MEM MEM MIA MEM NOH MEM DAL MEM 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:30 8:00 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 MEM MEM BRK MEM LAC MEM GSW MEM MEM NYK CLE MEM ATL MEM 7:30 7:30 12:00 7:30 10:30 7:30 10:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 30 31 31 SAC MEM NYK 9:00 7:30 7:30 JANUARY APRIL Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 MEM MEM MEM IND ATL MIN MEM DET MEM CLE MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00