'Real Utopias'?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computers and Economic Democracy

Rev.econ.inst. vol.1 no.se Bogotá 2008 COMPUTERS AND ECONOMIC DEMOCRACY Computadores y democracia económica Allin Cottrell; Paul Cockshott Ph.D. in Economics, professor of Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, USA, [[email protected]]. Ph.D. in Computer Science, researcher of the Glasgow University, Glasgow, United Kingdom, [[email protected]].. The collapse of previously existing socialism was due to causes embedded in its economic mechanism, which are not inherent in all possible socialisms. The article argues that Marxist economic theory, in conjunction with information technology, provides the basis on which a viable socialist economic program can be advanced, and that the development of computer technology and the Internet makes economic planning possible. In addition, it argues that the socialist movement has never developed a correct constitutional program, and that modern technology opens up opportunities for democracy. Finally, it reviews the Austrian arguments against the possibility of socialist calculation in the light of modern computational capacity and the constraints of the Kyoto Protocol. [Keywords: socialist planning, economic calculation, environmental constraints; JEL: P21, P27, P28] El colapso del socialismo anteriormente existente obedeció a causas integradas en su mecanismo económico, que no son inherentes a todos los socialismos posibles. El artículo muestra que la teoría económica marxista, junto con la informática, proporciona el fundamento para adelantar un programa económico socialista viable y que el desarrollo de la informática y de Internet hace posible la planificación económica. Además, argumenta que el movimiento socialista nunca desarrolló un programa constitucional correcto y que la tecnología moderna abre nuevas oportunidades para la democracia. -

What We Know and Do Not Know About the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 11, Number 1—Winter 1997—Pages 51–72 What We Know and Do Not Know About the Natural Rate of Unemployment Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence F. Katz lmost 30 years ago, Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968) developed the concept of the "natural rate of unemployment." In what must be one of Athe longest sentences he ever wrote, Milton Friedman explained: "The natural rate of unemployment is the level which would be ground out by the Wal- rasian system of general equilibrium equations, provided that there is imbedded in them the actual structural characteristics of the labor and commodity markets, in- cluding market imperfections, stochastic variability in demands and supplies, the cost of gathering information about job vacancies and labor availabilities, the costs of mobility, and so on." Over the past three decades a large amount of research has attempted to formalize Friedman's long sentence and to identify, both theo- retically and empirically, the determinants of the natural rate. It is this body of work we assess in this paper. We reach two main conclusions. The first is that there has been considerable theoretical progress over the past 30 years. A framework has emerged, organized around two central ideas. The first is that the labor market is a market with a high level of traffic, with large flows of workers who have either lost their jobs or are looking for better ones. This by itself implies that there must be some "frictional unemployment." The second is that the nature of relations between firms and workers leads to wage setting that often differs substantially from competitive wage setting. -

Mill's "Very Simple Principle": Liberty, Utilitarianism And

MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE": LIBERTY, UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM MICHAEL GRENFELL submitted for degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H^S £ S F 6SI6 ABSTRACT OF THESIS MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE'*: LIBERTY. UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM 1 The thesis aims to examine the political consequences of applying J.S. Mill's "very simple principle" of liberty in practice: whether the result would be free-market liberalism or socialism, and to what extent a society governed in accordance with the principle would be free. 2 Contrary to Mill's claims for the principle, it fails to provide a clear or coherent answer to this "practical question". This is largely because of three essential ambiguities in Mill's formulation of the principle, examined in turn in the three chapters of the thesis. 3 First, Mill is ambivalent about whether liberty is to be promoted for its intrinsic value, or because it is instrumental to the achievement of other objectives, principally the utilitarian objective of "general welfare". -

The Road to Serfdom

F. A. Hayek The Road to Serfdom ~ \ L f () : I~ ~ London and New York ( m v ..<I S 5 \ First published 1944 by George Routledge & Sons First published in Routledge Classics 2001 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4 RN 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Repri nted 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006 Routledge is an imprint ofthe Taylor CJ( Francis Group, an informa business © 1944 F. A. Hayek Typeset in Joanna by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall All rights reserved. No part ofthis book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0-415-25543-0 (hbk) ISBN 10: 0-415-25389-6 (pbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-25543-1 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-25389-5 (pbk) CONTENTS PREFACE vii Introduction 1 The Abandoned Road 10 2 The Great Utopia 24 3 Individualism and Collectivism 33 4 The "Inevitability" of Planning 45 5 Planning and Democracy 59 6 Planning and the Rule of Law 75 7 Economic Control and Totalitarianism 91 8 Who, Whom? 1°5 9 Security and Freedom 123 10 Why the Worst Get on Top 138 11 The End ofTruth 157 12 The Socialist Roots of Nazism 171 13 The Totalitarians in our Midst 186 14 Material Conditions and Ideal Ends 207 15 The Prospects of International Order 225 2 THE GREAT UTOPIA What has always made the state a hell on earth has been precisely that man has tried to make it his heaven. -

THE MAGIC MONEY TREE: the Case Against Modern Monetary Theory

THE MAGIC MONEY TREE: The case against Modern Monetary Theory Antony P. Mueller The Adam Smith Institute has an open access policy. Copyright remains with the copyright holder, but users may download, save and distribute this work in any format provided: (1) that the Adam Smith Institute is cited; (2) that the web address adamsmith.org is published together with a prominent copy of this notice; (3) the text is used in full without amendment [extracts may be used for criticism or review]; (4) the work is not re–sold; (5) the link for any online use is sent to info@ adamsmith.org. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect any views held by the publisher or copyright owner. They are published as a contribution to public debate. © Adam Smith Research Trust 2019 CONTENTS About the author 4 Executive summary 5 Introduction 7 1 What is Modern Monetary Theory? 10 2 Mosler Economics 16 3 Theoretical foundations 21 4 The Neo-Marxist Roots of MMT 26 5 Main points of critique 34 Conclusion 45 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Antony P. Mueller studied economics, political science, and philosophy along with foreign relations in Germany with study stays in the United States (Center for the Study of Public Choice in Blacksburg, Va.), in England, and in Spain and obtained his doctorate in economics from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU). He was a Fulbright Scholar in the United States and a visiting professor in Latin America - including two stays at the Universidad Francisco Marroquin (UFM) in Guatemala. -

Economic Planning I Eco 441 Main Course

COURSE GUIDE ECO 441 ECONOMIC PLANNING I Course Team Dr. Akinade Olushina matthew (Course Developer)-Senior Research Fellow Economist Associate Research Firm Prof. Ogunleye Edward Oladipo (Course Editor) Department of Economics Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA ECO 441 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters University Village Plot 91, Cadastral Zone Nnamdi Azikiwe Expressway Jabi, Abuja Lagos Office 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island, Lagos e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed 2018 ISBN: 978- 978-058-039-5 ii ECO 441 COURSE GUIDE CONTENT PAGE Introduction……………………………………………....iv Course Content …………………………………………..iv Course Aims………………………………………………iv Course Objectives…………………………………………v Working through This Course…………………………….v Course Materials…………………………………………vi Study Units……………………………………………….vi Textbooks and References……………………………....vii Assignment File…………………………………………..xi Presentation Schedule…………………………………….xi Assessment………………………………………………..xi Tutor-Marked Assignment (TMAs)……………………....xi Final Examination and Grading………………………….xii Course Marking Scheme…………………………………xii Course Overview…………………………………………xii How to Get the Most from This Course…………………xiii Tutors and Tutorials……………………………………..xiii Summary…………………………………………………xvi iii ECO 441 COURSE GUIDE INTRODUCTION ECO 441 is designed to introduce to you and to teach you the basics -

Keynes, the Keynesians and Monetarism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Congdon, Tim Book — Published Version Keynes, the Keynesians and Monetarism Provided in Cooperation with: Edward Elgar Publishing Suggested Citation: Congdon, Tim (2007) : Keynes, the Keynesians and Monetarism, ISBN 978-1-84720-139-3, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781847206923 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182382 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode www.econstor.eu © Tim Congdon, 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Introduction to Economics Broadly Considered Jeff E

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Economics Faculty Research and Publications Economics, Department of 1-1-2001 Introduction to Economics Broadly Considered Jeff E. Biddle John B. Davis Marquette University, [email protected] Steven G. Medema Published version. "Introduction," in Economics Broadly Considered: Essays in Honor of Warren J. Samuels. London: Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2001: 1-29. Permalink. © 2001 Taylor & Francis (Routledge). Used with permission. Introduction Economics broadly considered: a glance at Warren J. Samuels' contributions to economics Jeff E. Biddle, John B. Davis, and Steven G. Medema Warren J. Samuels was born in New York City and grew up in Miami, Florida. He earned his B.A. from the University of Miami in 1954 and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin in 1957. After holding positions at the University of Missouri, Georgia State University, and the University of Miami, Samue1s was Professor of Economics at Michigan State University from 1968 until his retirement in 1998 (for biographical details, see Samuels 1995 and Blaug 1999). Samuels' contributions to economics range widely across the discipline, but his most significant work, and the largest share of his corpus, falls within the history of economic thought, the economic role of government (and par ticularly law and economics), and economic methodology. All of this work has been undertaken against the backdrop of an institutional approach to economics and economic thought. Samuels was exposed to the institutional approach already during his undergraduate days at Miami, and he pursued the Ph.D. at Wisconsin because of its institutionalist tradition (then drawing to a close), as evidenced in faculty members such as Edwin Witte, Harold Groves, Martin Glaeser, Kenneth Parsons, and Robert Lampman. -

Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning

MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC PLANNING REPUBLIC OF GHANA SECTOR M&E PLAN MONITORING AND EVALUATION PLAN For MOFEP MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2010-2013) Under THE GHANA SHARED GROWTH AND DEVELOPEMNT AGENDA (GSGDA) 2010 – 2013 APRIL 2011 MOFEP M&E Plan DRAFT Page | 1 TABLE OF CONTENT LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................... 3 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................ 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Goal and Objectives of the MOFEP’s Sector Medium Term Development Plan (SMTDP) ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Implementation Status of the MTDP .............................................................................. 12 1.4 Purpose of MOFEP M&E Plan ........................................................................................ 14 1.5 Structure of this M&E Plan .............................................................................................. 16 CHAPTER TWO ............................................................................................................. 17 2.0 MONITORING AND EVALUATION ACTIVITIES ..................................... -

Oligopoly, Regional Development and the Political Economy of Separatism

OLIGOPOLY, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF SEPARATISM - with a case study of the United Kingdom and Scotland - By IVAN RAJIĆ Darwin College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Centre of Development Studies, University of Cambridge Date of Submission: December, 2017 OLIGOPOLY, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF SEPARATISM - with a case study of the United Kingdom and Scotland - IVAN RAJIĆ The present thesis aims to increase our understanding of the causes of separatism. The inspiration for this topic comes from the fact that separatist conflicts can become extremely destructive, and thus a better understanding of why they emerge may help us prevent much human suffering by pointing to ways in which separatism can be avoided. More specifically, the thesis aims to explain the link between separatism and regional development disparities. The argument presented is that inter-regional economic conflicts (such as about inter-regional fiscal redistribution) easily emerge between regions at different levels of development, and that under certain conditions, particularly prolonged recessions and austerity, such conflicts can become an important driver of separatist aspirations. This can happen in both poorer and richer regions. The thesis further argues that this entire process can only be fully understood if we analyse society through a class prism. Given that regional development disparities often lie at the root of inter-regional economic conflicts, one of the ways of avoiding such conflicts – and thus also separatism – would be to equalize regional development levels. In order to do so, however, we first need to understand why regional disparities emerge and persist. -

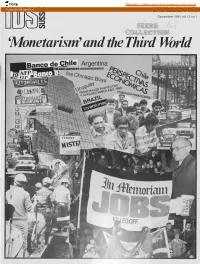

'Monetarism'and the Third World

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by IDS OpenDocs BULLETIN C/3 ^ D ecem ber 1981 vol 13 no 1 3 A f t n f k A pT C/3 ‘Monetarism’and the Third World de Chile Argentina ■ tra b a ja d o re s iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii RUT0MQV1LES moTocia-ETRS COMP&NIA Of SIG-L U FENIX PERU TERNOS ‘Monetarism’: its effects on developing countries editors: Stephany Griffith-Jones and Dudley Seers CONTENTS pages Foreword 1 Dudley Seers Editorial 3 Stephany Griffith-Jones Latin American Monetarism in Crisis 6 David Felix Monetarism in the UK and the Southern Cone: an Overview 14 John Wells The New Recycling: Economic Theory, IMF Conditionality and Balance 27 of Payments Adjustment in the 1980s Philip Daniel The New Leviathan: the Chicago School and the Chilean Regime 1973-80 38 Philip O'Brien Recent Experiences of Stabilisation: Argentina s Economic Policy 51 1976-81 Luis Beccaria and Ricardo Carciofi What Happens to Economic Growth when Neo-Classical Policy 60 Replaces Keynesian? The Case of South Korea Tony Michell Consumerism and the New Orthodoxy in Latin America 68 Carlos Filgulera BOOK REVIEWS Two reviews of Bela Balassa's The Newly Industrialising Countries in the World Economy I Re-thinking de-linking 74 Geoff Lamb II Do outward-looking policies really work? 75 A. I. MacBean Notes on Contributors SUMMARY Stephany Griffith-Jones is a Research Officer of the Latin American Monetarism in Crisis Institute of Development Studies. She worked in the David Felix Central Bank of Chile for several years, and has written This article discusses the basic features of monetarist thinking, stressing the differences between their application to advanced capitalist countries a number of articles on international finance and on and the semi-industrialised Latin American economies. -

Mill, Liberty and the Facts of Life

UC Berkeley Working Papers Title Mill, Liberty And The Facts Of Life Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/26n9r19s Authors Stimson, Shannon C. Milgate, Murray Publication Date 2001 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MILL, LIBERTY AND THE FACTS OF LIFE Shannon C. Stimson University of California, Berkeley and Murray Milgate Queens’ College, Cambridge Working Paper 2001-2 Working Papers published by the Institute of Governmental Studies provide quick dissemination of draft reports and papers, preliminary analysis, and papers with a limited audience. The objective is to assist authors in refining their ideas by circulating results and to stimulate discussion about public policy. Working Papers are reproduced unedited directly from the author’s page. MILL, LIBERTY AND THE FACTS OF LIFE Shannon C. Stimson University of California, Berkeley and Murray Milgate Queens’ College, Cambridge Working Paper 2001-2 Abstract: This paper examines John Stuart Mill's discussion of economic liberty and individual liberty, and his view of the relationship between the two. It explores how, and how effectively, Mill developed his arguments about the two liberties; reveals the lineages of thought from which they derived; and considers how his arguments were altered by political economists not long after his death. It is argued that the distinction Mill drew between the two liberties provided him with a framework of concepts which legitimised significant government intervention in economic matters without restricting individual liberty. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank, without in any way implicating, the following individuals for their helpful criticisms and suggestions on earlier drafts of this essay: Robert Adcock, Mark Bevir, Colin Bird, Alan Houston, Michael Rogin, Ian Shapiro.