Kierkegaard's View of Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Modern Philosophy) Part I: Fichte to Hegel 9. Walter Benjamin, Der

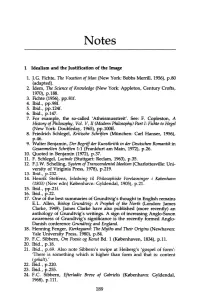

Notes 1 Idealism and the Justification of the Image 1. J.G. Fichte, The Vocation of Man (New York: Bobbs Merrill, 1956), p.80 (adapted). 2. Idem, The Science of Knowledge (New York: Appleton, Century Crofts, 1970), p.188. 3. Fichte (1956), pp.81f. 4. Ibid., pp.98f. 5. Ibid., pp.124f. 6. Ibid., p.147. 7. For example, the so-called 'Atheismusstreit'. See: F. Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Vol. V, II (Modern Philosophy) Part I: Fichte to Hegel (New York: Doubleday, 1965), pp.lOOff. 8. Friedrich Schlegel, Kritische Schriften (Miinchen: Carl Hanser, 1956), p.46. 9. Walter Benjamin, Der Begriff der Kunstkritik in der Deutschen Romantik in Gesammelten Schriften 1:1 (Frankfurt am Main, 1972), p.26. 10. Quoted in Benjamin (1972), p.37. 11. F. Schlegel, Lucinde (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1963), p.35. 12. F.J.W. Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism (Charlottesville: Uni versity of Viriginia Press, 1978), p.219. 13. Ibid., p.232. 14. Henrik Steffens, Inledning til Philosophiske Forelasninger i K9benhavn (1803) (New edn) K0benhavn: Gyldendal, 1905), p.21. 15. Ibid., pp.21f. 16. Ibid., p.22. 17. One of the best summaries of Grundtvig's thought in English remains E.L. Allen, Bishop Grundtvig: A Prophet of the North (London: James Clarke, 1949). James Clarke have also published (more recently) an anthology of Grundtvig's writings. A sign of increasing Anglo-Saxon awareness of Grundtvig's significance is the recently formed Anglo Danish conference Grundtvig and England. 18. Henning Fenger, Kierkegaard: The Myths and Their Origins (Newhaven: Yale University Press, 1980), p.84. 19. -

"A Human Being's Highest Perfection": the Grammar and Vocabulary of Virtue in Kierkegaard's Upbuilding Discourses

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 33 Issue 3 Article 4 7-1-2016 "A Human Being's Highest Perfection": The Grammar and Vocabulary of Virtue in Kierkegaard's Upbuilding Discourses Pieter H. Vos Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Vos, Pieter H. (2016) ""A Human Being's Highest Perfection": The Grammar and Vocabulary of Virtue in Kierkegaard's Upbuilding Discourses," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 33 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil201661461 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol33/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. “A HUMAN BEING’S HIGHEST PERFECTION”: THE GRAMMAR AND VOCABULARY OF VIRTUE IN KIERKEGAARD’S UPBUILDING DISCOURSES Pieter H. Vos Focusing on the grammar and vocabulary of virtue in Kierkegaard’s upbuilding works, it is argued that the Danish philosopher represents a Christian conception of the moral life that is distinct from but—contrary to Alasdair MacIntyre’s claim—not completely opposed to Aristotelian and Thomistic virtue ethics. Although the realities of sin and salvation transcend virtue ethics based purely on human nature, it is demonstrated that this does not prevent Kierkegaard from speaking constructively about human nature, its teleology (a teleological conception of the self) and about the virtues. -

Nietzsche and the Pathologies of Meaning

Nietzsche and the Pathologies of Meaning Jeremy James Forster Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Jeremy James Forster All rights reserved ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE AND THE PATHOLOGIES OF MEANING Jeremy Forster My dissertation details what Nietzsche sees as a normative and philosophical crisis that arises in modern society. This crisis involves a growing sense of malaise that leads to large-scale questions about whether life in the modern world can be seen as meaningful and good. I claim that confronting this problem is a central concern throughout Nietzsche’s philosophical career, but that his understanding of this problem and its solution shifts throughout different phases of his thinking. Part of what is unique to Nietzsche’s treatment of this problem is his understanding that attempts to imbue existence with meaning are self-undermining, becoming pathological and only further entrenching the problem. Nietzsche’s solution to this problem ultimately resides in treating meaning as a spiritual need that can only be fulfilled through a creative interpretive process. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I: The Birth of Tragedy and the Problem of Meaning 30 Part I: Background 33 Part II: Meaningfulness in Artistic Cultures 45 Part III: Meaningfulness in Tragic Cultures 59 Part IV: Meaningfulness in Socratic Cultures 70 Conclusion: The Solution to Socratism 78 Chapter II: Meaning, Science, and the “Perceptions of Science -

Soren Kierkegaard

For M.A;Semester-3 Contemporary Western Philosophy By Dr. Vijeta Singh Assistant Professor University Department of Philosophy(P.U) Soren Kierkegaard Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), considered to be the first existentialist philosopher, was of Danish nationality. He was also a theologian, poet, social critic and religious author. Accordingly, his work crosses the boundaries of philosophy, theology, psychology, literary criticism, devotional literature and fiction. He made many original conceptual contributions to each of the disciplines he employed. He was a great supporter of freedom and values of human individual. The main philosophical themes and principal conceptions of Kierkegaard’s philosophy are truth, freedom, choice, and God. For him, human beings stand out as responsible individuals who must make free choices. Kierkegaard was born on May 5, 1813 in Copenhagen, Denmark. He studied Theology and Philosophy from Copenhagen University . Kierkegaard lived the majority of his life alone. He left his native Copenhagen only three or four times, each time to visit Berlin , and never married, though he was engaged for a short time. Kierkegaard is known for his critiques of Hegel, for his fervent analysis of the Christian faith, and for being an early precursor to the existentialists. He is known as the “father of existentialism”. Kierkegaard is generally considered to have been the first existentialist philosopher, though he did not use the term existentialism. He proposed that each individual , not society or religion, is solely responsible for giving meaning to life and living it passionately and sincerely, or authentically. Kierkegaard is said to have inaugurated modern existentialism in the early 19th century, while Jean-Paul Sartre is said to have been the last great existentialist thinker in the 20th century. -

Temporality and Historicality of Dasein at Martin Heidegger

Sincronía ISSN: 1562-384X [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara México Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Javorská, Andrea Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Sincronía, no. 69, 2016 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=513852378011 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Filosofía Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Andrea Javorská [email protected] Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Eslovaquia Abstract: Analysis of Heidegger's work around historicity as an ontological problem through the existential analytic of Being Dasein. It seeks to find the significant structure of temporality represented by the historicity of Dasein. Keywords: Heidegger, Existentialism, Dasein, Temporality. Resumen: Análisis de la obra de Heidegger en tornoa la historicidad como problema ontológico a través de la analítica existencial del Ser Dasein. Se pretende encontrar la estructura significativa de temporalidad representada por la historicidad del Dasein. Palabras clave: Heidegger, Existencialismo, Dasein, Temporalidad. Sincronía, no. 69, 2016 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Martin Heidegger and his fundamental ontology shows that the question Received: 03 August 2015 Revised: 28 August 2015 of history belongs among the most fundamental questions of human Accepted: -

Existential Aspect of Being: Interpreting J. P. Sartre's Philosophy

Existential aspect of Being: Interpreting J. P. Sartre’s Philosophy Ivan V. Kuzin, Alexander A. Drikker & Eugene A. Makovetsky Saint Petersburg State University, Russia Abstract The article discusses rationalistic and existential approaches to the problem of existence. The comparison of Sartre's pre-reflective cogito and Descartes' reflective cogito makes it possible to define how Sartre’s thought moves from the thing to consciousness and from consciousness to the thing. At the same time, in Being and Nothingness Sartre does not only define the existence of the thing in its passivity—which in many respects corresponds to Descartes' philosophy, but also as an open orientation towards consciousness, the latter concept not being fully developed by him. This statement may be regarded as a hidden component of Sartre’s key thesis about the role of the Other in the verification of our existence. The most important factor in understanding this is the concept of the look. Detailed analysis of Sartre’s theses in Being and Nothingness enables us to demonstrate that the concept of the look makes it possible to consider the identity of being-in-itself and being-for-itself (consciousness). Keywords: Sartre, rationalism, existentialism, thing, being, the look, existence, nothingness, consciousness, the Other 1. Introduction E. Husserl said that being of the object is such “that it is cognisable in itself” (“daß es in seinem Wesen liegt, erkennbar zu sein”). (Ingarden 1992: 176) This statement is important if we are to accept the fact that the possibility of looking at the object correlates with being of the object itself. -

The Search for Meaning of Life: Existentialism, Communication, and Islam

The Search for 0eaning of Life: Existentialism, Communication, and ,slam 2. HasEiansyah ABSTRACT 0aNna merupaNan hal sangat penting dalam Nehidupan manusia. Tanpa maNna, Nehidupan aNan tanpa arah dan penuh Negelisahan. 0aNna hidup dapat dicari melalui nilai-nilai Nreatif, nilai-nilai pengalaman, nilai-nilai cara EersiNap, NomuniNasi dan partisipasi, pemahaman diri, dan pemahaman aNan aMaran agama. ,slam menawarNan aspeN nomatif Eagi pencapaian hidup EermaNn lewat pemEersihan diri, Nontemplasi, serta Nomitmen pada Neilmuan dan NemasyaraNatan. ,ntroduction was ever upset deeply, while he had a good posi- tion and future. He needed something else, that :e face our life every day. :e sleep, wake was a high meaningful life, which could make him up, eat, work, take part in communication, have a aEsolutely satisfied. He gave up all his position. rest, and so on. Events come to us and we pay Then, he was lost himself in a realm of mysticism attention to them, even involve ourselves in them, (tashawwuf). In this world, he felt a highest satis- or ignore them. In other cases, we need some- faction and a real significant life. thing, we seek it, we get it or not, then we feel At first glance it seems difficult to understand happy or sad. It takes place automatically and why, for instance, someone is very interested in routinely. :e are as though in a circle of situation. climEing up mountain, while another is pleased to However in reality, life is not as simple as that. contriEute most of his possession to others and Each of us is not always involved passively in a he chooses to lead an extremely soEer life. -

A Selected Glance at How Kierkegaard Stages the Problem of What It Is to Become a Christian in His Initial Aesthetic Authorship

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1970 A selected glance at how Kierkegaard stages the problem of what it is to become a Christian in his initial aesthetic authorship. Frank Schloegel University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Schloegel, Frank, "A selected glance at how Kierkegaard stages the problem of what it is to become a Christian in his initial aesthetic authorship." (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6627. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6627 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. -

IN SEARCH of AUTHENTICITY: from Kierkegaard to Camus 1

In Search of Authenticity ‘This man has, I repeat, no place in a community whose basic principles he flouts without compunction…’. I tried to explain that it was because of the sun, but I was only too conscious that it sounded nonsensical… I explained that I didn’t believe in God… I told him that I wasn’t conscious of any ‘sin’; all I knew was that I’d been guilty of a criminal offence… In Camus’s The Outsider, Meursault’s struggle with authenticity leads to his being judged more than just a criminal. Other fictional heroes, or anti-heroes, have been created by philosophers to explore certain ideas or theories: like Meursault, Kierkegaard’s Abraham, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Sartre’s Mathieu all embody the contradictions of trying to live outside society’s accepted norms. Jacob Golomb’s In Search of Authenticity examines these characters in his analysis of the ethics of authenticity. His own passionate commitment to the quest for such an ideal is clearly evident in his writing. Golomb is particularly concerned that postmodernism devalues the subjectivity and pathos that inextricably link an individual’s search for authenticity. He argues that this search is now all the more pertinent and relevant when set against the general disillusionment characterizing the mood of the late twentieth century. In Search of Authenticity provides invaluable insight into the heroes and anti-heroes of the great Continental philosophers. Like them it marries philosophy and literature by looking at the rational model of ethics compared with the romantic ideal of authenticity. Consequently, it will prove vital reading for students of both philosophy and literature. -

Kierkegaard on Indirect Communication, the Crowd, and a Monstrous Illusion Antony Aumann Northern Michigan University, [email protected]

Northern Michigan University The Commons Faculty Works 2010 Kierkegaard on Indirect Communication, the Crowd, and a Monstrous Illusion Antony Aumann Northern Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.nmu.edu/facwork Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Esthetics Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Antony Aumann, “Kierkegaard on Indirect Communication, the Crowd, and a Monstrous Illusion,” in Robert L. Perkins (ed.), International Kierkegaard Commentary: Point of View (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2010) 295-324. This Conference Paper in Published Proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by The ommonC s. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of The ommonC s. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Kierkegaard on Indirect Communication, the Crowd, and a Monstrous Illusion Antony Aumann One thing that continues to attract people to Kierkegaard’s writings is his inexhaustible literary creativity. Unlike many thinkers, he does not express his philosophical insights in straightforward academic prose. He delivers them to us under pseudonyms, through narratives, and in an ironic or humorous style. Even in his seemingly straightforward works, we find trickery and “profound deception.”1 Part of what makes Kierkegaard’s literary style of philosophical interest is the theory that lies behind it, his so-called “theory of indirect communication.” The most exciting and provocative aspect of the theory concerns the alleged importance of indirect communication. In several places throughout Kierkegaard’s writings we find the claim that there are some ends only indirect communication can accomplish—a claim not meant to entail the guaranteed success of indirect communication, only its ability to do what direct communication cannot. -

Kierkegaard And/Or Catholicism: a Matter of Conjunctions Center for Catholic Studies, Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Center for Catholic Studies Faculty Seminars and Center for Catholic Studies Core Curriculum Seminars 2008 Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A Matter of Conjunctions Center for Catholic Studies, Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-studies Part of the Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Center for Catholic Studies, Seton Hall University, "Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A Matter of Conjunctions" (2008). Center for Catholic Studies Faculty Seminars and Core Curriculum Seminars. 14. https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-studies/14 Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Center for Catholic Studies Faculty Seminars Proceedings Summer 2008 Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A Matter of Conjuctions Center for Catholic Studies, Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.shu.edu/summer-seminars Part of the Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Center for Catholic Studies, Seton Hall University, "Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A Matter of Conjuctions" (2008). Center for Catholic Studies Faculty Seminars. Paper 4. http://scholarship.shu.edu/summer-seminars/4 ―Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A Matter of Conjuctions‖ 2008 Summer Seminar Center for Catholic Studies Seton Hall University CENTER FOR CATHOLIC STUDIES Faculty Summer Seminar 2008 ―Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A Matter of Conjunctions‖ Facilitator: William Cahoy Dean, School of Theology and Seminary, Saint John’s University May 20-22 (8:30 am to 12:00 pm) “Kierkegaard and/or Catholicism: A matter of conjunctions” It is often said (accurately) that one of the distinguishing marks of a Catholic understanding of life is its both-and approach in contrast to the either-or approach more characteristic of a Protestant sensibil- ity. -

Søren Kierkegaard Newsletter 47

CONTENTS Page NEWS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS ARTICLE The Joy of Kierkegaard By Hugh S. Pyper REVIEWS 1st Glauben wiederholbar? Derrida liest Kierkegaard by Tilman Bey rich By Heiko Schuiz Upbuilding Discourses: Philosophy, Literature, and Theology by George Pattison Reviewed by David D. Possen Editor: Gordon Marino Number 47 Associate Editors: Jamie Lorentzen, John Poling and February, 2004 David Possen Assistant Editor: Cynthia Wales Lund Managing Editor: Cleo N. Granneman , SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS DANISH COURSE, SUMMER 2004 The Kierkegaard Library will offer a month-long intensive Danish course this summer June 28 - July 23. Sinead Ladegaard Knox from Copenhagen will be the instructor. If you are interested, please email Gordon Marino immediately at marino@,stolaf.edu. Class size is limited to the first scholars who apply. SUMMER FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM 2004 Summer fellowships for research in residence are offered to scholars for use of the collection between June 1 and November 15. The awards include campus housing and a $250 per month stipend. Scholarships are available at other times of year also. Please contact Gordon Marino immediately if you are interested in the 2004 program. 5"' International Kierkegaard Conference June 11-15,2005 CALL FOR PAPERS The Hong Kierkegaard Library will host its 5thInternational Conference June 11-15,2005 at St. Olaf College. The theme of the conference will be "Kierkegaard's Journals and Notebooks." Professor George Pattison of Oxford University will offer the keynote address. Papers are to have a reading length, which will be strictly applied, of 20 minutes. We are also planning to hold a dissertation panel discussion in which scholars who are in the process of writing or who have just completed their dissertations will summarize their research.