Lal Ded and Her Spiritual Journey S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page8.Qxd (Page 1)

SATURDAY, AUGUST 27, 2016 DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU daily Excelsior Kashmir rebellion Celebrate Established 1965 Founder Editor S.D. Rohmetra Then and Now Indian girl power ! Amit Kushari (IAS Retd) urban Kashmiris, were dream- nities and not God of only world. No body wants to ing about azaadi and mostly Muslims). Allah is the God of employ or rent out an accommo- Shahnaz Husain Paddar sapphire hen the first Kashmir they were 90% sure that azaadi Pandits also and when they were dation to a Muslim. After rebellion broke out in 016 is the year of Indian Girl Power! Girls have made India ndoubtedly, industries sector in the State has was round the corner. In May running away with tears in their Osama Bin Laden was caught W1990/91 the situation 1991, when the winter secretari- eyes, Allah must have been red handed in Pakistan, the USA proud at Rio, bringing home Olympic medals, along with the lagged far behind in making a valuable con- was very, very grim at that time at at Jammu was shifting to extremely annoyed with the and the entire Western world is 2assurance that our girls can match up to the world’s best. Sak- tribution towards the economic development also and J&K had to remain Srinagar for the summer, many Muslims and He must have now hesitant to speak up for shi won the bronze in wrestling, a so-called male domain. Sindhu U under President's rule for six of the State. This area has been a victim of negli- Kashmiri employees withdrew withheld the order granting Muslims. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Lalleshwari-Poems

Classic Poetry Series Lalleshwari - 100 poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: PoemHunter.Com - The World's Poetry Archive Lalleshwari (1320 – 1392) Lalleshwari (््््््््््) (1320–1392), also known as Lalla, Lal Ded or "Lal Arifa".She was a mystic of the Kashmiri Shaivite sect, and at the same time, a Sufi saint. She is a creator of the mystic poetry called vatsun or Vakhs, literally 'speech'. Known as Lal Vakhs, her verses are the earliest compositions in the Kashmiri language and are an important part in history of Kashmiri literature. Lal Ded and her mystic musings continue to have a deep impact on the psyche of Kashmiri common man, and the 2000 National Seminar on her held at New Delhi led to the release of the book Remembering Lal Ded in Modern Times. A solo play in English, Hindi and Kashmiri titled 'Lal Ded' (based on her life), has been performed by actress Mita Vashisht all over India since 2004. Biography Lalleshwari was born in Pandrethan (ancient Puranadhisthana) some four and a half miles to the southeast of Srinagar in a Kashmiri Pandit family. She married at age twelve, but her marriage was unhappy and she left home at twenty-four to take sanyas (renunciation) and become a disciple of the Shaivite guru Siddha Srikantha (Sed Bayu). She continued the mystic tradition of Shaivism in Kashmir, which was known as Trika before 1900. There are various stories about Lal Ded's encounters with the founding fathers of Kashmiri Sufism. One story recounts how, when Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani (Nund Rishi) was born, he wouldn’t feed from his mother. -

Pok Oct 2015

POK Volume 8 | Number 10 | October 2015 News Digest A MONTHLY NEWS DIGEST ON PAKISTAN OCCUPIED KASHMIR Compiled & Edited by Dr Priyanka Singh Dr Yaqoob-ul Hassan Political Developments Opening the Kargil-Skardu Road For 'Kashmir Cause': AJK lawmakers Want Blue Passports Pakistan's Kashmir Policy and Options of Kashmiri Nationalists PM Approves Ex-Justice Munir as CEC of AJK PM Nawaz Inaugurates Pak-China Friendship Tunnels Over Attabad Lake MPC Calls for AJK-like Governance System for GB 27 Afghan-owned Shopping Centers Sealed Former Terrorist Hashim Qureshi Backs Protests in PoK, Says Pakistani Forces are no Better Than British Colonialists Economic Developments Cross LOC Energy Potential New Strategy: AJK Govt to Revive Industries All Set for the Ground Breaking of 100 MW Gulpur Power Project Govt Considering Financing Options for Bhasha Dam Project International Developments US Renews Support for Bhasha Dam, Renewable Energy Projects China has Established its Presence Across PoK Gilgit Baltistan: Womens' Rights Violations Raised at UN Human Rights Council Other Developments Water in AJK Homebound: A Life Less Ordinary No. 1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg New Delhi-110 010 Jammu & Kashmir (Source: Based on the Survey of India Map, Govt of India 2000 ) In this Edition The proposal on opening the Kargil-Skardu route as part of the cross Line of Control confidence building measures between India and Pakistan has been on the table for long. However, till date not much progress has been made on this front. Since the LoC was opened up for movement of goods and people across both sides, at one point each in the Jammu sector and the valley, there have been high hopes amongst people in the Ladakh sector that the link between Kargil and Skardu gets materialized. -

Kashmir Shaivism Pdf

Kashmir shaivism pdf Continue Trident (trishalabija mashalam), symbol and Yantra Parama Shiva, representing the triadic energies of the supreme goddess Para, Para-apara and Apara Sakti. Part of a series onShaivism DeitiesParamashiva(Supreme being) Shiva Sadasiva Bhairava Rudra Virabhadra Shakti Durga Kali Parvati Sati Ganesha Murugan Sastha Shiva forms Others Scriptures and texts Vedas Upanishads (Svetasvatara) Agamas and Tantras Shivasutras Tirumurai Vachanas Philosophy Three Components Pati Pashu Pasam Three bondages Anava Karma Maya 36 Tattvas Yoga Satkaryavada Abhasavada Svatantrya Aham Practices Vibhuti Rudraksha Panchakshara Bilva Maha Shivaratri Yamas-Niyamas Guru-Linga-Jangam Schools Adi Margam Pashupata Kalamukha Kapalika Mantra Margam Saiddhantika Siddhantism Non - Saiddhantika Kashmir Shaivism Pratyabhijna Vama Dakshina Kaula: Trika-Yamala- Kubjika-Netra Others Nath Inchegeri Veerashaiva/Lingayatism Siddharism Sroutaism Aghori Indonesian Scholars Lakulisha Abhinavagupta Vasugupta Utpaladeva Nayanars Meykandar Nirartha Basava Sharana Srikantha Appayya Navnath Related Nandi Tantrism Bhakti Jyotirlinga Shiva Temples vte Part of a series onShaktism Deities Adi Parashakti (Supreme) Shiva-Shakti Parvati Durga Mahavidya Kali Lalita Matrikas Lakshmi Saraswati Gandheswari Scriptures and texts Tantras Vedas Shakta Upanishads Devi Sita Tripura Devi Bhagavatam Devi Mahatmyam Lalita Sahasranama Kalika Purana Saundarya Lahari Abhirami Anthadhi Schools Vidya margam Vamachara Dakshinachara Kula margam Srikulam Kalikulam Trika Kubjikamata Scientists Bhaskararaya Krishnananda Agamawagisha Ramprasad Sen Ramakrishna Abhirami Bhattar practices yoga Yoni Kundalini Panchamakara Tantra Yantra Festivals and temples Navaratri Durga Puja Lakshmi Puja Puja Saraswati Puj more precisely, Trika Shaivism refers to the non-dual tradition of the ziva-Sakta Tantra, which originated sometime after 850 AD. The defining features of The Trika tradition are its idealistic and monistic philosophical system Pratyabhija (Recognition), founded by Utpaladeva (c. -

Pakistan-Azad Jammu and Kashmir Politico-Legal Conflict Sep 2011

Background Paper Pakistan-Azad Jammu & Kashmir Politico-Legal Conflict September 2011 Background Paper Pakistan-Azad Jammu & Kashmir Politico-Legal Conflict September 2011 PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright© Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency PILDAT All Rights Reserved Printed in Pakistan Published: September 2011 ISBN: 978-9696-558-232-9 Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to PILDAT Published by Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency - PILDAT Head Office: No. 7, 9th Avenue, F-8/1, Islamabad, Pakistan Lahore Office: 45-A, Sector XX, 2nd Floor, Phase III Commercial Area, DHA, Lahore Tel: (+92-51) 111-123-345; Fax: (+92-51) 226-3078 E-mail: [email protected]; Web: www.pildat.org PILDAT BACKGROUND PAPER Pakistan-AJ&K Politico-Legal Conflict CONTENTSCONTENTS Foreword 05 Profile of the Author 07 Introduction 09 Structure and Context of the Paper 10 The Politico-Legal Status of AJ&K 10 Evolved Territorial Configuration of AJ&K 12 Genesis of Conflicted Relationship 13 Contemporary Contentious Issues 17 Conclusion 18 Map: State of Jammu and Kashmir 11 PILDAT BACKGROUND PAPER Pakistan-AJ&K Politico-Legal Conflict FOREWORD he Background Paper on Pakistan-Azad Jammu & Kashmir Politico-Legal Conflict has been commissioned by PILDAT to Tassist and support an informed dialogue on the legal and political conflict between the State of Pakistan and AJ&K. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Dina Nath Kaul 'Nadim' the ‘Gentle Colossus’ of Modern Kashmiri Literature Onkar Kachru HIMALAYAN and CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 8 No.1 January - March 2004 NADIM SPECIAL Deodar in a Storm: Nadim and the Pantheon Braj B. Kachru Lyricism in Nadim’s Poetry T.N. Dhar ‘Kundan’ Nadim – The Path Finder to Kashmiri Poesy and Poetics P.N. Kachru D.N. Kaul ‘Nadim’ in Historical Perspective M.L. Raina Dina Nath Kaul 'Nadim' The ‘Gentle Colossus’ of Modern Kashmiri Literature Onkar Kachru HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K. WARIKOO Guest Editor : RAVINDER KAUL Assistant Editor : SHARAD K. SONI © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 100.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 400.00 Institutions : Rs. 500.00 & Libraries (Annual) OVERSEAS (AIRMAIL) Single Copy : US $ 5.00 UK £ 7.00 Annual (Individual) : US $ 30.00 UK £ 20.00 Institutions : US $ 50.00 & Libraries (Annual) UK £ 35.00 The publication of this journal (Vol.8, No.1, 2004) has been financially supported by the Indian Council of Historical Research. The responsibility for the facts stated or opinions expressed is entirely of the authors and not of the ICHR. -

Paramahamsa Nithyananda

38 2010-05-06 The New Indian Express negatively stereotypes Hindu Spiritual Leaders and denounces Sanatana Hindu Dharma After months of poisonous defamation by the media mafia on His Divine Holiness, The New Indian Express goes on to ‘incite hatred’, intolerance and ethical discrimination against Hindu Gurus. It categorically declares the intended result: the illegitimization of Sanatana Hindu Dharma and negatively stereotyping the Hindu Spiritual Leaders (Gurus) in Hindu community across the globe. 06 May 2010: A yellow journalist of The New Indian Express writes an article dehumanizing His Divine Holiness Paramahamsa Nithyananda. It is not a coincidence to see several atrocious articles against His Divine Holiness come out on The Indian Express. It must be recalled that The Indian Express is not just another newspaper. The Indian Express is one of the main mediums that S. Gurumurthy used to dehumanize and persecute His Divine Holiness Paramahamsa Nithyananda. Yellow journalist Vasanth Kannabiran uses a perverted lies to incite hatred and justifies the inhumane treatment and human rights violation on Him. - Media repeatedly peddled the obvious falsehoods – denying the systematic persecution of Hindu Gurus; discarding their spiritual legitimacy to program that they are unworthy of the reverence from the Hindu community. - This slanderous article weaves several themes to demonize Hinduism and Hindu Gurus. Fact What was written in What it wants reader to news article believe - faulty generalization Lord Hanuman is highly Lord Hanuman wears The author justifies it’s revered deity in Sanatana underwear atrocious content claiming Hindu Dharma that because of the fabricated footage of His 39 Lord Ganesha, the Lord Ganesha wears Divine Holiness, society worshipped Hindu deity son pantyhose will stop respecting of Lord Shiva Hanuman and Ganesh due to faulty generalization. -

Dubious Cash Transitions in JK Under IT Dept Scanner

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com Volthe No: XXI|Issue No. 300northlines | 20.12.2016 (Tuesday) |Daily | Price ` 2/-| Jammu Tawi | Pages-12 |Regd. No. JK|306|2014-16 Justice Khehar Yet another curb on old note Dubious cash transitions in appointed CJI deposits exceeding Rs 5,000 NL CORRESPONDENT JK under IT Dept scanner NEW DELHI, DEC 19 The Reserve Bank on 'Action against tax defaulters after Dec 31' Monday imposed stiff restrictions on depositing NL CORRESPONDENT who are suspected of more than Rs 5,000 in the SRINAGAR, DEC 19 facilitating bulk and improper exchange of old scrapped Rs 500 and Rs The Income Tax department currency notes with large 1,000 notes, mandating that Monday said that they are quantities of new currency it could be deposited only closely watching the notes. Officials are also once per account till doubtful cash transitions in aware of some sort of nexus December 30, that too after "It has been decided to only once per account till NL CORRESPONDENT Jammu and Kashmir and being run in Jammu and explaining to bank officials NEW DELHI, DEC 19 place certain restrictions on Dec 30 that many people are under Srinagar for exchanging old the reasons for not having deposits of SBNs into bank - After showing reasons for scanner, against whom the currency with news done that so far. Justice Jagdish Singh accounts while encouraging not doing so earlier details are being collected. currency on 10-15 per cent Stipulating that restrictive Khehar, the second senior the deposits of the same - After questioning on "We have decided to take commission in the market conditions would also apply against whom the details be taken against them as per most judge of the Supreme under the Taxation and record, in the presence of at action against tax defaulters also. -

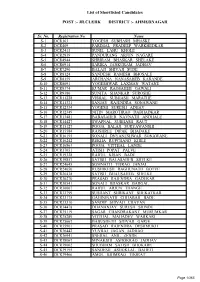

Jr.Clerk District :- Ahmednagar

List of Shortlisted Candidates POST :- JR.CLERK DISTRICT :- AHMEDNAGAR Sr. No. Registration No. Name S-1 DCR163 YOGESH SUBHASH MHASKE S-2 DCR469 PARIMAL PRADEEP WARKHEDKAR S-3 DCR2413 SUNIL LAHU KHOLE S-4 DCR2839 PANDURANG ARJUN NAGARE S-5 DCR4944 SHRIRAM BHASKAR SHELAKE S-6 DCR6914 SARIKA JANKURAM JADHAV S-7 DCR7290 BALAJI SHIVAJI SUDE S-8 DCR8124 SANDESH RAMESH BHOSALE S-9 DCR8159 ARCHANA NANASAHEB KARANDE S-10 DCR8691 YOGESHWAR LAXMAN WATANE S-11 DCR9374 KUMAR RAOSAHEB GAWALI S-12 DCR9386 SUNITA SHANKAR SUROSHE S-13 DCR11228 VISHAL SUBHASH MARATHE S-14 DCR11331 SANJAY RAJENDRA SONAWANE S-15 DCR12334 YOGESH SURESH ADHAV S-16 DCR12349 NITIN MAROTIRAO DABHADKAR S-17 DCR13481 BABASAHEB NAVNATH ANDHALE S-18 DCR14427 SWAPNAL SUBHASH RAUT S-19 DCR15127 POOJA BALAJI SURYAWANSHI S-20 DCR15584 RAJSHREE DIPAK BHADAKE S-21 DCR16195 SONALI DNYANESHWAR SONAWANE S-22 DCR16242 REKHA RUPCHAND KHILE S-23 DCR16863 POOJA VITTHAL LANDE S-24 DCR17651 ATISH POPAT PALVE S-25 DCR19328 RAHUL KISAN BADE S-26 DCR19857 SATISH BALASAHEB SHELKE S-27 DCR24645 SOMNATH TEJRAO JANJAL S-28 DCR24650 RUSHIKESH RAGHUNATH BOTVE S-29 DCR26438 SATISH BHAUSAHEB SHELKE S-30 DCR30270 PRASAD RAJENDRA GADEKAR S-31 DCR30541 SONALI BHASKAR BARGAL S-32 DCR30667 RAHUL ARJUN THANGE S-33 DCR32799 SUSHANT SHRIKANT SHEKATKAR S-34 DCR33175 GAHININATH CHHABAJI BADE S-35 DCR33310 SANDIP SHIVAJI CHAVAN S-36 DCR34478 DHANANJAY SURESH SHINDE S-37 DCR35119 SAGAR CHANDRAKANT MURUMKAR S-38 DCR35289 VITTHAL MAHADEV WARKARI S-39 DCR35667 BABUSHETH SHIVAJI GARJE S-40 DCR35901 PRASAD RAJENDRA DESHMUKH S-41 DCR36442 YUVRAJ JAGAN JADHAO S-42 DCR36941 SNEHAL ANIL ZENDE S-43 DCR38067 MINAKSHI ASHOKRAO JADHAV S-44 DCR39062 SHUBHAM SATISH BHOKARE S-45 DCR39195 SANDESH ASHOKLAL BAHETI S-46 DCR39466 AMOL BHIMRAO THORAT Page 1/365 List of Shortlisted Candidates POST :- JR.CLERK DISTRICT :- AHMEDNAGAR Sr. -

Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (Pok), Referred As ‘Azad Kashmir’ and ‘Gilgit-Baltistan’ by the Government of Pakistan

POK NEWS DIGEST A MONTHLY NEWS DIGEST ON PAKISTAN OCCUPIED KASHMIR Volume 3 Number 2 February 2010 • Commentary Leadership Crisis in Gilgit-Baltistan - Senge Hasnan Sering • Political Developments 10 Killed, 81 Hurt in Muzaffarabad Blast, PM Announces Aid for Muzaffarabad Blast Victims 10 Injured as Bomb Explodes While Being Diffused in PoK Army to Train AJK Police in Fighting Terrorism KNP Concerned Over Growing Extremism PAK • Economic Developments AJK Council’s Indecision Costs Govt Rs11m BISP to End Quota System in Gilgit-Baltistan: Farzana Raja LoC Trade Resumes Following Assurance • International Developments Pakistan Senators Delegation Visits Kashmir Centre Brussels Indonesia Willing to Invest in Gilgit-Baltistan Compiled & Edited Agriculture Sector by • Other Developments Dr Priyanka Singh Work on Diamer-Bhasha Dam to Begin this Year Mangla Dam Raising Project Opening Protested INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES No. 1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg February 2010 New Delhi-110 010 1 Jammu & Kashmir (Source: Based on the Survey of India Map, Govt of India 2000 ) A Monthly Newsletter on Pakistan Occupied Kashmir 2 About this Issue The suicide bomb attack in Muzaffarabad on January 6 has raised serious concerns amongst people in PoK which otherwise is a peaceful region. The spate of such attacks has been continuously hitting PoK ever since June 2009 attack in which an army base was targeted. Even though some groups have claimed responsibility of the attack, it is unclear as to who is behind these violent incidents. Militant training camps are operative in PoK for long; however bomb attacks in PoK is comparatively a new development.