The European External Action Service and National Diplomacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Black Book' on the Corporate Agenda of the Barroso II Commission

The record of a Captive Commission The ‘black book’ on the corporate agenda of the Barroso II Commission Corporate Europe Observatory Table of contents Introduction 3 1. Trade 5 2. Economic policy 7 3. Finance 9 4. Climate change 12 5. Agriculture 15 6. Water privatisation 18 7. The citizens initiative 20 8. Regulation 22 9. Lobbying ethics and transparency 23 Conclusion 27 Cover picture: Group photo of the ERT, from left to right, in the 1st row: Wim Philippa, Secretary General of the ERT, Leif Johansson, President of AB Volvo and CEO of Volvo Group and Chairman of the ERT, José Manuel Barroso, Gerard Kleisterlee, CEO and Chairman of the Board of Management of Royal Philips Electronics and Vice-Chairman of the ERT, and Paolo Scaroni, CEO of Eni, in the 2nd row: Aloïs Michielsen, Chairman of the Board of Directors of Solvay, César Alierta Izuel, Executive Chairman and CEO of Telefónica, Zsolt Hernádi, Chairman and CEO of MOL and Chairman of the Board of Directors of MOL, Paulo Azevedo, CEO of Sonae, and Bruno Lafont, CEO of Lafarge (Photo: EC Audiovisual Services/European Commission) Published by Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), May 2014 Written by Corporate Europe Observatory Editing: Katharine Ainger Design: Stijn Vanhandsaeme Contents of the report may be quoted or reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that the source of information is acknowledged 2 The record of a captive Commission Introduction With the upcoming European elections, the term of the Thus an increase in the competence of the Commission European Commission is coming to an end, and it has been tends to be directly proportional with corporate capture a term like few others. -

Horasis Global Meeting 6-9 April 201 9, Cascais, Portugal a Horasis Leadership Event

Horasis Global Meeting 6-9 April 201 9, Cascais, Portugal a Horasis leadership event Catalyzing the Benefits of Globalization Co-hosts: City of Cascais Government of Portugal inspirin g our future Upcoming Horasis events: Horasis India Meeting Segovia, Spain, 23-24 June 2019 Horasis China Meeting Las Vegas, USA, 28-29 October 2019 Horasis Asia Meeting Binh Duong New City, Vietnam, 24-25 November 2019 Horasis is a global visions community dedicated to inspiring our future. (www.horasis.org) Horasis Global Meeting 6-9 April 201 9, Cascais, Portugal a Horasis leadership event Catalyzing the Benefits of Globalization Co-hosts: City of Cascais Government of Portugal Co-chairs: Esko Aho, Chairman Cinia Oy; Former Prime Minister Finland José Manuel Barroso Vice-Chairman, Goldman Sachs International, United Kingdom Galia Benartzi Co-Founder, Bancor, Switzerland Uzoma Dozie Chief Executive Officer, Diamond Bank, Nigeria Brian A. Gallagher President and Chief Executive Officer, United Way Worldwide, USA Megan Jing Li Managing Director, Shanghai iMega Industry Co., China Eva-Lotta Sjöstedt Chief Executive Officer, Georg Jensen, Denmark Nandini Sukumar Chief Executive Officer, The World Federation of Exchanges, United Kingdom Ann Winblad Managing Partner, Hummer Winblad Venture Partners, USA Deborah Wince-Smith President, United States Council on Competitiveness, USA Vladimir Yakunin Chairman, Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute, Russia Knowledge Partners: CIP – Confederation of Portuguese Business Estoril Sol IE University Oxford Analytica Publicize Turismo de Portugal 1 Welcome I warmly welcome you to the 2019 Horasis Global Meeting and sincerely hope that you will enjoy the discussions. My thanks go to the City of Cascais and the Portuguese Government for co-hosting the event . -

Eu/S3/09/12/A European and External Relations

EU/S3/09/12/A EUROPEAN AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE AGENDA 12th Meeting, 2009 (Session 3) Tuesday 3 November 2009 The Committee will meet at 10.15 am in Committee Room 1. 1. Decision on taking business in private: The Committee will decide whether to take items 5 and 6 in private. 2. China Plan inquiry: The Committee will take evidence from— Iain Smith MSP, Convener of the Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee. 3. European Union matters of importance to Scotland: The Committee will take evidence from the following Scottish MEPs— Catherine Stihler MEP, and Ian Hudghton MEP, European Parliament. 4. Brussels Bulletin: The Committee will consider the Brussels Bulletin. 5. Impact of the financial crisis on EU support for economic development: The Committee will consider responses received to its report from the Scottish Government and the European Commission. 6. Treaty of Lisbon inquiry: The Committee will consider the approach to its inquiry. Lynn Tullis / Simon Watkins Clerks to the European and External Relations Committee Room TG.01 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5234 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] EU/S3/09/12/A The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda Item 2 Paper from the Clerk EU/S3/09/12/1 Agenda Item 3 Paper from the Clerk EU/S3/09/12/2 Agenda Item 4 Brussels Bulletin EU/S3/09/12/3 Agenda Item 5 Paper from the Clerk (Private Paper) EU/S3/09/12/4 (P) Agenda Item 6 Paper from the Clerk (Private Paper) EU/S3/09/12/5 (P) EU/S3/09/12/1 European and External Relations Committee 12th Meeting, 2009 (Session 3), Tuesday, 3 November 2009 China Plan inquiry Background 1. -

Download (18.394 Kb

IP/09/1867 Brussels, 2 December 2009 Copenhagen conference must produce global, ambitious and comprehensive agreement to avert dangerous climate change The European Commission today underlined the crucial importance of reaching a global, ambitious and comprehensive climate agreement at the UN climate change conference in Copenhagen on 7-18 December. The European Union will be working to achieve maximum progress towards finalisation of an ambitious and legally binding global climate treaty to succeed the Kyoto Protocol in 2013. The conference must settle the key political elements of the treaty and set up a process and mid-2010 deadline for completing the full text. The Copenhagen agreement must also incorporate a 'fast start' deal allowing for immediate implementation or preparation of certain actions, including financial assistance to least developed countries. Commission President José Manuel Barroso and Environment Commissioner Stavros Dimas will both participate in the conference, as will some 90 other world leaders. President Barroso said: "In Copenhagen world leaders must take the bold decisions needed to stop climate change from reaching the dangerous and potentially catastrophic levels projected by the scientific community. We must seize this chance to keep global warming below 2°C before it is too late. But Copenhagen is also an historic opportunity to draw the roadmap to a global low-carbon society, and in so doing unleash a wave of innovation that can revitalise our economies through the creation of new, sustainable growth sectors and "green collar" jobs. The European Union has set the pace with our unilateral commitment to cut emissions 20% by 2020 and our climate financing proposals for developing countries. -

A Radical Greek Evolution Within the Eurozone

A radical Greek evolution within the eurozone For John Milios, seen as the most hardline of Alexis Tsipras’s advisers, the country’s humanitarian crisis is the top priority John Milios’s phone rings a lot these days. There are hedge funds and financial institutions and investors, all curious to know what the German-trained professor thinks. As chief economist of Syriza, the far-left party that has sent markets into a tailspin as it edges ever closer to power in Greece, the academic has had a prominent role in devising the group’s financial manifesto. He is the first to concede the programme is radical. “I am a Marxist,” he says. “The majority [in Syriza] are.” Sipping green tea in his favourite Athens cafe, he explains: “Alternative approaches to the economy and society have been excluded by the dominant narrative of neoliberalism.” Milios, who attended Athens College, the country’s most prestigious private school – graduating in the same class as the former prime minister George Papandreou –is part of an eclectic group of experts advising Syriza’s leader, Alexis Tsipras, on the economy. Others include the Oxford-educated Euclid Tsakalotos, the political economist and shipping family heir Giorgos Stathakis, the leftwing veteran Giannis Dragasakis and the Texas-based academic Yanis Varoufakis. If the Athenian parliament fails to elect a new head of state by 29 December, the Greek constitution demands that snap polls are called. The ruling coalition’s narrow majority has made it unlikely that the government’s candidate, Stavros Dimas, will get the presidency. With the radicals in the ascent, Milios and his fellow Marxists are likely to take the reins of the EU’s weakest economy. -

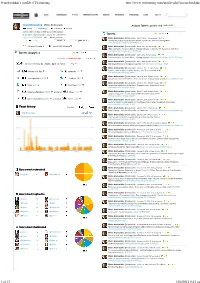

@Androulakis's Profile // Twitonomy

@androulakis's profile // Twitonomy http://www.twitonomy.com/profile.php?sn=androulakis @androulakis Mimis Androulakis Analyze Twitter's profile of @ androulakis 294 tweets 1,953 following 32,699 followers 542 listed Joined Twitter on May 3, 2008 as user #14,638,433 Συγγραφέας, δηµοσιογράφος, λάτρης του ραδιοφώνου. Tweets http://t.co/z0cT8Z5mUH Athens, Greece Mimis Androulakis @androulakis April 11, 2014, 7:14 am via web 0 3 Does not follow you Βουντού στις αγορές : Εµείς λέµε ούτε placebo, ούτε nocebo αλλά crisis management mimisandroulakis.blogspot.gr/2014/04/placeb… 17 followers/following 17 listed/1,000 followers Mimis Androulakis @androulakis April 9, 2014, 9:35 am via web 1 2 “Εδώ είναι Κρήτη , εδώ είναι ο Νότος ”, ξαδέλφη Άνγκελα ! - οι Μινωίτες στη Γερµανία το 1400 π.Χ.! mimisandroulakis.blogspot.gr/2014/04/blog-p… Tweets Analytics Mimis Androulakis @androulakis April 9, 2014, 7:31 am via web 3 2 “Εδώ είναι Κρήτη , εδώ είναι ο Νότος ”, ξαδέλφη Άνγκελα ! mimisandroulakis.blogspot.gr/2014/04/blog-p… Last updated 13 minutes ago Mimis Androulakis @androulakis April 7, 2014, 8:35 am via web 1 1 294 tweets from May 03, 2008 to April 14, 2014 1 Πάει καιρός που έκανες το κάρβουνο χρυσάφι mimisandroulakis.net/?page_id=448 Mimis Androulakis @androulakis March 31, 2014, 2:44 pm via web 2 4 tweets per day retweets 1% Άργησες πολύ , το ‘ χασες το τρένο , άργησες πολύ , δε σε περιµένω (M.A.) 0.14 2 mimisandroulakis.net/?page_id=448 Mimis Androulakis @androulakis March 26, 2014, 5:36 pm via web 1 3 103 user mentions 0.35 41 replies 14% Μια µυστική -

Archons Lead Religious Freedom Mission to the European Union In

securing religious freedom RIGHTS for the ecumenical patriarchate JAN • FEB • MAR 2010 www.archons.org Archon Leadership tribute dinner honors Archbishop Demetrios of America PAGE 16 Archons lead Religious Freedom Mission to the European Union in support of the Ecumenical Patriarchate With the blessings of His Eminence Archbishop Demetrios of America, Exarch of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, a delegation from the Order of St. Andrew, led by Archon reactions Ambassador George L. Argyros and National Commander Anthony J. Limberakis, MD, from the turkish press participated in a Religious Freedom Mission to the European Union in pursuit of human PAGE 10 rights and religious freedom for the Ecumenical Patriarchate from Jan 26–Feb 7. Continued on page 2 » His All Holiness honored by Prince Albert of Monaco for Environmental Leadership Turkish citizens hold demonstration outside PAGE 20 Phanar supporting religious minorities demonstration in support of minorities was organized A on Saturday, January 9, outside the compound of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul. The event was organized by a coalition of liberal and peacemaker organizations named ‘70 Million Steps Against Coups’. Continued on page 18 » Archon Legal Counselor Christopher Stratakis, His Eminence Metropolitan Emmanuel of France, Archon Ambassador George Argyros, National Commander Anthony J. Limberakis, MD, Archon Spirtual Advisor Fr. Alex Karloutsos, and Mr. Robert Lapsely, former assistant Secretary of State for California (top), prior to their meeting at the Council of the EU in Brussels. c. gallo The Order of Saint Andrew, Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarchate 1 RELigiOuS FREEDOM MiSSiON The Order’s fundamental goal and mission is to promote the religious freedom, wellbeing and advancement of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which is headquartered in Istanbul, Turkey. -

Conference on the Future of Europe

BRIEFING Conference on the Future of Europe SUMMARY After many debates and statements of principle in recent years, the time for a more structured discussion on the future of Europe's development has arrived. The Conference on the Future of Europe, announced by the Commission's President Ursula von der Leyen in her inaugural address, is set to start after a long period of standstill owing not only to changed priorities brought by the coronavirus pandemic, but also to lengthy negotiations among the institutions. The aim of the conference is to debate how the EU should develop in the future, identify where it is rising to the challenges of current times, and enhance those areas that need reform or strengthening. A key aspect of this initiative is to bring the public closer to the EU institutions, listen to people's concerns, involve them directly in the process of the Conference and provide an adequate and meaningful response. In this respect, the ambition is to set up pan-European forums for discussion, for the first time ever, where citizens of all Member States can debate the EU's priorities and make recommendations, to be taken into account by the political-institutional powers that be and, ideally, translated into practical measures. The pandemic hit as the preparation of the conference was just beginning and inevitably caused a delay. In March 2021, the European Parliament, the Council of the EU and the European Commission agreed on a joint declaration, laying down the common rules and principles governing the conference. It was agreed that the leadership of the conference would be shared by the three institutions, with the conference chaired jointly by their three presidents. -

Calendrier Du 25 Janvier Au 31 Janvier 2021

European Commission - Weekly activities Calendrier du 25 janvier au 31 janvier 2021 Brussels, 22 January 2021 Calendrier du 25 janvier au 31 janvier 2021 (Susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Déplacements et visites Lundi 25 janvier 2021 Mr Frans Timmermans participates via videoconference call in the Climate Adaptation Summit 2021. Mr Frans Timmermans participates in the event on ‘Making housing a human right for all: progressive ideas for the future', organised by the PES (European Social Party) Group in the Committee of the Regions. Mr Frans Timmermans receives Ms Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris. Ms Margrethe Vestager holds a videoconference call with Mr Michał Kurtyka, Minister for Climate and Environment of Poland. Ms Margrethe Vestager holds a videoconference call with Mr Thomas Bellut, Director General of ZDF, German Television. Ms Margrethe Vestager holds a videoconference with Mr Leo Varadkar, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment of Ireland. Ms Margrethe Vestager holds a videoconference call with Mr Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google. Mr Valdis Dombrovskis receives Mr Nikos Dendias, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Greece. Mr Valdis Dombrovskis receives Ms Arancha González Laya, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Spain. Mr Maroš Šefčovič receives Ms Arancha González Laya, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Spain. Ms Vĕra Jourová holds a videoconference call with Lithuanian judiciary representatives Ms Vĕra Jourová holds a videoconference call with Ms Inés Arrimadas, Leader of the Spanish Citizens Party (Ciudadanos). Mr Margaritis Schinas participates via videoconference in an interview with students from Den Haag University. Mr Margaritis Schinas participates via videoconference in the International Holocaust Remembrance Day 2021 event jointly hosted by the European Commission & the European Jewish Congress. -

THE JUNCKER COMMISSION: an Early Assessment

THE JUNCKER COMMISSION: An Early Assessment John Peterson University of Edinburgh Paper prepared for the 14th Biennial Conference of the EU Studies Association, Boston, 5-7th February 2015 DRAFT: Not for citation without permission Comments welcome [email protected] Abstract This paper offers an early evaluation of the European Commission under the Presidency of Jean-Claude Juncker, following his contested appointment as the so-called Spitzencandidat of the centre-right after the 2014 European Parliament (EP) election. It confronts questions including: What will effect will the manner of Juncker’s appointment have on the perceived legitimacy of the Commission? Will Juncker claim that the strength his mandate gives him license to run a highly Presidential, centralised Commission along the lines of his predecessor, José Manuel Barroso? Will Juncker continue to seek a modest and supportive role for the Commission (as Barroso did), or will his Commission embrace more ambitious new projects or seek to re-energise old ones? What effect will British opposition to Juncker’s appointment have on the United Kingdom’s efforts to renegotiate its status in the EU? The paper draws on a round of interviews with senior Commission officials conducted in early 2015 to try to identify patterns of both continuity and change in the Commission. Its central aim is to assess the meaning of answers to the questions posed above both for the Commission and EU as a whole in the remainder of the decade. What follows is the proverbial ‘thought piece’: an analysis that seeks to provoke debate and pose the right questions about its subject, as opposed to one that offers many answers. -

Ana Paula Zacarias Is a Career Diplomat of the Portuguese Foreign Service Since 1984

58 Ana Paula Zacarias is a career diplomat of the Portuguese Foreign Service since 1984. She started her career in Lisbon as Secretary of Embassy at the Protocol Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs then as a Counsellor for International Relations at the Office of the President of the Republic. In July 1988, Mrs Zacarias joined the Embassy of Portugal to the USA in Washington as First Secretary. Then moved to Brazil to become Consul of Portugal to Paraná and Santa Catarina. In 1996, Mrs Zacarias went back to her home land for four years to first take over the post of Director of Press and Information Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs then, two years later in 1998 and still in Lisbon, she became Vice-President of A European–South American Dialogue A European–South the Camões Institute (the Institute for External Cultural Relations). In Paris, France, as of November 2000, Mrs Zacarias became Deputy Permanent Representative of Portugal to Unesco and Permanent Representative to União Latina. Five years later in 2005, she was posted in Talinn becoming the First Resident Ambassador of Portugal to Estonia. In 2009, she was International Security designated Deputy Permanent Representative of Portugal to the European Union, serving her country in Brussels for the next two years. After joining the European Union External Action Service, Mrs Zacarias was nominated Head of the EU Delegation to Brazil arriving in Brasilia in May 2011. X Conference of Forte de Copacabana of Forte X Conference 59 Brazil Emerging in the Global Security Order European Common Security and Defence Policy Ana Paula Zacarias The idea of a common Security Strategy for Europe has evolved incre- mentally since the early days of the European Community. -

'Greece's New Anti-Austerity Coalition'

Greece’s new anti-austerity coalition Standard Note: SN07076 Last updated: 28 January 2015 Author: Rob Page and Lorna Booth Section International Affairs and Defence Section/Economic Policy and Statistics Section The recent parliamentary election in Greece was a triumph for the radical left-wing Syriza party, which became the largest party and fell two seats short of an overall majority. It has formed a coalition administration with the small Independent Greeks party, with Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras as Prime Minister. The outgoing government had imposed strict austerity measures in return for bailout loans from the “troika” (European Union, International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank). Syriza, by contrast, is often portrayed as anti- austerity and anti-bailout. Some have speculated that the policies of the new Syriza-led administration might ultimately lead to a Greek exit from the Eurozone. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is required. This information is provided subject to our general terms and conditions which are available online or may be provided on request in hard copy. Authors are available to discuss the content of this briefing with Members and their staff, but not with the general public.