And the Mountains Echoed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perpetual Analysis and Relevance of Love Bond in the Novels of Khaled Hosseini Dr

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences, 5(2) Mar-Apr 2020 |Available online: https://ijels.com/ Perpetual Analysis and Relevance of Love Bond in the Novels of Khaled Hosseini Dr. Madhvi Rathore1, Vandana Chundawat2 1Associate Professor, Department of English, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Bhupal Nobles’ University, Udaipur, India 2Research Scholar, Department of English, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Bhupal Nobles’ University, Udaipur, India Abstract— Khaled Hosseini is one of the most prolific Afghan-American Writer who beautifully investigates into the delicacies of human relationships. In his novels, Hosseini has stated his concern about the despicable conditions of the people in general and women in specific who have been doubly disregarded –one by the society and the other inside the four walls of their homes. Against the backdrop of such a ruptured environment, the strong factor that gives strength to the characters is the bond of love and trustworthiness as reflected in The Kite Runner, A Thousand Splendid Suns and the Mountains Echoed. Hosseini makes it vibrant and clear that these love stories are very much unlike the platonic narratives of romantic love hood between a man and a woman. They are not traditional, they are the stories of love where “characters are saved by love and humanism”. (2003 interview). Their love is tried and testified in extreme difficult situations and the characters are left to realize their individual paths by reuniting to their loved ones at their own risk. It is eventually this yearning for love that draws characters out of their loneliness, gives them power and strength to transcend their boundaries, to tussle with their weaknesses and perform shocking acts of self-sacrifice. -

Quest for Identity and Redemption in Khaled Hosseini's the Kite Runner

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(P): 2347-4564; ISSN(E): 2321-8878 Vol. 5, Issue 5, May 2017, 37-40 © Impact Journals QUEST FOR IDENTITY AND REDEMPTION IN KHALED HOSSEINI'S THE KITE RUNNER RAKHPREET KAUR WALIA RIMT University, Punjab, India ABSTRACT “ For you, a thousand times over! “ The Afghan born American novelist and Physician, Khaled Hosseini is worldwide acknowledged as the true gifted teller of tales of his native land, Afghanistan. Hosseini grew up there in a middle-class family, and is the eldest of five siblings. His father was a civil diplomat and his mother was a teacher of Farsi and History at a large high school. As a result, Khaled was very fond of Persian Poetry and was deeply influenced by her mother's books. He was also fond of reading novels and short-stories. In 1976, when Khaled was 11, his father was transferred to a diplomatic post in Paris. So the whole family moved to France. Residing in Paris was a period of discovery of many new things for him. The year 1978 was a period of tremendous calamity in the history of Afghanistan, as the communist forces took control in a coup in the country. Khaled and his family could witness all upheavals going on in his land through television. At last, they had an idea of not returning back to Afghanistan. So, they decided to migrate to the United States. First, they sought political asylum in the States and then got settled in California. It was financially very difficult for them to survive there. -

Sea Prayer Khaled Hoesseini

SEPTEMBER 2018 Sea Prayer Khaled Hoesseini A heart-wrenching story from the international bestselling author of The Kite Runner Sales points • Khaled Hosseini is one of the most widely read and beloved novelists in the world. His books have sold over 8 million copies in UK markets alone, and over 55 million copies in more than 70 countries worldwide • Impelled to write this story by the haunting image of young Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy whose body washed upon the beach in Turkey in September 2015, Hosseini hopes to pay tribute to the millions of families, like Kurdi 's, who have been splintered and forced from home by war and persecution Description A heart-wrenching story from the international bestselling author of The Kite Runner On a moonlit beach a father cradles his sleeping son as they wait for dawn to break and a boat to arrive. He speaks to his boy of the long summers of his childhood, recalling his grandfather 's house in Syria, the stirring of olive trees in the breeze, the bleating of his grandmother 's goat, the clanking of her cooking pots. And he remembers, too, the bustling city of Homs with its crowded lanes, its mosque and grand souk, in the days before the sky spat bombs and they had to flee. When the sun rises they and those around them will gather their possessions and embark on a perilous sea journey in search of a new home. About the Author Khaled Hosseini is one of the most widely read and beloved novelists in the world, with over 55 million copies of his books sold in more than 70 countries. -

First-Year Experience

books for FIRST-YEAR EXPERIENCE & COMMON READING PROGRAMS FYE2016 / 2017 Dear FYE Participants, CONTENTS We are delighted to present the eighth edition of Penguin’s FYE Favorites 3 First-Year Experience catalog and excited to continue the Contemporary Fiction 13 connection between our great books and authors and your Literary Classics 23 campus-wide and common reading programs. Penguin General Nonfiction 24 Publishing Group, the largest trade book publisher in col- Memoir & Biography 28 lege markets, possesses the world’s most prestigious list of History 34 contemporary authors and a backlist of unparalleled breadth, Motivation & Creativity 37 depth, and quality. Philosophy & Religion 42 I’m happy to assist you in any way possible with choice Current Events 43 of titles, free examination copies, questions about author Science & Technology 45 availability, and pricing discounts (see page 55). You’re Environment 49 also welcome to contact your Penguin college rep directly. Index 52 Unique to trade publishing, our college reps have assisted Testimonials 53 countless schools across the country in picking the perfect Speakers Bureau 54 book for their FYE programs. We are also happy to connect FYE Ordering Info 55 you to our Penguin Random House Speakers Bureau, with whom we work very closely. For more details see page 54. Introducing our college reps We have thousands of other titles available that we are un- able to list here, and our team is ready to work with you to STEPHANIE SMITH fnd that perfect book for your campus. To get the ball rolling East Coast College and to request free exam copies (please include both title and Field Sales Representative [email protected] ISBN), email me at [email protected]. -

Afghan Theatres Since 9/11: from and Beyond Kabul

Afghan theatres since 9/11: from and beyond Kabul A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2016 Chin Min Edmund Chow School of Arts, Languages and Cultures List of Contents List of Figures and Images 3 List of Plays/ Performances Analysed 5 Abbreviations 6 Foreign Expressions 8 Abstract 9 Declaration and Copyright Statement 10 Acknowledgements 11 The Author 12 Chapter 1 Afghanistan: 13 Lights, Camera, Death Threats Chapter 2 Historical Brief: 70 Tropes about Afghanistan Chapter 3 ‘From Kabul’: 112 Locating Afghan Cultures Chapter 4 ‘From and Beyond Kabul’: 166 Saving Afghanistan Chapter 5 ‘Beyond Kabul’: 219 Imaginary Texture of the Real Chapter 6 Circulation of Afghanistan 274 References 289 Appendix 1 Cultural Timeline: 324 Afghan Theatres and other Cultural Activities in view of Wider Politics Appendix 2 Images 335 Final word count: 80, 217 2 List of figures and images Figure 1 The ‘circuit of culture’ model 29 Figure 2 Administrative Divisions in Afghanistan 2009 335 Figure 3 Afghanistan and the Durand Line 336 Plate 1 Afghan audiences at Kabul Nanderi, c. 1974 337 Plate 2 Afghan women’s dressing, c. 1974 337 Plate 3 Performance with actress on stage at Kabul 338 Nanderi, c. 1974 Plate 4 Farida Raonaq in a play by Molière 338 Plate 5 Costume design in Molière’s plays 339 Plate 6 Parwaz Puppet Theatre performance 339 Plate 7 Parwaz Puppet Theatre performance in rural 340 province Plate 8 Storyteller at the beginning of Kaikavus 340 Plate 9 Sohrab defeats -

The Prayer of Refugee Children

Advances in Literary Study, 2021, 9, 73-83 https://www.scirp.org/journal/als ISSN Online: 2327-4050 ISSN Print: 2327-4034 The Prayer of Refugee Children Naiting He Qinghai Normal University, Xining, China How to cite this paper: He, N. T. (2021). Abstract The Prayer of Refugee Children. Advances in Literary Study, 9, 73-83. As a member of human society, children are the future of the family, country, https://doi.org/10.4236/als.2021.92009 nation, and mankind indeed. With the development of human civilization, the protection of children’s rights attracts more and more attention due to Received: March 5, 2021 Accepted: April 18, 2021 increasing refugee crisis. Especially the group of refugee children caused by Published: April 21, 2021 armed conflicts has aroused focus and sympathy worldwide. As an Afg- han-born American novelist, Khaled Hosseini’s literary works are all about Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and the theme of refugees. In particular, his new work Sea Prayer which was pub- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative lished in 2018 shows the issue of refugee children in a bald statement. With a Commons Attribution International strong desire to expect people to look at this issue from a humanitarian pers- License (CC BY 4.0). pective, Khaled Hosseini’s stresses the importance of mutual understanding http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ and peaceful coexistence, which happens to coincide with the idea of a com- Open Access munity with shared future for mankind. This paper puts forward the issue of refugee children from the perspective of the community with a shared future for mankind by analyzing Khaled Hosseini and his new work Sea Prayer. -

Imagining Afghanistan: Global Fiction and Film of the 9/11 Wars

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-16-2019 Imagining Afghanistan: Global Fiction and Film of the 9/11 Wars Alla Ivanchikova Hobart and William Smith Colleges Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ivanchikova, Alla, Imagining Afghanistan: Global Fiction and Film of the 9/11 Wars. (2019). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Comparative Cultural Studies Ari Ofengenden, Series Editor The series examines how cultural practices, especially contemporary creative media, both shape and themselves are shaped by current global developments such as the digitization of culture, virtual reality, global interconnectedness, increased people flows, transhumanism, environ- mental degradation, and new forms of subjectivities. We aim to publish manuscripts that cross disciplines and national borders in order to provide deep insights into these issues. Alla Ivanchikova Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2019 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-846-8 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-55753-975-5. -

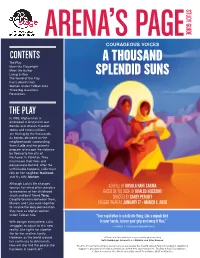

A Thousand Splendid Suns Reality

ARENA’S PAGE STUDY GUIDE COURAGEOUS VOICES CONTENTS A THOUSAND The Play Meet the Playwright Meet the Author Living in War SPLENDID SUNS The World of the Play Facts About Islam Women Under Taliban Rule Three Big Questions Resources THE PLAY In 1992, Afghanistan is embroiled in brutal civil war. Bombs and attacks threaten towns and cities; civilians are fleeing by the thousands. As bombs descend on the neighborhoods surrounding them, Laila and her parents prepare to escape the violence by fleeing to the city of Peshawar in Pakistan. They must leave their lives and possessions behind. After the unthinkable happens, Laila must rely on her neighbor, Rasheed, and his wife, Mariam. Although Laila’s life changes forever, her mind often wanders ADAPTED BY URSULA RANI SARMA to memories of her childhood BASED ON THE BOOK BY KHALED HOSSEINI crush and best friend Tariq. Despite tensions between them, DIRECTED BY CAREY PERLOFF Mariam and Laila work together KREEGER THEATER | JANUARY 17 - MARCH 1, 2020 to survive the daily persecution they face as Afghan women under Taliban rule. “Your reputation is a delicate thing. Like a mynah bird With danger everywhere, Laila in your hands, loosen your grip and away it flies.” struggles to adjust to this new — Fariba, A Thousand Splendid Suns reality. She fights for a better life for her and her family. However, as the world around A Thousand Splendid Suns is generously sponsored by her continues to deteriorate, Beth Newburger Schwartz and Michele and Allan Berman. how will she find the peace she The D.C. Ticket Partnership is generously sponsored by the Paul M. -

Khaled Hosseini, and the Mountains Echoed (Bloomsbury, 2013) Khaled

Khaled Hosseini, And the Mountains Echoed (Bloomsbury, 2013) Khaled Hosseini’s And the Mountains Echoed sees the author of The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns return to his native Afghanistan once more with a story of sacrifice and its consequences. It begins in 1952 as young siblings Abdullah and Pari are led by their father Saboor across the desert, towards a meeting which will tear them apart: Pari is to be sold to a rich couple to allow the rest of the family to survive the winter, the finger cut to save the hand. We follow the consequences of this decision for those involved, and how this then affects others near them, in a series of nine narratives from different perspectives. The narration moves from the siblings’ step-mother Parwana in 1949 to Adbullah’s daughter in 2010, from a poor village in Afghanistan to the suburbs of the United States, but each story is linked to the others and the siblings in some way. It truly is a novel of echoes. The narrative styles used for these different sections vary widely. We are first given an almost campfire-like experience with Saboor reciting a fairytale to his two children, Abdullah and Pari; this is a first-person present tense story framed by third- person past tense narration. We then move into Abdullah’s mind the following day as he walks with his father and sister toward Kabul, in a simple third-person past tense section. Parwana, Saboor’s wife and Abdullah and Pari’s stepmother, then tells the story of how she came to be with her husband in third-person present tense with flashbacks to the past. -

Thematic Journal of Applied Sciences (Volume-1 Issue-1)

Thematic Journal of Applied Sciences (Volume-1 Issue-1) 1 Thematic Journal of Applied Sciences (Volume-1 Issue-1) Thematic Journal of Applied Sciences Volume 1, Issue 1, March 2021 Internet address: http://ejournals.id/index.php/TJAS/issue/archive E-mail: [email protected] Published by Thematics Journals PVT LTD Issued Bimonthly Chief editor S. G. Ahmed Professor of Computational Mathematics and Numerical Analysis Faculty of Engineering, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt, P. O. Box 44519 Requirements for the authors. The manuscript authors must provide reliable results of the work done, as well as an objective judgment on the significance of the study. The data underlying the work should be presented accurately, without errors. The work should contain enough details and bibliographic references for possible reproduction. False or knowingly erroneous statements are perceived as unethical behavior and unacceptable. Authors should make sure that the original work is submitted and, if other authors' works or claims are used, provide appropriate bibliographic references or citations. Plagiarism can exist in many forms - from representing someone else’s work as copyright to copying or paraphrasing significant parts of another’s work without attribution, as well as claiming one’s rights to the results of another’s research. Plagiarism in all forms constitutes unethical acts and is unacceptable. Responsibility for plagiarism is entirely on the shoulders of the authors. Significant errors in published works. If the author detects significant errors or inaccuracies in the publication, the author must inform the editor of the journal or the publisher about this and interact with them in order to remove the publication as soon as possible or correct errors. -

4.Pratibha-Article.Pdf

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) “There is only one, only one skill a woman like you and me needs in life…. And it’s this: tahamul. Endure”: A Feminist Analysis of the Female Characters in Khaled Hosseini’s And the Mountains Echoed and A Thousand Splendid Suns Prathibha P. Research Scholar, Department of English Farook College, Affiliated to University of Calicut Calicut, Kerala Abstract Women‟s liberation and empowerment has more often than not been battled for in books by female writers. Khaled Hosseini, the young Afghan-American writer whose remarkable contribution to fiction makes him prominent around the globe proves that male authors too can produce feminist fiction with élan. In his novels A Thousand Splendid Suns and And the Mountains Echoed, he depicts unique female characters such as Nana, Mariam, Laila, Nila Wahdati, Amra and Pari who are oppressed by the rigid patriarchal Afghan society. The author embarks on a new perspective. He does not merely display the marginalization of women and their victimization but also counteracts it by bringing forward female characters who either voice feminism or are epitomes of endurance and resistance. Through his mindboggling heroines, he deplores the social and cultural structures that support the degradation and devaluation endured by women. This paper attempts a feministic analysis of the mental strength and will power of the women characters who rise from their miserable plight like „splendid suns‟. Keywords: Resistance, oppression, endurance, marginalization, violence, conflicts, feminism. In his works, Khalid Hosseini explores the representation of females who are subject to double standards, mistreatment, corruption, and savagery which is authorized by patriarchal benchmarks and political structures .Feminism starts with a consciousness that women are excluded from “male cultural, social, sexual, political and intellectual discourse. -

Afganistan from Within and Outside in Khaled Hosseini's Novel and the Mountains Echoed Revista Publicando, 5 No 16

Afganistan from Within and Outside in Khaled Hosseini's Novel And the Mountains Echoed Revista Publicando, 5 No 16. (1). 2018, 623-630. ISSN 1390-9304 Afganistan from Within and Outside in Khaled Hosseini's Novel And the Mountains Echoed Inara S. Alibayova1, Olga B. Karasik1 1 Kazan Federal University, [email protected] Abstract The article is devoted to the latest novel written by the American author of the Afghan origin Khaled Hosseini. It is well known that serious political and social changes occurred in Afghanistan in the twentieth century. Since the beginning of the Taliban’s rule, Afghanistan has been ranked not only as the country with an unstable political system but also began to associate as the center of terror and wars connected with nationalism and religious disagreements. All the cultural heritage of the country was left in the past. Khaled Hosseini tries to destroy the stereotypes about the country formed in the modern Western world. His novel And the Mountains Echoed came out six years after the publication of Thousand Splendid Suns and is very different this and previous ones. The action takes place not only in Afghanistan but also in USA, France, and Greece. The heroes are not only Afghans but also the representatives of other nationalities, whose fate is connected with Afghanistan. The previous Hosseini's works had such success, that the third novel came out in eight countries simultaneously in the corresponding translations. The ideas of And the Mountains Echoed are universal, based on human life, regardless of where the person was born, and to what nation, race and religion he belongs.