Australian Judicial Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex Parte Young After Seminole Tribe

RESPONSE EX PARTE YOUNG AFIER SEMINOLE TRIBE DAVID P. CuRm* My message is one of calm placidity: Not to worry; Ex parte Young1 is alive and well and living in the Supreme Court. By way of background let me say that I am that rara avis, a law professor who thinks Hans v. Louisiana2 was rightly decided.3 For the reasons given by Justice Bradley,4 I am quite convinced that the Fed- eral Question Clause of Article III does not extend the judicial power to suits against nonconsenting states. That being so, it follows that the much lamented first half of the decision in Seminole Tribe v. Floridas is also right, for a long series of decisions makes abundantly clear that Congress cannot give the federal courts jurisdiction over matters outside Article 1l.6 Nor do I consider Ex parte Young, as Justice Souter does in his dissenting opinion in Seminole Tribe, as an obvious corollary of Hans.7 On the contrary, Ex parte Young squarely contradicts that de- cision. For even if sovereign immunity was only a matter of form in * Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law, University of Chicago. B.A., University of Chicago; LL.B., Harvard. This Comment is based upon remarks made during a panel discussion at the annual meeting of the Association of American Law Schools in January 1997. 1 209 U.S. 123 (1908). 2 134 U.S. 1 (1890) (holding that judicial power of United States does not extend to suits against state by one of its own citizens unless state consents to be sued). -

Justice Richard O'connor and Federation Richard Edward O

1 By Patrick O’Sullivan Justice Richard O’Connor and Federation Richard Edward O’Connor was born 4 August 1854 in Glebe, New South Wales, to Richard O’Connor and Mary-Anne O’Connor, née Harnett (Rutledge 1988). The third son in the family (Rutledge 1988) to a highly accomplished father, Australian-born in a young country of – particularly Irish – immigrants, a country struggling to forge itself an identity, he felt driven to achieve. Contemporaries noted his personable nature and disarming geniality (Rutledge 1988) like his lifelong friend Edmund Barton and, again like Barton, O’Connor was to go on to be a key player in the Federation of the Australian colonies, particularly the drafting of the Constitution and the establishment of the High Court of Australia. Richard O’Connor Snr, his father, was a devout Roman Catholic who contributed greatly to the growth of Church and public facilities in Australia, principally in the Sydney area (Jeckeln 1974). Educated, cultured, and trained in multiple instruments (Jeckeln 1974), O’Connor placed great emphasis on learning in a young man’s life and this is reflected in the years his son spent attaining a rounded and varied education; under Catholic instruction at St Mary’s College, Lyndhurst for six years, before completing his higher education at the non- denominational Sydney Grammar School in 1867 where young Richard O’Connor met and befriended Edmund Barton (Rutledge 1988). He went on to study at the University of Sydney, attaining a Bachelor of Arts in 1871 and Master of Arts in 1873, residing at St John’s College (of which his father was a founding fellow) during this period. -

15. Judicial Review

15. Judicial Review Contents Summary 413 A common law principle 414 Judicial review in Australia 416 Protections from statutory encroachment 417 Australian Constitution 417 Principle of legality 420 International law 422 Bills of rights 422 Justifications for limits on judicial review 422 Laws that restrict access to the courts 423 Migration Act 1958 (Cth) 423 General corporate regulation 426 Taxation 427 Other issues 427 Conclusion 428 Summary 15.1 Access to the courts to challenge administrative action is an important common law right. Judicial review of administrative action is about setting the boundaries of government power.1 It is about ensuring government officials obey the law and act within their prescribed powers.2 15.2 This chapter discusses access to the courts to challenge administrative action or decision making.3 It is about judicial review, rather than merits review by administrators or tribunals. It does not focus on judicial review of primary legislation 1 ‘The position and constitution of the judicature could not be considered accidental to the institution of federalism: for upon the judicature rested the ultimate responsibility for the maintenance and enforcement of the boundaries within which government power might be exercised and upon that the whole system was constructed’: R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254, 276 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Fullagar and Kitto JJ). 2 ‘The reservation to this Court by the Constitution of the jurisdiction in all matters in which the named constitutional writs or an injunction are sought against an officer of the Commonwealth is a means of assuring to all people affected that officers of the Commonwealth obey the law and neither exceed nor neglect any jurisdiction which the law confers on them’: Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 211 CLR 476, [104] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). -

The Section 92 Revolution

Encounters with Constitutional Interpretation and Legal Education (2018) James Stellios (ed) Chapter 1 The Section 92 Revolution The Hon Stephen Gageler Nothing could be more disappointing to a legal scholar than to labour over the produc- tion of a treatise on an area of law only to see that treatise almost immediately rendered redundant by a revolutionary decision of an ultimate court. Equally and oppositely, nothing could be more satisfying to a young, ambitious and energetic legal scholar than to take part in the litigation which produces a revolutionary decision of an ultimate court on a topic squarely within his or her field of expertise. Michael Coper experienced the disappointment and the satisfaction. As a junior academic at the University of New South Wales, he turned his doctoral thesis entitled The Judicial Interpretation of Section 92 of the Australian Constitution into a 400-page book, which he published in 1983 as Freedom of Interstate Trade under the Australian Constitution. Just four years later, he accepted a brief to appear with Ron Sackville as junior counsel to the Solicitor-General for New South Wales, Keith Mason QC, on behalf of the Attorney-General for New South Wales intervening in the hearing before the High Court of Cole v Whitfield.1 When Cole v Whitfield was decided in 1988, his academic thesis was largely vindicated, the complexities of the case law which he had sought to tease apart and critique were largely swept away. As the result of the publication of that single judgment, his detailed, insightful and colourfully written book was destined immediately to be remaindered. -

A Case for Structured Proportionality Under the Second Limb of the Lange Test

THE BALANCING ACT: A CASE FOR STRUCTURED PROPORTIONALITY UNDER THE SECOND LIMB OF THE LANGE TEST * BONINA CHALLENOR This article examines the inconsistent application of a proportionality principle under the implied freedom of political communication. It argues that the High Court should adopt Aharon Barak’s statement of structured proportionality, which is made up of four distinct components: (1) proper purpose; (2) rational connection; (3) necessity; and (4) strict proportionality. The author argues that the adoption of these four components would help clarify the law and promote transparency and flexibility in the application of a proportionality principle. INTRODUCTION Proportionality is a term now synonymous with human rights. 1 The proportionality principle is well regarded as the most prominent feature of the constitutional conversation internationally.2 However, in Australia, the use of proportionality in the context of the implied freedom of political communication has been plagued by confusion and controversy. Consequently, the implied freedom of political communication has been identified as ‘a noble and idealistic enterprise which has failed, is failing, and will go on failing.’3 The implied freedom of political communication limits legislative power and the common law in Australia. In Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 4 the High Court unanimously confirmed that the implied freedom5 is sourced in the various sections of the Constitution which provide * Final year B.Com/LL.B (Hons) student at the University of Western Australia. With thanks to Murray Wesson and my family. 1 Grant Huscroft, Bradley W Miller and Grégoire Webber, Proportionality and the Rule of Law (Cambridge University Press, 2014) 1. -

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

The Commission's Submission

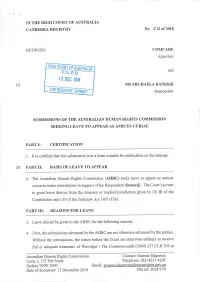

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CANBERRA REGISTRY No. C12 of 2018 BETWEEN: COMCARE Appellant HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA and FILED 12 DEC 2018 10 MS MICHAELA BANERTI THE REGISTRY SYDNEY Respondent SUBMISSIONS OF THE AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION SEEKING LEAVE TO APPEAR AS AMICUS CURIAE PART I: CERTIFICATION 1. It is certified that this submission is in a form suitable for publication on the internet. 20 PART II: BASIS OF LEAVE TO APPEAR 2. The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) seeks leave to appear as amicus curiae to make submissions in support of the Respondent (Banerji). The Court's power to grant leave derives from the inherent or implied jurisdiction given by Ch III of the Constitution and s 30 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART III: REASONS FOR LEAVE 3. Leave should be given to the AHRC for the following reasons. 4. First, the submissions advanced by the AHRC are not otherwise advanced by the parties. Without the submissions, the issues before the Court are otherwise unlikely to receive full or adequate treatment: cf Wurridjal v The Commonwealth (2009) 237 CLR 309 at Australian Human Rights Commission Contact: Graeme Edgerton Level 3, 175 Pitt Street Telephone: (02) 8231 4205 Sydney NSW 2000 Email: [email protected] Date of document: 12 December 2018 File ref: 2018/179 -2- 312-3. The Commission’s submissions aim to assist the Court in a way that it may not otherwise be assisted: Levy v State of Victoria (1997) 189 CLR 579 at 604 (Brennan CJ). 5. Secondly, the proposed submissions are brief and limited in scope. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Process, but Also Assumes a Role in the Administration of the Court

Mason process, but also assumes a role in the administration of the Court. Frank Jones Mason, Anthony Frank (b 21 April 1925; Justice 1972–87; Chief Justice 1987–95) was a member of the High Court for 23 years and is regarded by many as one of Australia’s great- est judges, as important and influential as Dixon.The ninth Chief Justice,he presided over a period ofsignificant change in the Australian legal system, his eight years as Chief Justice having been described as among the most exciting and important in the Court’s history. Mason grew up in Sydney, where he attended Sydney Grammar School. His father was a surveyor who urged him to follow in his footsteps; however, Mason preferred to follow in the footsteps of his uncle, a prominent Sydney KC. After serving with the RAAF as a flying officer from 1944 to 1945, he enrolled at the University of Sydney, graduating with first-class honours in both law and arts. Mason was then articled with Clayton Utz & Co in Sydney, where he met his wife Patricia, with whom he has two sons. He also served as an associate to Justice David Roper of the Supreme Court of NSW. He moved to the Sydney Bar in 1951, where he was an unqualified success, becoming one of Barwick’s favourite junior counsel. Mason’s practice was primarily in equity and commercial law,but he also took on a number ofconstitutional and appellate cases. After only three years at the Bar, he appeared before the High Court in R v Davison (1954), in which he successfully persuaded the Bench that certain sections of the Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth) invalidly purported to confer Anthony Mason, Justice 1972–87, Chief Justice 1987–95 in judicial power upon a registrar of the Bankruptcy Court. -

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: a Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon*

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: A Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon* The essential and distinctive feature of “a truly federal government” is the preservation of the separate existence and corporate life of each of the component States concurrently with that of the national government. Accepting that a number of polities are contemplated as coexisting within a federation does not, however, address the fundamental question of how legislative and executive powers are to be allocated among the constituent constitutional units inter se, nor the extent to which the various polities are immune from interference occasioned by their constitutional counterparts. These “federal” questions are fundamental as they ultimately define the prism through which one views the Constitution. Shifts in the lens have resulted in significant ramifications for intergovernmental relations. This article traces the development of the Melbourne Corporation doctrine in Australia, and undertakes a comparative analysis with the development of the cognate jurisprudence in the United States. Analysis is undertaken of the major Australian industrial relations decisions, such as the Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd, Re Australian Education Union; Ex parte Victoria, Queensland Electricity Commission v Commonwealth, and United Firefighters Union of Australia v Country Fire Authority, in this context. But one of the first and most leading principles on which the commonwealth and the laws are consecrated, is left the temporary possessors -

The New South Wales Legal Profession in 1917

Battles Overseas and At Home: The New South Wales Legal Profession in 1917. The Symposium 24 March 2012 Tony Cunneen [email protected] Comments welcome Synopsis: This paper focuses on the events of 1917 and is a part of a series on Lawyers in the First World War. Other papers in the series cover lawyers on Gallipoli and in 1916 as well as related topics may be accessed on the website of the Francis Forbes Society for Australian Legal History on http://www.forbessociety.org.au/ or by contacting the author directly at the above email address. Introduction: The activities of lawyers in the first decades of the twentieth century in general and the First World War in particular have received scant attention. The need to examine this area lies in lawyers’ importance in defining the early forms of Australian life after Federation and their leadership of many war related activities. The period of 1914-1918 was a time when the country was determining just how it would operate as an independent Federation yet also a full member of the British Empire – which was increasingly being seen as an international community of nations. An investigation of lawyers’ activities during the war challenges any stereotypes of a remote, isolated profession 2 and reveals a vibrant, human community steeped in shared values of service and cooperation and determined to play an active part in shaping the nation. war service, whether on the battlefield or the Home Front was seen as an essential part of that process. The development of the protectorate of Papua was part of that process. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000.