NYC TOHP Transcript 053 Yana Calou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

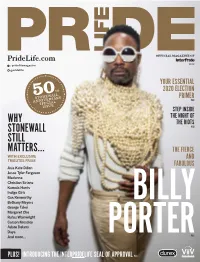

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

Utah Pride Festival's Prohibition on Firearms

EDWIN P. RUTAN, II RALPH BECKER CITY ATTORNEY MAYOR May 18, 2009 David Nelson Jeffrey L. Johnson Re: Utah Pride Festival’s Prohibition on Firearms Gentlemen: Your various e-mail messages to the Mayor and City Council have been referred to me for legal analysis. I respect your belief in the importance of your rights to carry your firearms as you understand those rights. However, I believe that your understanding of your rights under the law is incorrect in this specific instance. Based on Mr. Nelson’s April 14, 2009 e-mail, I understand your concern to be that the Gay Lesbian Bisexual Transgender Community Center of Utah doing business as Utah Pride Center has stated on the website for its Utah Pride Festival (the “Festival”) under “Festival Guidelines/Prohibited Items” that “No firearms … are permitted.” The “Festival Guidelines” also state that “The Utah Pride Festival is a private event. Please be advised that the event organizer, the Utah Pride Center reserves the right to decline admittance to anyone who violates the reasonable polices established by the Utah Pride Center.” You both note that the Utah Pride Center will be entering into a lease with Salt Lake City for portions of Washington Square and Library Square. You both assert that Salt Lake City is violating UCA Sections 53-5a-102 and 76-10-500 because it has not required the Utah Pride Center as lessee of property owned by the City to allow firearms to be carried at the Festival. I think that you are incorrectly interpreting both statutes. Section 53-5a-102(5) provides that: Unless specifically authorized by the Legislature by statute, a local authority or state entity may not enact, establish or enforce any ordinance, regulation, rule, or policy pertaining to firearms that in any way inhibits or restricts the possession or use of firearms on either public or private property.” (emphasis added) 451 SOUTH STATE STREET, ROOM 505, P.O. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 1982 – 2012 2012 Annual Report

International Association of Pride Organizers 30th ANNIVERSARY 1982 – 2012 2012 Annual Report InterPride Inc. – International Association of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Pride Organizers Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for organizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in the USA and is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organiza- tion under US law. It is funded by membership dues, sponsor- ship, merchandise sales and donations from individuals and organizations. Our Mission InterPride’s mission is to promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans- gender and Intersex (LGBTI) Pride on an international level and to encourage diverse com munities to hold and attend Pride Events. InterPride increases networking, communication and education among Pride Organizations. InterPride works together with other LGBTI and Human Rights organizations. InterPride’s relationship with its member organizations is one of advice, guidance and assistance when requested. We do not have any control over, or take responsibility for, the way our member organizations conduct their events. Regional Director reports contained within this Annual Report are the words, personal accounts and opinions of the authors involved and do not necessarily reflect the views of InterPride as an organization. InterPride accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of material contained within. InterPride can be contacted via email [email protected] or via our website. www.interpride.org © 2012 InterPride Inc. Information given in this Annual Report is known to be correct at the time of production September 20th, 2012 2 © InterPride Inc. | www.interpride.org 2012 Annual Report Table of Contents Corporate Governance 4 Executive Committee 4 Regional Directors 4 Regions and Member Organizations 6 InterPride Regions 6 Member Organizations 7 InterPride Inc. -

Major LGBT Global Events Updated November 5, 2012

Atlanta, Ga., U.S.A. Bisbee, Ariz., U.S.A. Brooklyn, N.Y., U.S.A. Chicago, Ill., U.S.A. Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.A. Dayton, Ohio, U.S.A. Erie, Pa., U.S.A. Florianopolis, Brazil Guadalajara, Mexico Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A. Kansas City, Mo., U.S.A. Lansing, Mich., U.S.A. Long Island, N.Y., U.S.A. Mexico City, Mexico Monterey, Calif., U.S.A. New Hope, Pa., U.S.A. AMERICAS Joining Hearts Atlanta Bisbee Pride Weekend Brooklyn Pride PRIDEChicago Cincinnati Week of Pride Dayton Pride Erie Pride 2013 Parade Florianopolis Pride Guadalajara Gay Pride Honolulu Gay Pride Kansas City Pride Festival Statewide March Long Island Pride Mexico Pride March Swing for Pride Women’s New Hope Celebrates Albany, N.Y., U.S.A. Jul 20 TBD TBD Jun 28 - 30 Jun 29 TBD & Rally TBD TBD Jun 1 TBD Aug 24 Jun 8 TBD Golf Tournament Pride Capital Pride 2013 TBD TBD TBD May 30 - Jun 9 Atlanta, Ga., U.S.A. Bogota, Colombia Buenos Aires, Argentina Chicago, Ill., U.S.A. Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A. Denver, Colo., U.S.A. Fort Collins, Colo., U.S.A. Guadalajara, Mexico Houston, Texas, U.S.A. Key West, Fla., U.S.A. Las Vegas, Nev., U.S.A. Los Angeles, Calif., U.S.A. Miami, Fla., U.S.A. Atlanta Pride Bogota Gay Pride Buenos Aires Pride Northalsted Market Days Cleveland Pride Denver PrideFest 2013 Eugene, Ore., U.S.A. Fort Collins PrideFest 2013 International LGBT Pride Houston Bone Island Weekend Gay Days Las Vegas Primetime White Party Week Monterrey, Mexico New Orleans, La., U.S.A. -

Pride Festival Buenos Aires, Argentina Texas Freedom Parade TBD TBD July 14 TBD U.S.A

Major LGBT Global Events Updated December 1, 2013 Boston, Mass., U.S.A. Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A. Fire Island, N.Y., U.S.A. Humboldt, Calif., U.S.A. AMERICAS Boston Youth Pride 2014 Cleveland Pride Ascension Fire Island Humboldt Pride Parade Albany, N.Y., U.S.A. TBD Jun 28 TBD and Festival Capital Pride 2014 May 28 – Jun 8 Boston, Mass., U.S.A. Colorado Springs, Colo., Flagstaff, Ariz., U.S.A. TBD Latino Pride 2014 U.S.A. Pride in the Pines Indianapolis, Ind., U.S.A. Albany, N.Y., U.S.A. TBD Colorado Springs TBD Indy Pride Say It Loud! Black and Pride 2014 TBD Latino Gay Pride Boston, Mass., U.S.A. TBD Florianopolis, Brazil TBD Boston Dyke March Florianopolis Pride Indianapolis, Ind., U.S.A. Jun 13 Columbia, S.C., U.S.A. Feb 28 - Mar 5 Indiana Black Gay Pride Albuquerque, N.M., U.S.A. South Carolina Pride TBD Albuquerque Pride Boulder, Colo., U.S.A. Festival Fort Collins, Colo., U.S.A. Jun 31 Boulder PrideFest TBD Fort Collins PrideFest 2014 Jackson, Miss., U.S.A. TBD TBD Jackson Black Pride Allentown, Pa., U.S.A. Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A. TBD Pride in the Park 2014 Butte, Mont., U.S.A. Columbus Gay Pride Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Long Island, NY, U.S.A. Moncton, Canada Oklahoma City, Okla., Provincetown, Mass., San Antonio, Texas, U.S.A. Spencer, Ind., U.S.A. Bucharest, Romania Helsinki, Finland Munich, Germany Siegen, Germany Mumbai, India TBD Montana Pride Jun 20 – 21 U.S.A. -

Squatters Pub Brewery Epic Brewing Company

SaltLakeUnderGround 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround SaltLakeUnderGround 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 22• Issue # 270 • June 2011 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Shauna Brennan Editor: Angela H. Brown [email protected] Managing Editor: Jeanette D. Moses Sales Coordinator: Shauna Brennan Contributing Editor: Ricky Vigil Marketing Coordinator: Editorial Assistant: Esther Meroño Bethany Fischer Office Coordinator: Gavin Sheehan Marketing: Ischa Buchanan, Jeanette D. Moses, Jessica Davis, Hailee Jacob- Copy Editing Team: Jeanette D. son, Stephanie Buschardt, Giselle Vick- Moses, Rebecca Vernon, Ricky Vigil, ery, Veg Vollum, Emily Burkhart, Rachel Esther Meroño, Liz Phillips, Katie Pan- Roller, Jeremy Riley, Sabrina Costello, zer, Rio Connelly, Alexander Ortega, Taylor Hunsaker, Tom Espinoza Mary Enge, NWFP, Cody Kirkland, Hannah Christian Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Cover Design: Travis Bone Tony Bassett, Joe Jewkes, Jesse Hawl- Issue Design: Joshua Joye ish, Nancy Burkhart, Joyce Bennett, Design Interns: Eric Sapp, Bob Adam Okeefe, Ryan Worwood, David Plumb, Jeremy Riley, Chris Swainston Frohlich, Tom Espinoza Ad Designers: Todd Powelson, Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Lio- Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, nel WIlliams, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Mariah Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Tompkins, Maggie Poulton, Eric Sapp, Lance Saunders, Jeanette D. Moses, Brad Barker, KJ, Lindsey Morris, Paden Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Ben- Bischoff, Maggie Zukowski, Thy Doan nett, Ricky Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, -

Utah's Gay Community Reels Over Suicides Lagoon Day Expected To

Utah’s News & Entertainment Magazine for the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Community | FREE salt lake Issue 160 August 5, 2010 My Last Shot Jailed on Christmas Day, a Man’s Battle to Overcome Meth Utah’s Gay Lagoon Day Rally will Call for Park Silly Community Reels Expected to Be Gay Community will be over Suicides Largest Ever Evolvement Gay for a Day Q staff You NEED a publisher/editor Michael Aaron assistant editor JoSelle Vanderhooft ISSUE 160 • Aug 5, 2010 arts & entertainment Bigger Audience editor Tony Hobday graphic designer Christian Allred ... and we NEED YOU crystal meth contributors Chris Azzopardi, Lynn My Last ‘Shot’ with Meth ......... 27 Beltran, Turner Bitton, Dave Brousseau, Brad Di Iorio, Chef Drew Ellswroth, Greg Crystal Meth in Utah ............. 27 Fox, H. Rachelle Graham, Bob Henline, Tony Hobday, Christopher Katis, Keith Orr, Petunia Pap-Smear, Anthony Paull, The choir is growing larger and news Steven Petrow, Hunter Richardson, Ruby National ........................ 6 Ridge, Ryan Shattuck, A.E. Storm, JoSelle sounding better every concert. Vanderhooft, Ben Williams, Troy Williams, e nal reason to love the Local ........................... 8 D’Anne Witkowski, Rex Wockner You’ve never met a better contributing photographers Ted Berger, views Eric Ethington, Honey Rachelle Graham, ® group of guys Come rehearse First Person ......................4 Chris Lemon, Brent Marrott, Carlos Navales, Scott Perry, Deb Rosenberg, 2010 Deer Valley Music Festival with us on Thursdays and see Editorial Cartoon ................ 14 Chuck Wilson what it’s all about! Letters ......................... 14 sales manager Brad Di Iorio Guest Editorials ................. 15 office manager Tony Hobday Queer Gnosis ................... 16 distribution Brad Di Iorio, Ryan Benson, Gary Horenkamp, Nancy Burkhart The Straight Line ............... -

2018 Marked the Release of the Long-An�Cipated Sophomore Album from Steve Grand, Not the End of Me

About July 6, 2018 marked the release of the long-an:cipated sophomore album from Steve Grand, not the end of me. It hit #2 on the iTunes Pop Chart, #10 on Billboard's Independent Album Chart, and #78 on Billboard’s Top Album Chart. It was released independently on his own label, Grand Na:on LLC. The album includes 12 new tracks, all wriPen and composed by Grand. It also features alternate versions of 3 of the songs. Grand says of the tracks, “This album is autobiographical; very personal, somber and reflec:ve.” “Wri:ng this album was an exercise in catharsis,” says Grand. “I’m more unfiltered on this album and explore some of the internal and external challenges I’ve faced over the last few years.” The album's :tle track, "not the end of me", is a song Grand wrote when a long-:me rela:onship was coming to an end. "Breaking up can be long and drawn-out, painful and ugly. This one certainly was," Grand said. "It was trying and exhaus:ng, (and) this song deals with all of that, as well as the resolu:on that this is 'not the end of me." Grand also predicts "don't let the light in" will be a favorite among his fans. "I wrote it within the last few months before I became sober. At that :me, I was reflec:ng on the way I had been living my life over the last few years that my song 'All-American Boy' blew up, in 2013," he said. -

The Effects of the Political Landscape on Social Movement Organization Tactical Choices

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2012 The Effects of the Political Landscape on Social Movement Organization Tactical Choices Jennifer Marie Swalboski Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Swalboski, Jennifer Marie, "The Effects of the Political Landscape on Social Movement Organization Tactical Choices" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1303. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1303 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTS OF THE POLITICAL LANDSCAPE ON SOCIAL MOVEMENT ORGANIZATION TACTICAL CHOICES by Jennifer M. Swalboski A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Sociology Approved: Douglas Jackson-Smith E. Helen Berry Major Professor Committee Member Leon Anderson Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 ii Copyright © Jennifer Swalboski 2012 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The Effects of the Political Landscape on Social Movement Organization Tactical Choice by Jennifer M. Swalboski, Master of Science Utah State University, 2012 Major Professor: Dr. Douglas Jackson-Smith Department: Sociology The majority of sociological research on social movement tactics and strategies has focused on how theories of resource mobilization and dynamic political opportunities affect the innovation of tactics and types of tactics used. -

Pride and Prejudice

PRIDE REDUX Pictures from PrideFest and the Milwaukee Pride Parade. page 19 THE VOICE OF PROGRESS FOR WISCOnsin’s LGBT COMMUNITY June 13, 2013 | Vol. 4, No. 16 Marriage rulings imminent By Lisa Neff fornia’s Proposition 8, the state’s woman, and to the U.S. Defense of Staff writer voter-approved constitutional Marriage Act, which defines mar- The U.S. Supreme Court is amendment defining marriage as riage as the union of a man and a expected to issue opinions in two the union of a woman for federal purposes. cases this month that – in the best man WiG looks at the cases, the possible outcome – could clear the and a issues, the court, the potential way for same-sex couples to marry outcomes and the history of the throughout the United States, thus pursuit of marriage equality. allowing those couples to access more than 1,100 federal benefits associated with marriage. The justices in March heard arguments in challenges to Cali- page 14 Pride and prejudice PHOTO: AP/CHINaTOPIX Globally, LGBT celebrants face assault and worse By Lisa Neff Chinese activists kiss as they take Staff writer part in a gay Pride parade in Chang- In cities, provinces and entire countries sha in south China’s Hunan prov- around the world, LGBT Pride event orga- ince on May 17. nizers risk becoming political prisoners and Pride celebrants risk becoming trauma patients. “In some places, especially the United States where it all started, Pride is a celebra- tion of how much progress has been made,” said Zurich-based human rights activist Anna Gomes. -

Guide to the DC Cowboys Dance Company Records

Guide to the DC Cowboys Dance Company Records NMAH.AC.1312 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2014 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Company Files, 1994 - 2013, undated..................................................... 5 Series 2: Financial, 1996 - 2011, undated............................................................. 21 Series 3: Audio-visual Materials, 1994 - 2012, undated........................................ 23 DC Cowboys Dance Company Records NMAH.AC.1312 Collection Overview Repository: Archives -

Steve Grand Broke the Mold for the Traditional Singer-Songwriter

About With over 18 million views on YouTube, a #3 and #10 album on The Billboard Independent A l b u m c h a r t s , a n d o n e o f t h e m o s t successful music Kickstarter campaigns ever under his belt, Grand has not just broken the rules, but has changed the game in how to be a successful singer-songwriter in this era. With the release of his first album, All American Boy, in 2015, Steve Grand broke the mold for the traditional singer-songwriter. Having self-funded a viral video of the title track, then fan funding the release and creating a vocal and energetic fanbase, the openly gay artist from Chicago created a place for himself in the music industry and hasn’t looked back since. Highlights • “Not The End of Me” (New CD debuted July 6, 2018) album hit #2 on iTunes Pop Chart, #10 on Billboard’s Independent Albums Chart & #78 on Billboards Top Albums Chart • Had the #3 Most Funded Music Project in Kickstarter’s History with over 5000 backers • 7M+ view of “All American Boy” video and 17M+ combined views on YouTube • “All American Boy” debuted in 2015 at #47 on the Billboard top 200 and #3 on the Billboard Independent album chart Socials Combined Social Media Following of over 750K+ Facebook: 275K+ Likes Instagram: 242K+ Followers Twitter: 57.3K+ followers YouTube: 190K+ subscribers // 17.4M+ views Highlights Residencies Provincetown, MA - The Art House Previous Pride Events July - September 2017 July - September 2018 • Nashville Pride • Utah Pride Festival • Long Island Pride • Toronto Pride Puerta Vallarta - Red Room Cabaret • Boise Pride • Knoxville Pride Fest December 2017 • • Miami Beach Pride St.