Ethics of Emerging Media Iv V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A-1 Layout 1

Deer Hunt S UBSCRIBE ONLINE AT Kids: Free Ticket ‘Til March 2 THEHERALDADVOCATE.COM To State Fair . Column 12A . Story 10A The Herald-Advocate Hardee County’s Hometown Coverage 114th Year, No. 10 3 Sections, 32 Pages 70¢ Plus 5¢ Sales Tax Thursday, February 6, 2014 Boyfriend Charged In Baby’s Murder By CYNTHIA KRAHL Wauchula, has been charged Attorney’s Office, jury members permanent disability or perma- Rivera, 22, the baby’s mother, A Hardee County Grand Jury with first-degree murder and ag- agreed there was sufficient nent disfigurement.” are currently being held in the has handed up a murder indict- gravated child abuse in the Nov. cause to charge Jaimes with cap- It further accused Jaimes of Hardee County Jail on other, but ment against the boyfriend of a 5 death of 15-month-old Joel ital-felony murder and first-de- causing such “trauma to the similar, charges. Both had been woman whose baby was pro- Jordan Chavez. gree-felony abuse. head and body” of the baby be- arrested on Nov. 6 on a felony nounced dead by an Emergency Grand jurors delivered the in- Their indictment alleges that tween Nov. 4 and Nov. 5 to count of child neglect after Room doctor. dictment on Friday. between Oct. 1 and Nov. 5, cause his death “from a premed- officers investigating Joel’s Hector Tavera Jaimes, 24, of After hearing testimony and Jaimes abused Joel to the point itated design.” death allegedly disco- 310 W. Townsend St., evidence presented by the State of causing “great bodily harm, Jaimes and Kaycha Lynn See MURDER 2A Brant BRAVE BEAUTIES Jaimes Avoids Man, 81, Prison Accused Of By CYNTHIA KRAHL Of The Herald-Advocate A former city commissioner and funeral director has avoided Attempted prison and been sentenced to a lengthy probation following charges he defrauded a number of clients. -

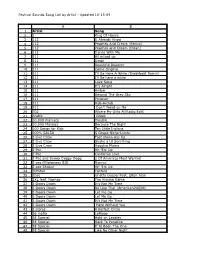

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Committee Oks Bergin's As Landmark

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • WeHo considers budget. pg. 3 Partly cloudy, • Alan Arkin with highs in honored pg. 12 the mid 70s Volume 29 No. 24 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hancock Park and Wilshire Communities June 13, 2019 La Brea Tar Pits next on Thousands #JustUnite in West Hollywood Museum Row revamp n Organizers will now look ahead to next By edwin folven ed is poised to undergo major year’s landmark 50th changes in the coming years. Black liquid tar has been bub- Dr. Lori Bettison-Varga, presi- anniversary of Pride bling up through the Earth’s surface dent and director of the Natural near present-day Wilshire History Museums of Los Angeles By luke harold Boulevard and Curson Avenue for County, which oversees operations millions of years. With that history at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum Under the theme #JustUnite, and its scientific importance in (formerly the George C. Page thousands of people attended the mind, the famous site where La 49th annual LA Pride festival Brea Tar Pits and Museum is locat- See Tar Pits page 26 and parade June 8-9 in West Hollywood. The celebration started Friday with a free ceremony and concert in West Hollywood Park head- lined by Paula Abdul. Festival- goers flooded the park and San Vicente Boulevard Saturday and Sunday to see a musical lineup photo by Luke Harold including Meghan Trainor, Pride was on parade Sunday morning, with local council members, law Ashanti and Years & Years. enforcement, corporate sponsors and other groups riding in floats. “Pride has been something I’ve wanted to play for a long just have a good time.” Angeles City Councilman Mitch time,” said Saro, a recording The annual Pride events have O’Farrell on a float during artist who performed in the Pride become a joyous celebration Sunday’s parade. -

July 2009 Nypress

A Message from Dr. Pardes and Dr. Corwin We would like to thank and New York-Presbyterian congratulate all of you for your The University Hospital of Columbia and Cornell energy and support throughout our NYP unannounced Joint Commission 4HENEWSLETTERFOREMPLOYEESANDFRIENDSOF.EW9ORK 0RESBYTERIAN!"##6OLUME )SSUE*ULY Mock Survey last month. NYP performed very well and the surveyors recognized our commitment to providing the highest quality and safest care to our patients and families. They were extremely impressed with the compassion Prom Night - and engagement of our staff, nurses and physicians; and they hen the calendar flips to June, teenagers across the coun recognized Patient Safety Fridays as try can barely contain their excitement as the school year a best practice and model that other W comes to an end. For many, it will mean graduation and the hospitals across the country are beginning of a new chapter in their lives. But before they reach that adopting. milestone, there is another rite of passagee a patient waiting in the for hospital them: theduring prom. It’s July and that means we will But what happens when you’r be conducting our annual Employee Despite chronic and life-threatening illnesses, about 40 prom season? Survey — one of the ways we can determined teenage patients at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley bring about positive change at Children’s Hospital decided they would not let their prom night go NYP. We really count on everyone’s uncelebrated. participation in this confidential On June 6, dressed to the nines in gowns and tuxedos, the patients process so that improvements can be turned the Hospital’s Wintergarden into their own private ballroom, made across the Institution. -

Stapleton Welcomes the Urban Land Institute

Distributed to the Greater Stapleton Area DENVER, COLORADO OCTOBER 2006 Stapleton Welcomes The Urban Land Institute When several thousand delegates from throughout the nation and around the world into one of the nation’s premier new urban communities will have a prominent role in the gather in Denver this month to attend the 2006 fall meeting of The Urban Land spotlight. The Urban Land Institute is one of the world’s most respected advocates for Institute (ULI), the transformation of Denver’s former Stapleton International Airport sound land use and smart growth. (See John Lehigh column on page three.) Stapleton Family Shares Adoption Story Roberts Family Gathers By Kathy Epperson not often discussed, those who explore this opportunity he decision to adopt a child is significant, emotional quickly hear the stories of other adoptive parents and for School Dedication and inspired by different circumstances. Some discover tremendous support from many great resources. Tchoose to adopt after struggling to conceive a child. What follows is an interview with Stapleton residents Others feel a calling to provide a loving home for an Emily and Mark Barr, who already had three biological kids orphan. And for some families, fate may conspire to bring a when they decided to adopt two children from Ethiopia this particular child into their lives. While adoption is a subject year. Emily, who works in the HIV/AIDS clinic at Children’s Hospital, was already familiar with the HIV/AIDS crisis in Africa and the alarming number of children left without parents. We also tell the story of one young Ethiopian girl recently adopted by a Denver family who hopes to find adoptive parents for her younger brother and sister who were left behind. -

Downey Latina Chasing Her Dreams

Little boy More support Egg hunt a has big heart for GOOD blast for kids See Page 7 See Page 12 See Page 7 Friday, April 17, 2009 Vol. 7 No. 52 8301 E. Florence Ave., Suite 100, Downey, CA 90240 Downey Latina DMOA and chasing her dreams Davies sued by former associate BY ERIC PIERCE, Jennifer’s sister, said. “I am CITY EDITOR blessed to have such a compassion- ate and talented sister in my life Former business director alleges fraud, breach of DOWNEY – “American Idol” and am thankful that she has been isn’t the only hit television show to able to covey her talent to viewers contract in lawsuit. feature a rising star from Downey. across the nation.” Former Miss Downey Princess Andrade, 20, attended Gallatin tract and fraud, allegations against BY HENRY VENERACION, Jennifer Andrade is competing on Elementary, East Middle School, DMOA and Davies include unfair STAFF WRITER the current season of “Nuestra and graduated from Downey High business practices. Belleza Latina,” a Spanish-lan- School in 2006. She made Downey As director of business and DOWNEY – The Downey guage beauty competition – “with a High’s varsity cheer squad as a development, McGarr’s duties Museum of Art (DMOA) and its reality TV twist” – now airing on freshman and also played JV water included, but were not limited to, director, Kate Davies, are being Univision. polo. business and program develop- sued by its one-time director of Andrade left for tapings in In 2004, Andrade competed for ment, negotiations of program business and development, Anita Miami on March 1, family mem- Miss Teen Downey -- her first pag- and/or project contracts and agree- McGarr, for breach of contract and bers said. -

August 2008 New

“To have been given this opportunity and to be able to share music with people is just the best feeling ever.” ST —David Archuleta JU D avid Archuleta, a 17-year-old from Murray, Utah, a town A Dcentered in the Salt Lake Valley, made it as one of the top two on American Idol, a television V singing competition. BY JANET THOMAS In one interview given while I Church Magazines in the middle of the competi- D tion, David was wondering about the changes that were coming with the fame of performing for millions of viewers each week. He said that he still felt like “I’m just David from Murray.” him as you saw on the The nation may have been surprised to hear show. That’s how he really is.” such a pure, clear voice coming from one so Was David the popular guy in school? young, but David’s classmates at school, and Jessica Judd, another of David’s friends says, especially those in seminary, were not surprised “If by popular you mean people like him, then at all. They already knew he had an amazing yes, everyone likes him. At lunch, you know voice because they get to hear him sing at how everyone has their own group to sit with. school programs and for seminary devotionals. You can never find David because he’s going Fellow contestant “Every time it’s his turn to do the class around talking to people. He cares about you.” and Church member devotional,” says Brother Justin Harper of the The Church is a major force in David’s life. -

5 Million Gift from the Building and Construction Trades Department, Afl-Cio

Diabetes Research Institute Foundation Summer 2010 / Volume 37 / Issue 2 Miami / New York / Long Island / California / Washington, D.C. DRI ocus fJoin us on social media sites! Diabetes Research Institute Foundation Receives $5 MILLION GIFT FROM THE BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION TRADES DEPARTMENT, AFL-CIO The Diabetes Research Institute Foundation’s largest contributor, the Building and Construction Trades Department (BCTD) of the AFL-CIO, has pledged $5 million to be awarded over five years. This new gift brings the total dollars raised to more than $45 million over the last 25 years and firmly cements the unions’ commitment to help the Diabetes Research Institute find a cure for diabetes. According to Building and Construction Trades Department President Mark Ayers , the construction industry has been hit particularly hard by the decline in the economy, yet NEW Website, NEW Look, he attests that now is not the time to step away from the BCTD's commitment. MORE Features! “This dreadful disease continues to have a profound impact on people’s lives in Have you visited DiabetesResearch.org lately? If so, good times and in bad. Our members across the country subscribe to the belief that you’ve seen that we have completely redesigned ‘tough times never last – but tough people do,’ and our commitment to finding a our website to make it more dynamic and user- cure is enduring and unwavering,” said President Ayers. “We’ve come too far to friendly. After a year of development, the new site turn back now.” was launched with many new features and tools to offer a better experience and more information Continued on Page 3 for our visitors. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

American Idol Vets Star in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

American Idol Vets Star in Joseph and The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat Ace Young and Diana DeGarmo are starring in the touring company of the smash musical Joseph and The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, which will be performed at the Providence Performing Arts Center (PPAC) from November 4 through 9. Young, who plays the lead role of Joseph, and DeGarmo, who plays the narrator, got their big break on the smash television singing competition, “American Idol.” DeGarmo was the runner-up on the show’s third season. Young was on the fifth season, where he finished seventh. Composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyricist Tim Rice teamed up to bring Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat to life. The story is based on the “coat of many colors” story of Joseph from the Book of Genesis. The show is directed and choreographed by Tony® Award-winner Andy Blankenbuehler. The chance to work on a stage production together had tremendous appeal to DeGarmo and Young, who are married. “It’s such a rare opportunity in this industry to work on a show that’s family friendly,” DeGarmo told Motif. “It’s a beloved story, a beloved show. I truly believe it’s one of the classics.” “This is definitely a dream come true (for DeGarmo),” Young said, noting DeGarmo always wanted to play the narrator in the show. Young is proud to be part of a show that appeals to the “American Idol” fan base, which ranges from young children to senior citizens. “It’s a really great show about second chances and family and the true meaning of friendship,” Young said, noting the show’s high spirits are infectious: “Everyone’s on their feet having a blast with us.” DeGarmo and Young have been very busy since their days on American Idol. -

C. Post-Idols - (1) Dctr Era ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ C. POST-IDOLS - (1) DCTR ERA ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ EVENTS ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 79TH ANNUAL PLAZA LIGHTING CEREMONY - KANSAS CITY, MO y (NOV 27, 2008) Videos: Ź Playlist KCTV-5 Interview with David Cook | American Idol David Cook Flips switch | David Cook Sings medley with Andrew and the crowd AMERICAN IDOL EXPERIENCE - WALT DISNEY WORLD y (FEB 12, 2009) GALA OPENING - DISNEYWORLD - Hollywood Studios, CA Opening Show Video(s): Ź Playlist 01 Full Show (Pt 4 of 4) | 02 David Cook sings - Light On (Acoustic) | 03 Awards given to 7 past American Idol winners & Dream Ticket winner announced | 04 Carrie Underwood Sings | 05 David Cook & Carrie Underwood Duet - Go Your Own Way / Interview Video(s): Ź Playlist AI Experience Feature (w short interviews) | I Experience Gala Opening - Fox Orlando | David Cook Blue Carpet interview | Idols Interviews -AI Experience (Charlie Belcher) | KISS FM 102.7 - Ryan Seacrest | ž Orlando Sentinel - AI David Cook displays his humor | źDavid Cook interview at Disney | David Cook Taste of stardom (short part w David) | E! Online - Idols interviews | ET Online - Idols Unite / Misc Video(s): Ź Playlist AI Experience World Premiere Photoshoot | Archuleta, Cook & Underwood on Disney's Rock n Roller Coaster | David Cook at Disney's -

• Ws/Story?Id=6456834&Page=1 WHAT IS SEXTING?

• http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/WorldNe ws/story?id=6456834&page=1 WHAT IS SEXTING? • The newly minted word for sending or posting nude or semi-nude photos or videos WHY ARE KIDS SEXTING? • 82.2% said to get attention • 66.3% said to be “cool” • • 59.4% said to be like the popular girls • 54.8% said to find a boyfriend WHY ARE KIDS SEXTING? • Peer pressure ( 52%-Boys) (23%-Friend) • Revenge after a breakup • Blackmail • Flirting • Impulsive behavior • Special present • Joke • Think it will remain private What Did the World Do Before Cell Phones and Texting? • You got your stuff done on time. • Kids talked to their parents in person. • We used quarters at pay telephones. • Parents owned cameras that took photos. • People used complete words, not BFF, LOL, OMG, or . • Wrote personal letters and mailed them with a licked stamp. • IM had an apostrophe (I’m). • 1 out of 5 teens have sent nude or semi nude pictures or videos of themselves • 40% of teens have had a sexually suggestive message shown to them • 71% of teen girls and 67% of teen guys who have sent sexually suggestive content say they have sent this to a boyfriend/girlfriend • 44% of teens say it is common for these messages to get shared with people other than the intended recipient Why do teens send these messages? • Pressure from guys • Pressure from friends • As a joke • “Fun or flirtatious” • “Feel sexy” or as a “sexy present” • To bully or harass • To get attention Potential Consequences • Future employment and college admission may be jeopardized • Relationship problems • Mental health issues/Suicide • Violate school rules • Legal issues • http://www.thatsnotcool.com/TVSpot.aspx THE LAW • The legal system is lagging behind technological advances.