Messages – the Radiogram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Radiogram

The August 2013 ~ Official Newsletter of the Portage County Amateur Radio Service, Inc. (PCARS) ~ Vol. 8 No. 8 ~ 2013 Officers ~ From the President In his inauguration speech on Friday, January 20, 1961, President John F. Kennedy said “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can K3GP N8QE WB9LBI KD8JCY - - AE8YL do for your country.” That line has been quoted often. (The whole speech was actually very - - - good, you can read it at http://www.bartleby.com/124/pres56.html ) As PCARS continues to WB8LCD - Pelz grow, we are in a similar situation in that with all the programs and activities we have for the benefit of all members, we need more members Erica Bob HajdakBob - - to be involved with the operation of the programs Sandra Getty Bill FraedrichBill Tom Sly - - - and activities of the club. Right now, there are George Proudfoot - some people in the club who do an awful lot of the “heavy lifting” that has to be done to keep an President Year Trustee organization of our size moving. None of them 3 2 Year Trustee Treasurer do so grudgingly, they all do it as an act of giving 1 Year Trustee Vice President back to a great hobby that has given them untold ~ Meetings & Net ~ hours of fascination and enjoyment. I want to ask each one of you to look at all the activities of the club and see if there is not a spot Net at 8 pm where you could “plug in” and help out. -

New Zealand DX Times Monthly Journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (Est 1948) D X April 2013 Volume 65 Number 6 LEAGUE LEAGUE

N.Z. RADIO N.Z. RADIO New Zealand DX Times Monthly Journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (est 1948) D X April 2013 Volume 65 Number 6 LEAGUE http://www.radiodx.com LEAGUE NZ RADIO DX LEAGUE 65TH ANNIVERSARY REPORT AND PHOTOS ON PAGE 36 AND THE DX LEAGUE YAHOO GROUP PAGE http://groups.yahoo.com/group/dxdialog/ Deadline for next issue is Wed 1st May 2013 . P.O. Box 39-596, Howick, Manukau 2145 Mangawhai Convention attendees CONTENTS FRONT COVER more photos page 34 Bandwatch Under 9 4 with Ken Baird Bandwatch Over 9 8 with Kelvin Brayshaw OTHER English in Time Order 12 with Yuri Muzyka Shortwave Report 14 Mangawhai Convention 36 with Ian Cattermole Report and photos Utilities 19 with Bryan Clark with Arthur De Maine TV/FM News and DX 21 On the Shortwaves 44 with Adam Claydon by Jerry Berg Mailbag 29 with Theo Donnelly Broadcast News 31 with Bryan Clark ADCOM News 36 with Bryan Clark Branch News 43 with Chief Editor NEW ZEALAND RADIO DX LEAGUE (Inc) We are able to accept VISA or Mastercard (only The New Zealand Radio DX League (Inc) is a non- for International members) profit organisation founded in 1948 with the main Contact Treasurer for more details. aim of promoting the hobby of Radio DXing. The NZRDXL is administered from Auckland Club Magazine by NZRDXL AdCom, P.O. Box 39-596, Howick, The NZ DX Times. Published monthly. Manukau 2145, NEW ZEALAND Registered publication. ISSN 0110-3636 Patron Frank Glen [email protected] Printed by ProCopy Ltd, President Bryan Clark [email protected] Wellington Vice President David Norrie [email protected] http://www.procopy.co.nz/ © All material contained within this magazine is copy- National Treasurer Phil van de Paverd right to the New Zealand Radio DX League and may [email protected] not be used without written permission (which is here- by granted to exchange DX magazines). -

Hoppy Easter 2021

THE WAVES AND FIELDS OF THE RADIO ARTS W5SLA OZONE AMATEUR RADIO CLUB SINCE 1964 VOLUME'S 2021 V & VI http://www.coastalradio.org.uk/worldcoastal/slidellradio/slidell.htm Based on conversations with “Emile, thanks for the email. I'll try and answer some of your questions and give you some insight AA5UY, I found out about a into the workings of the old WNU. I retired from the Coast Guard on 1 October 1980. I did a little local with a history from the commercial painting but got tired of that and got my 3rd class license and went to work at WNU in station in Slidell, LA. I wrote to June of 1981. I was there until June of 1993. What a neat job. Getting paid to play. When I first got Mr. Beith and got this reply. there, we had about 20 Radio Officers and maybe 15 teletype workers.(I think they were known as IPOs - international printer ops). Received messages went directly to the printer ops for delivery. Business was good and most of the R/O's got 80 to 100+ messages per watch during the day. We SHOUT OUT TO had about 8 ops on duty during the day 4 during the evening and 1 on the mid. As the years went by Club Member our manpower shrunk and so did the traffic. In 1993 WNU sold out to KFS (in California) and remoted all operations to the west coast. I was the last operator on duty when they turned KD5PCK – Scott operations over to the new group. -

Wireless-World-1967

DOMESTIC TECHNIQUES OCTOBERThree Shillings 1967 Wireless World OCTOBER, 1917 or your circuit, with built-in ripp,11 assembled units courtesy of South London Electrical Equipment Co. Ltd. We've got the biggest little chassis in town SAVE TIME & MONEY with precision -built Keyswitch optional Keyswitch printed -circuit board withits I plug-in chassis. They're the ideal way to put a hand- mounting -hole grid backed by interconnecting cop- ful of circuitry together, and not necessarily a small per strips, you have an infinite variety of circuit and handful either. Even relays and small motors can be layout possibilities. And all this for as little as 15/- a mounted in these versatile units. Here's your choice time, from Keyswitch Relays Ltd, 120 Cricklewood of mounting space: Lane, London NW2; telephone 01-452 3344; telex Keyswitch P304S - 51i n3 262754. Keyswitch P304 (illustrated) - 71in3 Keyswitch 2P304 (with 44 -way connectors) - 15in3 milkilTMITVITCH1RELAYS Whether you use your own mounting board, or the WW -001 FOR FURTHER DETAILS -79 Editor -in -chief: Wireless World W. T. COCKING, F.I.E.E. Editor: H. W. BARNARD ELECTRONICS, TELEVISION, RADIO, AUDIO Technical Editor: T. E. IVALL OCTOBER 1 9 6 7 Editorial: B. S. CRANK 463 What is the Electronics Industry? F. MILLS 464Domestic Receiver Techniques G. B. SHORTER, B.sc. 472Stereo Signal Simulator by D. E. O'N. Waddington 476 Drawing Office: Colour TV Standards Converter H. J. COOKE 482 Semi -stabilized D.C. Supply by G. W. Short 483German Colour Television Starts Proauction: 488 Wireless World Digital Computer -3 D. R. BRAY 496 New Measurement Techniques Advertisements: 500 Colour TV Circuit Round -up by T. -

The RADIOGRAM – May 2013 – Page 1 of 28

The May 2013 ~ Official Newsletter of the Portage County Amateur Radio Service, Inc. (PCARS) ~ Vol. 8 No. 5 ~ 2013 Officers ~ From the President In the May issue of QST magazine, there is a letter to the Editor from NT4I in which he states: “I am personally disgusted with what I hear on the air and have made the decision to K3GP N8QE WB9LBI KD8JCY - - AE8YL sell my equipment, stop operating and find a new hobby. In part, I blame the ARRL for - - - supporting how simple and easy it is to obtain a license. While the ARRL may puff its chest WB8LCD - Pelz that the numbers are at an all time high, I feel that the quality of the licensee is at an all time low!” Erica Bob HajdakBob - - Sandra Getty Bill FraedrichBill Tom Sly - - - I say, with Mr. Cammarata gone, the quality of the average licensee has just risen. George Proudfoot - Looking up his call on QRZ.com I find he's had a lot of lookups (if that means anything) but sident no other information. There is a photo, which I presume is a self-portrait. Next I went to the President Year Trustee ARRL website to see how many VE sessions he had participated in – 0. Goose egg. Nada. 3 2 Year Trustee Treasurer Zip. I did a google search on his call sign. Same thing, little or no information. It appears 1 Year Trustee Vice Pre that Mr. Cammarata has not been an active participant in anything that would be for the ~ Meetings & Net ~ betterment of Amateur Radio. -

A Two Valve Portable Radiogram 1

A TWO VALVE PORTABLE RADIOGRAM 1 sg, - CONTENTS A SIMPLE INTER -COM INCREASING T.R.F. SELECTIVITY A MICROPHONE PRE -AMPLIFIER A TRANSISTORISED SIGNAL GENERATOR FURTHER MODULATION ASPECTS www.americanradiohistory.com PRACTICAL WIRELESS March, 1958 C.R.T. ISOLATION TRANSFORMER CHAMPION VHF (FMI TUNER, Type A. Low leakage windings. Ratio 1:1.25 88 -96 me /s. giving a 25/, boost on secondary . 5 Mullard valves and superhet tuning heart. ; 4 v. ; 6.3 v., 10/6 ; 10.8 v.. 10/6 10/6 Maroon and cream receiver styled cabinet. 10,6 ; 13.3 v., 10/6. 12 u u x tiln. FMlures: This ie a self -powered Ditto with mains primaries, 12/8 each. 200/250 t. C VHF (FM) Adaptor with Mains 221/740 t vt Type B. input volts. Multi opensting and servicing data and a screened Output 2, 4, 6.3, 7.3, 10 and 13 volts. Input lead for connect- to pick -up sockets ut any has two taps which increase output volte by radio, radio-gmm or amplifier. 25';, and 50% respectively. Low capacity brand flew with 12 months'iths' guarantee. List imitable for most Cathode Ray Tubes, 211 - Ditto for 6 v. C.R. Tubes only- 17/0 price, In gee Our price. ..arr. 416. Type C. Low capacity wound transformer for 10 gns., of 81 use with 2 volt Tubes with falling emission. Term+: l lepe oit £8 and 6 monthly payments Input 220/240 volte. Output 2.2 }02} 21 -3 volts at 2 amps. Tag Panel, 17/6 each. With 1958 RADIOGRAM CHASSIS Volume Controls t COAX NOTE.-It Is essential to use mains primary 80 ABLI. -

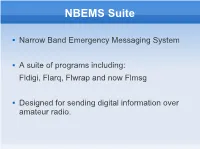

Fldigi Basics

NBEMS Suite Narrow Band Emergency Messaging System A suite of programs including: Fldigi, Flarq, Flwrap and now Flmsg Designed for sending digital information over amateur radio. Install Fldigi - Flwrap - Flmsg Available for Windows, Mac and Linux CD – Handed out Pre-installed Wireless Download - NHARES Access point - http://192.168.1.2 - Follow the nhares directory structure NH-ARES Digital Primer What is ”Digital Communications” in amateur radio? What is the best mode? How do you interface the radio and computer? What information can be sent over digital? What information should be sent over digital? HF vs. VHF/UHF Use on simplex or repeaters? Digial Communications: ANY information that can be digitized can be sent via a digital mode. Some data is just too big to reasonably send via sound card digital modes (Video, MP3, big pictures) etc. We will be focusing on smaller file types: text, spreadsheets in .csv format, small pictures. Information that SHOULD be sent via digital: Any ”sensitive” information such as phone numbers, names, etc. Specific directions / instructions. Long lists of information. Difficult to spell names. Prescriptions. Others????? Information that SHOULD NOT be Sent via Digital Modes: Quick exchanges of simple information. Simple status updates. Station call-ups – basic Net operation. Others? Digital Communications Using FLDIGI What is fldigi?? Available for Windows, Mac and Linux Can be used as a ”live cd/USB” with the Puppy Linux version, Ubuntu and others Sound Card Modes Which mode to choose? Contestia, DominoEX, Hell, MFSK, MT63, Olivia, Psk, RTTY, Thor, Throb There are many different variation of these modes: Example PSK31, PSK31R, PSK63, PSK125, PSK250, PSK500 Which Mode? Which Mode? Which Mode? Which Mode? Which Mode? Old School Digital Operating Required a sound card interface. -

An Introduction to HF Communications What Is “HF”

6/19/2019 What is “HF” • HF – “High Frequency” An Introduction to HF • Details later, but for now, if you aren’t familiar with the term, call it “shortwave Communications radio” Gordon Good, KM6I 12 It Was A Dark And Stormy Night About Me • My introduction to HF • Licensed since 1975 (age 13) • Arlington, Texas, 1968 or so • Previously WN8YVI, WB8YVI, KC8ES • (yes, it really was dark and stormy) • Active on HF 1975-1981, some contesting at University of Michigan ARC W8UM • Inactive on HF for many years • Became active in MTV CERT/ARES around 2001 • Got back into HF + contesting in 2008 34 1 6/19/2019 Unit 1: The Electromagnetic Outline Spectrum 1. The Electromagnetic Spectrum • What is the electromagnetic spectrum? 2. The HF Amateur Radio Bands • Who uses it? 3. Modes • History 4. HF Propagation Basics 5. HF Antennas 6. Operating Practices 7. Having Fun on HF 56 TV broadcasting Submarine Satellite Communications Public Safety Communications Shortwave Radar broadcasting ELF VLF LF MF HF VHF UHF SHF EHF MW WiFi AM Radio FM Radio From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electromagnetic_spectrum 78 2 6/19/2019 Early Radio Experiments • First observations of radio phenomena in late 18th century • Mid-1800s – scientific foundation laid (Orsted, Henry, Faraday, Maxwell) • Late 1800s – Marconi, Tesla conduct experiments • 1901 – first claimed transatlantic wireless transmission From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electromagnetic_spectrum 910 Commercial Use Modern Telecommunications • First use of wireless was ship-to-shore • Using new modulation techniques (ways of communications using morse code encoding signals over radio) • First experimental audio broadcasts in • Digital communications 1906, first commercial station 1919 • Very high bandwidths (e.g. -

TRAFFIC HANDLER Training, Procedures, Resources, and Forms for the Traffic Handler

TRAFFIC HANDLER Training, Procedures, Resources, and Forms for the Traffic Handler As modified and updated, with permission, by Lou Everett, Sr., WA5LOU, as of January 15, 2012 Copyright © 2005-2012 by Harold Melton, KV5R **This document may be freely copied but may NOT be sold nor used, in whole or part, within any for-profit publication.** Contents FOR THE BEGINNER.................................................................................................2 Introduction to Radiogram Traffic ......................................................................................................... 2 Lesson 1: In the Beginning........................................................................................................................ 2 Lesson 2: Preparation................................................................................................................................ 2 Lesson 3: Checking In, and Basic Net Procedures ..................................................................................... 3 Lesson 4: The ARRL Radiogram Form, Sections and Preamble ................................................................. 4 Lesson 5: The ARRL Radiogram Form, Address Section........................................................................... 5 Lesson 6: The ARRL Radiogram Form, Text and Signature....................................................................... 7 OPERATING AIDS.....................................................................................................9 ARRL Message Precedences -

International Radio Telegraph Convention of Berlin: 1906

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻧﺘﺎﺝ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ (PDF)ﻫﺬﻩ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﻧﻘﻼً ﻣﻦ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﻓﻲ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ. 此电子版(PDF 版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提 供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. INTERNATIONAL RADIO TELEGRAPH CONVENTION OF BERLIN: 1906 AND PROPOSITIONS FOR THE INTER NATIONAL RADIO TELEGRAPH CONFERENCE OF LONDON WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 PAGE LAISSEE EN BLANC INTENTIONNELLEMENT PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PART 1. CONVENTION. International Radio Telegraph Conyention concluded between Germany, the United States of America, Argentina, Austria, Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Denmark, Spain, Trance, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Monaco, Norway, the Netherlands, Persia, Portugal, Roumania, Russia, Sweden, Turkey, and Uruguay. The undersigned, plenipotentaries of the Governments of the countries enumerated above, having met in con ference at Berlin, have agreed on the following Conven tion, subject to ratification: • ARTICLE. -

ARRL Field Day 2021 Rules

ARRL Field Day 2021 Rules Temporary Rule Waivers for ARRL Field Day 2021: For Field Day 2021 only, Class D stations may contact all other Field Day stations, including other Class D stations, for points. Class D and Class E stations are limited to 150 Watts PEP. (See Field Day rule 4.6) 1. Eligibility: Field Day is open to all amateurs in the areas covered by the ARRL/RAC Field Organizations and countries within IARU Region 2. DX stations residing in other regions may be contacted for credit and may submit entries as check-logs. 2. Object: To work as many stations as possible on the 160, 80, 40, 20, 15 and 10 Meter HF bands, as well as all bands 50 MHz and above, and in doing so to learn to operate in abnormal situations in less than optimal conditions. A premium is placed on developing skills to meet the challenges of emergency preparedness as well as to acquaint the general public with the capabilities of Amateur Radio. 3. Date and Time Period: Field Day 2021 will be held June 26-27. Field Day is ALWAYS the fourth full weekend of June, beginning at 1800 UTC Saturday and ending at 2059 UTC Sunday. 3.1. Class A and B (see below) stations that do not begin setting up until 1800 UTC on Saturday may operate the entire 27-hour Field Day period. 3.2. Stations who begin setting up before 1800 UTC Saturday may work only 24 consecutive hours, commencing when on-the-air operations begin. 3.3. -

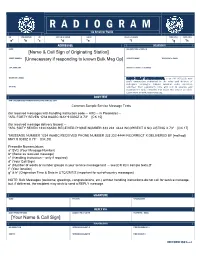

R a D I O G R

RADIOGRAM via Amateur Radio . NR PRECEDENCE HX STATION OF ORIGIN CHECK PLACE OF ORIGIN TIME (UTC) DATE (UTC) ADDRESSEE DELIVERED BY NAME DELIVERY TIME & METHOD STREET ADDRESS OPERATOR NAME TELEPHONE or EMAIL CITY, STATE, ZIP STATION LOCATION or ADDRESS TELEPHONE / EMAIL RADIO RELAY INTERNATIONAL is an IRS 501(c)(3) non- profit corporation dedicated to the relay and delivery of radiogram messages. Unpaid amateur radio operators OP NOTE: volunteer their equipment, time and skill to operate and maintain the radio networks that make this service possible. Learn more at www.radio-relay.org. BODY TEXT NON-CASE SENSITIVE COMMUNICATIONS; TYPE USING ALL CAPS SIGNATURE NAME POSITION ORGANIZATION REPLY VIA RADIO OPERATOR NAME ADDRESS OR LOCATION TELEPHONE / EMAIL TRACKING DATA RECEIVED FROM NETWORK DESIGNATOR TIME RECEIVED(UTC) SENT TO NETWORK DESIGNATOR TIME SENT(UTC) RRI FORM 1801 rev 1 Radiograms – Frequently Asked Questions What is a radiogram? A radiogram is a telegram sent by shortwave radio nets operating 365 days per year, 24-hours per day. These nets are sponsored by Radio Relay International and use a variety of communication technologies including voice, Morse code, and the latest, very sophisticated, digital methods. What is Radio Relay International? RRI is an IRS registered 501(c )(3) non-profit organization that sponsors a decentralized, survivable communication network over amateur radio, available for public service communications in time of disaster. While cellular networks and the Internet depend on the national electrical grid and fiber optic cable backbones, shortwave radio uses only the earth’s ionosphere making it independent of commercial infrastructure. Our operators are also widely dispersed, located all over the country and the world.