Ten Years of Gentleman Farming at Blennerhasset : with Co-Operative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allerdale Local Plan (Part 1)

Allerdale Borough Council Allerdale Local Plan (Part 1) Strategic and Development Management Policies July 2014 www.allerdale.gov.uk/localplan Foreword To meet the needs of Allerdale’s communities we need a plan that provides for new jobs to diversify and grow our economy and new homes for our existing and future population whilst balancing the need to protect the natural and built environment. This document, which covers the area outside the National Park, forms the first part of the Allerdale Local Plan and contains the Core Strategy and Development Management policies. It sets a clear vision, for the next 15 years, for how new development can address the challenges we face. The Core Strategy will guide other documents in the Allerdale Local Plan, in particular the site allocations which will form the second part of the plan. This document is the culmination of a great deal of public consultation over recent years, and extensive evidence gathering by the Council. The policies in the Plan will shape Allerdale in the future, helping to deliver sustainable economic development, jobs and much needed affordable housing for our communities. Councillor Mark Fryer Economic Growth Portfolio holder Contents What is the Allerdale Local Plan? ......................................................................... 1 What else is it delivering? ..................................................................................... 6 Spatial Portrait ..................................................................................................... -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Annual Report for the Year Ended the 31St March, 1963

Twelfth Annual Report for the year ended the 31st March, 1963 Item Type monograph Publisher Cumberland River Board Download date 01/10/2021 01:06:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26916 CUMBERLAND RIVER BOARD Twelfth Annual Report for the Year ended the 31st March, 1963 CUMBERLAND RIVER BOARD Twelfth Annual Report for the Year ended the 31st March, 1963 Chairman of the Board: Major EDWIN THOMPSON, O.B.E., F.L.A.S. Vice-Chairman: Major CHARLES SPENCER RICHARD GRAHAM RIVER BOARD HOUSE, LONDON ROAD, CARLISLE, CUMBERLAND. TELEPHONE CARLISLE 25151/2 NOTE The Cumberland River Board Area was defined by the Cumberland River Board Area Order, 1950, (S.I. 1950, No. 1881) made on 26th October, 1950. The Cumberland River Board was constituted by the Cumberland River Board Constitution Order, 1951, (S.I. 1951, No. 30). The appointed day on which the Board became responsible for the exercise of the functions under the River Boards Act, 1948, was 1st April, 1951. CONTENTS Page General — Membership Statutory and Standing Committees 4 Particulars of Staff 9 Information as to Water Resources 11 Land Drainage ... 13 Fisheries ... ... ... ........................................................ 21 Prevention of River Pollution 37 General Information 40 Information about Expenditure and Income ... 43 PART I GENERAL Chairman of the Board : Major EDWIN THOMPSON, O.B.E., F.L.A.S. Vice-Chairman : Major CHARLES SPENCER RICHARD GRAHAM. Members of the Board : (a) Appointed by the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and by the Minister of Housing and Local Government. Wilfrid Hubert Wace Roberts, Esq., J.P. Desoglin, West Hall, Brampton, Cumb. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

U2076 North Road, Aspatria 2013

Cumbria County Council THE COUNTY OF CUMBRIA (U2076 NORTH ROAD, ASPATRIA AND C2023 GILCRUX TO BEECH HILL) (TEMPORARY PROHIBITION OF THROUGH TRAFFIC) ORDER 2013 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that to enable Cumbria County Council to carry out carriageway resurfacing and drainage works, the County Council of Cumbria intends to make an Order the effect of which is to prohibit any vehicle from proceeding along the following lengths of road:- 1. U2076 North Road, Aspatria, from its junction with the A596 King Street extending in a north westerly direction for a distance of approximately 187 metres to its junction with the U7067 St Kentigans Way. A suitable alternaitive route for vehicles will be available via King Street, Outgang Road, St Mungos Park and North Road. 2. C2023 Gilcrux to Beech Hill, from a point approximately 260 metres north of its junction with the C2001 in Gilcrux, extending in a north westerly then north easterly direction for a distance of approximately 750 metres. A suitable alternative route for vehicles will be available as follows North Bound Vehicles - From the southern end of the closure continue along the C2023 to its junction with the C2001 in Gilcrux. Turn right and follow the C2001 to its junction with the C2003. Turn right and follow the C2003 to its junction with the A595 in Crosby Villa. Turn right and follow the A595 to its junction with the C2023 in Prospect. Turn right and follow the C2023 to the opposite end of the closure. South Bound Vehicles - Travel in the reverse direction of the above. A way for pedestrians and dismounted cyclists will be maintained at all times and The Order will come into operation on 19 August 2013 and may continue in force for a period of up to eighteen months from that date as and when the appropriate traffic signs are displayed, although it is anticipated that it will only be required as follows:- U2076 North Road, Aspatria closure – From 19 August 2013 for approximately 2 weeks; and C2023 Gilcrux to Beech Hill closure – From 2 September 2013 for approximately 2 weeks. -

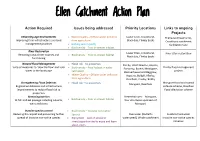

Ellen Catchment Action Plan

Ellen Catchment Action Plan Action Required Issues being addressed Priority Locations Links to ongoing Projects Enhancing Agri-Environments • Water Quality – Diffuse water pollution Lower Ellen, Crookhurst, Ellenwise (Crookhurst), Improving farm infrastructure and land from agriculture Black dub, Flimby becks Crookhurst catchment management practices • Bathing water quality facilitation fund • Biodiversity – Poor in-stream habitat River Restoration Lower Ellen, Crookhurst, River Ellen restoration Restoring natural river courses and • Biodiversity – Poor in-stream habitat Black dub, Flimby becks functioning Natural Flood Management • Flood risk – to properties Flimby, West Newton, Hayton, Suite of measures to ‘slow the flow’ and hold Flimby flood management • Biodiversity – Poor habitat in wider Parsonby, Bothel, Mealsgate, water in the landscape project catchment Blennerhasset and Baggrow, • Water Quality – Diffuse water pollution Aspatria, Bullgill, Allerby, from agriculture Dearham, Crosby, Birkby Strengthening Flood Defences • Flood risk – to properties Maryport flood and coastal Maryport, Dearham Engineered defences and infrastructure defence scheme, Dearham improvements to reduce flood risk to flood alleviation scheme properties Removing barriers Netherhall weir – Maryport, to fish and eel passage including culverts, • Biodiversity – Poor in-stream habitat four structures upstream of weirs and dams Maryport Invasive species control • Biodiversity – Invasive non-native Reducing the impact and preventing further species Overwater (Nuttall’s -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

A1 Tractor Parts & Quad Centre Adam Jackson Countryside Services

A1 Tractor Parts & Quad Centre Adam Jackson Countryside Services & Equipment, Briar Croft Cottage, Waberthwaite, Millom Agri Lloyd, Docklands, Dock Road, Lytham FY8 5AQ Amelia Watton,18 Waterloo Terrace, Arlecdon CA26 3UD Amy Donohue, Gatra Farm, Lamplugh CA14 4SA Aspatria Farmers, Station Works, Aspatria, Wigton Armstrong Watson,15 Victoria Place, Carlisle CA1 1EW Arnold Clark c/o 134 Nithersdale Drive, Glasgow Blood Bikes Cumbria, Bradley Bungalow, Ousby, penrith CA10 1QA Bavarian Caterers, 14 Cowan Brae, East Park Road, Blackburn BB1 8BB Beyond Brave Vintage, The Lonsdale Inn, 1-2 Lonsdale Terrace, Crosby Villa, Maryport CA15 6TG Bob Holroyd, 1 Laith Walk, Leeds LS16 6LA Border Cars, Lillyhall Ltd, Joseph Noble Road, Lillyhall Industrial Estate, Workington CA14 4JM Border Hydro Ltd, Miles Postlewaite, Armaside Farm, Lorton, Cockermouth CA13 9TL Brigham Holiday Park, Low Road, Brigham, Cockermouth CA13 0XH Cake District, Blackburn House, Hayton, Wigton CA7 2PD Carrs Agriculture, Montgomery Way, Rosehill Estate, Carlisle CA1 2UY Chris the Sweep, Chris Joyce, Croft House, Westnewton, Wigton CA7 3NX Citizens Advice Allerdale, The Town Hall, Oxford Street, Workington CA14 2RS Cockermouth First Responders, 20 Low Road Close, Cockermouth CA13 0GU Cockermouth Mountain Rescue, PO Box73, Cockermouth CA13 3AE County Fare, Dale Foot Farm, Mallerstang, Kirby Stephen, Cumbria Craig Robson, 7 Barmoore Terrace, Ryton NE40 3BB CT Hayton Ltd, Sandylands Road, Kendal, Cumbria LA9 6EX Cumbrai Constabulary, Cockermouth Police Station, Europe Way, Cockermouth, -

Blindbothel Parish Council

BLENNERHASSET AND TORPENHOW PARISH COUNCIL Clerk: Mrs. J. Rae, 33 Scholars Green, Wigton, Cumbria, CA7 9QW Tel: 016973 42138 Email: [email protected] 6th November 2019 Dear Councillor, You are summoned to attend the Meeting of the Parish Council on Wednesday 13th November, 2019 in Blennerhasset & Baggrow Social Centre commencing at 7.15 p.m. The business to be transacted is set out below. I trust you will be able to attend. Yours faithfully, Parish Clerk Simon Sharp, Planning and Building Control Manager from Allerdale Borough Council will provide Members with an update on the Blennerhasset Conservation Area appraisal at 7.15pm A G E N D A 1. To receive apologies for absence. 2. To authorise the Chairman to sign the minutes of the Meeting held on 4th September, 2019. 3. To receive declarations by elected and co-opted members of interests in respect of items on this agenda. 4. The Clerk to report on any requests received since the previous meeting for dispensations to speak and/or vote on any matter where a member has a disclosable pecuniary interest. 5. Public Voice Slot – Any elector within the Parish may put a question to the meeting in relation to matters affecting the Parish. At the discretion of the Chairman any other person present may put a question to the meeting in relation to matters on the agenda. A maximum of 30 minutes will be allowed for public comments and questions. 6. Reports from Outside Bodies: (a) Allerdale Borough Councillor (b) Cumbria County Councillor (c) Police Community Support Officer 7. -

North West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 PART B – Sub Areas in the North West River Basin District

North West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 PART B – Sub Areas in the North West river basin district March 2016 1 of 139 Published by: Environment Agency Further copies of this report are available Horizon house, Deanery Road, from our publications catalogue: Bristol BS1 5AH www.gov.uk/government/publications Email: [email protected] or our National Customer Contact Centre: www.gov.uk/environment-agency T: 03708 506506 Email: [email protected]. © Environment Agency 2016 All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. 2 of 139 Contents Glossary and abbreviations ......................................................................................................... 5 The layout of this document ........................................................................................................ 8 1 Sub-areas in the North West River Basin District ......................................................... 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 10 Management Catchments ...................................................................................................... 11 Flood Risk Areas ................................................................................................................... 11 2 Conclusions and measures to manage risk for the Flood Risk Areas in the North West River Basin District ............................................................................................... -

Allerdale Borough Council Rural Settlement List

ALLERDALE BOROUGH COUNCIL RURAL SETTLEMENT LIST In accordance with Schedule 1 of the Local Government and Rating Act 1997 the following shall be the Rural Settlement List for the Borough of Allerdale. Rural Area Rural Settlement Above Derwent Braithwaite Thornthwaite Portinscale Newlands Stair Aikton Aikton Thornby Wiggonby Allerby & Oughterside Allerby Prospect Oughterside Allhallows Baggrow Fletchertown Allonby Allonby Aspatria Aspatria Bassenthwaite Bassenthwaite Bewaldeth & Snittlegarth Bewaldeth Snittlegarth Blennerhasset & Torpenhow Blennerhasset Torpenhow Blindbothel Blindbothel Mosser Blindcrake Blindcrake Redmain Boltons Boltongate Mealsgate Bolton Low Houses Borrowdale Borrowdale Grange Rosthwaite Bothel & Threapland Bothel Threapland Bowness Anthorn Bowness on Solway Port Carlisle Drumburgh Glasson Bridekirk Bridekirk Dovenby Tallentire Brigham Brigham Broughton Cross Bromfield Blencogo Bromfield Langrigg Broughton Great Broughton Little Broughton Broughton Moor Broughton Moor Buttermere Buttermere Caldbeck Caldbeck Hesket Newmarket Camerton Camerton Crosscanonby Crosscanonby Crosby Birkby Dean Dean Eaglesfield Branthwaite Pardshaw Deanscales Ullock Dearham Dearham Dundraw Dundraw Embleton Embleton Gilcrux Gilcrux Bullgill Great Clifton Great Clifton Greysouthen Greysouthen Hayton & Mealo Hayton Holme Abbey Abbeytown Holme East Waver Newton Arlosh Holme Low Causewayhead Calvo Seaville Holme St Cuthbert Mawbray Newtown Ireby & Uldale Ireby Uldale Aughertree Kirkbampton Kirkbampton Littlebampton Kirkbride Kirkbride Little Clifton