Large Print California Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

1 Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain

Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain, Co-Ordinator TrailSafe Nevada 1285 Baring Blvd. Sparks, NV 89434 [email protected] Nev. Dept. of Cons. & Natural Resources | NV.gov | Governor Brian Sandoval | Nev. Maps NEVADA STATE PARKS http://parks.nv.gov/parks/parks-by-name/ Beaver Dam State Park Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park Big Bend of the Colorado State Recreation Area Cathedral Gorge State Park Cave Lake State Park Dayton State Park Echo Canyon State Park Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Site Fort Churchill State Historic Park Kershaw-Ryan State Park Lahontan State Recreation Area Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park Sand Harbor Spooner Backcountry Cave Rock Mormon Station State Historic Park Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park Rye Patch State Recreation Area South Fork State Recreation Area Spring Mountain Ranch State Park Spring Valley State Park Valley of Fire State Park Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park Washoe Lake State Park Wild Horse State Recreation Area A SOURCE OF INFORMATION http://www.nvtrailmaps.com/ Great Basin Institute 16750 Mt. Rose Hwy. Reno, NV 89511 Phone: 775.674.5475 Fax: 775.674.5499 NEVADA TRAILS Top Searched Trails: Jumbo Grade Logandale Trails Hunter Lake Trail Whites Canyon route Prison Hill 1 TOURISM AND TRAVEL GUIDES – ALL ONLINE http://travelnevada.com/travel-guides/ For instance: Rides, Scenic Byways, Indian Territory, skiing, museums, Highway 50, Silver Trails, Lake Tahoe, Carson Valley, Eastern Nevada, Southern Nevada, Southeast95 Adventure, I 80 and I50 NEVADA SCENIC BYWAYS Lake -

Oregon and Manifest Destiny Americans Began to Settle All Over the Oregon Country in the 1830S

NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ Manifest Destiny Lesson 1 The Oregon Country ESSENTIAL QUESTION Terms to Know joint occupation people from two countries living How does geography influence the way in the same region people live? mountain man person who lived in the Rocky Mountains and made his living by trapping animals GUIDING QUESTIONS for their fur 1. Why did Americans want to control the emigrants people who leave their country Oregon Country? prairie schooner cloth-covered wagon that was 2. What is Manifest Destiny? used by pioneers to travel West in the mid-1800s Manifest Destiny the idea that the United States was meant to spread freedom from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean Where in the world? 54°40'N Alaska Claimed by U.S. and Mexico (Russia) Oregon Trail BRITISH OREGON 49°N TERRITORY Bo undary (1846) COUNTRY N E W S UNITED STATES MEXICO PACIFIC OCEAN ATLANTIC OCEAN When did it happen? DOPA (Discovering our Past - American History) RESG Chapter1815 13 1825 1835 1845 1855 Map Title: Oregon Country, 1846 File Name: C12-05A-NGS-877712_A.ai Map Size: 39p6 x 26p0 Date/Proof: March 22, 2011 - 3rd Proof 2016 Font Conversions: February 26, 2015 1819 Adams- 1846 U.S. and Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission is granted to reproduce for classroom use. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission 1824 Russia 1836 Whitmans Onís Treaty gives up claim to arrive in Oregon Britain agree to Oregon 49˚N as border 1840s Americans of Oregon begin the “great migration” to Oregon 165 NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ Manifest Destiny Lesson 1 The Oregon Country, Continued Rivalry in the Northwest The Oregon Country covered much more land than today’s state Mark of Oregon. -

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-Creation of the Tribal Identity On

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican Contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 By Kumiko Noguchi B.A. (University of the Sacred Heart) 2000 M.A. (Rikkyo University) 2003 Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Native American Studies in the Office of Graduate Studies of the University of California Davis Approved Steven J. Crum Edward Valandra Jack D. Forbes Committee in Charge 2009 i UMI Number: 3385709 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3385709 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Kumiko Noguchi September, 2009 Native American Studies From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 Abstract The main purpose of this study is to show the path of tribal development on the Tule River Reservation from 1776 to 1936. It ends with the year of 1936 when the Tule River Reservation reorganized its tribal government pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. -

History Bits and Westward Quotes

History Bits & Westward Quotes on the Oregon Trail This page contains a variety of stories, statistics, and quotes about people, places and events on the Oregon Trail and early-day Northwest. During eight decades in the 1800s the Oregon Trail served as a natural corridor as the United States grew from the eastern half of the continent toward the west coast. The Oregon Trail ran approximately 2,000 miles west from Missouri toward the Rocky Mountains and ended in Oregon's Willamette Valley. The California Trail branched off in southern Idaho and brought miners to the gold fields of Sierra Nevada. The Mormon Trail paralleled much of the Oregon Trail, connecting Council Bluffs to Salt Lake City. Financing the Trip In the mid-1840s, settlers who traveled the Oregon Trail spent roughly $800 to $1200 to be properly outfitted. (Although there are many factors to consider, the cost of supplies would equate to roughly $32,000 in 2014 dollars). Many of the pioneers raised their capital by selling their farms and possessions. Along the way they found inflated prices for scarce commodities at trading posts and ferries. Once arriving in Oregon, there were scarce supplies available for purchase, requiring more ability to work in exchange for goods and services, than cash for purchasing. "Our miserable teams had nothing but water for dinner and we had crackers and milk. At this ranch, beef, potatoes, and squashes were for sale at the following outrageous prices... beef, 25 cents per lb., potatoes, 50 cents per lb., squashes, 2 dollars each and small at that.. -

1178937103.Pdf

i In 1832 the American National Caravan went under the title Na- tional Menagerie and sometimes Grand National Menagerie. It was still June. Titus & Angetine's show and carried the elephants Romeo and Juliet in addition to the rhinoceros. The four animal species that have intrigued menazerie historians The New and Rare Collection of Living Animals (Raymond & 1 ; are the elephant, the hippopotamus, the rhinoceros and the giraffe. Ogdcn) had no elephant until December, 1832 when Ilyder Ali was l The elephant has intrigued everyone, owners, performers, customers, imported and joined them in Charleston. ! the lot. Something about these huge, usually docile animals fas- Each of these shoa-s had a keeper who entered the lion's den in cinates human beings. "Seeing the elephant" is still an event, as the 1833 season. The National Slenagerie had a Mister Roberts from witness circus crowds or zoo-goers of today. The other three beasts. London. Raymond & Ogden (not using that title) had a Mister Gray. i being wild animals, somewhat rare and demanding of more care it is our impression that 1mcVan Amburgh was Roberts* cage boy. than elephants, while spectacular in the early days, do not have the Both rhinos were present as were the elephants. empathy elephants have. Elephants, to the historian, are not a Eighteen thirty-four uw June, Titus & Angevine and Raymond difficult problem in terms of tracing them, because of the habit of & Ogden use the proprietor's name as titles. From this year fonvard giving them names. The others, however, were never so acceptable this was the practice, and researchers are grateful for it. -

A Free Emigrant Road 1853: Elijah Elliott's Wagons

Meek’s Cutoff: 1845 Things were taking much longer than expected, and their Macy, Diamond and J. Clark were wounded by musket supplies were running low. balls and four horses were killed by arrows. The Viewers In 1845 Stephen Hall Meek was chosen as Pilot of the 1845 lost their notes, provisions and their geological specimens. By the time the Train reached the north shores of Harney emigration. Meek was a fur trapper who had traveled all As a result, they did not see Meek’s road from present-day Lake, some of the men decided they wanted to drive due over the West, in particular Oregon and California. But Vale into the basin, but rode directly north to find the west, and find a pass where they could cross the Cascade after a few weeks the independently-minded ‘45ers decided Oregon Trail along Burnt River. Mountains. Meek was no longer in control. When they no Pilot was necessary – they had, after all, ruts to follow - Presented by Luper Cemetery Inc. arrived at Silver River, Meek advised them to turn north, so it was not long before everyone was doing their own Daniel Owen and follow the creek to Crooked River, but they ignored his thing. Great-Grandson of Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Owen advice. So the Train headed west until they became bogged down at the “Lost Hollow,” on the north side of Wagontire Mountain. Here they became stranded, because no water could be found ahead, in spite of the many scouts searching. Meek was not familiar with this part of Oregon, although he knew it was a very dry region. -

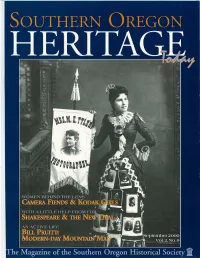

Link to Magazine Issue

----.. \\U\.1, fTI!J. Shakespeare and the New Deal by Joe Peterson ver wonder what towns all over Band, William Jennings America would have missed if it Bryan, and Billy Sunday Ehadn't been for the "make work'' was soon reduced to a projects of the New Deal? Everything from walled shell. art and research to highways, dams, parks, While some town and nature trails were a product of the boosters saw the The caved-in roofof the Chautauqua building led to the massive government effort during the decapitated building as a domes' removal, andprompted Angus Bowmer to see 1930s to get Americans back to work. In promising site for a sports possibilities in the resulting space for an Elizabethan stage. Southern Oregon, add to the list the stadium, college professor Oregon Shakespeare Festival, which got its Angus Bowmer and start sixty-five years ago this past July. friends had a different vision. They "giveth and taketh away," for Shakespeare While the festival's history is well known, noticed a peculiar similarity to England's play revenues ended up covering the Globe Theatre, and quickly latched on to boxing-match losses! the idea of doing Shakespeare's plays inside A week later the Ashland Daily Tidings the now roofless Chautauqua walls. reported the results: "The Shakespearean An Elizabethan stage would be needed Festival earned $271, more than any other for the proposed "First Annual local attraction, the fights only netting Shakespearean Festival," and once again $194.40 and costing $206.81."4 unemployed Ashland men would be put to By the time of the second annual work by a New Deal program, this time Shakespeare Festival, Bowmer had cut it building the stage for the city under the loose from the city's Fourth ofJuly auspices of the WPA.2 Ten men originally celebration. -

Elko County Nevada Water Resource Management Plan 2017

Elko County Nevada Water Resource Management Plan 2017 Echo Lake - Ruby Mountains Elko County Board of Commissioners Elko County Natural Resource Management Advisory Commission December 6, 2017 Executive Summary The Elko County Water Resource Management Plan has been prepared to guide the development, management and use of water resources in conjunction with land use management over the next twenty-five (25) years. Use by decision makers of information contained within this plan will help to ensure that the environment of the County is sustained while at the same time enabling the expansion and diversification of the local economy. Implementation of the Elko County Water Resource Management Plan will assist in maintaining the quality of life enjoyed by residents and visitors of Elko County now and in the future. Achievement of goals outlined in the plan will result in water resources found within Elko County being utilized in a manner beneficial to the residents of Elko County and the State of Nevada. The State of Nevada Water Plan represents that Elko County will endure a loss of population and agricultural lands over the next twenty-five years. Land use and development patterns prepared by Elko County do not agree with this estimated substantial loss of population and agricultural lands. The trends show that agricultural uses in Elko County are stable with minimal notable losses each year. Development patterns represent that private lands that are not currently utilized for agricultural are being developed in cooperation and conjunction with agricultural uses. In 2007, Elko County was the largest water user in the State of Nevada. -

Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Species Management Plan for the Upper Humboldt River Drainage Basin

STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE LAHONTAN CUTTHROAT TROUT SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE UPPER HUMBOLDT RIVER DRAINAGE BASIN Prepared by John Elliott SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN December 2004 LAHONTAN CUTTHROAT TROUT SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE UPPER HUMBOLDT RIVER DRAINAGE BASIN SUBMITTED BY: _______________________________________ __________ John Elliott, Supervising Fisheries Biologist Date Nevada Department of Wildlife, Eastern Region APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ __________ Richard L. Haskins II, Fisheries Bureau Chief Date Nevada Department of Wildlife _______________________________________ __________ Kenneth E. Mayer, Director Date Nevada Department of Wildlife REVIEWED BY: _______________________________________ __________ Robert Williams, Field Supervisor Date Nevada Fish and Wildlife Office U.S.D.I. Fish and Wildlife Service _______________________________________ __________ Ron Wenker, State Director Date U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management _______________________________________ __________ Edward C. Monnig, Forest Supervisor Date Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest U.S.D.A. Forest Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………………………………………………..1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….…2 AGENCY RESPONSIBILITIES……………………………………………………………….…4 CURRENT STATUS……………………………………………………………………………..6 RECOVERY OBJECTIVES……………………………………………………………………19 RECOVERY ACTIONS…………………………………………………………………………21 RECOVERY ACTION PRIORITIES BY SUBBASIN………………………………………….33 IMPLEMENTATION SCHEDULE……………………………………………………………..47 -

Hydrographic Basins Information

A p p e n d i x A - B a s i n 54 Crescent Valley Page 1 of 6 Basin 54 - Crescent Valley Crescent Valley is a semi-closed basin that is bounded on the west by the Shoshone Range, on the east by the Cortez Mountains, on the south by the Toiyabe Range, and on the north by the Dry Hills. The drainage basin is about 45 miles long, 20 miles wide, and includes an area of approximately 750 square miles. Water enters the basin primarily as precipitation and is discharged primarily through evaporation and transpiration. Relatively small quantities of water enter the basin as surface flow and ground water underflow from the adjacent Carico Lake Valley at Rocky Pass, where Cooks Creek enters the southwestern end of Crescent Valley. Ground water generally flows northeasterly along the axis of the basin. The natural flow of ground water from Crescent Valley discharges into the Humboldt River between Rose Ranch and Beowawe. It is estimated that the average annual net discharge rate is approximately 700 to 750 acre-feet annually. Many of the streams which drain snowmelt of rainfall from the mountains surrounding Crescent Valley do not reach the dry lake beds on the Valley floor: instead, they branch into smaller channels that eventually run dry. Runoff from Crescent Valley does not reach Humboldt River with the exception of Coyote Creek, an intermittent stream that flows north from the Malpais to the Humboldt River and several small ephemeral streams that flow north from the Dry Hills. Surface flow in the Carico Lake Valley coalesces into Cooks Creek, which enters Crescent Valley through Rocky Pass. -

Have Gun, Will Travel: the Myth of the Frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall

Feature Have gun, will travel: The myth of the frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall Newspaper editor (bit player): ‘This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, we print the legend’. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (dir. John Ford, 1962). Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott): ‘You know what’s on the back of a poor man when he dies? The clothes of pride. And they are not a bit warmer to him dead than they were when he was alive. Is that all you want, Steve?’ Steve Judd (Joel McCrea): ‘All I want is to enter my house justified’. Ride the High Country [a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon] (dir. Sam Peckinpah, 1962)> J. W. Grant (Ralph Bellamy): ‘You bastard!’ Henry ‘Rico’ Fardan (Lee Marvin): ‘Yes, sir. In my case an accident of birth. But you, you’re a self-made man.’ The Professionals (dir. Richard Brooks, 1966).1 he Western movies that from Taround 1910 until the 1960s made up at least a fifth of all the American film titles on general release signified Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, John Wayne and Strother Martin on the set of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance escapist entertainment for British directed and produced by John Ford. audiences: an alluring vision of vast © Sunset Boulevard/Corbis open spaces, of cowboys on horseback outlined against an imposing landscape. For Americans themselves, the Western a schoolboy in the 1950s, the Western believed that the western frontier was signified their own turbulent frontier has an undeniable appeal, allowing the closing or had already closed – as the history west of the Mississippi in the cinemagoer to interrogate, from youth U.