TOCC0496DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

A C AHAH C (Key of a Major, German Designation) a Ballynure Ballad C a Ballynure Ballad C (A) Bal-Lih-N'yôôr BAL-Ludd a Capp

A C AHAH C (key of A major, German designation) A ballynure ballad C A Ballynure Ballad C (A) bal-lih-n’YÔÔR BAL-ludd A cappella C {ah kahp-PELL-luh} ah kahp-PAYL-lah A casa a casa amici C A casa, a casa, amici C ah KAH-zah, ah KAH-zah, ah-MEE-chee C (excerpt from the opera Cavalleria rusticana [kah-vahl-lay-REE-ah roo-stee-KAH-nah] — Rustic Chivalry; music by Pietro Mascagni [peeAY-tro mah-SKAH-n’yee]; libretto by Guido Menasci [gooEE-doh may-NAH-shee] and Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti [jo-VAHN-nee tar-JO- nee-toht-TSAYT-tee] after Giovanni Verga [jo-VAHN-nee VAYR-gah]) A casinha pequeninaC ah kah-ZEE-n’yuh peh-keh-NEE-nuh C (A Tiny House) C (song by Francisco Ernani Braga [frah6-SEESS-kôô ehr-NAH-nee BRAH-guh]) A chantar mer C A chantar m’er C ah shah6-tar mehr C (12th-century composition by Beatriz de Dia [bay-ah-treess duh dee-ah]) A chloris C A Chloris C ah klaw-reess C (To Chloris) C (poem by Théophile de Viau [tay- aw-feel duh veeo] set to music by Reynaldo Hahn [ray-NAHL-doh HAHN]) A deux danseuses C ah dö dah6-söz C (poem by Voltaire [vawl-tehr] set to music by Jacques Chailley [zhack shahee-yee]) A dur C A Dur C AHAH DOOR C (key of A major, German designation) A finisca e per sempre C ah fee-NEE-skah ay payr SAYM-pray C (excerpt from the opera Orfeo ed Euridice [ohr-FAY-o ayd ayoo-ree-DEE-chay]; music by Christoph Willibald von Gluck [KRIH-stawf VILL-lee-bahlt fawn GLÔÔK] and libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi [rah- neeAY-ree day kahl-tsah-BEE-jee]) A globo veteri C AH GLO-bo vay-TAY-ree C (When from primeval mass) C (excerpt from -

Roger Quilter

ROGER QUILTER 1877-1953 HIS LIFE, TIMES AND MUSIC by VALERIE GAIL LANGFIELD A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham February 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Roger Quilter is best known for his elegant and refined songs, which are rooted in late Victorian parlour-song, and are staples of the English artsong repertoire. This thesis has two aims: to explore his output beyond the canon of about twenty-five songs which overshadows the rest of his work; and to counter an often disparaging view of his music, arising from his refusal to work in large-scale forms, the polished assurance of his work, and his education other than in an English musical establishment. These aims are achieved by presenting biographical material, which places him in his social and musical context as a wealthy, upper-class, Edwardian gentleman composer, followed by an examination of his music. Various aspects of his solo and partsong œuvre are considered; his incidental music for the play Where the Rainbow Ends and its contribution to the play’s West End success are examined fully; a chapter on his light opera sheds light on his collaborative working practices, and traces the development of the several versions of the work; and his piano, instrumental and orchestral works are discussed within their function as light music. -

Canberra International Music Festival 27 April – 6 May 2018

CANBERRA INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL 27 APRIL – 6 MAY 2018 Experience the music adventure CONCERT CALENDAR PAGE 1 OPENING GALA 7.30 pm Friday April 27 Fitters’ Workshop 5 Personal Injury Lawyers 2 DAPPER'S DELIGHT 11 am Saturday April 28 Fitters’ Workshop 9 3 ROGER WOODWARD I 3 pm Saturday April 28 Fitters’ Workshop 11 4 FOUR SEASONS 8 pm Saturday April 28 Fitters’ Workshop 15 5 BACH ON SUNDAY 11 am Sunday April 29 Fitters’ Workshop 19 National Gallery of Australia 6 ENOCH ARDEN 3 pm Sunday April 29 23 Instrumental Fairfax Theatre 7 CLASSIC SOUVENIR 6.30 pm Sunday April 29 Fitters’ Workshop 27 Starts at 8 FROM THE LETTER TO THE LAW 11 am Monday April 30 31 in protecting the National Library of Australia 9 ISRAEL IN EGYPT 6.30 pm Monday April 30 Fitters’ Workshop 37 10 am, 10 REQUIEM Tuesday May 1 Australian War Memorial 41 11.30 am rights of more 11 ROGER WOODWARD II 6.30 pm Tuesday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 45 12 GLASS GAMES 12 pm Wednesday May 2 Canberra Glassworks 49 Canberrans. 13 ULYSSES NOW 6.30 pm Wednesday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 52 8.30 am - –– TASTE OF THE COUNTRY Thursday May 3 Annual Festival Trip 57 4 pm 14 ORAVA QUARTET 6 pm Thursday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 59 THE ASPIRATIONS OF A J O 15 8 pm Thursday May 3 Canberra Theatre 63 M R DAISE MORROW At Maliganis Edwards Johnson, we’ve seen 2018 Canberra 16 RETURN TO BASICS 11 am Friday May 4 Canberra Grammar School 65 firsthand how an injury can impact lives. -

Australian Chamber Music with Piano

Australian Chamber Music with Piano Australian Chamber Music with Piano Larry Sitsky THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Sitsky, Larry, 1934- Title: Australian chamber music with piano / Larry Sitsky. ISBN: 9781921862403 (pbk.) 9781921862410 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Chamber music--Australia--History and criticism. Dewey Number: 785.700924 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Preface . ix Part 1: The First Generation 1 . Composers of Their Time: Early modernists and neo-classicists . 3 2 . Composers Looking Back: Late romantics and the nineteenth-century legacy . 21 3 . Phyllis Campbell (1891–1974) . 45 Fiona Fraser Part 2: The Second Generation 4 . Post–1945 Modernism Arrives in Australia . 55 5 . Retrospective Composers . 101 6 . Pluralism . 123 7 . Sitsky’s Chamber Music . 137 Edward Neeman Part 3: The Third Generation 8 . The Next Wave of Modernism . 161 9 . Maximalism . 183 10 . Pluralism . 187 Part 4: The Fourth Generation 11 . The Fourth Generation . 225 Concluding Remarks . 251 Appendix . 255 v Acknowledgments Many thanks are due to the following. -

The Piano Prelude in the Early Twentieth Century: Genre and Form

THE PIANO PRELUDE IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY: GENRE AND FORM by Siew Yuan Ong, B.Mus.(Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Master of Arts of The University of Western Australia School of Music Faculty of Arts 2005 Abstract This thesis focuses on a group of keyboard pieces composed in the first half of the twentieth century entitled ‘prelude’, and explores the issue of genre, investigating the significance in the application of this generic title, and the development of the piano prelude in this period. The application of a generic title often invokes the expectation of its generic features – its conventional and formal characteristics. Though the prelude is one of the oldest genres in the history of keyboard music, it has relatively few conventions, and hence, with the abandonment of its primary function – the prefatory role – in the nineteenth century, it has been considered an indeterminate genre. Rachmaninoff, however, asserted that a generic title should carry with it appropriate generic manifestations, which parallelled similar generic concepts in literature. This expectation of generic traits is like setting up a ‘generic contract’, offering an invitation to either conform or reform, and thus affecting its course of development. A survey of the prelude’s historical development points to six rather consistent generic conventional and formal characteristics: (i) tonality, (ii) pianistic/technical figuration, (iii) thematic treatment and formal structure, (iv) improvisatory style, (v) mood content, and (vi) brevity. Though these general characteristics may overlap with other genres, it is their collective characteristics that have contributed to the genre’s unique identity. -

A.E. Floyd and the Promotion of Australian Music Ian Burk

2009 © Ian Burk, Context 33 (2008): 81–95. A.E. Floyd and the Promotion of Australian Music Ian Burk Alfred Ernest Floyd, who lived from 1877 to 1974, loomed large on the musical landscape of Australia for more than fifty years, enjoying what today would be described as iconic status. Floyd arrived in Australia from the United Kingdom in February 1915 to take up an appointment as Organist and Master of the Choristers at St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne, where he maintained and sustained the role of organist with considerable skill and public acclaim for more than thirty years. Floyd was also successful in raising the profile of early music in Melbourne for over two decades, his primary interest being English choral music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. At the same time he extended his reach into music criticism, broadcasting, music education and publishing. Floyd devoted his professional life to the performance and promulgation of music. The focus of his promotion of music for all was education in the widest sense. This he undertook through the various media (press, radio and television) and through public lectures and music appreciation classes. As music critic for the Argus, a regular columnist for the Radio Times, and as a broadcaster for the ABC,1 and commercial stations in Melbourne, Floyd established a significant following as a commentator and entertainer and he was influential in shaping public taste in music and attitudes towards music. Floyd’s personal papers, now housed in the Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne,2 radio archives, newspapers, journals, and the reminiscences of those who worked with him professionally provided the material for this article. -

University of Cape Town August 2011 DECLARATION

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the Universityof of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR PIANO DUET: A SUPPLEMENT TO CAMERON MCGRAW'S PIANO DUET REPERTOIRE by LUIS MIGUEL DE ARAUJO MAGALHAES Town Cape of Student no. MGLLUIOOI University Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Music by Perfonnance and Thesis in the Department of Music in the Faculty of Humanities University of Cape Town August 2011 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Music at the University of Cape Town, has not been submitted by me previously for a degree at another university. Town Cape of University Luis Miguel de Araujo Magalhaes Cape Town, August 2011 \ ABSTRACT The keyboard duet is one of the most appreciated and widely available music genres, but literature devoted to the repertoire for piano duet is surprisingly scarce and often incomplete. The one pUblication that does justice to the genre is Cameron McGraw's Piano Duet Repertoire, and this study took as its point of departure the gathering of information on works for piano duet not listed in McGraw, with a view to compiling a supplement to that work. Each entry provides, apart from the title of the work and the composers name, dates and nationality, the following information (where applicable and/or available): composer's website, movements, approximate duration, the arranger's name, the original medium, publication details and/or other information on availability (locationTown of manuscript or on-line source). -

Newsletter24-Discography-1.Pdf

of the DELIUS SOC!ErY (President: Eric Fenby, OoB.E.) Hon. Secretary: Miss Estelle Palmley Hon. Treasurer: Miss Ann Todd Editor: John White No. 24 September, 1969. This Newsletter ls devoted to one purpose: the distribution of the Sooiety's first publication, the long awaited Delius disoography, which is circulated in complete form, and not in sections, as discussed at our last Annual General Meet+ng. I must apologise to the Membership, and especially to Mr. Stuarl UptOD and Mr. Malcolm 'Walker, the authors, for delaying the despatch of the booklets still fUrtherJ they were received in July but illness prevented me from taking any earlier action. I am sure all members will wish to join me in thanking Mr. UptOD and Mr. Walker for ·their devoted \r1Ork on this project, now brought to such a successful conclusion. Mr. Upton has breught my attention to· certain printing errore- and· -to one addition which should be noted in the text and these are given below. Delius DiSCOgraphy ERRATA Page 11 For "Painoforte" read "Pianoforte" Page 23 For IIHQS 1126/8)11 read "HQS 1126(S)" Page 37 For "Grief" read "Grieg" Page 38 For "P'Nelll" read "O'Neill" Page 39 Underline "Albert Sazmnons" Page 40 For IIRhide" read "Rhine" ADDITION !'YE Four Centuries of Harpsichord Music GSGC 14113(S) This record contains Denee for llarpsiehord (DELIUS) Peter Cooper - Harpsichord. FREDERICK DELIUS -, .• A DISCOGRAPHY STUART UPTON & MALCOLM WALKER THE RECORDED WORKS OF FREDERICK DELIUS (1862 - 1934) The following Index covers all commercial gramophone records issued to the Public over a period of almost fifty years. -

Uncovering the Unpublished Chamber Music of George Frederick Boyle Volume I: Dissertation

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2016 Uncovering the unpublished chamber music of George Frederick Boyle Volume I: Dissertation Ryan Davies Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Davies, R. (2016). Uncovering the unpublished chamber music of George Frederick Boyle Volume I: Dissertation. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1769 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1769 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Tocc0470booklet.Pdf

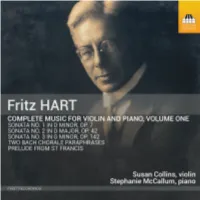

FRITZ HART: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, VOLUME ONE by Peter Tregear Born in Brockley, South London, Fritz Bennicke Hart (1874–1949) stands as one of the more extraordinary figures of the so-called English Musical Renaissance, all the more so because he remains so little known. His mother was a piano teacher from Cornwall and his father a travelling salesman of Irish ancestry born in East Anglia. The eldest of five, Hart was not encouraged to pursue a musical career as a child, but piano lessons from his mother were later complemented by the award of a choristership at Westminster Abbey, then under the direction of Frederick Bridge – ‘Westminster Bridge’, as he was inevitably nicknamed. A year earlier Bridge had been appointed professor of harmony and counterpoint at the newly constituted Royal College of Music and in 1893 Hart would join him there as a student of piano and organ. In addition, in the years between his tenure as a chorister and his enrolling at the RCM, Hart had been introduced to both the music and the aesthetic philosophy of Richard Wagner and had also become a regular and enthusiastic audience member of the Saturday orchestral concerts held at the Crystal Palace and the RCM. It seems Hart quickly became better known at the RCM for his ardent interest in opera and music drama than for his piano-playing. Indeed, Imogen Holst credits Hart with having introduced her father, Gustav, to Wagner.1 But unlike Holst and other contemporaries, such as Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, Samuel Coleridge- Taylor and William Hurlstone, Hart did not formally study composition. -

A Discography

Alan Hovhaness: A Discography AUG 2018 8 March 1911 - 21 June 2000: In Memoriam compiled by Eric Kunze 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Alphabetic Listing 3 2. Appendix A: Labels and Numbers 226 3. Appendix B: Chronology of Releases 233 4. Appendix C: Want List 235 5. Appendix D: By Opus Number 240 2 ALAN HOVHANESS: A DISCOGRAPHY (OCT 1996; revised AUG 2018) (Library of Congress Card No. 97-140285) Compiled by Eric Kunze, 8505 16th Ave NE, Seattle, WA 98115, USA, e-mail [email protected], phone 206-280-6374 with much-appreciated assistance from Mr. Alan and Mrs. Hinako Hovhaness ne Fujihara, Robert Jordan, Stephen Trowell, Marco Shirodkar, Martin Berkofsky, Glenn Freeman, Marvin Rosen, Nicola Giosmin, Stephen Ellis, Maris Kristapsons, Joel Salsman, Jim Robinson of Gramma's Attic, Larry Bright, David Canfield of Ars Antiqua, Leslie Gerber of Parnassus Records and Byron Hanson. Corrections and additions can be sent to Eric Kunze. He also seeks to fill in any question marks and add the * items, summarized in Appendix C, to his collection. New performances on commercial labels are denoted ►, on small labels and private issues ►. Gray entries are reissues. Of 434 listed opuses, about 208 have not been recorded, including all of his operas, 32 symphonies and numerous large choral works. By far the most recorded of Alan Hovhaness's works is his Prayer of St. Gregory, op. 62b, an excerpt from his opera Etchmiadzin, with 68 total releases (1 78, 15 LP, 53 CD). It has been recorded for trumpet and strings, trumpet and brass, trumpet and organ, double bass and organ, and trombone and piano.