Shaping the Future... the Development of Voluntary and Community Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote for Sedgefield in the People's Millions!

Published by Sedgefield Development Partnership: Company No: 4312745 Charity No: 1100906 Insert logo in Sedgefield News current month’s colour Produced by volunteers for the villagers of Sedgefield, Bradbury & Mordon November 2005 Vote for Sedgefield in the People’s Millions! Congratulations to Sedgefield The idea is to encourage us to management of the woodland areas Community Association! make more use of the gardens by and some sensitive lighting would They have made it through to providing a safer and more be designed to reduce the the last six in the Tyne Tees pleasant environment. Winning the opportunities for the kind of anti- region for a People’s Millions grant would allow access for elderly social behaviour which can and grant, with their bid to and disabled visitors to be greatly often does take place there. revitalise the grounds and lake improved, with better footpaths So tune in to North East Tonight behind Ceddesfeld Hall. and seating. Importantly, careful (Tyne Tees) on Wednesday 2nd November between 6 - 6:30pm, to vote for the Sedgefield project in the People’s Millions contest. The winner could be awarded up to £50,000 from the Big Lottery Fund! Sedgefield is up against the much larger Wansbeck District Council’s project and they have many more prospective voters, so we need every-one to take the time to vote online or by telephone. Ask all your friends to vote too, and don’t leave it too late - the winners will be announced the next day on North East Tonight. Rainbows skip for Air Ambulance 2nd Sedgefield Rainbows recently presented a £150 cheque to the Great North Air Ambulance’s area co-ordinator, Sue Cave. -

MAN/00EJ/RTB/2019/0011 Property : 4 Laburnum Road

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL PROPERTY CHAMBER (RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY) Case Reference : MAN/00EJ/RTB/2019/0011 Property : 4 Laburnum Road, West Cornforth, Ferryhill, County Durham DL17 9NJ Applicant : Colin Covey and Doreen Covey Respondent : Livin Housing Limited Type of Application : Determination of Right to Buy Housing Act 1985, Schedule 5, Paragraph 11, as amended by Housing Act 2004, Section 181 Tribunal Members : Mr I D Jefferson TD BA BSc FRICS Mrs K Usher Date of Determination : 11 October 2019 Date of Decision 18 October 2019 DECISION © CROWN COPYRIGHT 2019 1 Decision: The Tribunal is satisfied that the Property is particularly suitable for occupation by elderly persons and that the Respondent is able to rely upon Schedule 5 paragraph 11 of the Housing Act 1985. The Applicant is therefore denied the right to buy. Application and Background 1. The Applicant is the tenant and occupier of the Property and gave notice to the Landlord of intention to exercise the right to buy. The papers are not before the Tribunal but the Tribunal assume that the Application was received. 2. The Landlord then served a Notice (form RTB 2) dated 11 July 2019 on the Applicant under Section 124 of the Act denying the right to buy on the grounds set out in paragraph 11 to Schedule 5 of the Act. 3. By an application dated 26 July 2019 the Applicant applied to the Tribunal for a determination as to whether the dwelling house is suitable for occupation by elderly persons. 4. The Application was copied to the Landlord. Representations and hearing 5. The Tribunal received written representations from both parties. -

7206 Thf London Gazette, 11 September, 19J 4

7206 THF LONDON GAZETTE, 11 SEPTEMBER, 19J 4. SECOND SCHEDULE. ESSEX. Municipal Boroughs.—Chelmsford: Colches- PROHIBITED AREAS. ter : Harwich: Maldon: Southend-on-Sea. Urban Districts.—Brentwood: Brightlingeea:. The following areas are prohibited areas in Burnham-on-Crouch: Clacton: Frinton-on- England: — Sea: Grays Thurrock: Leigh-on-Sea: Shoe- CHESHIRE. bury ness : Tilbury: Walton-on-the-Naze. County Boroughs.—Birkenhead: Chester: Witham: Wivenhoe. Wallasey. Rural Districts.—Billericay: Braintree—(Civ: Urban Districts.—Bromborough : Ellesmere Parishes of—Feering, Great Coggeshall Port and Whitby: Higher Bebington: Kelvedon, Little C'oggeshall, MarkshalU Hoole: Hoylake and West Kirby: Lower Rivenhall, Fairsted, Faulkbourne, Hatfield. Bebington: Neston and Parkgate: Runcorn. Peverel, and Terling only) : Chelmsford: Rural Districts.—Chester (Civil Parishes of— Lexden: Maldon : Orsett: Rochf ord: Tend." Bache, Backford, Blacom-cum-Crabwall, ring. Bridge Trafford, Capenhurst, Caughall, GLOUCESTERSHIRE . Chorlton by Backford, Croughton, Dunham- County Borough.—Bristol. on-the-Hill, Elton, Great Saughall, Haps- Urban Districts.—C'oleford : Kingswood. ford, Hoole Village, Ince, Lea by Backford, Rural Districts.—Chipping Sodbury: Lyd- Little Saughall, Little Stanney, Mickle bury: Thornbury: Warmley: West Dean. Trafford, Mollington, Moston, Newton-by- Chester, Picto^i, Shotwick, Shotwick Park, HAMPSHIRE. Stoke, Thornton-le-Moors, Upton-by- County Boroughs.—Bournemouth: Ports- Chester, Wervin, Wimbolds Trafford, and mouth : Southampton. Woodbank only): Runcorn (Civil Parishes Municipal Boroughs.—Christchurch : Lyming- of—Acton Grange, Antrobus, Appleton, ton: Romsey. Bartington, Crowley, Daresbury, Dutton, Urban Districts.—Eastleigh and Bishopstoke . Grappenhall, Great Budworth, Hatton, Fareham: Gosport and Alverstoke. Higher Whitley, Keckwick, Latchford Havant: Itchen: Warblington. Without, Lower Whitley, Moore, Newton- Rural Districts.—Christchurch : Fareham by-Daresbury, Preston-on-the-Hill, Seven Havant: Ljonington: New Forest: Romsey. -

Local Government Review in the Derwentside District Council Area, County Durham

Local Government Review in the Derwentside District Council Area, County Durham Research Study Conducted for The Boundary Committee for England April 2004 Contents Introduction 3 Summary of Key Findings 5 Methodology 7 Definitions of Social Grade and Area 11 Topline Findings (Marked-up Questionnaire) 13 Introduction This summary report presents the key findings of research conducted by the MORI Social Research Institute on behalf of The Boundary Committee for England in the Derwentside District Council area, County Durham. The aim of the research was to establish residents’ views about alternative patterns of unitary local government. Background to the Research In May 2003, the Government announced that a referendum would take place in autumn 2004 in the North East, North West and Yorkshire and the Humber regions on whether there should be elected regional assemblies. The Government indicated that, where a regional assembly is set up, the current two-tier structure of local government - district, borough or city councils (called in this report ‘districts’) and county councils - should be replaced by a single tier of ‘unitary’ local authorities. In June 2003, the Government directed The Boundary Committee for England (‘the Committee’) to undertake an independent review of local government in two-tier areas in the three regions, with a view to recommending possible unitary structures to be put before affected local people in a referendum at a later date. MORI was commissioned by COI Communications, on behalf of the Committee, to help it gauge local opinion. The research was in two stages. First, in summer 2003, MORI researched local residents’ views about local government and how they identify with their local community. -

2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No. 2) Order 2004 Made - - - - 6th December 2004 Laid before Parliament 10th December 2004 Coming into force - - 31st December 2004 The First Secretary of State, having received a report from the Audit Commission(a) produced under section 99(1) of the Local Government Act 2003(b), in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 99(4) of that Act, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No.2) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 31st December 2004. (2) This Order applies in relation to English local authorities(c). Categorisation report 2. The English local authorities, to which the report of the Audit Commission dated 8th November 2004 relates, are, by this Order, categorised in accordance with their categorisation in that report. Excellent authorities 3. The local authorities listed in Schedule 1 to this Order are categorised as excellent. Good authorities 4. The local authorities listed in Schedule 2 to this Order are categorised as good. Fair authorities 5. The local authorities listed in Schedule 3 to this Order are categorised as fair. (a) For the definition of “the Audit Commission”, see section 99(7) of the Local Government Act 2003. (b) 2003 c.26. The report of the Audit Commission consists of a letter from the Chief Executive of the Audit Commission to the Minister for Local and Regional Government dated 8th November 2004 with the attached list of local authorities categorised by the Audit Commission as of that date. -

Local Government Review in the Sedgefield Borough Council Area, County Durham

Local Government Review in the Sedgefield Borough Council Area, County Durham Research Study Conducted for The Boundary Committee for England April 2004 Contents Introduction 3 Summary of Key Findings 5 Methodology 7 Definitions of Social Grade and Area 11 Topline Findings (Marked-up Questionnaire) 13 Introduction This summary report presents the key findings of research conducted by the MORI Social Research Institute on behalf of The Boundary Committee for England in the Sedgefield Borough Council area, County Durham. The aim of the research was to establish residents’ views about alternative patterns of unitary local government. Background to the Research In May 2003, the Government announced that a referendum would take place in autumn 2004 in the North East, North West and Yorkshire and the Humber regions on whether there should be elected regional assemblies. The Government indicated that, where a regional assembly is set up, the current two-tier structure of local government - district, borough or city councils (called in this report ‘districts’) and county councils - should be replaced by a single tier of ‘unitary’ local authorities. In June 2003, the Government directed The Boundary Committee for England (‘the Committee’) to undertake an independent review of local government in two-tier areas in the three regions, with a view to recommending possible unitary structures to be put before affected local people in a referendum at a later date. MORI was commissioned by COI Communications, on behalf of the Committee, to help it gauge local opinion. The research was in two stages. First, in summer 2003, MORI researched local residents’ views about local government and how they identify with their local community. -

Drjonespodiatryleaflet.Pdf

DARLINGTON NHS Foundation Trust Hundens Rehabilitation Centre Building A Hundens Willington Health Centre DERWENTSIDE EASINGTON Chapel Street, Willington DL15 0EQ Service Lane Darlington DL1 1JE Shotley Bridge Community Hospital Murton Clinic delivered by County Durham & Darlington NHS Service delivered by County Durham & Consett DH8 0NB 21 Woods Terrace, Murton SR7 9AG Foundation Trust. Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. Service delivered by County Durham & Service by NHS City Hospitals Sunderland Darlington NHS Foundation Trust CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care at CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care Peterlee Community Hospital O’Neill Drive, the clinics indicated above, they also provide at the clinics indicated above, they also Stanley Primary Care Centre Clifford Road, Peterlee SR8 5UQ Service by North Tees & following an initial assessment clinics at the provide following an initial assessment clinics Stanley DH9 0AB Service delivered by County Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust following venues:- at the following venues:- Durham & Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. Cockfield GP Surgery Peterlee Health Centre Gainford GP Surgery Flemming Place, Peterlee SR8 1AD Evenwood GP Surgery CDDFT provide assessment and ongoing care at Whinfield Medical Practice Whinbush Way, Service by Minor Ops Limited Middleton-in-Teasdale GP Surgery the clinics indicated above, they also provide Darlington DL1 3RT Service by Minor Ops Limited following an initial assessment clinics at the Seaham Primary Care Centre following venues:- DURHAM DALES -

THE RURAL ECONOMY of NORTH EAST of ENGLAND M Whitby Et Al

THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND M Whitby et al Centre for Rural Economy Research Report THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST ENGLAND Martin Whitby, Alan Townsend1 Matthew Gorton and David Parsisson With additional contributions by Mike Coombes2, David Charles2 and Paul Benneworth2 Edited by Philip Lowe December 1999 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham 2 Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scope of the Study 1 1.2 The Regional Context 3 1.3 The Shape of the Report 8 2. THE NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE REGION 2.1 Land 9 2.2 Water Resources 11 2.3 Environment and Heritage 11 3. THE RURAL WORKFORCE 3.1 Long Term Trends in Employment 13 3.2 Recent Employment Trends 15 3.3 The Pattern of Labour Supply 18 3.4 Aggregate Output per Head 23 4 SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DYNAMICS 4.1 Distribution of Employment by Gender and Employment Status 25 4.2 Differential Trends in the Remoter Areas and the Coalfield Districts 28 4.3 Commuting Patterns in the North East 29 5 BUSINESS PERFORMANCE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 5.1 Formation and Turnover of Firms 39 5.2 Inward investment 44 5.3 Business Development and Support 46 5.4 Developing infrastructure 49 5.5 Skills Gaps 53 6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 55 References Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The scope of the study This report is on the rural economy of the North East of England1. It seeks to establish the major trends in rural employment and the pattern of labour supply. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

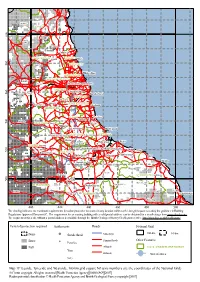

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. -

Sedgefield Relief in Need Charity

Sedgefield Relief in Need Charity We offer support and grants to individuals and organisations for their education, training and quality of life for people who live in the parishes of Bishop Middleham, Bradbury, Fishburn, Mordon, Sedgefield and Trimdon. Applications are usually made via health, social services professional or Citizens Advice - or for educational grants by an application form. Who to contact Contact name Anne Gladwin Contact Clerk to the Trustees position Telephone 01740 620811 E-mail [email protected] Notes Charity number: 230395 Where to go Address 46 Whitehouse Drive Sedgefield County Durham Postcode TS21 3BU Other details Cost Free description Referral and Sedgefield District Relief in Need Charity is availability for the help of residents in Bishop notes Middleham, Bradbury, Cornforth, Fishburn, Mordon, Sedgefield and Trimdon. Disclaimer Durham County Council's Families Information Service does not promote nor endorse the services advertised on this website. Anyone seeking to use/access such services does so at their own risk and may make all appropriate enquiries about fitness for purpose and suitability to meet their needs. Call the Families Information Service: 03000 269 995 or email: [email protected] Disclaimer: Durham County Council's Families Information Service encourages and promotes the use of plain English. We therefore reserve the right to amend any information supplied as necessary. Durham County Council's Families Information Service does not promote nor endorse the services advertised on this website. Anyone seeking to use/access such services does so at their own risk and may make all appropriate enquiries about fitness for purpose and suitability to meet their needs.. -

Neighbourhood Development Plan for Sedgefield, County Durham

Neighbourhood Development Plan for Sedgefield, County Durham Planning period 2018 to 2033 Adopted by Durham County Council 23 October 2019 Page 1 of 108 Contents . Foreword 4 Section 1 - Introduction and Land Use Policies 5 Introduction 6 Vision 9 The Objectives of ‘The Sedgefield Plan’ 9 Challenges and Principles for the Development and Growth of Sedgefield 13 Local Context 15 History of Sedgefield 17 The Sedgefield Plan Strategy 19 Strategic Review Every 5 Years 20 Monitoring of the Plan 20 Community Action, Green Spaces 21 Neighbourhood Plan Policies 22 Community Assets 36 Appendix 1: Sedgefield Designated Parish Boundary 37 Appendix 2: Built-up Area Boundary Map 38 Appendix 3: Conservation Area Boundary Maps 39 Section 2 – Basic Conditions Statement, SEA Screening and HRA Screening 40 Basic Conditions Statement – An Introduction 41 NPPF Obligations 43 The Local Development Plan Obligations 48 European Union Obligations 55 Conclusion 55 SEA Screening – An Introduction 56 Stage One: Establishing the Need for a Strategic Environmental Assessment 57 Page 2 of 108 Stage Two: Likely Significant Effects on the Environment 61 Conclusion 68 HRA Screening – An Introduction 69 Stage One: Likely Effects on Natura and Ramsar Sites 70 Conclusion 71 Appendix 1: Application of the SEA Directive to Plans and Programmes 72 Section 3 - Statement of Consultation and Community Engagement 73 Community Engagement 74 Community Survey 74 Young People’s Survey 77 Public Meetings 78 Consultation with Schools 80 Consultation with Landowners, Developers, Utilities and Institutions 81 The Neighbourhood Planning Process 84 Statement of Community Engagement and Statutory Consultation 87 Summary of Community Engagement 90 Summary of Statutory Consultation 94 Section 4 - Business Support Strategy 105 Sedgefield: A Place to do Business 106 Page 3 of 108 Foreword .