State of the Park Report: Valley Forge National Historical Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Valley Forge

Exploring Valley Forge Valley Forge received its name from the iron forge The recommended first stop is the park’s visitor These, plus replicated huts, memorials, monu- Other points of interest include trace remains at the visitor center. For a fee, the tour provides hibited on the bike/foot trails and all park roads. built along Valley Creek in the 1740s. By the time center. There an 18-minute film, shown every 30 ments, and markers, help to tell the story of the of historic roads, the site of Fatland Ford—the a more direct and informative way to travel to Mountain bikes are restricted to established and of the Revolution, a sawmill and gristmill had been minutes, provides an introduction to life during men who, at Valley Forge, helped to write an low-water-crossing point used by the British the most historically significant areas in the approved trails and park roads. Cross-country use added, making the place an im por tant supply base the encampment. Displays and artifacts in the im perishable chapter in the history of America’s army en route to capturing the patriot capital park. A cell phone tour is also available. Just look through fields and wooded areas is prohibited. for the Americans. The Brit ish destroyed the forge ex hibit area illustrate what life was like in the struggle for independence. of Phila del phia—and the site of Sullivan’s Bridge, for the cell phone tour icon at various places Please do not picnic or en gage in recreational and mills in 1777, and only ruins remained at the camp. -

Valley Forge, a Chronicle of American Heroism

Class £r "^ 3 4^ Bnnic ^' ^ M- Gop}TiglitN° COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2010 witii funding from Tine Library of Congress Iittp://www.arcliive.org/details/valleyforgechron04tayl National Memorial Arch in honor of George Washington Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army of the Revo- lution and his Officers, located upon the outer line Boulevard near the intersection of Gulf Road. Designed by Paul P. Cret. Cost $100,000. Dimensions, fifty feet high and forty feet wide at base. Material, granite. General George Washington Commander-in-Chief Painted by Col. TrunibuU from studies probably made at Valley Forge SECOND AND REVISED EDITION VALLEY FORGE A Chronicle of American Heroism FRANK H. TAYLOR Author and Illustrator JAMES W. NAGLE Publisher Issued under the direction of The Valley Forge Park Commission COPIES IN PAPER OR CLOTH May be had at Valley Forge Headquarters, from Philadelphia Book Stores and from Frank H. Taylor, or A. M. Slocum Co., 718 Arch St. Philadelphia Copyright, 1911 By FRANK H. TAYLOR INDEX PACK How to Reach Valley Forge I Important Features to be Seen at Valley Forge Park I Preface 5 The Valley Forge Park Commission and Its Work 6 The Song of Valley Forge 8 Chapter I—Valley Forge in 1777—Movements in the Campaign of 1777—Lord Howe's Advance on Philadelphia, 1777 9 Chapter II—-Impulse of the Valley Forge Centennial 13 Chapter III—The British Army in Philadelphia 16 Chapter IV—Occupation of Valley Forge—Washington's Military Family—The Headquarters Building \^ Chapter V—The Commander-in-Chief's -

Valley Forge Maintenance Volunteer Handbook a Guide to the Volunteers-In-Parks Program 4 Valley Forge Maintenance Volunteer Handbook TABLE of CONTENTS

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CompleteValley Forge site National name Historical Park Site1400 address North Outer Line Drive SecondKing of Prussia,line of PAaddress 19406 Third line of address EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA™ National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Valley Forge National Historical Park Valley Forge Maintenance Volunteer Handbook A Guide to the Volunteers-In-Parks Program 4 Valley Forge Maintenance Volunteer Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Welcome, and Thank you! A. Note from the Park Superintendent B. Note from Park VIP Coordinator C. Volunteer Testimonials 2. Forward A. Overview of the Onboarding Program 3. The National Park Service A. What is the National Park Service? B. The National Park System C. NPS Mission Statement D. NPS Centennial 4. The Volunteers In Parks (VIP) Program A. Volunteer Service Agreement B. Volunteer Safety/Risk Management C. Personal Liability While Working As a Volunteer D. What to Do if You Are Injured E. Discrimination F. Reimbursement G. Termination of Volunteer Agreement H. National Recognition of Volunteers I. Local Recognition and Engagement of Volunteers 5. Valley Forge National Historical Park A. Valley Forge NHP Mission Statement & Significance B. Timeline of Park Organizational History C. Organizational Structure of Valley Forge NHP D. Our Major Partners 6. Valley Forge Park Alliance 7. Valley Forge National Historical Park VIP Program A. Vision of VAFO VIP Program B. Mission of VAFO VIP Program C. VIP Program Goals D. Calendar of Events 8. Valley Forge Volunteer Opportunities 9. Volunteer Rights A view of Washington’s Headquarters during autumn. National Park Service 1 10. -

Open Space and Environmental Resource Protection Plan 2004 Update

OPEN SPACE AND ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE PROTECTION PLAN 2004 UPDATE UPPER MERION TOWNSHIP MONTGOMERY COUNTY, PA FINAL October 4, 2005 (First Draft April 1, 2005) (Revised Draft July 1, 2005) (Revised September 22, 2005) (Revised October 4, 2005) For: Upper Merion Township Open Space Committee Prepared by: Schoor DePalma Engineers and Consultants 1555 Bustard Road, Suite 50T Kulpsville, PA 19443-0304 Open Space and Environmental Resource Protection Plan 2004 Update – Upper Merion Township TABLE OF CONTENTS OPEN SPACE AND ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE PROTECTION PLAN 2004 UPDATE UPPER MERION TOWNSHIP MONTGOMERY COUNTY, PA Note: Items identified (A) are related to required plan elements as outlined in the Montgomery County Green Fields/Green Towns Program Recommendations, p 62. Table of Contents: Page: Project Participants…………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………….2 Community Background (A) …...…………………………………………………...3 Regional Setting Existing Patterns of Land Use Demographic Data Housing information Employment information Summary of existing relevant plans and policies Goals and Objective (B) …………………………………………………………….9 Existing Conditions and Resources………………………………………………...11 Permanently Protected Lands (C) Temporarily Protected Lands Schuylkill River Opportunities Public Park Inventories (C) Resource Considerations (D) + (F) Linkage Barriers & Opportunities (E) Open Space Needs………………………………………………………………….30 Growth evaluation & Build-out Scenario (G) Build-out Map Needs assessment and resource opportunities (H) Optional Plan -

Valley Forge National Historical Park

Valley Forge National Historical Park Valley Forge is full of great stories, now hear them come to life from the convenience of your cell phone! The cell phone tour is entirely self-guided: choose what you want to hear & when you want to hear it. Prompts are organized by Encampment Tour Stop. Enjoy! 1. Look for this symbol throughout the park. 2. Dial 484-396-1018 3. Enter the prompt number, followed by “#”. 4. Listen & enjoy! 5. Tell us what you think! Press 0 followed by “#” to record your feedback. 1. Visitor Center: General Visitor Information 6. Redoubt 3 11. The Museum Collections 61. The Inner Line of Defense 12. Park Archives & Library 62. The New Jersey Monument 13. The Encampment Store 63. Wildlife at Valley Forge 14. The Friends of Valley Forge Park 15. Volunteers in Parks (VIPs) 7. Artillery Park 2. The Muhlenberg Brigade: Log City 71. Henry Knox 72. Park Meadows 21. Oneida Indian Nation 73. Quartering During the Encampment 22. Topography & Industry 23. Bake Ovens 24. Redoubt 2 80. Varnum’s Quarters 81. General von Steuben 82. Soldiers on the Grand Parade 3. National Memorial Arch 83. Geology & Paleontology 31. The Pennsylvania Columns 32. Women in the Revolution 9. Washington Memorial Chapel 33. Yellow Springs Hospital 91. Details of the Chapel 34. George Washington’s Visit to Yellow Springs 92. Enlistment Slaves during the Revolution 93. Patriots of African Descent Monument 4. General Wayne Statue 41. Pennsylvania Regiments 42. Historic & Present Forests 43. Mount Joy Trails Scan this code with your QR Reader for a virtual business card 5. -

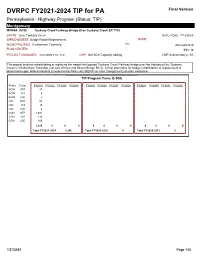

DVRPC FY2021-2024 TIP for PA

DVRPC FY2021-2024 TIP for PA Final Version Pennsylvania - Highway Program (Status: TIP) Montgomery MPMS# 16150 Tookany Creek Parkway Bridge Over Tookany Creek SR:7102 LIMITS: Over Tookany Creek Est Let Date: 7/13/2023 IMPROVEMENT Bridge Repair/Replacement NHPP: MUNICIPALITIES: Cheltenham Township FC: AQ Code:S19 PLAN CENTER: IPD: 16 PROJECT MANAGER: TSS/GANNETT/S. New CMP: Not SOV Capacity Adding CMP Subcorridor(s): 5G This project involves rehabilitating or replacing the weight-limit posted Tookany Creek Parkway bridge over the tributary of the Tookany Creek in Cheltenham Township, just east of New 2nd Street (Bridge Bill 2). A final alternative for bridge rehabilitation or replacement is determined upon federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or state Categorical Exclusion clearance. TIP Program Years ($ 000) Phase Fund FY2021 FY2022 FY2023 FY2024 FY2025 FY2026 FY2027 FY2028 FY2029 FY2030 FY2031 FY2032 ROW STP 47 ROW 183 9 ROW LOC 3 UTL STP 52 UTL 183 10 UTL LOC 3 CON STP 1,697 CON 183 318 CON LOC 106 2,245 0 0 0 00 0 0 00 0 0 Total FY2021-2024 2,245 Total FY2025-2028 0 Total FY2029-2032 0 7/27/2021 Page 112 DVRPC FY2021-2024 TIP for PA Final Version Pennsylvania - Highway Program (Status: TIP) Montgomery MPMS# 16214 PA 611, Old York Road Over SEPTAWest Trenton Line (Bridge) SR:0611 LIMITS: Over SEPTA West Trenton Line (Noble Station) Est Let Date: 4/14/2022 IMPROVEMENT Bridge Repair/Replacement NHPP: Y MUNICIPALITIES: Abington Township FC: 14 AQ Code:S19 PLAN CENTER: IPD: 20 PROJECT MANAGER: TSS/H. -

Valley Forge National Historical Park

Valley Forge National Historical Park Valley Forge is full of great stories, now hear them come to life from the convenience of your cell phone! The cell phone tour is entirely self-guided: choose what you want to hear & when you want to hear it. Prompts are organized by Encampment Tour Stop. Enjoy! 1. Look for this symbol throughout the park. 2. Dial 484-396-1018 3. Enter the prompt number, followed by “#”. 4. Listen & enjoy! 5. Tell us what you think! Press 0 followed by “#” to record your feedback. 1. Visitor Center: General Visitor Information 6. Redoubt 3 11. The Museum Collections 61. The Inner Line of Defense 12. Park Archives & Library 62. The New Jersey Monument 13. The Encampment Store 63. Wildlife at Valley Forge 14. The Friends of Valley Forge Park 15. Volunteers in Parks (VIPs) 7. Artillery Park 2. The Muhlenberg Brigade: Log City 71. Henry Knox 72. Park Meadows 21. Oneida Indian Nation 73. Quartering During the Encampment 22. Topography & Industry 23. Bake Ovens 24. Redoubt 2 80. Varnum’s Quarters 81. General von Steuben 82. Soldiers on the Grand Parade 3. National Memorial Arch 83. Geology & Paleontology 31. The Pennsylvania Columns 32. Women in the Revolution 9. Washington Memorial Chapel 33. Yellow Springs Hospital 91. Details of the Chapel 34. George Washington’s Visit to Yellow Springs 92. Enlistment Slaves during the Revolution 93. Patriots of African Descent Monument 4. General Wayne Statue 41. Pennsylvania Regiments 42. Historic & Present Forests 43. Mount Joy Trails Scan this code with your QR Reader for a virtual business card 5. -

Valley Forge National Historical Park Visitor Study

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Valley Forge National Historical Park Visitor Study Summer 2001 Report 130 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Valley Forge National Historical Park Visitor Study Summer 2001 Todd Simmons Margaret Littlejohn Visitor Services Project Report 130 May 2002 Todd Simmons was VSP Research Aide and Margaret Littlejohn is National Park Service VSP Coordinator, based at the Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Idaho. We thank the staff and volunteers of Valley Forge National Historical Park for their assistance with this study. The VSP acknowledges the Public Opinion Lab of the Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, Washington State University, for its technical assistance. Visitor Services Project Valley Forge National Historical Park Report Summary • This report describes the results of a visitor study at Valley Forge National Historical Park (NHP) during August 11-19, 2001. A total of 755 questionnaires were distributed to visitors. Visitors returned 550 questionnaires for a 72.8% response rate. • This report profiles Valley Forge NHP visitors. A separate appendix contains visitors' comments about their visit. This report and the appendix include summaries of those comments. • Forty percent of visitor groups were groups of two. Forty-six percent of the visitor groups were family groups. Fifty-two percent of visitors were aged 31-55 years and 21% were aged 15 or younger. • United States visitors were from Pennsylvania (53%), New Jersey (6%), New York (4%), 34 other states and Washington, D.C. Four percent of all visitors were international, with 16% from France, 13% from England, and 11% from Taiwan. -

Valley Forge Alternative Transportation Feasibility Study

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Valley Forge National Historical Park Valley Forge, Pennsylvania Valley Forge Alternative Transportation Feasibility Study Final Report PMIS No. 91449 June 2004 John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Research and Special Programs Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S ACRONYM(S) 11. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Valley Forge Landscape Valley Forge National Historical Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Valley Forge Landscape Valley Forge National Historical Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Valley Forge Landscape Valley Forge National Historical Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. -

VALLEY FORGE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK HABS No. PA-6186 Valley Forge National Historical Park Valley Forge Vicinity ^ Montgomery

VALLEY FORGE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK HABS No. PA-6186 Valley Forge National Historical Park Valley Forge Vicinity ^ Montgomery & Chester Counties HnC-O Pennsylvania a- WRITTEN HISTORICAL & DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of Interior 1849 C Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 INDEX TO PHOTOGRAPHS VALLEY FORGE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK HABS NO. PA-6186 (page 11) PA-6186-94 VIEW OF THE REMNANTS OF THE RECONSTRUCTED EARTHWORKS AT FORT WASHINGTON (REDOUBT #3), LOOKING SOUTHEAST WITH VIEWING PLATFORM IN FOREGROUND (Note reference to HABS No. PA-6186-93) PA-6186-95 Photocopy of historic photograph, VIEW OF ROADWAY FROM VALLEY FORGE RAILROAD STATION TO (FORMER) PICNIC GROUNDS, LOOKING NORTHEAST; LOCATION IS JUST ABOVE INTERSECTION WITH CONTINENTAL AVENUE PA-6186-96 VIEW OF ROADWAY FROM VALLEY FORGE RAILROAD STATION TO UPPER PARKING LOT, LOOKING NORTHEAST; LOCATION IS JUST ABOVE INTERSECTION WITH CONTINENTAL AVENUE (Note reference to HABS No. PA-6186-95) PA-6186-97 Photocopy of historic photograph, PERSPECTIVE VIEW OF VALLEY FORGE RAILROAD STATION, TRACKS AND COLONNADE, LOOKING WEST PA-6186-98 Photocopy of historic photograph, VIEW OF VALLEY FORGE RAILROAD STATION COLONNADE, LOOKING WEST-NORTHWEST PA-6186-99 Photocopy of historic postcard, VIEW OF OLD VALLEY FORGE RAILROAD STATION WITH TRAIN "ROUNDING THE CURVE," LOOKING EAST PA-6186-100 Photocopy of historic postcard, VIEW ENTITLED "VIEW ON THE SCHUYLKILL RIVER AT VALLEY FORGE STATION, PA." SHOWING OLD STATION, RIVER WITH PLEASURE BOAT, AND TOW PATH LOOKING EAST PA-6186-101 CURRENT VIEW FROM SAME VANTAGE POINT AS ABOVE, VIEW ALONG THE SCHUYLKILL RIVER NEAR VALLEY FORGE STATION, SHOWING RIVER AND TOW PATH, LOOKING EAST (Note reference to HABS No. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Valley Forge National Historical Park______________________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _______N/A____________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _Roughly bounded by Pawlings and Audubon roads, U.S. Route 422, Interstate 76, and Valley Creek_ City or town: _Lower Providence, Schuylkill, Tredyffrin, Upper Merion, and West Norriton State: _Pennsylvania__ County: _Montgomery; Chester_ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that