2018 NMUN-China General Assembly Background Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GGW 2021 One-Pager

September 17-26, 2021 #GlobalGoals From September 17-26, 2021, Global Goals Week will mobilize 2020 Overview communities, demand urgency, and supercharge solutions for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), whether it be digitally ● 63 million joined online or physically. Our shared future and the achievement of the Global ● 112 supporting partners Goals will be determined by our global solidarity – how we work together across borders, nationalities, sectors and generations. ● 164 events registered ● 17,500 people joined in person In 2015, 193 Member States of the United Nations made a universal ● Social media engagements: 527,000 promise to leave no one behind through the 17 SDGs. One year later, Project Everyone, UNDP and the United Nations Foundation came ● Social media impressions: 2.2 billion together to honor that promise by launching Global Goals Week, an annual week of action, awareness, and accountability for the SDGs. As the world still grapples with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, achieving the SDGs is more critical than ever - the Goals are the pathway to progress towards a safer and more equal world. As part of the Decade of Action to Deliver the SDGs, our coalition of over 100 partners will mobilize on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly High-level Week in September. This year, we will come together virtually and in-person to cultivate ideas, identify solutions, and build partnerships with the power to solve a wide range of complex global problems from poverty and gender to climate change and inequality. Join the movement. Get involved here. Global Goals Week events will engage people around the world in conversation and action. -

The Sentinel Period Ending 30 September 2017

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development __________________________________________________ Period ending 30 September 2017 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer-reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice, a program of the GE2P2 Global Foundation, which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor, The Sentinel President. GE2P2 Global Foundation [email protected] The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments -

Expo 2020 Dubai's Programme for People and Planet

EXPO 2020 DUBAI’S PROGRAMME FOR PEOPLE AND PLANET July 2021 | Final Draft Edition 1 PROGRAMME AT A GLANCE 2 PROGRAMME AT A GLANCE Expo 2020 Dubai’s Programme for People and Planet is designed to address the most pressing challenges we face as a world today by deploying the convening power of World Expos and the UAE to galvanise collective and meaningful action. Event series will run throughout the six months of Expo, the majority aligned with our 10 Theme Weeks (see over page). The Programme’s astonishing array of events and experiences is far-reaching and diverse. Large, public-facing Flagship events aim to raise awareness and galvanise action among the general public around each Theme Week’s focus area, while TED-style talks cover a myriad of topics for special-interest audiences. Underpinned by accessibility and inclusivity, the Programme also features Hybrid events. These blend physical gatherings with a virtual component, enabling policymakers, private-sector, civil-society actors, and the general public to come together, no matter where they are in the world. Additionally, a series of youth-focused events provides a vital platform for the generation that stands to benefit most from our Programme for People and Planet. 3 THEME WEEKS THEME WEEK FOCUS AREAS DATES - Climate change - Disaster risk management CLIMATE & - Circular and green economy 3-9 Oct, 2021 BIODIVERSITY - At-risk regions - Natural resource and biodiversity conservation - Space exploration SPACE - Governance and law 17-23 Oct, 2021 - Space data and remote sensing - -

2019 Overview Communities, Demand Urgency, and Supercharge Solutions • 106,500+ People Joined Online for the Global Goals, Whether It Be Digitally Or Physically

September 18-26, 2020 | #GlobalGoals From September 18-26, Global Goals Week will mobilize 2019 Overview communities, demand urgency, and supercharge solutions • 106,500+ people joined online for the Global Goals, whether it be digitally or physically. Our shared future and the achievement of the Global Goals will be • 30,000+ people participated in events determined by our global solidarity – how we work together • 73 events registered across borders, nationalities, sectors and generations. • 115 countries engaged 193 Member States of the United Nations made a universal • 54 languages spoken promise in 2015 to leave no one behind through 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). One year later, Project Everyone, • Social media reach: 5.8 billion UNDP and the United Nations Foundation came together to • Social media impressions: 52.7 million honor that promise by launching Global Goals Week, an annual week of action, awareness, and accountability for the SDGs. Today, we are at a turning point for the Global Goals, with 10 years left to achieve their vision, and COVID-19 causing devastating setbacks for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable. As part of the Decade of Action to Deliver the Global Goals, our coalition of 100 partners will mobilize on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly High-level Week to cultivate ideas, identify solutions, and hold leaders accountable. We have an opportunity to recover better and build a world that is fairer, more sustainable and more equal. Tackling climate action, providing access to healthcare and quality food, ensuring that all children have access to quality education, and protecting the most vulnerable are now more important than ever. -

GGW 2021 One-Pager

September 17-26, 2021 #GlobalGoals From September 17-26, 2021, Global Goals Week will mobilize 2020 Overview communities, demand urgency, and supercharge solutions for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), whether it be digitally ● 63 million joined online or physically. Our shared future and the achievement of the Global ● 112 supporting partners Goals will be determined by our global solidarity – how we work together across borders, nationalities, sectors and generations. ● 164 events registered ● 17,500 people joined in person In 2015, 193 Member States of the United Nations made a universal ● Social media engagements: 527,000 promise to leave no one behind through the 17 SDGs. One year later, Project Everyone, UNDP and the United Nations Foundation came ● Social media impressions: 2.2 billion together to honor that promise by launching Global Goals Week, an annual week of action, awareness, and accountability for the SDGs. As the world still grapples with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, achieving the SDGs is more critical than ever - the Goals are the pathway to progress towards a safer and more equal world. As part of the Decade of Action to Deliver the SDGs, our coalition of over 100 partners will mobilize on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly High-level Week in September. This year, we will come together virtually and in-person to cultivate ideas, identify solutions, and build partnerships with the power to solve a wide range of complex global problems from poverty and gender to climate change and inequality. Join the movement. Get involved here. Global Goals Week events will engage people around the world in conversation and action. -

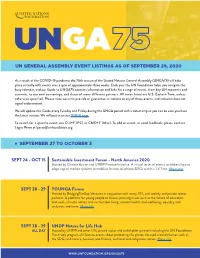

Un General Assembly Event Listings As of September 29, 2020

UNGA UN GENERAL ASSEMBLY EVENT LISTINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER 29, 2020 As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA75) will take place virtually with events over a span of approximately three weeks. Each year the UN Foundation helps you navigate the busy calendar, and our Guide to UNGA75 contains information and links for a range of events, from key UN moments and summits, to our own convenings, and those of many different partners. All times listed are U.S. Eastern Time, unless otherwise specified. Please note we can’t provide or guarantee invitations to any of these events, and inclusion does not signal endorsement. We will update this Guide every Tuesday and Friday during the UNGA period with a datestamp so you can be sure you have the latest version. We will post it on our UNGA page. To search for a specific event, use Ctrl+F (PC) or CMD+F (Mac). To add an event, or send feedback, please contact Legna Perez at [email protected] SEPTEMBER 27 TO OCTOBER 3 SEPT 24 - OCT 15 Sustainable Investment Forum - North America 2020 Hosted by Climate Action and UNEP Finance Initiative. A virtual series of events to address how to adapt capital market systems to mobilize finance to achieve SDGs within a 1.5° limit. More info SEPT 28 - 29 YOUNGA Forum Hosted by BridgingTheGap Ventures in conjuction with many UN, civil society and private sector partners. A platform for young people to discuss pressing issues such as the future of education and work, climate action and sustainable living, mental health and wellbeing, equality and inclusion, and more. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 24 July 2020

United Nations A/75/230 General Assembly Distr.: General 24 July 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 140 of the provisional agenda* Programme budget for 2020 United Nations Office for Partnerships Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report is submitted pursuant to General Assembly decisions 52/466 and 53/475, in which the Secretary-General was requested to inform the Assembly, on a regular basis, about the activities of the United Nations Office for Partnerships. It supplements the information contained in the previous reports of the Secretary- General (most recently, A/74/266). The Office serves as a global gateway for public-private partnerships to advance the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It oversees the areas set out below. The United Nations Fund for International Partnerships (UNFIP) was established in 1998 to serve as the interface between the United Nations Foundation and the United Nations system. At the end of 2019, the cumulative allocations as approved by the Foundation for UNFIP projects to be implemented by the United Nations system had reached approximately $1.47 billion. Of this amount, it is estimated that $0.45 b illion (about 30 per cent) represents core funds contributed by Ted Turner and $1.02 billion (about 70 per cent) was generated as co-financing from other partners. By the end of 2019, the total number of United Nations projects and programmes supported by the United Nations Foundation through UNFIP stood at 667, implemented by 48 United Nations system entities in 128 countries. The United Nations Democracy Fund was established by the Secretary-General in July 2005 to support democratization around the world. -

The Sentinel Period Ending 23 September 2017

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development __________________________________________________ Period ending 23 September 2017 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer-reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice, a program of the GE2P2 Global Foundation, which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor, The Sentinel President. GE2P2 Global Foundation [email protected] The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments -

General Assembly Distr.: General 31 July 2019

United Nations A/74/266 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 July 2019 Original: English Seventy-fourth session Item 136 of the provisional agenda* Programme budget for the biennium 2018–2019 United Nations Office for Partnerships Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report is submitted pursuant to General Assembly decisions 52/466 and 53/475, in which the Secretary-General was requested to inform the Assembly, on a regular basis, about the activities of the United Nations Office for Partnerships. It supplements the information contained in the previous reports of the Secretary- General (most recently, A/73/222). The Office serves as a global gateway for public-private partnerships to advance the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It oversees the areas set out below. The United Nations Fund for International Partnerships (UNFIP) was established in 1998 to serve as the interface between the United Nations Foundation and the United Nations system. At the end of 2018, the cumulative allocations as approved by the Foundation for UNFIP projects to be implemented by the United Nations system had reached approximately $1.46 billion. Of this amount, it is estimated that $0.45 billion (about 31 per cent) represents core funds contributed by Ted Turner and $1.01 billion (about 69 per cent) was generated as co-financing from other partners. The total number of United Nations projects and programmes supported by the Foundation through UNFIP stood at 657, implemented by 48 United Nations entities in 128 countries. The United Nations Democracy Fund was established by the Secretary-General in July 2005 to support democratization around the world. -

Expo 2020 Dubai's Programme for People and Planet

EXPO 2020 DUBAI’S PROGRAMME FOR PEOPLE AND PLANET March 2021 | 2nd Edition 1 MESSAGE FROM HER EXCELLENCY REEM AL HASHIMY, DIRECTOR GENERAL, EXPO 2020 DUBAI Dear friends and colleagues I am delighted to welcome you to the Second Edition of our Expo 2020 Dubai Programme Information Pack. Within these pages you will find all you need to know to engage purposefully and productively with our extensive series of events and experiences scheduled for the six months of Expo. You will also find a snapshot of an instant in time; another proud milestone on a shared journey that is rich with special and significant moments. From the bid phase and our selection as Host City, to the participation of more than 200 nations and International Organisations, to global solidarity in the wake of the pandemic and our postponement; at every I wish to thank you all, from our International step we have always been able to count on you, the Participants, to our In Association With and International Participants and our Official Partners, Commercial Partners, International Organisations, who believe in the profound generational impact of Non-Official Participants, everyone who has been our Expo. involved on the journey with us till now. Together with you we will inspire every visitor to become an active We seek not just to bring the world together, but to participant and to take personal responsibility for chart a course forward for that world. To stimulate collective impact. We will help reimagine the global one another in pursuit of a cleaner, safer and healthier economy through the lively exchange of new ideas future for all. -

Overview Global Goals Week 2018

Accelerating progress on the Sustainable Development Goals Global Goals Week is an annual week of action, awareness, and accountability for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Launched by Project Everyone, UNDP, and the United Nations Foundation in 2016, it brings together governments, businesses, individuals, international organizations, civil society, and others during the United Nations General Assembly in September to build momentum to achieve the SDGs and ensure no one is left behind. With more than 60 partners and growing, the power of collaboration is at the core of Global Goals Week. We come together to cultivate ideas, identify solutions, and generate meaningful partnerships for the SDGs. 2019 is a significant year for the SDGs. The UN Secretary-General will host a Climate Action Summit to boost ambition and accelerate action. The September High-level Political Forum under the auspices of UNGA will assess progress achieved since 2015 and provide guidance on the way forward. Now, more than ever, is the time to come together to hold leaders accountable and accelerate progress. OVERVIEW GLOBAL GOALS WEEK 2018 OVER 286,000 people joined online OVER 54 languages spoken OVER 70,000 people participated 60 supporting partners in Global Goals Week events OVER 127 countries engaged 44 events registered TWITTER Which SDGs were tweeted about? Top 20 Countries by # Tweets ANALYSIS FACTS Goal 1 - No Poverty 54,727 United States 60.2% Goal 2 - Zero Hunger 38,813 Nigeria 4.8% South Africa 2.8% 537,887 tweets Goal 3 - Health 78,697 India 2.8% Goal 4 - Education 44,555 United Kingdom 2.2% 461,57 retweets Goal 5 - Gender Equality 106,520 Pakistan 2.1% Goal 6 - Water 14,338 Germany 1. -

GGW 2021 One-Pager

September 17-26, 2021 #GlobalGoals From September 17-26, 2021, Global Goals Week will mobilize 2020 Overview communities, demand urgency, and supercharge solutions for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), whether it be digitally ● 63 million joined online or physically. Our shared future and the achievement of the Global ● 112 supporting partners Goals will be determined by our global solidarity – how we work together across borders, nationalities, sectors and generations. ● 164 events registered ● 17,500 people joined in person In 2015, 193 Member States of the United Nations made a universal ● Social media engagements: 527,000 promise to leave no one behind through the 17 SDGs. One year later, Project Everyone, UNDP and the United Nations Foundation came ● Social media impressions: 2.2 billion together to honor that promise by launching Global Goals Week, an annual week of action, awareness, and accountability for the SDGs. As the world still grapples with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, achieving the SDGs is more critical than ever - the Goals are the pathway to progress towards a safer and more equal world. As part of the Decade of Action to Deliver the SDGs, our coalition of over 100 partners will mobilize on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly High-level Week in September. This year, we will come together virtually and in-person to cultivate ideas, identify solutions, and build partnerships with the power to solve a wide range of complex global problems from poverty and gender to climate change and inequality. Join the movement. Get involved here. Global Goals Week events will engage people around the world in conversation and action.