Tenement Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

151 Canal Street, New York, NY

CHINATOWN NEW YORK NY 151 CANAL STREET AKA 75 BOWERY CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR Northeast corner of Bowery CANAL STREET SPACE 30 FT Ground Floor 2,600 SF Basement 2,600 SF 2,600 SF Sub-Basement 2,600 SF Total 7,800 SF Billboard Sign 400 SF FRONTAGE 30 FT on Canal Street POSSESSION BASEMENT Immediate SITE STATUS Formerly New York Music and Gifts NEIGHBORS 2,600 SF HSBC, First Republic Bank, TD Bank, Chase, AT&T, Citibank, East West Bank, Bank of America, Industrial and Commerce Bank of China, Chinatown Federal Bank, Abacus Federal Savings Bank, Dunkin’ Donuts, Subway and Capital One Bank COMMENTS Best available corner on Bowery in Chinatown Highest concentration of banks within 1/2 mile in North America, SUB-BASEMENT with billions of dollars in bank deposits New long-term stable ownership Space is in vanilla-box condition with an all-glass storefront 2,600 SF Highly visible billboard available above the building offered to the retail tenant at no additional charge Tremendous branding opportunity at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge with over 75,000 vehicles per day All uses accepted Potential to combine Ground Floor with the Second Floor Ability to make the Basement a legal selling Lower Level 151151 C anCANALal Street STREET151 Canal Street NEW YORKNew Y |o rNYk, NY New York, NY August 2017 August 2017 AREA FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS/BRANCH DEPOSITS SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LUDLOW STREET ESSEX STREET SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LEGEND LUDLOW -

113 Stanton Street

113 STANTON STREET BETWEEN LUDLOW & ESSEX STREET | LOWER EAST SIDE AS EXCLUSIVE AGENTS WE ARE PLEASED TO OFFER THE FOLLOWING RETAIL OPPORTUNITY FOR DIRECT LEASE: APPROXIMATE SIZE Ground Floor: 2,000 Square Feet Lower Level: 1,500 Square Feet FRONTAGE 20 Feet ASKING RENT $150 PSF POSSESSION Immediate TERM 10 Years NEIGHBORS Souvlaki GR, Beauty & Essex, Hotel on Rivington, Schiller’s, San Loco, El Sombrero, Mission Cantina, Hair of the Dog, Arlene’s Grocery, Pizza Beach, Ludlow Bar, The Meatball Shop, Russ & Daughters COMMENTS • All Uses Considered TRANSPORTATION CONTACT INFO JAMES FAMULARO JEFF GEOGHEGAN Retail Leasing Division - Senior Director Retail Leasing Division - Director [email protected] [email protected] 646.658.7373 646.658.7371 All information supplied is from sources deemed reliable and is furnished subject to errors, omissions, modifications, removal of the listing from sale or lease, and to any listing conditions, including the rates and manner of payment of commissions for particular offerings imposed by Eastern Consolidated. This information may include estimates and projections prepared by Eastern Consolidated with respect to future events, and these future events may or may not actually occur. Such estimates and projections reflect various assumptions concerning anticipated results. While East- ern Consolidated believes these assumptions are reasonable, there can be no assurance that any of these estimates and projections will be correct. Therefore, actual results may vary materially from these estimates and projections. Any square footage dimensions set forth are approximate. 20 WESTWOOD ROAD DESIGN CH CORNERSTONE Telephone: 718.757 2885 Telephone: 718.757 YONKERS NY 10710 ern Consolidated believes these assumptions are reasonable, there can be no assurance that any of these estimates and projections will be correct. -

20 Clinton Street, New York NY

Investment Opportunity Lower East Side New York RETAIL CONDOMINIUM AT 20 CLINTON STREET FOR LEASE OR SALE ASKING PRICE Exclusively Offered by RKF INVESTMENT SALES $2 M & ADVISORY SERVICES Executive Summary RKF Investment Sales & Advisory Services (“RKF”) has been retained as the exclusive agent for the sale of 20 Clinton Street, vacant retail condo with 1,250 SF on the Ground Floor and 450 SF in the Lower Level. The Property is situated mid-block with 28 FT of frontage along the east side of Clinton Street between Stanton and East Houston Streets in Manhattan’s historic Lower East Side. The property can accommodate black iron venting for food use. Investment Highlights DYNAMIC LOCATION Located in the Lower East Side, the property benefits from a market that is currently undergoing a dramatic makeover. There is a steady increase in pricing in both the residential and retail rents year-over- year in the Lower East Side, indicative of the market demand and robust market conditions. The neighborhood is “hip” for millennials and has also seen rising interest from families creating an eclectic mix of nightlife, music, art, upscale boutiques, hotels and high-end residential developments. Situated in close proximity to two subway stations with access to the B, D, F, M, J and Z subway lines make it ideal for the surrounding residential and retail developments. NEW DEVELOPMENT Driving the transformation is the $1.1 billion mixed-use Essex Crossing mega project, which is set to deliver 1,100 residential units along with 350,000 SF of office space and 450,000 SF of retail across ten buildings. -

I30 Allen Street I30 Allen Street Lower East Side

I30 ALLEN STREET I30 ALLEN STREET LOWER EAST SIDE As one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, the Lower East Side is currently undergoing rapid change that has resulted in an area of boutique shops, luxury hotels and authentic NY restaurants. This neighborhood has a dynamic, creative vibe (exemplified by the many contemporary art galleries in the neighborhood) as well as striking diversity. LISTING SPECS PRIME FEATURES Ground Fl: Approx. 520 SF • Great frontage (over 25 FT) Ceilings: Approx. 12 FT • Brand new glassfront Term: 10 Years • Polished concrete floor Possession: Immediate • Exposed brick walls Asking Rent: Request SUGGESTED USE NEIGHBORS TRANSPORTATION • Office • Russ & Daughters 2nd Ave • Café • Lucky Jack’s • Art Gallery • 10Below Ice Cream Delancey • Fashion • Starbucks • Perrotin New York FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT: TARIK BOUZOURENE [email protected] 212.732.5692 Ext. 908 164 LUDLOW STREET NEW YORK, NY 10002 WWW.REALNYPROPERTIES.COM A o s Y h i o c Gr e r y m y & r N a v y e B k r ea t c M u r r e y s PR i’azyz a B u r k i n a L o u n g e ELAITNEDISER l e m e n t T hWOLDUL i n EHT k P i n k S u g a r C a f e TS 32 ,TINU 342 ,YRO L TNER YRUXU GNIDLIUB LA Lo bster Joint THE THOMPSON aireuqaT s’onimoDRuss & Daughters HOTEL, LES ooZ hcrA WOLDUL LETOH yrolG & stirG SMOOR 261 ,YROTS 02 Blue 1 ileD ykcuL 41 ROOM nobbiR ihsuS occaB iD anrevaTevissesbO ehT S ehT evislupmoC ESSEX STREETalasaM ORCHARD STREETseidooH OGIDNI LETOHscitemsoC LUDLOpohS W STREETTEERTS DRAHCRO 081 alaW MOORS 051 ,YROTS 42 sratiuG wolduL -

198 Rivington Street Marketing Package V4.Indd

198 RIVINGTON STREET ARTISTS RENDERING OF SPACE Burkina Navy Army & Army Daughters Russ & Russ 196 RESIDE THE LUDLOW n 23 STORY, 243 UNIT, k LUXURY RENTAL BUILDING Pala STREET ORCHARD O Blue STREET LUDLOW f ESSEX STREET ESSEX Dirty French STREET RFOLK Rockwood Ribbon Zoo e Music Hall Sushi Arch HOTEL LUDLOW F 20 STORY, 162 ROOMS Claw Grit & STREET OLK Daddy’s NYC THE Glory L THOMPSON Prohibition Bakery STREET INTON Black Tap The HOTEL The Station Sweet Chick E 141 ROOMS Masala Hoodies Independent Y STREET Grilled Shop Taverna Di Bacco Obsessive Wala Cheese Project Compulsive E HOTEL INDIGO T Quinn Noi 180 ORCHARD STREET | 24 STORY, 296 ROOMS Cosmetics Konditori Jewlery Synchronicity Tre Wholes FS Rehearsal Studios Rehearsal FISH I Till The Skinny No Fun Rivington Assembly New York S Why Not Bar & Lounge NYC anctuary Coffee Stanton 176 S Ivan Ramen Balvanera The Rising States Foods ale eptember Epstein’s A Casa FoxRosario’s Cantina Mission Frankie El Re El Wines Lowlife Pizza ODD Cocoa Bar Maple Music Lili’s y El Sombrero Tapeo 29 STANTON STREET STANTON STREET The Dog The Hair Of Hair Grocery Arlene’s Social Stanton Cafe Bisous Prema STANTON STREET Loco San A. Turen Pizza Shop Flower Clinton STANTON STREET M SITE 10 - 2022 - 10 SITE ESSEX CROSSING ESSEX Chari & Co. N Co. & Chari Yumi Kim El Nuevo Community Gall Totah STANTON STREET Beach condos rate arket Donnybrook Amaneer Healthcare Cook Center Pianos Restaurant Network Grammer School Tiny Fox Contra AREA MAP e All My Children’s Stop Saka Norfolks Atlas Cafe ry Dee Basement Barber Shop -

191 ORCHARD STREET 2,500 SF Available for Lease Between East Houston and Stanton Streets LOWER EAST SIDE NEW YORK | NY SPACE DETAILS

RETAIL SPACE 191 ORCHARD STREET 2,500 SF Available for Lease Between East Houston and Stanton Streets LOWER EAST SIDE NEW YORK | NY SPACE DETAILS GROUND FLOOR LOCATION NEIGHBORS Between East Houston and Equinox (coming soon), CVS Stanton Streets (coming soon), Blue Ribbon Sushi, Katz’s Delicatessen, Mr. Purple, SIZE SIXTY Hotel, Black Tap, The Meatball Ground Floor Approx 2,500 SF Shop, Georgia’s Eastside BBQ Basement Approx 1,500 SF BACKYARD COMMENTS FRONTAGE Prime Lower East Side restaurant/ retail opportunity Orchard Street Approx 45 FT Fully vented for cooking use POSSESSION Immediate Large backyard included RENT All uses considered Upon Request New long term lease, no key money 45 FT ORCHARD STREET BASEMENT TRANSPORTATION 2017 Ridership Report Second Avenue Bowery Station J Annual 5,372,036 Annual 1,327,970 Weekday 16,675 Weekday 3,715 Weekend 20,998 Weekend 7,018 AREA RETAIL TEET EAST FIRST STREET EAST 1 ST STREET EAST HOUSTON STREET 191 ORCHARD STON EAST HOUSTON EAST HOUSTON STREET STREET EAST HOUSTON EAST HO EAST HOUSTON STREET USTON EAST HOUSTON STREET THE BurkinaEAST HOUSTONArmy & EAST HOUSTON RIDGE Navy 196 ORCHARD Think EAST H Think Pink Think Burkina Navy Army & Army Element Daughters R Lounge Pink Mercury Remedy Gaia Italian Cafe Italian Gaia Remedy Diner Remedy HOTEL Russ & us 196 ORCHARD iLiL Laboratorio Laboratorio Element ABC Playground Daughters& s Del Gelato Gelato Diner MezettoMezetto rrs Mercury ABC Playground RESIDENTIAL Lounge DE THE LUDLOW ViviVivi Tea Tea 23 STORY, 243 UNIT, ORCHARD STREET ORCHARD LUXURY RENTAL -

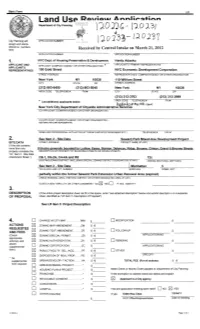

Zoning Text Amendment (ZR Sections 74-743 and 74-744) 3

UDAAP PROJECT SUMMARY Site BLOCK LOT ADDRESS Site 1 409 56 236 Broome Street Site 2 352 1 80 Essex Street Site 2 352 28 85 Norfolk Street Site 3 346 40 (p/o) 135-147 Delancey Street Site 4 346 40 (p/o) 153-163 Delancey Street Site 5 346 40 (p/o) 394-406 Grand Street Site 6 347 71 178 Broome Street Site 8 354 1 140 Essex Street Site 9 353 44 116 Delancey Street Site 10 354 12 121 Stanton Street 1. Land Use: Publicly-accessible open space, roads, and community facilities. Residential uses - Sites 1 – 10: up to 1,069,867 zoning floor area (zfa) - 900 units; LSGD (Sites 1 – 6) - 800 units. 50% market rate units. 50% affordable units: 10% middle income (approximately 131-165% AMI), 10% moderate income (approximately 60-130% AMI), 20% low income, 10% senior housing. Sufficient residential square footage will be set aside and reserved for residential use in order to develop 900 units. Commercial development: up to 755,468 zfa. If a fee ownership or leasehold interest in a portion of Site 2 (Block 352, Lots 1 and 28) is reacquired by the City for the purpose of the Essex Street Market, the use of said interest pursuant to a second disposition of that portion of Site 2 will be restricted solely to market uses and ancillary uses such as eating establishments. The disposition of Site 9 (Block 353, Lot 44) will be subject to the express covenant and condition that, until a new facility for the Essex Street Market has been developed and is available for use as a market, Site 9 will continue to be restricted to market uses. -

Name Website Address Email Telephone 11R Www

A B C D E F 1 Name Website Address Email Telephone 2 11R www.11rgallery.com 195 Chrystie Street, New York, NY 10002 [email protected] 212 982 1930 Gallery 14th St. Y https://www.14streety.org/ 344 East 14th St, New York, NY 10003 [email protected] 212-780-0800 Community 3 4 A Gathering of the Tribes tribes.org 745 East 6th St Apt.1A, New York, NY 10009 [email protected] 212-777-2038 Cultural 5 ABC No Rio abcnorio.org 156 Rivington Street , New York, NY 10002 [email protected] 212-254-3697 Cultural 6 Abrons Arts Center abronsartscenter.org 456 Grand Street 10002 [email protected] 212-598-0400 Cultural 7 Allied Productions http://alliedproductions.org/ PO Box 20260, New York, NY 10009 [email protected] 212-529-8815 Cultural Alpha Omega Theatrical Dance Company, http://alphaomegadance.org/ 70 East 4th Street, New York, NY 10003 [email protected] Cultural 8 Inc. 9 Amerinda Inc. (American Indian Artists) amerinda.org 288 E. 10th Street New York, NY 10009 [email protected] 212-598-0968 Cultural 10 Anastasia Photo anastasia-photo.com 166 Orchard Street 10002(@ Stanton) [email protected] 212-677-9725 Gallery 11 Angel Orensanz Foundation orensanz.org 172 Norfolk Street, NY, NY 10002 [email protected] 212-529-7194 Cultural 12 Anthology Film Archives anthologyfilmarchives.org 32 2nd Avenue, NY, NY 10003 [email protected] 212-505-5181 Cultural 13 ART Loisaida / Caroline Ratcliffe http://www.artistasdeloisiada.org 608 East 9th St. #15, NYC 10009 [email protected] 212-674-4057 Cultural 14 ARTIFACT http://artifactnyc.net/ 84 Orchard Street [email protected] Gallery 15 Artist Alliance Inc. -

District BN School Name Address City State Zip Principal Name 01 M015

Schools without Electricity as of 5:00pm on November 2nd, 2012 District BN School Name Address City State Zip Principal Name 01 M015 P.S. 015 Roberto Clemente 333 EAST 4 STREET MANHATTAN NY 10009 Irene Sanchez 01 M019 P.S. 019 Asher Levy 185 1 AVENUE MANHATTAN NY 10003 Jacqueline Flanagan 01 M301 Technology, Arts, And Sciences Studio 185 1 AVENUE MANHATTAN NY 10003 James Lee 01 M020 P.S. 020 Anna Silver 166 ESSEX STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Joyce Stallings Harte 01 M539 New Explorations Into Science, Technology And Math High School 111 COLUMBIA STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Darlene Despeignes 01 M378 School For Global Leaders 145 STANTON STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Marlon L. Hosang 01 M509 Marta Valle High School 145 STANTON STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Karen Feuer 01 M515 Lower East Side Preparatory High School 145 STANTON STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Loretta Caputo 01 M034 P.S. 034 Franklin D. Roosevelt 730 EAST 12 STREET MANHATTAN NY 10009 Melissa Rodriguez 01 M292 Henry Street School For International Studies 220 HENRY STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Esteban Barrientos 01 M332 University Neighborhood Middle School 220 HENRY STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Rhonda Levy 01 M345 Collaborative Academy Of Science, Technology, & Language-Arts Education 220 HENRY STREET MANHATTAN NY 10002 Iris Chiu, I.A. 01 M315 The East Village Community School 610 EAST 12 STREET MANHATTAN NY 10009 Mary Pree 01 M361 The Children'S Workshop School 610 EAST 12 STREET MANHATTAN NY 10009 Christine Loughlin 01 M063 The Star Academy – P.S.63 121 EAST 3 STREET MANHATTAN NY 10009 George Morgan 01 M363 Neighborhood School 121 EAST 3 STREET MANHATTAN NY 10009 Robin Williams 01 M064 P.S. -

Download (PDF)

SELECT FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS (TO SEE REPORT FOR FULL SET OF FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS, VISIT WWW.LESREADY.ORG) • The lack of damage from Hurricane Irene, the RECOMMENDATIONS FINDING 1. previous year, lulled residents into a false sense “We heard it [Hurricane Sandy] was The majority of LES residents of security. coming and we were asked to FOR NEW YORK CITY did not evacuate before • Of those that did evacuate, most did not utilize evacuate but didn’t because City shelters. the news made Sandy look GOVERNMENT: just like Irene in terms of Hurricane Sandy hit and o Only 15% went to a public shelter/ severity levels.” – Focus many decided to “shelter in evacuation center in NYC; group participant • Should make sure people are prepared to evacuate and that place.” o 71% went to friend or family’s house in NYC. buildings have information with regard to where people can evacuate. • Should provide transportation so people can evacuate. • Should assure the public that shelters are safe and properly NYCHA RESIDENTS staffed and put protocols in place that provide people with safety and security. FINDING 2. ZONE A RESIDENTS • Must ensure that information at shelters and about the Residents of the Lower East availability of shelters is available in at least Mandarin, Side were severely impacted *These percentages refer Cantonese, Spanish and Russian languages. by Hurricane Sandy. to the total number of residents surveyed. • Should make all notices, flyers and announcements available in, at minimum, Spanish, Chinese and Russian, the most LES Ready, also known as the Lower East Side Long Term common languages of Lower East Side residents in addition 98% of survey respondents report Recovery Group, is a coalition of community groups and to English as well as any other languages that are prevalent that they were affected by Hurricane institutions that will cooperatively coordinate our response, in a given community. -

Stanton Streetstanton Street A

STANTON 9 STREET BETWEEN CHRYSTIE ST & BOWERY | LOWER EAST SIDE EAST HOUSTON STREET Sugar Russ & East Mezetto The Gatsby Hotel Fools Gold Houston Café Daughters Hotel Macando Army & Navy myplasticheart Mole Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects Saphire Lounge Pala Rockwood STANTON Flower Girl Music Hall Bowery and Vine Blue Ribbon Sushi Izakaya Fred NYC Paulaner Brewery Los Perros Locos Lisson Gallery Rockwood Stage STREET Taylor Cruther's Studio Rooster Galler Nativity Mission Center Claw Daddy's New York Worldwide Restaurant Equipment 9 bOb Bar Soho Contemporary Art Quinn Sperone Westwater Konditori Noi Grit n Glor BETWEEN CHRYSTIE ST & BOWERY Whynot Coee Una Pizza Napoletana The Skinny Albanese Meats & Poultry Rosario's LOWER EAST SIDE Pizza CHRYSTIE STREET CHRYSTIE CHRYSTIE STREET CHRYSTIE Symbo STANTON STREETSTANTON STREET A. Turen Hair of Leave Rochelle 205 Frosche & Dacia Fusion Arts the Dog Cata Out of It Club Portman Gallery Museum Bikram Yoga • Turn-key Dry Cleaners La Gamelle Apizz Blue Stockings Restaurant Van Doren Waxter Mr. Taka Ramen Wassail Rayuela Manhattan Ehvonnae PRINCE STREET et al. Unisex People Restaurant 3 Sixteen Yaf Sparkle Shut The Box Self Edge Nena Resurrection Orchard Corsets Y Plank Pilates Studio The 155 Gallery SARA D Ted's Formal Wear Bowery Mission Copper and Oak S&A Fashion ROOSEVELT Forsyth Sandwich Askan & Coee Reed Space Karaoke Boho SIZE 400 SF Well Connected R BOWE PARK Republic Capital Krause Gallery Invisible NYC Wood Shoppe Katra Killion Epaulet Da Rucci FRONTAGE 9’ EZ Mini Broadway Iconic Exterminating -

274 Bowery, New York NY

BOWERY NEW YORK NY 274 BOWERY SPACE DETAILS LOCATION SITE STATUS West block between East Houston and Prince Streets Formerly Cooking Ideal LLC APPROXIMATE SIZE NEIGHBORS Ground Floor 2,140 SF Supreme, KITH, Whole Foods Market, Vans Vault, October’s Very Own, Storage Basement 1,100 SF Trek Bicycles, Patagonia, Nudie Jeans, John Varvatos, Reformation, Filson, 3.1 Philip Lim, Camper, Wells Fargo, and rag & bone POSSESSION COMMENTS Immediate At the nexus of SoHo, NoLIta, NoHo, the East Village and Lower East Side TERM Steps from Bowery Hotel, Public Hotel, CitizenM, Sister City by Ace Hotel Long term and The Moxy Hotel (coming soon) FRONTAGE Across from Whole Foods Market and The New Museum 20 FT on Bowery All uses accepted, with a venting plan in place CEILING HEIGHT Ground Floor 10 FT GROUND FLOOR 2,140 SF 20 FT BOWERY BOWERY NEW YORK, NY EAST 9TH STREET R 8TH STREET W MEN WOMEN ASTOR PLACE COOPER SQUARE 7TH STREET Cozy Soup n' Burger Semson Warehouse Wines & Spirits Alan Moss THIRD AVENUE Donut Pub NYC Sole Astor Place Theater FIRST AVENUE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SECOND AVENUE 6TH STREET NEW YORKBOOKSTORE UNIVERSITY BOOKSTORE(coming soon) NEW YORK UNIVERSITY MERCER STREET Sta Travel Colors Dienst + Dotter 5TH STREET NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Lost City Arts Build EAST 4TH STREET Studio NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Organic HOUSING Lafayette Cafè House B-Bar Mile High Swift Running Club Wise Men Evolution AREA RETAIL In-Living Le Basket Stereo GREAT JONES STREET VIC’s EAST 3RD STREET Dear Eva Rivington Presenhuber Hardware Bohemian True Value Gemma BIA BOWERY The Future Project Gino Sorbillo Pizza Gene BROADWAY Frankel Burkelman BondST Theatre DeVOL Kitchen Mish BOND STREET OVO Blades Paula EAST 2ND STREET Rubenstein Body Maria Trash Evolved Fancy GREAT JONES ALLEY LAFAYETTE STREETLAFAYETTE Grand Central Eyes on Kitchen and Bath Broadway Gjelina Adore Floral Inc.