Conference Papers (Alphabetical Order)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Fakulta Tělesné Kultury PLAVECKÁ DISCIPLÍNA 100 M ZNAK ŽENY V OBDOBÍ 2000-2013 Bakalářs

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Fakulta tělesné kultury PLAVECKÁ DISCIPLÍNA 100 M ZNAK ŽENY V OBDOBÍ 2000-2013 Bakalářská práce Autor: Kateřina Zátopková, TV-MV Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Dub Olomouc 2014 Jméno a příjmení autora: Kateřina Zátopková Název závěrečné práce: Plavecká disciplína 100 m znak ženy v letech 2000-2013 Pracoviště: Katedra sportu Vedoucí: Mgr. Jiří Dub Rok obhajoby: 2014 Abstrakt: Bakalářská práce se zabývá analýzou plaveckého způsobu znak v disciplíně 100 m v kategorii mužů a žen na světových a evropských soutěžích v 50m a v 25m bazénu v období 2000-2013. Dále rozebírá světové a evropské rekordy, výkony medailistů na olympijských hrách, mistrovství světa, mistrovství Evropy ve sledovaném období. Počty startujících závodníků, jejich věk a zpracovává úspěšnost prvních pěti plavců v disciplíně 100 m znak světových tabulek v ostatních olympijských disciplínách. Klíčová slova: plavání, plavecký způsob znak, plavecká disciplína 100 m znak Souhlasím s půjčováním bakalářské práce v rámci knihovních služeb. Author’s first name and surname: Kateřina Zátopková Title of the thesis: A swimming event 100 m backstroke women in years from 2000 to 2013 Department: Department of sport Supervisor: Mgr. Jiří Dub The year of presentation: 2014 Abstract: This bachelor thesis deals with development of backstroke in discipline 100 m for men and women in the world and European competitions in 50 m and 25 m pools in period 2000-2013. Further analyzes of world and European records, performance of medalists at the Olympics, World Championships, European Championships in the monitored period. The numbers of competitors, their age and processes success of the first five swimmers in discipline 100 m swimming character world tables in other Olympic disciplines. -

Len European Championships Aquatic Finalists

LEN EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS AQUATIC FINALISTS 1926-2016 2 EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS GLASGOW 2ND-12TH AUGUST 2018 SWIMMING AT TOLLCROSS INTERNATIONAL SWIMMING CENTRE DIVING AT ROYAL COMMONWEALTH POOL, EDINBURGH ARTISTIC (SYNCHRONISED) SWIMMING AT SCOTSTOUN SPORTS CAMPUS, GLASGOW OPEN WATER SWIMMING IN LAKE LOMOND 2 Contents Event Page Event Page European Championship Venues 5 4x100m Freestyle Team- Mixed 123 4x100m Medley Team – Mixed 123 50m Freestyle – Men 7 100m Freestyle – Men 9 Open Water Swimming – Medals Table 124 200m Freestyle – Men 13 400m Freestyle – Men 16 5km Open Water Swimming – Men 125 800m Freestyle – Men 20 10km Open Water Swimming – Men 126 1500m Freestyle – Men 21 25km Open Water Swimming – Men 127 50m Backstroke – Men 25 5km Open Water Swimming – Women 129 100m Backstroke – Men 26 10km Open Water Swimming – Women 132 200m Backstroke – Men 30 25km Open Water Swimming – Women 133 50m Breaststroke – Men 34 Open Water Swimming – Team 5km Race 136 100m Breaststroke – Men 35 200m Breaststroke – Men 38 Diving – Medals Table 137 50m Butterfly – Men 43 1m Springboard – Men 138 100m Butterfly – Men 44 3m Springboard – Men 140 200m Butterfly – Men 47 3m Springboard Synchro - Men 143 10m Platform – Men 145 200m Individual Medley – Men 50 10m Platform Synchro – Men 148 400m Individual Medley – Men 54 1m Springboard – Women 150 4x100m Freestyle Team – Men 58 3m Springboard – Women 152 4x200m Freestyle Team – Men 61 3m Springboard Synchro – Women 155 4x100m Medley Team – Men 65 10m Platform – Women 158 10m Platform Synchro – Women 161 -

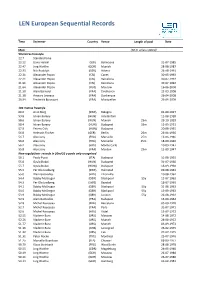

LEN European Sequential Records

LEN European Sequential Records Time Swimmer Country Venue Length of pool Date Men: (50 m unless stated) 50 metres freestyle 22.7 Standard time 22.52 Dano Halsall (SUI) Bellinzona 21-07-1985 22.47 Jorg Woithe (GDR) Munich 28-08-1987 22.33 Nils Rudolph (GER) Athens 24-08-1991 22.31 Alexander Popov (CSI) Canet 30-05-1992 22.21 Alexander Popov (CSI) Barcelona 30-07-1992 21.91 Alexander Popov (CSI) Barcelona 30-07-1992 21.64 Alexander Popov (RUS) Moscow 16-06-2000 21.50 Alain Bernard (FRA) Eindhoven 23-03-2008 21.38 Amaury Leveaux (FRA) Dunkerque 26-04-2008 20.94 Frederick Bousquet (FRA) Montpellier 26-04-2009 100 metres freestyle 60.0 Arne Borg (SWE) Bologna 04-09-1927 59.8 Istvan Barany (HUN) Amsterdam 11-08-1928 58.6 Istvan Barany (HUN) Munich 25m 29-10-1929 58.4 Istvan Barany (HUN) Budapest 33m 12-05-1931 57.8 Ferenc Csik (HUN) Budapest 20-08-1935 56.8 Helmuth Fischer (GER) Berlin 25m 26-04-1936 56.7 Alex Jany (FRA) Marseille 25m 12-06-1946 56.6 Alex Jany (FRA) Marseille 25m 18-09-1946 56.2 Alex Jany (FRA) Monte Carlo 10-09-1947 55.8 Alex Jany (FRA) Menton 25m 15-09-1947 New regulations- records in 50m/55 y pools only recognised 56.1 Paolo Pucci (ITA) Budapest 31-08-1955 55.8 Gyula Dobai (HUN) Budapest 31-07-1960 55.7 Gyula Dobai (HUN)) Budapest 18-09-1960 55.5 Per Ola Lindberg (SWE) Halmstad 09-08-1961 55.0 Alain Gottvalles (FRA) Thionville 10-08-1962 54.4 Bobby McGregor (GBR) Blackpool 55y 13-07-1963 54.3 Per Ola Lindberg (SWE) Baastad 18-07-1963 54.1 Bobby McGregor (GBR) Blackpool 55y 31-08-1963 54.0 Bobby McGregor (GBR) Blackpool 55y -

Laure Manaudou : « Ne Rien D’Europe Des 200 Et 400 M) Contribuer À Asseoir La Nouvelle Regretter » Dimension Internationale De La 8

MAG N138:Mise en page 1 7/12/12 10:48 Page 1 Magazine PREMIER SUR LA NATATION www.ffnatation.fr Rencontre > Francis Luyce page 10 Chartres 2012 5 Euros Hommage > Disparition de Christian Donzé Vague bleue page 20 Dossier 2012 | - décembre | Novembre > Rétrospective 2012 à domicile page 38 Numéro 138 Numéro MAG N138:Mise en page 1 7/12/12 10:48 Page 3 3 Édito (KMSP) Assumer, sans triompher ! 138 Magazine heure du bilan est arrivée, fin d’année et nouveau mandat obligent ! A dire vrai, ce n’est pas un moment facile. Non pas parce que le bilan n’est pas satisfaisant, bien au contraire, L’ mais parce que pour l’acteur et le passionné que je suis, il est délicat de dresser, en www.ffnatation.fr toute objectivité, un bilan aussi élogieux. Il convient, en effet, d’éviter le piège de l’autosatisfaction. Mon enthousiasme naturel et ma passion pour les joutes aquatiques pourraient aisément m’y Natation Magazine conduire. Je le sais. N°138 • Novembre - décembre 2012 Edité par la Fédération Française Je me contenterai donc de vous rappeler quelques chiffres éloquents. D’abord celui des Jeux de Natation. TOUR ESSOR 93, Olympiques de Londres, où les nageurs de l’équipe de France ont glané sept médailles, dont 14 rue Scandicci, 93 508 PANTIN. quatre titres, nous propulsant au troisième rang mondial, derrière les Etats-Unis et la Chine. Tél. : 01.41.83.87.70 Et puis il y a aussi les moissons records des championnats d’Europe de Budapest et ses vingt-trois Fax : 01.41.83.87.69 récompenses continentales, et les onze distinctions des championnats du monde de Shanghai et www.ffnatation.fr ses deux titres masculins ex-aequo (Camille Lacourt et Jérémy Stravius sur 100 m dos). -

Hoofdblad IE 20 Mei 2020

Nummer 21/20 20 mei 2020 Nummer 21/20 2 20 mei 2020 Inleiding Introduction Hoofdblad Patent Bulletin Het Blad de Industriële Eigendom verschijnt The Patent Bulletin appears on the 3rd working op de derde werkdag van een week. Indien day of each week. If the Netherlands Patent Office Octrooicentrum Nederland op deze dag is is closed to the public on the above mentioned gesloten, wordt de verschijningsdag van het blad day, the date of issue of the Bulletin is the first verschoven naar de eerstvolgende werkdag, working day thereafter, on which the Office is waarop Octrooicentrum Nederland is geopend. Het open. Each issue of the Bulletin consists of 14 blad verschijnt alleen in elektronische vorm. Elk headings. nummer van het blad bestaat uit 14 rubrieken. Bijblad Official Journal Verschijnt vier keer per jaar (januari, april, juli, Appears four times a year (January, April, July, oktober) in elektronische vorm via www.rvo.nl/ October) in electronic form on the www.rvo.nl/ octrooien. Het Bijblad bevat officiële mededelingen octrooien. The Official Journal contains en andere wetenswaardigheden waarmee announcements and other things worth knowing Octrooicentrum Nederland en zijn klanten te for the benefit of the Netherlands Patent Office and maken hebben. its customers. Abonnementsprijzen per (kalender)jaar: Subscription rates per calendar year: Hoofdblad en Bijblad: verschijnt gratis Patent Bulletin and Official Journal: free of in elektronische vorm op de website van charge in electronic form on the website of the Octrooicentrum Nederland. -

Advance Technical Program

Advance Technical Program Conferences: 17–20 March 2008 Courses: 16–20 March 2008 Exhibition: 18–20 March 2008 Orlando World Center Marriott Resort & Convention Center Orlando, Florida USA NETWORK WITH PEERS — HEAR THE LATEST RESEARCH MATERIALS · TECHNOLOGY · DEVICES · SYSTEMS Imaging, Sensors, and Displays Sensor Data Analysis IR SENSORS AND SYSTEMS ENGINEERING SENSOR DATA EXPLOITATION AND TARGET RECOGNITION HOMELAND SECURITY AND LAW ENFORCEMENT INFORMATION FUSION, DATA MINING, AND INFORMATION NETWORKS TACTICAL SENSORS AND IMAGERS SIGNAL, IMAGE, AND NEURAL NET PROCESSING CHEMICAL BIOLOGICAL RADIOLOGICAL NUCLEAR AND EXPLOSIVES (CBRNE) COMMUNICATION AND NETWORKING TECHNOLOGIES AND SYSTEMS MILITARY AND AVIONIC DISPLAYS PLUS SPACE TECHNOLOGIES AND OPERATIONS MODELING AND SIMULATION INTELLIGENT AND UNMANNED/UNATTENDED SENSORS AND SYSTEMS ENABLING PHOTONIC TECHNOLOGIES Advance Technical Conferences: 17–20 March 2008 Courses: 16–20 March 2008 Program Exhibition: 18–20 March 2008 Orlando World Center Marriott Resort & Convention Center Orlando, Florida USA NETWORK WITH PEERS — HEAR THE LATEST RESEARCH Attend the defense industry’s leading meeting SPIE Defense+Security brings together leading scientists and engineers from industry, military, and academia doing cutting-edge work in materials, technology, systems, and devices. Collaborate with your colleagues Network with leaders in the defense community. Join representatives from the US Navy, Army and Air Force, DARPA, Lockheed Martin, NASA, Raytheon, and other top organizations. Keep your technical edge through courses Gain practical insight from the top researchers and engineers in IR sensors and systems engineering, homeland security and law enforcement, and other key areas. Great teachers offer a wide range of introductory, intermediate, and advanced courses that will help you stay at the forefront of chemical and biological detection, laser radar, sensors, and more than 30 other topics. -

MEN's LONG COURSE WORLD RANKINGS Top 3 Performances 1948 to 1999 - (50 M Pool)

MEN'S LONG COURSE WORLD RANKINGS Top 3 Performances 1948 to 1999 - (50 M Pool) 50 M Freestyle Libre / Freistil / Livre Libres / Libero / Frisim 1980 0:22.71 Joe Bottom, USA 0:22.83 Bruce Stahl, USA 0:22.86 Gary Schatz, USA 1981 0:22.54 Robin Leamy, USA 0:22.84 Bruce Stahl, USA 0:22.86 Boyd Crisler, USA 1982 0:22.69 Peng-Siong Ang, SIN 0:22.74 Jorg Woithe, GDR 0:22.78 Rowdy Gaines, USA 1983 0:22.59 Kevin DeForrest, USA 0:22.59 Robin Leamy, USA 0:22.89 Rowdy Gaines, USA 1984 0:22.77 Jorg Woithe, GDR 0:22.83 Mark Stockwell, AUS 0:22.87 Peng-Siong Ang, SIN 1985 0:22.40 Tom Jager, USA 0:22.52 Dano Halsall, SUI 0:22.65 Matt Biondi, USA 1986 0:22.32 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.49 Tom Jager, USA 0:22.62 Stefan Volery, SUI 1987 0:22.32 Tom Jager, USA 0:22.33 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.47 Jorg Woithe, GDR 1988 0:22.14 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.18 Peter Williams, RSA 0:22.23 Tom Jager, USA 1989 0:22.12 Tom Jager, USA 0:22.36 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.47 Steve Crocker, USA 1990 0:21.81 Tom Jager, USA 0:21.85 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.41 Steve Crocker, USA 1991 0:22.14 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.16 Tom Jager, USA 0:22.32 Steve Crocker, USA 1992 0:21.91 Alexander Popov, RUS 0:22.09 Matt Biondi, USA 0:22.17 Tom Jager, USA 1993 0:22.24 Raimundas Mazuolis, LTU 0:22.27 Alexander Popov, RUS 0:22.30 David Fox, USA 1994 0:22.08 Raimundas Mazuolis, LTU 0:22.17 Alexander Popov, RUS 0:22.33 Tom Jager, USA 1995 0:22.23 David Fox, USA 0:22.25 Tamer Zeruhn, EGY 0:22.25 Alexander Popov, RUS 1996 0:22.13 Alexander Popov, RUS 0:22.26 Gary Hall, USA 0:22.29 Fernando Scherer, BRA 1997 0:22.30 Alexander -

Mistrzostwa Europy

Mistrzostwa Europy Historia Mistrzostwa Europy – Historia Medale Polaków 47 medali (16 złotych – 13 srebrnych – 18 brązowych) Kobiety: 20 medali (5 złotych – 5 srebrnych – 10 brązowych) Mężczyźni: 27 medali (11 złotych – 8 srebrnych – 8 brązowych) Najwięcej medali: Otylia Jędrzejczak (5 złotych – 3 srebrne – 2 brązowe) Najlepsze mistrzostwa: Budapeszt 2006 (5 złotych – 2 srebrne – 1 brązowy) Multimedaliści: Miejsce Imię i nazwisko Złoto Srebro Brąz Razem 1. Otylia Jędrzejczak 5 3 2 10 2. Paweł Korzeniowski 3 - - 3 3. Rafał Szukała 2 2 1 5 4. Artur Wojdat 2 2 - 4 5. Bartosz Kizierowski 2 - 2 4 6. Alicja Pęczak - 1 3 4 7. Katarzyna Baranowska - 1 1 2 8. Agnieszka Czopek - - 2 2 8. Mariusz Podkościelny - - 2 2 8. Mariusz Siembida - - 2 2 Konkurencje przynoszące medale: Miejsce Imię i nazwisko Złoto Srebro Brąz Razem 1. 200 m stylem motylkowym 7 3 2 12 2. 100 m stylem motylkowym 2 2 3 7 3. 200 m stylem dowolnym 2 1 - 3 4. 50 m stylem dowolnym 2 - - 2 5. 200 m stylem klasycznym 1 2 3 6 6. 400 m stylem dowolnym 1 1 1 3 7. 200 m stylem grzbietowym 1 - - 1 8. 400 m stylem zmiennym - 2 3 5 9. 200 m stylem zmiennym - 1 1 2 10. 4x200 m stylem dowolnym - 1 - 1 11. 50 m stylem grzbietowym - - 2 2 11. 1500 m stylem dowolnym - - 2 2 13. 4x100 m stylem zmiennym - - 1 1 Mistrzostwa Europy – Historia Medale Polaków Turyn 1954 srebro (1): Marek Petrusewicz 200 m stylem klasycznym 2:42.5 Split 1981 srebro (1): Leszek Górski 400 m stylem zmiennym 4:23.62 brąz (3): Grażyna Dziedzic 200 m stylem klasycznym 2:35.35 Agnieszka Czopek 200 m stylem motylkowym 2:13.57 -

2015 WMA Outdoor Championships Lyon Results M35 100 Meter Dash ===

WMA Championship Meet Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 11:59 AM 17/08/2015 Page 1 2015 WMA Outdoor Championships Lyon Results M35 100 Meter Dash ======================================================================== WMA: # 9.97 Name Age Team Prelims Wind H# ======================================================================== Preliminaries 1 Melfort, Jimmy M36 France 10.89Q -2.7 1 2 Beitia, Orkatz M36 Spain 11.01Q -1.4 3 3 Ridley, Babatunde M37 United State 11.09Q -0.8 2 4 Martinez, Lion M37 Sweden 11.11Q -0.8 7 5 Gippert, Jochen M38 Germany 11.15Q -0.6 4 6 Fernandez, Alberto M37 Spain 11.15Q -1.8 6 7 Viallet, Michel M35 France 11.25Q -2.5 9 8 Torres, Jassiel M38 Puerto Rico 11.26Q +0.0 11 9 Rahoui, Imad M35 France 11.36Q -1.3 5 10 Niangane, Samba M39 France 11.45Q -2.4 10 11 Phelan, Leigh M39 Australia 11.46Q -0.4 8 12 Lucenay, Steeve M39 France 11.13q -1.4 3 13 Zaitcev, Ivan M38 Russia 11.24q -1.8 6 14 Owen, Ben M35 Great Britai 11.24q -2.7 1 15 Clark, Dedrick M36 United State 11.32q +0.0 11 16 Beaumont, David M36 France 11.34q -0.8 2 17 Arlanda, Michel M35 France 11.34q -2.5 9 18 Channon, Stuart M38 Great Britai 11.41q -0.8 7 19 Saraceno, Francesco M36 Italy 11.44q +0.0 11 20 Lazazzera, Claudio M37 Switzerland 11.50q -0.8 2 21 Edwards, Marvin M35 Great Britai 11.54q -1.3 5 22 Portoles, Javier M39 Spain 11.58q -2.4 10 23 Schuetz, Stephan M36 Switzerland 11.62q -0.4 8 24 Bayard, Jean-Christophe M36 Belgium 11.63q -1.3 5 25 Bogaert, Sam M35 Belgium 11.70 -2.5 9 26 Vázquez, Yankar M38 Puerto Rico 11.70 -1.4 3 27 Paul, Patrice M36 France 11.73 -

Dossier Complet

Objectifs A MI-CHEMIN DE PEKIN ! C’est une délégation française composée au total de 55 athlètes que nous aurons le plaisir de voir participer aux Championnats d’Europe 2006. A deux ans des jeux Olym- piques de Pékin, le Président de la Fédération, Francis Luyce et son Directeur Techni- que National, Claude Fauquet fondent de grands espoirs sur cette équipe de France. Christine Caron (Vice-championne Olympique du 100 m dos aux JO de Tokyo en 1964) présente à Budapest en sa qualité de marraine de l’Equipe de France sera accompagnée, à partir du lundi 31 juillet, par un autre grand nom de la natation fran- çaise, l’ancien recordman du monde du 100 nage libre en 1964, Alain Gottvalles. La natation en Eau libre sera la première, avec la natation Synchronisée, à débuter la compétition (du mercredi 26 au dimanche 30 juillet). Viendront ensuite, la natation Course (lundi 31 juillet au dimanche 6 août) et le Plongeon (mardi 1er au dimanche 6 août). Eau libre : Les championnats d’Europe 2006 permettront de mesurer les premiers effets de cette nouvelle discipline Olympique sur l’épreuve du 10 km. En sélectionnant neuf nageurs après les championnats de France Indoor du 5 km à Strasbourg et les championnats de France à Mimizan, l’objectif de la DTN est de faire le point, à l’issue de Budapest, sur les potentiels Olympiques. L’équipe de France, composée de 3 filles et 6 garçons, va évoluer dans un contexte plus relevé que d’habitude. Néanmoins, le soutien des leaders de l’Eau libre fran- çaise, Stéphane Gomez et Gilles Rondy, dont la solide expérience sur le terrain inter- national n’est plus à prouver, est un vrai atout pour cette jeune équipe. -

Time Swimmer Country Venue Length of Pool Date Men: (50 M Unless

Length of Time Swimmer Country Venue pool Date Men: (50 m unless stated) 50 metres freestyle 22.7 Standard time 22.52 Dano Halsall (SUI) Bellinzona 21-07-1985 22.47 Jorg Woithe (GDR) Munich 28-08-1987 22.33 Nils Rudolph (GER) Athens 24-08-1991 22.31 Alexander Popov (CSI) Canet 30-05-1992 22.21 Alexander Popov (CSI) Barcelona 30-07-1992 21.91 Alexander Popov (CSI) Barcelona 30-07-1992 21.64 Alexander Popov (RUS) Moscow 16-06-2000 21.50 Alain Bernard (FRA) Eindhoven 23-03-2008 21.38 Amaury Leveaux (FRA) Dunkerque 26-04-2008 20.94 Frederick Bousquet (FRA) Montpellier 26-04-2009 100 metres freestyle 60.0 Arne Borg (SWE) Bologna 04-09-1927 59.8 Istvan Barany (HUN) Amsterdam 11-08-1928 58.6 Istvan Barany (HUN) Munich 25m 29-10-1929 58.4 Istvan Barany (HUN) Budapest 33m 12-05-1931 57.8 Ferenc Csik (HUN) Budapest 20-08-1935 56.8 Helmuth Fischer (GER) Berlin 25m 26-04-1936 56.7 Alex Jany (FRA) Marseille 25m 12-06-1946 56.6 Alex Jany (FRA) Marseille 25m 18-09-1946 56.2 Alex Jany (FRA) Monte Carlo 10-09-1947 55.8 Alex Jany (FRA) Menton 25m 15-09-1947 New regulations- records in 50m/55 y pools only recognised 56.1 Paolo Pucci (ITA) Budapest 31-08-1955 55.8 Gyula Dobai (HUN) Budapest 31-07-1960 55.7 Gyula Dobai (HUN)) Budapest 18-09-1960 55.5 Per Ola Lindberg (SWE) Halmstad 09-08-1961 55.0 Alain Gottvalles (FRA) Thionville 10-08-1962 54.4 Bobby McGregor (GBR) Blackpool 55y 13-07-1963 54.3 Per Ola Lindberg (SWE) Baastad 18-07-1963 54.1 Bobby McGregor (GBR) Blackpool 55y 31-08-1963 54.0 Bobby McGregor (GBR) Blackpool 55y 13-09-1963 53.9 Bobby McGregor