Echo Park Vs. Hollywood in Allison Anders's Mi Vida Loca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Six Projects Selected for 2013 Rawi Screenwriters Lab in Jordan

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: November 1, 2013 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] Six Projects Selected for 2013 Rawi Screenwriters Lab in Jordan Led By The Royal Film Commission-Jordan in Consultation with Sundance Institute, Lab Supports Emerging Filmmakers in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine Los Angeles, CA — Screenwriting fellows for the ninth edition of the Rawi Screenwriters Lab (November 1-5) were announced today by The Royal Film Commission-Jordan and Sundance Institute. The Lab is an example of Sundance Institute’s longstanding work to support emerging filmmakers around the world. Former Rawi Fellows include Cherien Dabis (Amreeka), Mohammed Al Daradji (Son of Babylon), Sally El Hosaini (My Brother The Devil) and Haifaa Al Mansour (Wadjda). Launched in 2005, the Lab is led by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan (RFC) and managed by Deema Azar, in consultation with Sundance Institute’s Feature Film Program, under the direction of Michelle Satter. The Lab provides an opportunity for filmmakers from the region to develop their work under the guidance of accomplished Creative Advisors—this year including Jeremy Pikser (Bulworth), Najwa Najjar (Pomegranates & Myrrh), Mo Ogrodnick (Deep Powder). Aseel Mansour (Line Of Sight), Rose Troche (The L Word, The Safety Of Objects) and Jerome Boivin (La cloche a sonné)—in an environment that encourages storytelling at the highest level. George David, General Manager of the RFC, said, “For the ninth consecutive year, RAWI continues to unveil the regions’ exceptional talent and narratives as part of the RFC’s goal to champion a new generation of Arab film professionals who will represent our noble culture and values, our triumphs and struggles and our hopes and dreams through their films.” Paul Federbush, International Director of the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program, said, “We’ve had the privilege to help give voice to some extraordinary new filmmakers in the region over our nine-year partnership with the RFC. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Commercial Films/Video Tapes on Teaching

Commercial Films/Video Tapes On Teaching Prepared by Gary D Fenstermacher Three categories of film or video are included here, depending on whether teaching occurs in the setting of a school (Category I), in a tutorial relationship between teacher and student (Category II), or simply as a plot device in a comedy about or parody of teaching and schooling (Category III). Films described in Category I are listed alphabetically, within decade headings; it is the year the film was made, not the time period it depicts, that determines the decade in which the film is classified. Category I: Depicting Teachers in School Settings 1930's Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939). Robert Donat, Greer Garson. British schoolmaster devoted to "his boys." Remade as musical in 1969, starring Peter O'Toole; remake received poor reviews. If you select this film, please do not use the remade version; use the original, 1939, film. It is a first-rate film. 1940's The Corn is Green (1945). Bette Davis, Nigel Bruce. Devoted teacher copes with prize pupil in Welsh mining town in 1895. (1 hr 35 min) Highly regarded remake in 1979 stars Katherine Hepburn in her last teaming with director George Cukor. OK to use either version (1945 or 1979). 1950's Blackboard Jungle (1955). Glenn Ford, Anne Francis. Teacher's difficult adjustment to New York City schools. First commercial film to feature rock music. 1960's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969). Maggie Smith. Eccentric teacher in British girls school. Smith wins Oscar for her performance. Remade as TV miniseries. To Sir With Love (1967, British). -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 32 Issue 2 Theater and Performance in Nuestra Article 12 América 6-1-2008 Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity Nohemy Solózano-Thompson Whitman College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Solózano-Thompson, Nohemy (2008) "Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 32: Iss. 2, Article 12. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/2334-4415.1686 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity Abstract This paper analyzes how Culture Clash problematizes Chicano masculinity through the manipulation of two iconic Chicano characters originally popularized by two films starring dwarE d James Olmos - the pachuco from Luis Valdez’s Zoot Suit (1981) and the portrayal of real-life math teacher Jaime Escalante in Stand and Deliver (1988). In “Stand and Deliver Pizza” (from A Bowl of Beings, 1992), Culture Clash tries to introduce new Chicano characters that can be read as masculine, and who at the same time, display alternative behaviors and characteristics, including homosexual desire. The three characters in “Stand and Deliver Pizza” represent stock icons of Chicano masculinity. -

RAYMOND PRADO 2Nd UNIT DIRECTOR DGA

RAYMOND PRADO 2nd UNIT DIRECTOR DGA www.raymondprado.com SECOND UNIT DIRECTOR DANGEROUS LIAISONS (Pilot) 3 Arts / ABC Prod: Wren Arthur, Richard LaGravenese, Erwin Stoff, Dir: Taylor Hackford Ilene Staple, Margot Lulick COMPANY TOWN (Pilot) CBS Studios/The CW Prod: Jeff Hayes, Bill Haber Dir: Taylor Hackford SOURCE CODE Summit Prod: Mark Gordon, Jordan Wynn, Hawk Koch Dir: Duncan Jones PARKER Incentive Filmed Ent. Prod: Taylor Hackford, Steve Chasman, Dir: Taylor Hackford Les Alexander THE PROPOSAL Touchstone Prod: Todd Lieberman, David Hoberman, Dir: Anne Fletcher Mary McLaglen LOVE RANCH E1 Entertainment Prod: Taylor Hackford, Lou DiBella, Marty Katz Dir: Taylor Hackford RAY Universal Pictures Prod: Taylor Hackford, Stuart Benjamin, Dir: Taylor Hackford Howard Baldwin, Karen Baldwin E-RING (Pilot) Warner Bros. TV/NBC Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer, David McKenna Dir: Taylor Hackford NUMB3RS (Pilot) Paramount Network TV/CBS Prod: Nicolas Falacci, Cheryl Heuton, Dir: Gregor Jordan Tony Scott, Ridley Scott DODGEBALL 20th Century Fox Prod: Stuart Cornfeld, Ben Stiller, Mary McLaglen Dir: Rawson Marshall Thurber TWO WEEK’S NOTICE Warner Bros. Pictures Prod: Sandra Bullock, Mary McLaglen Dir: Marc Lawrence MISS CONGENIALITY Warner Bros. Pictures Prod: Sandra Bullock, Marc Lawrence Dir: Donald Petrie GUN SHY Hollywood Pictures Prod: Sandra Bullock, Marc S. Fischer Dir: Eric Blakeney STORYBOARDS/CONCEPTS WEST SIDE STORY 20th Century Fox Prod: Rita Moreno, Kevin McCollum, Kristie Krieger Dir: Steven Spielberg VICE Annapurna Productions Prod: Will Ferrell, -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

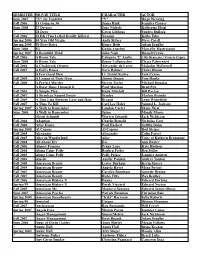

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter