A Look at the Historical Conversation Between Hip-Hop and Christianity" (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff About ANF01

ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff About ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff Title: ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.html Author(s): Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: The Ante-Nicene Christian library is meant to comprise translations into English of all the extant works of the Fathers down to the date of the first General Council held at Nice in A.D. 325. The sole provisional exception is that of the more bulky writings of Origen. It is intended at present only to embrace in the scheme the Contra Celsum and the De Principiis of that voluminous author; but the whole of his works will be included should the undertaking prove successful. Publication History: Text edited by Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson and first published in Edinburgh, 1867. Additional introductionary material and notes provided for the American edition by A. Cleveland Coxe 1886. Print Basis: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, reprint 2001 Source: Logos Research Systems, Inc. Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2002-10 Status: Proof reading, ThML markup and subject index for Version 3.0 by Timothy Lanfear General Comments: Hebrew and Greek were checked against page scans of the 1995 Hendrickson reprint by SLK; errors in the hard copy have not been corrected in this digitized text. Contributor(s): Timothy Lanfear (Markup) CCEL Subjects: All; Early Church; Classic; Proofed; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. -

Losing My Voice 1P.Indd 3 6/14/19 12:50 PM Losing My Voice 1P.Indd 4 6/14/19 12:50 PM Losing My Voice to Find It MARK STUART STORY

losing my voice to find it Losing My Voice_1P.indd 3 6/14/19 12:50 PM Losing My Voice_1P.indd 4 6/14/19 12:50 PM losing my voice to find it MARK STUART STORY MARK STUART Losing My Voice_1P.indd 5 6/14/19 12:50 PM © 2019 Mark Stuart All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other— except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Nelson Books, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Nelson Books and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc. Thomas Nelson titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund- raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e- mail [email protected]. Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.Zondervan.com. The “NIV” and “New International Version” are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.® Any Internet addresses, phone numbers, or company or product information printed in this book are offered as a resource and are not intended in any way to be or to imply an endorsement by Thomas Nelson, nor does Thomas Nelson vouch for the existence, content, or services of these sites, phone numbers, companies, or products beyond the life of this book. -

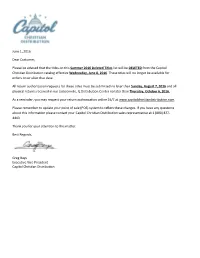

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please Be Advised That the Titles On

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please be advised that the titles on this Summer 2016 Deleted Titles list will be DELETED from the Capitol Christian Distribution catalog effective Wednesday, June 8, 2016. These titles will no longer be available for orders on or after that date. All return authorization requests for these titles must be submitted no later than Sunday, August 7, 2016 and all physical returns received in our Jacksonville, IL Distribution Center no later than Thursday, October 6, 2016. As a reminder, you may request your return authorization online 24/7 at www.capitolchristiandistribution.com. Please remember to update your point of sale (POS) system to reflect these changes. If you have any questions about this information please contact your Capitol Christian Distribution sales representative at 1 (800) 877- 4443. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Best Regards, Greg Bays Executive Vice President Capitol Christian Distribution CAPITOL CHRISTIAN DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2016 DELETED TITLES LIST Return Authorization Due Date August 7, 2016 • Physical Returns Due Date October 6, 2016 RECORDED MUSIC ARTIST TITLE UPC LABEL CONFIG Amy Grant Amy Grant 094639678525 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant My Father's Eyes 094639678624 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Never Alone 094639678723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Straight Ahead 094639679225 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Unguarded 094639679324 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant House Of Love 094639679829 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Behind The Eyes 094639680023 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant A Christmas To Remember 094639680122 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Simple Things 094639735723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Icon 5099973589624 Amy Grant Productions CD Seventh Day Slumber Finally Awake 094635270525 BEC Recordings CD Manafest Glory 094637094129 BEC Recordings CD KJ-52 The Yearbook 094637829523 BEC Recordings CD Hawk Nelson Hawk Nelson Is My Friend 094639418527 BEC Recordings CD The O.C. -

Detta Är En Dokumentmall För Examensarbeten

EXAMENSARBETE Höstterminen 2009 Lärarutbildningen i musik Elisabet Johansson Vilken roll spelar pianot i countrymusiken? En undersökning riktad till pianister, pianopedagoger och klasslärare i musik Handledare: Astrid Boström och Ulrika Bohlin Förord Jag vill börja med att tacka min informant för att han så generöst delat med sig av sina egna erfarenheter och sin kunskap. Jag vill även tacka familj, vänner och kurskamrater för tjänstvil- lighet och stöd. Slutligen vill jag tacka mina handledare Astrid Boström och Ulrika Bohlin för er hjälp och era tydliga direktiv genom hela processen. Studien har varit mycket givande och innehållit både glada och mindre glada stunder. Jag är mycket glad och stolt över att arbetet blivit klart och är övertygad om att arbetet kan ge både mig och andra musikpedagoger tips och hjälp i undervisningen framöver. Abstract Title: What part does the piano play in country music? – A study intended for pianists, piano pedagogues and class teachers in music Author: Elisabet Johansson The purpose of this essay is to find out what part the piano play in country music. The re- search includes an interview with an artist from Texas and an analysis of five chosen music examples. The research question is: What part does the piano play in country music and how can that knowledge influence my teaching as a piano pedagogue and class teacher in music? Four result areas appear and they are Piano as a rhythmic instrument, Piano as a lead-instrument, The piano’s interaction with the singer and The influences of the piano from other genres. The study concludes that there are different parts for the piano in country music. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Chance the Rapper Coloring Book Mp3, Flac, Wma

Chance The Rapper Coloring Book mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Coloring Book Country: US Released: 2016 MP3 version RAR size: 1582 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1475 mb WMA version RAR size: 1170 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 177 Other Formats: XM ADX MPC AC3 VQF ASF DMF Tracklist Hide Credits All We Got 1 Featuring – Chicago Children's Choir, Kanye WestProducer [Uncredited] – Kanye West, The 3:23 Social Experiment No Problem 2 5:04 Featuring – 2 Chainz, Lil WayneProducer [Uncredited] – Brasstracks Summer Friends 3 4:50 Featuring – Francis & The Lights*, Jeremih D.R.A.M. Sings Special 4 1:41 Featuring [Uncredited] – D.R.A.M. 5 Blessings 3:41 6 Same Drugs 4:17 Mixtape 7 4:52 Featuring – Lil Yachty, Young Thug Angels 8 3:26 Featuring – Saba Juke Jam 9 3:39 Featuring – Justin Bieber, Towkio All Night 10 2:21 Featuring – Knox Fortune How Great 11 5:37 Featuring – Jay Electronica, My Cousin Nicole Smoke Break 12 3:46 Featuring – Future Finish Line / Drown 13 6:46 Featuring – Eryn Allen Kane, Kirk Franklin, Noname , T-Pain Blessings (Reprise) 14 3:50 Featuring – Ty Dolla $ign* Credits Artwork [Uncredited] – Brandon Breaux Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Not On Label (Chance Chance The Coloring Book (14xFile, none The Rapper Self- none US 2016 Rapper MP3, Mixtape, 320) released) Coloring Book (2xLP, Chance The Not On Label (Chance CTRCB 3 Album, Mixtape, CTRCB 3 2016 Rapper The Rapper) Unofficial, Yel) Coloring Book (2xLP, Chance The Not On Label (Chance CTRCB3 Album, Mixtape, CTRCB3 2016 Rapper The Rapper) Unofficial, Cle) Chance The Coloring Book (2xLP, Not On Label (Chance none none UK 2018 Rapper Mixtape, Red) The Rapper) Coloring Book (2xLP, Chance The Not On Label (Chance none Mixtape, Unofficial, none US 2016 Rapper The Rapper) Gre) Related Music albums to Coloring Book by Chance The Rapper Rick Ro$$ - The Black Bar Mitzvah DJ UE - Monthly Whizz Vol. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

Blood Bought Radio Worldwide Report Dates from 8/30/2020 - 9/5/2020

BROADCASTER RAW DATA DRT SUMMARY REPORT BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO WORLDWIDE REPORT DATES FROM 8/30/2020 - 9/5/2020 ARTIST SONG TITLE LABEL TOTAL SPINS BRIDGING THE GAP VISIT TODAY AT MOVEMENT LLC WWWBRIDGINGTHGAPMOVEMENTLLCCOM UNKNOWN 64 BLOOD BOUGHT PRODUCTIONSWHERE SCHEDULE AN APPOINTMENT TODAY AT HARMONY MEETS QUALITY WWWBRIDGINGTHEGAPMOVEMENTLLC UNKNOWN 61 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR INTRO 1 UNKNOWN 59 TUNE INTO THE OFFICIAL STATION 4 CHH X RHYTHM BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO & PRAISE UNKNOWN 49 TUNE INTO WORD OF KNOWEDGE RADIO SHOW BRIDGING THE GAP EVERY SUNDAY AT 6PM EST ON BLOOD BOUGHT MOVEMEMENT LLC RADIO UNKNOWN 42 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR INTRO 2 UNKNOWN 40 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 6 UNKNOWN 25 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR THROWBACK INTRO 2 UNKNOWN 25 CLEAR VISION IMAGING SCHEDULE AN APPOINTMENT TODAY AT & MEDIA WWWBRIDGINGTHEGAPMOVEMENTLLC UNKNOWN 24 D ROAD BBR HIS HOP RADIO SHOW PROMO UNKNOWN 23 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 10 UNKNOWN 22 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 4 UNKNOWN 22 HOSTED BY @KNOWTHELEDGE415 X@MOSESBOYMUSIC - WORD OF KNOWLEDGE RADIO SHOW (2020 S8 EP19) UNKNOWN 21 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 3 UNKNOWN 20 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 2 UNKNOWN 19 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 5 UNKNOWN 19 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 9 UNKNOWN 19 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 1 UNKNOWN 18 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 7 UNKNOWN 18 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR PROMO 8 UNKNOWN 18 2ND SAMUEL 151 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO DROP UNKNOWN 11 KEYA SMITH BBR DROP UNKNOWN 11 DR HOWARD ROBERTS BBR DROP DO YOURSELF A FAVOR AND KEEP IT LOCKED UNKNOWN 9 BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO BBR -

Abstract Jordan III, Augustus W. B.S. Florida A&M University, 1994 A

Abstract Jordan III, Augustus W. B.S. Florida A&M University, 1994 A Study of Language and Ideology in Rap Music Advisor: Dr. O. Osinubi Dissertation Dated June 5,1998 This study examined the language of Hip-Hop songs and ideology of the artists as reflected through their songs. The study was based on the theory that Hip-Hop or rap songs are legitimate artforms because of their use of poetic elements such as figuration, figures of sound, symbolism, and ambiguity. The study recorded and interpreted the lyrics of a few current rap songs for the purpose of investigating their poetical and ideological elements. The researcher found signification battles by some rap artists as the best examples of songs which express the richness and complexity of Hip-Hop music. The researcher found that both Hip-Hop music lyrics and standard poetry have many similarities, but also have a few different features which enhance their uniqueness. The conclusions drawn from the findings suggest that the main reason many critics do not consider Hip-Hop or rap music an artform, is that they either compare the music to something extremely different, or they simply do not take the time to listen to its songs. Rap Music is an artform that expresses poetic elements and utilizes electronic devices, thus making it a Postmodernist popular artform. Through the research, the researcher showed that rap music lyrics also have intense meaning, just like poetry. 2 A STUDY OF LANGUAGE AND IDEOLOGY IN RAP MUSIC A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AFRICAN AND AFRICAN-AMERICAN STUDIES BY AUGUSTUS JORDAN III SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ATLANTA,GA JULY 1998 R -111 P-Jfl © 1998 AUGUSTUS W. -

Jay Brown Rihanna, Lil Mo, Tweet, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J ISLAND/DEF JAM, 825 8Th Ave 28Th Floor, NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 333 8000 / Fax +1 212 333 7255

Jay Brown Rihanna, Lil Mo, Tweet, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J ISLAND/DEF JAM, 825 8th Ave 28th Floor, NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 333 8000 / Fax +1 212 333 7255 14. Jerome Foster a.k.a. Knobody Akon STREET RECORDS CORPORATION, 1755 Broadway 6th , NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 331 2628 / Fax +1 212 331 2620 16. Rob Walker Clipse, N.E.R.D, Kelis, Robin Thicke STAR TRAK ENTERTAINMENT, 1755 Broadway , NY 10019 New York, USA Phone +1 212 841 8040 / Fax +1 212 841 8099 Ken Bailey A&R Urban Breakthrough credits: Chingy DISTURBING THA PEACE 1867 7th Avenue Suite 4C NY 10026 New York USA tel +1 404 351 7387 fax +1 212 665 5197 William Engram A&R Urban Breakthrough credits: Bobby Valentino Chingy DISTURBING THA PEACE 1867 7th Avenue Suite 4C NY 10026 New York USA tel +1 404 351 7387 fax +1 212 665 5197 Ron Fair President, A&R Pop / Rock / Urban Accepts only solicited material Breakthrough credits: The Calling Christina Aguilera Keyshia Cole Lit Pussycat Dolls Vanessa Carlton Other credits: Mya Vanessa Carlton Current artists: Black Eyed Peas Keyshia Cole Pussycat Dolls Sheryl Crow A&M RECORDS 2220 Colorado Avenue Suite 1230 CA 90404 Santa Monica USA tel +1 310 865 1000 fax +1 310 865 6270 Marcus Heisser A&R Urban Accepts unsolicited material Breakthrough credits: G-Unit Lloyd Banks Tony Yayo Young Buck Current artists: 50 Cent G-Unit Lloyd Banks Mobb Depp Tony Yayo Young Buck INTERSCOPE RECORDS 2220 Colorado Avenue CA 90404 Santa Monica USA tel +1 310 865 1000 fax +1 310 865 7908 www.interscope.com Record Company A&R Teresa La Barbera-Whites -

Dj Whoo Jae Millz Dj Vlad

BACK 2 SCHOOL FASHIONS MIXTAPE REVIEWS COLLECTOR’S EDITION Re-Defining The Mixtape Game DJ WHOO KIDG-UNIT’S GENERAL ADDS $TREET VALUE TO THE GAME JAE MILLZ PLUS: POPS OFF A CONRAD DIMANCHE XAVIER AEON MILLION ROUNDS HAWK VOLUME 1 ISSUE 2 DJ VLAD THE BUTCHER CUTS IT UP >DJ WHOO KID On the cover and this page: (“Street Value” Pg. 44) Photographed Exclusively for Mixtape Magazine by RON WEXLER FEATURES CONTENT VOL.1 ISSUE 2 44 DJ WHOO KID $TREET VALUE G-Unit General or G-Unit Soldier? Crown the kid king if you call him anything. DJ Whoo Kid in his most upfront story to date alerts the game about his strategy and formula for worldwide, not just domestic success. By Kay Konnect 70 Xavier Aeon 74 DJ VLAD 80 Jae Millz THE BUTCHER Rhythm and Blues new Mix it up. Blend it up. Jae Millz, the lyrical sharp- boy wonder from the CT, Whatever you do, make shooter steps to the streets Connecticut to be exact, sure to cut it up. DJ Vlad in a Mixtape Magazine explains in an uncut manner “The Butcher” slices the exclusive. He drops bullets the difference between a mixtape game in half with regarding his demeanor and typical artist and one with exclusive compilations from operation in the mixtape rap an edge. Shaken with a the east-south-mid-west. world. Ready as ever, Jae Hip Hop feel, Xavier Aeon DJ Vlad’s story plugs the Millz pops off a million exposes his sharpness. world to his sword-like rounds easily. -

Race, Technology, and Theology in the Emergence of Christian Rap Music

Pneuma 33 (2011) 200-217 brill.nl/pneu “It’s Not the Beat, but It’s the Word that Sets the People Free”: Race, Technology, and Theology in the Emergence of Christian Rap Music Josef Sorett Assistant Professor of Religion and African-American Studies, Columbia University, New York [email protected] Abstract In an effort to address lacunae in the literature on hip hop, as well as to explore the role of new music and media in Pentecostal traditions, this essay examines rap music within the narra- tives of American religious history. Specifically, through an engagement with the life, ministry, and music of Stephen Wiley — who recorded the first commercially-released Christian rap song in 1985 — this essay offers an account of hip hop as a window into the intersections of religion, race, and media near the end of the twentieth century. It shows that the cultural and theological traditions of Pentecostalism were central to Wiley’s understanding of the significance of racial ideology and technology in his rap ministry. Additionally, Wiley’s story helps to iden- tify a theological, cultural, and technological terrain that is shared, if contested, by mainline Protestant, neo-Pentecostal, and Word of Faith Christians during a historical moment that has been described as post-denominational. Keywords Christian hip hop, Stephen Wiley, Word of Faith, racial ideology Over the past two decades a growing body of research on hip hop music and culture has taken shape. More often than not, the inquiries in this emerging literature have located hip hop (or rap) in the traditions of African American cultural (literary and musical) expression.1 Within this corpus, little attention 1 The two seminal works in the field of hip hop studies are Tricia Rose’sBlack Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Press, 1993); Houston Baker’s Black Studies, Rap, and the Academy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).