2010 FIFA World Cup Stadium Investment: Does the Post-Event Usage Justify the Expenditure?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As a Child You Have No Way of Knowing How Fast Or Otherwise The

A FOREIGN COUNTRY: GROWING UP IN RHODESIA Nigel Suckling Draft: © January 2021 1 I – MUNALI – 5 II – LIVINGSTONE – 43 III – PARALLEL LIVES – 126 IV – LUSAKA – 212 V – GOING HOME – 244 APPENDIX – 268 2 FOREWORD As a child you have no measure of how fast the world around you is changing. Because you’re developing so quickly yourself, you assume your environment is static and will carry on pretty much the same as you grow into it. This is true for everyone everywhere, naturally. Most old people can, if suitably primed, talk indefinitely about the changes they’ve seen in their lifetimes, even if they’ve never moved from the place where they were born; but some environments change more drastically than others, even without a war to spur things along. One such was Northern Rhodesia in southern Africa in the 1950s and 60s. As white kids growing up then we had no way of knowing, as our parents almost certainly did, just how fragile and transient our conditions were – how soon and how thoroughly the country would become Zambia, with a completely different social order and set of faces in command. The country of course is still there. In many ways its urban centres now look remarkably unchanged due to relative poverty. The houses we grew up in, many of the streets, landmark buildings and landscapes we were familiar with are still recognizably the same, much more so in fact than in many parts of Europe. What has vanished is the web of British colonial superstructure into which I and my siblings were born as privileged members, brief gentry on the cusp of a perfectly justified and largely peaceful revolution that was soon to brush us aside. -

A Room with a View Cape Town Hotels and Tourism

A room with a view Cape Town hotels and tourism Publication jointly compiled by Wesgro, City of Cape Town and PwC September 2014 ©Cape Town Tourism ©Cape Town Tourism Contents Foreword by the Executive Mayor of Cape Town 1 Message by the CEO of Wesgro 3 Message by the Partner in Charge, PwC Western Cape 3 Contacts 4 Western Cape tourism in numbers 6 Our research 8 Section 1: Unpacking the Cape Town tourism sector 10 Foreign tourist arrivals 13 Bed nights spent by foreign tourists 18 Foreign direct investment in the Cape Town hotel industry 18 Recent hotel transactions 19 Average length of stay by province 19 Total foreign direct spend 19 Business tourism 20 Q&A with... 22 Enver Duminy – CEO, Cape Town Tourism Q&A with... 26 Alayne Reesberg – CEO, Cape Town Design, the implementing agency for Cape Town World Design Capital 2014 Q&A with... 28 Michael Tollman – CEO, Cullinan Holdings 2 A room with a view September 2014 Section 2: Hotel accommodation 30 Overview 32 Defining ‘hotel’ 32 Significant themes 32 Governance in the hotel industry 33 Cape Town hotels – STR statistics 34 Occupancy 34 Average daily room rate and revenue per available room (RevPAR) 35 Supply and demand 36 Q&A with... 38 John van Rooyen – Operations Director, Tsogo Sun Cape Region Q&A with... 42 David Green – CEO, V&A Waterfront Q&A with... 46 Joop Demes – CEO, Pam Golding Hospitality and Kamil Abdul Karrim – Managing Director, Pam Golding Tourism & Hospitality Consulting Section 3: List of selected hotels in Cape Town 54 ©Cape Town Tourism 4 A room with a view Photo: The Clock Tower at the September V&A Waterfront 2014 Foreword by the Executive Mayor of Cape Town The City of Cape Town is privileged to be part of this strategic publication for the hospitality industry in Cape Town. -

Vigilantism V. the State: a Case Study of the Rise and Fall of Pagad, 1996–2000

Vigilantism v. the State: A case study of the rise and fall of Pagad, 1996–2000 Keith Gottschalk ISS Paper 99 • February 2005 Price: R10.00 INTRODUCTION South African Local and Long-Distance Taxi Associa- Non-governmental armed organisations tion (SALDTA) and the Letlhabile Taxi Organisation admitted that they are among the rivals who hire hit To contextualise Pagad, it is essential to reflect on the squads to kill commuters and their competitors’ taxi scale of other quasi-military clashes between armed bosses on such a scale that they need to negotiate groups and examine other contemporary vigilante amnesty for their hit squads before they can renounce organisations in South Africa. These phenomena such illegal activities.6 peaked during the1990s as the authority of white su- 7 premacy collapsed, while state transfor- Petrol-bombing minibuses and shooting 8 mation and the construction of new drivers were routine. In Cape Town, kill- democratic authorities and institutions Quasi-military ings started in 1993 when seven drivers 9 took a good decade to be consolidated. were shot. There, the rival taxi associa- clashes tions (Cape Amalgamated Taxi Associa- The first category of such armed group- between tion, Cata, and the Cape Organisation of ings is feuding between clans (‘faction Democratic Taxi Associations, Codeta), fighting’ in settler jargon). This results in armed groups both appointed a ‘top ten’ to negotiate escalating death tolls once the rural com- peaked in the with the bus company, and a ‘bottom ten’ batants illegally buy firearms. For de- as a hit squad. The police were able to cades, feuding in Msinga1 has resulted in 1990s as the secure triple life sentences plus 70 years thousands of displaced persons. -

Employment Equity Act: Public Register

STAATSKOERANT, 7 MAART 2014 No. 37426 3 CORRECTION NOTICE Extraordinary National Gazette No. 37405, Notice No. 146 of 7 March 2014 is hereby withdrawn and replaced with the following: Gazette No. 37426, Notice No. 168 of 7 March 2014. GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 168 OF 2014 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE EMPLOYMENT EQUITY ACT, 1998 (ACT NO. 55 OF 1998) I, Mildred Nelisiwe Oliphant, Minister of Labour, publish in the attached Schedule hereto the register maintained in terms of Section 41 of the Employment Equity Act, 1998 (Act No. 55 of 1998) of designated employers that have submitted employment equity reports in terms of Section 21, of the Employment Equity Act, Act No. 55 of 1998. 7X-4,i_L4- MN OLIPHANT MINISTER OF LABOUR vc/cgo7c/ t NOTICE 168 OF 2014 ISAZISO SASEREJISTRI SOLUNTU UMTHETHO WOKULUNGELELANISA INGQESHO, (UMTHETHO YINOMBOLO YAMA-55 KA-1998) Mna, Mildred Nelisiwe Oliphant, uMphathiswa wezabasebenzi, ndipapasha kule Shedyuli iqhakamshelwe apha irejista egcina ngokwemiqathango yeCandelo 41 lomThetho wokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, ka-1998 (umThetho oyiNombolo yama- 55 ka-1998)izikhundlazabaqeshi abangeniseiingxelozokuLungelelanisa iNgqeshongokwemigaqo yeCandelo 21, lomThethowokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka-1998. MN OLIPHANT UMPHATHISWA WEZEMISEBENZI oVe7,742c/g- This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 37426 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 7 MARCH 2014 List of designated employers who reported for the 01 September 2013 reporting cycle No: This represents sequential numbering of designated employers and bears no relation to an employer. (The list consists of 4984 large employers and 10182 small employers). Business name: This is the name of the designated employer who reported. Status code: 0 means no query. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

KO* HOME AWAY VENUE TOURNAMENT 03-Jun-11 19:10 Bulls

KO* HOME AWAY VENUE TOURNAMENT 03-Jun-11 19:10 Bulls 23-17 Waratahs Loftus Versfeld, Pretoria 03-Jun-11 19:35 Highlanders 14-21 Western Force Carisbrook, Dunedin 03-Jun-11 19:40 Rebels 3-40 Stormers Melbourne Rectangular Stadium 04-Jun-11 - RugbyRocks London 7s Winners: Samurai Barracudas Richmond, London 04-Jun-11 14:30 Italy A 12-26 Canada Franklin’s Gardens 04-Jun-11 14:30 Wales 28-31 Barbarians Millennium Stadium Estadio Libertadores de América, 04-Jun-11 16:10 Argentina 23-19 French Barbarians Buenos Aires 04-Jun-11 17:00 England Saxons 87-8 USA Franklin’s Gardens 04-Jun-11 17:05 Cheetahs 18-23 Sharks Free State Stadium, Bloemfontein 04-Jun-11 17:30 Hurricanes 38-27 Lions Westpac Stadium, Wellington 04-Jun-11 19:35 Blues 11-16 Chiefs Eden Park, Auckland 04-Jun-11 19:40 Reds 14-22 Brumbies Lang Park, Brisbane 04-Jun-11 21:00 FINAL: TOULOUSE 15-10 Montpellier Stade de France 08-Jun-11 17:30 USA 44-13 Tonga Moseley Road 08-Jun-11 20:00 Canada 34-18 Russia Moseley Road 10-Jun-11 19:35 Chiefs 18-18 Hurricanes Waikato Stadium, Hamilton 10-Jun-11 19:40 Brumbies 32-17 Rebels Canberra Stadium 11-Jun-11 16:05 Lions 30-30 Sharks Ellis Park, Johannesburg Estadio del Centenario Stadium, 11-Jun-11 16:10 Argentina 21-18 French Barbarians Resistencia 11-Jun-11 18:10 Stormers 16-19 Bulls Newlands Stadium, Cape Town 11-Jun-11 19:35 Crusaders 23-16 Blues Fraser Park, Timaru 11-Jun-11 19:40 Waratahs 33-7 Highlanders Sydney Football Stadium 11-Jun-11 20:05 Western Force 21-24 Reds Perth Oval 12-Jun-11 14:30 England Saxons 41-14 Tonga Kingsholm 12-Jun-11 -

The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J

University of Massachusetts School of Law Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts School of Law Faculty Publications 2016 The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J. Peltz-Steele University of Massachusetts School of Law - Dartmouth, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umassd.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard J. Peltz-Steele, The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between (Sept 27, 2016) (unpublished paper). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard Peltz-Steele Abstract With Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022 on the horizon, the process for selecting hosts for the World Cup of men’s football has been plagued by charges of corruption and human rights abuses. FIFA celebrated key developing economies with South Africa 2010 and Brazil 2014. But amid the aftermath of the global financial crisis, those sitings surfaced grave and persistent criticism of the social and economic efficacy of sporting mega-events. Meanwhile new norms emerged in global governance, embodied in instruments such as the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and the Sustainable Development Goals. These norms posit that commercial aims can be harmonized with socioeconomic good. FIFA seized on the chance to restore public confidence and recommit itself to human exultation in sport, adopting sustainability strategies and engaging the architect of the UNGP to develop a human rights policy. -

No. DATE HOST VERSUS STADIUM PROVINCE 1. 1994.04.24 South

No. DATE HOST VERSUS STADIUM PROVINCE 1. 1994.04.24 South Africa Zimbabwe Mmabatho Stadium North West 2. 1994.05.10 South Africa Zambia Ellis Park Gauteng 3. 1994.11.26 South Africa Ghana Loftus Versfeld Gauteng 4. 1994.11.30 South Africa Cote d'Ivoire Boet Erasmus Stadium Eastern Cape 5. 1994.12.03 South Africa Cameroon Ellis Park Gauteng 6. 1995.05.13 South Africa Argentina Ellis Park Gauteng 7. 1995.09.30 South Africa Mozambique Soccer City Gauteng 8. 1995.11.22 South Africa Zambia Loftus Versfeld Gauteng 9. 1995.11.26 South Africa Zimbabwe Soccer City Gauteng 10. 1995.11.24 South Africa Egypt Mmabatho Stadium North West 11. 1995.12.15 South Africa Germany Johannesburg Athletics Stadium Gauteng 12. 1996.01.13 South Africa Cameroon Soccer City Gauteng 13. 1996.01.20 South Africa Angola Soccer City Gauteng 14. 1996.01.24 South Africa Egypt Soccer City Gauteng 15. 1996.01.27 South Africa Algeria Soccer City Gauteng 16. 1996.01.31 South Africa Ghana Soccer City Gauteng 17. 1996.02.03 South Africa Tunisia Soccer City Gauteng 18. 1996.04.24 South Africa Brazil Soccer City Gauteng 19. 1996.06.15 South Africa Malawi Soccer City Gauteng 20. 1996.09.14 South Africa Kenya King's Park KwaZulu-Natal 21. 1996.09.18 South Africa Australia Johannesburg Athletics Stadium Gauteng 22. 1996.09.21 South Africa Ghana Loftus Versfeld Gauteng 23. 1996.11.09 South Africa Zaire Soccer City Gauteng 24. 1997.06.04 South Africa Netherlands Soccer City Gauteng 25. 1997.06.08 South Africa Zambia Soccer City Gauteng 26. -

Grassroots, Vol. 9, No. 1

Grassroots, Vol. 9, No. 1 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 23 Alternative title Grassroots Author/Creator Grassroots Publications (Cape Town) Publisher Grassroots Publications (Cape Town) Date 1988-02 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1988 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Format extent 8 page(s) (length/size) Page 2 of 23 NON - PROFIT COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERgrassrootsTHE PAPER ABOUT YOU VOL. 9 NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1988 FREEANCCALLSFORUNITYTHE disunite that the apartheid regime generateamongst the oppressed people ensures that it gains alonger lease of life, the African National Congresssaid in a statement from Lusaka earlier this month.Responding to events in KTC, the ANC made aspecial appeal to the militant youth to "take the leadin ensuring that all hostilities amongst our peoplecease at once".The ANC further said: "It is against the colonialapartheid regime that we should direct our anger andaim our blows. -

SY3057 Football and Society | Readinglists@Leicester

09/30/21 SY3057 Football and Society | readinglists@leicester SY3057 Football and Society View Online 1. Lewis, R. W. Innovation not Invention: A Reply to Peter Swain Regarding the Professionalization of Association Football in England and its Diffusion. Sport in History 30, 475–488 (2010). 2. Allison, Lincoln. Association Football and the Urban Ethos. Stanford Journal of International Studies (1978). 3. Bailey, S. Living Sports History: Football at Winchester, Eton and Harrow. The Sports Historian 15, 34–53 (1995). 4. Baker, N. Whose Hegemony? The Origins of the Amateur Ethos in Nineteenth Century English Society. Sport in History 24, 1–16 (2004). 5. Dunning, E. Sport matters: sociological studies of sport, violence, and civilization. (Routledge, 2001). 6. Dunning, E. & Sheard, K. G. Barbarians, gentlemen and players: a sociological study of the 1/42 09/30/21 SY3057 Football and Society | readinglists@leicester development of rugby football. (Frank Cass, 2005). 7. Garnham, N. Patronage, Politics and the Modernization of Leisure in Northern England: the case of Alnwick’s Shrove Tuesday football match. The English Historical Review 117, 1228–1246 (2002). 8. Giulianotti, R. Football: a sociology of the global game. (Polity Press, 1999). 9. Harvey, A. Football: the first hundred years : the untold story. vol. Sport in the global society (Routledge, 2005). 10. Holt, R. Sport and the British: a modern history. vol. Oxford studies in social history (Clarendon Press, 1989). 11. Hutchinson, J. Sport, Education and Philanthropy in Nineteenth-century Edinburgh: The Emergence of Modern Forms of Football. Sport in History 28, 547–565 (2008). 12. Kitching, G. ‘From Time Immemorial’: The Alnwick Shrovetide Football Match and the Continuous Remaking of Tradition 1828–1890. -

Payment Form Attached and Return It to the Office Or by Mail ( [email protected] ) Before the 12Th of June

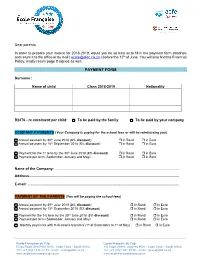

Dear parents, In order to prepare your invoice for 2018-2019, would you be so kind as to fill in the payment form attached and return it to the office or by mail ( [email protected] ) before the 12th of June. You will also find the Financial Policy, kindly return page 8 signed as well. PAYMENT FORM Surname : Name of child Class 2018-2019 Nationality R2376 - re enrolment per child: To be paid by the family To be paid by your company COMPANY PAYMENTS (Your Company is paying for the school fees or will be reimbursing you) Annual payment by 30th June 2018 (8% discount) in Rand in Euro Annual payment by 15th September 2018 (5% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment for the 1st term by the 30th June 2018 (3% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment per term (September, January and May) in Rand in Euro Name of the Company: ............................................................................................................................ Address...................................................................................................................................................... E-mail: ....................................................................................................................................................... PAYMENT BY THE PARENTS (You will be paying the school fees) Annual payment by 30th June 2018 (8% discount) in Rand in Euro Annual payment by 15th September 2018 (5% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment for the 1st term by the 30th June 2018 (3% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment per -

Analysing Rugby Game Attendance at Selected Smaller Unions in South Africa

Analysing rugby game attendance at selected smaller unions in South Africa by PAUL HEYNS 12527521 B.Com (Hons), NGOS Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Business Administration at the Potchefstroom Business School of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof. R.A. Lotriet November 2012 Potchefstroom ABSTRACT Rugby union is being viewed and played by millions of people across the world. It is one of the fastest growing sport codes internationally and with more countries emerging and playing international and national games, the supporter attendance is crucial to the game. The rugby industry is mostly formal, with an international body controlling the sport globally and a governing body in each country to regulate the sport in terms of rules and regulations. These bodies must adhere to the international body’s vision and mission to grow the sport and to steer it in the correct direction. This study focuses on rugby game attendance of selected smaller unions in South Africa. Valuable information was gathered describing the socio- economic profile and various preferences and habits of supporters attending rugby games. This information forms the basis for future studies to honour the people that support their unions when playing rugby nationally or internationally. The research was conducted through interviews with influential administrators within the rugby environment and questionnaires that were distributed among supporters that attended a Leopard and Puma game. The main conclusions during the study were the failure to attract supporters to the Leopards and the Pumas local matches. The supporters list various reasons for poor supporter attendances namely: a lack of marketing, no entertainment, the quality of the teams that are competing, and the time-slots in which the matches take place.